Film Room: Breaking down Russell Wilson and the Seahawks' passing game

It was fitting that the Seattle Seahawks won the NFC Championship on a play of more than 20 yards. It's what they've done all season.

In 2014, they racked up 54 passing plays of 20 or more yards, tied for 11th-most. So it wasn't shocking when defending Super Bowl champion quarterback Russell Wilson checked to a skinny post route against Cover 0 and found wide receiver Jermaine Kearse in the end zone for the game-winning, 36-yard score.

Now they have to do it again. This time, it'll be against the New England Patriots' revamped secondary in Super Bowl 49.

The Patriots' defense has had issues with playing deep throws for years now. Their linebackers and cornerbacks have struggled, at times, to run with running backs and receivers and track deep throws. They allowed 62 passing plays of 20 or more yards in 2014, seven more than the previous season. And they didn't have Darrelle Revis nor Brandon Browner then.

Both defenders and their teammates could find themselves grabbing and pulling the Seahawks' skill players downfield in order to catch up. The Seahawks' receivers aren't an overly skilled or special group, but they're quick and run crisp routes. Their running backs - specifically Marshawn Lynch - are underrated route runners who run with timely bursts and aggressively turn corners.

With that, here are X-factors in the Seahawks' passing game that could threaten the structure of the Patriots' pass coverage.

See 'Spot' Run

Before the NFC Championship, Lynch had caught one wheel route all season. He wasn't a downfield threat and served better as an outlet receiver for Wilson.

When Wilson scrambled or struggled to navigate the pocket, Lynch was there. He racked up more than three dozen receptions, including five of 20 or more yards, and career-highs of four touchdowns and 367 yards.

That's why it was a surprise when the Seahawks not only sent Lynch on a wheel route once in their miraculous win against the Green Bay Packers, but twice.

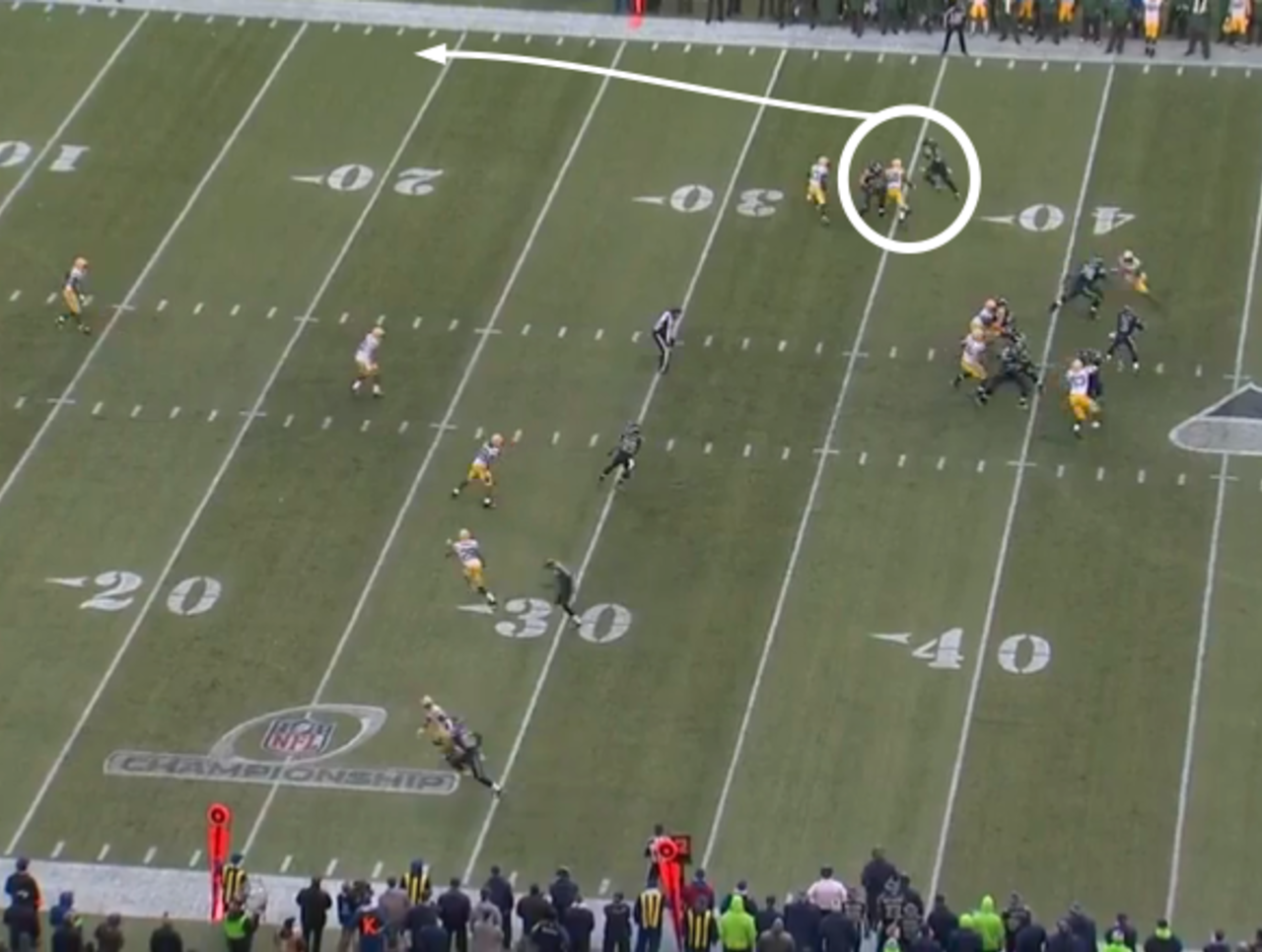

The first time was late in the third quarter. Lynch weaved out of the backfield, curved outside the numbers and … juggled the ball five yards shy of the end zone before a Packers linebacker ripped it out of his hands. Despite the drop, there was potential.

Potential meant a chance, an opportunity for the Seahawks to hit on the pass and electrify their offense. It had struggled throughout the game until second-and-10 late in the fourth quarter. The concept was the same, which started with the tight end running a spot route to pick off the near defenders. One of them was an inside linebacker.

The linebacker, who had worked over the top of the spot route in the third quarter to break up the pass to Lynch, went underneath the spot route this time. Foolish. That freed Lynch to beeline outside the tight end's route and the numbers, past the jammed up inside linebacker, past the cornerback who had his back turned, and ensnare the football over his shoulder for a 26-yard catch.

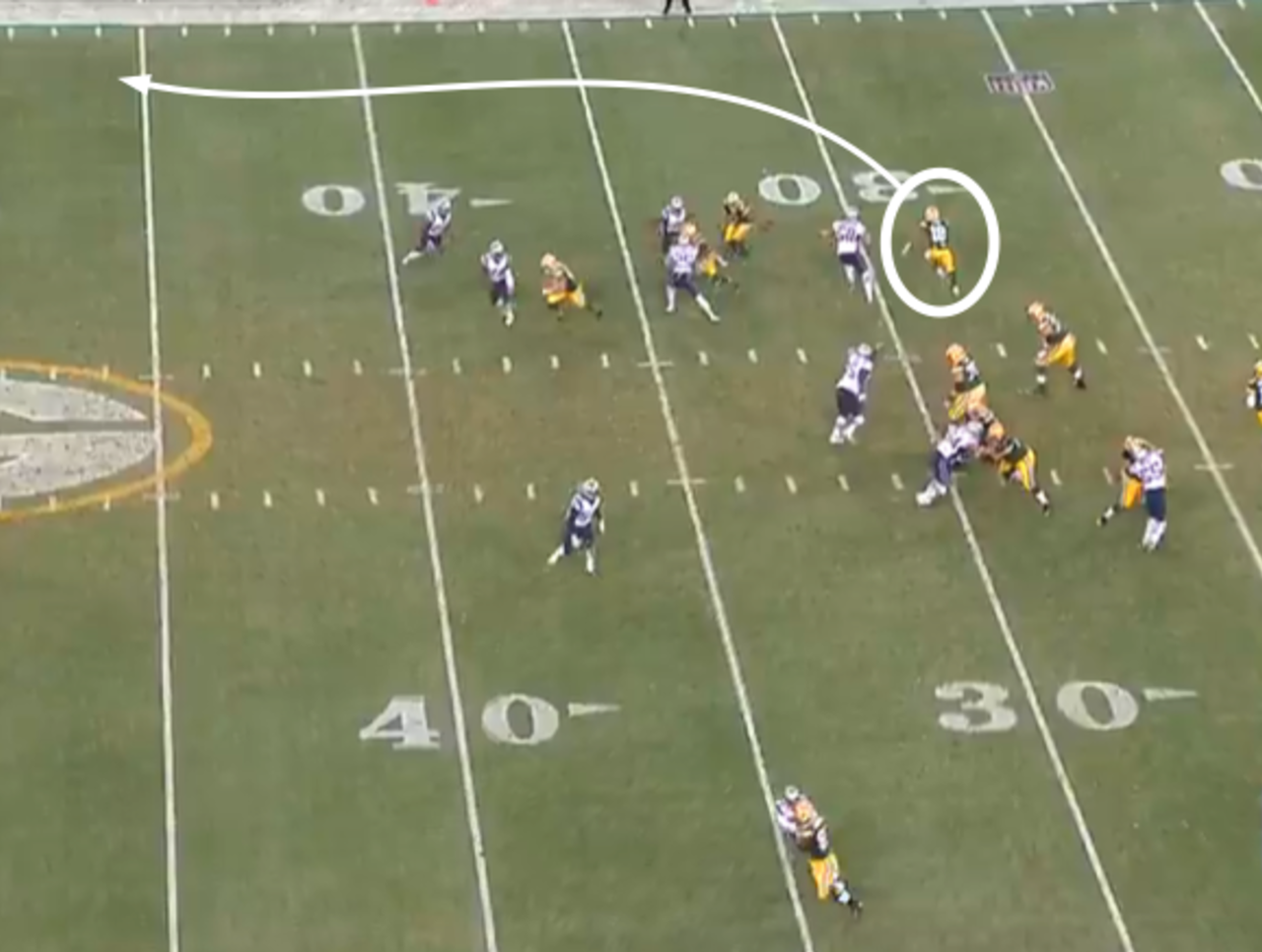

When Lynch runs out of the backfield in the Super Bowl, he may see an inside linebacker or a nickel cornerback. The Patriots have used either to run with running backs (and receivers) out of the backfield, sometimes without success. Here's an example from Week 13 against the Packers.

In the second quarter, it was third-and-5 when receiver Randall Cobb hustled past a trio of pass catchers and whipped outside the numbers. One of the pass catchers ran a slant route and jammed the nickel cornerback, which forced the outside linebacker to convert his rush to coverage.

That created a speed mismatch in favor of the Packers. Quarterback Aaron Rodgers lobbed a 33-yard pass down the ride sideline to Cobb.

The Seahawks may look to exploit the Patriots in the same way. They saw a mismatch against the Packers, who didn't always find their way through the picks, and used it in their favor. Now that leaves the Patriots to ponder how to stop Lynch, both in the passing and running games.

Spacing with 'Bunch' and 'Nub' Sets

Another X-factor in this Super Bowl will be the Seahawks' sets. Like any other good offense, they use their bunch and nub sets to create favorable matchups in the passing game.

The bunch set is when two eligible pass catchers are in reduced splits together. They may be side-by-side, with one on the line of scrimmage and another off it. The receiver on the line is the point-man, who often faces bump-and-run coverage.

The nub set, in contrast, is when a tight end is the only eligible pass catcher on one side of a formation. In other words, there are no complementary receivers to the outside.

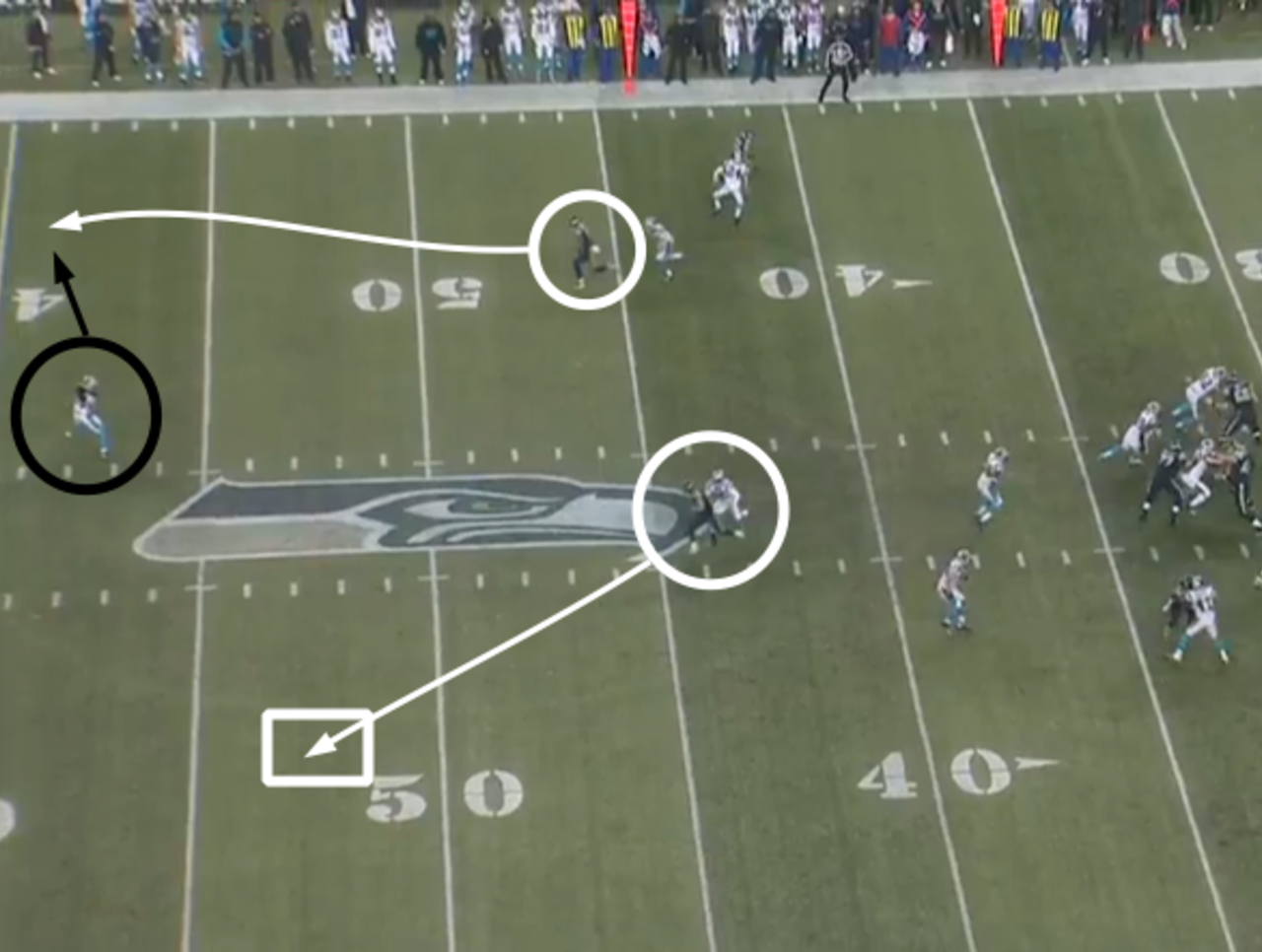

Against the Carolina Panthers in the Divisional Round, the Seahawks faced third-and-7 when they lined up with a nub to the left side and a trips set to their right. The Panthers walked their strong safety over the tight end, who stayed in to block at the snap, rendering the safety useless in coverage.

With the strong safety stuck in the trenches, the Seahawks' No. 2 receiver zoomed downfield on a go-route while the No. 3 receiver crossed to the deep half of the field. That forced the free safety to decide who to cover.

Once the free safety widened his hips toward the No. 2 receiver, Wilson shifted his eyes left to the No. 3 receiver and struck with a 63-yard bomb.

The Patriots' defense has faced both nub and bunch sets before - on the same play. Once, in the Divisional Round, the Baltimore Ravens lined up with a solo tight end to the left. To the right, two receivers were bunched.

The tight end beat the jam and ran toward the left sideline, trailed by the strong safety. That left the Patriots with one deep safety, Devin McCourty.

Containing Russell Wilson

As long as the Seahawks' passing game is structured, the Patriots can defend it. It's when Wilson roams that makes it difficult.

The Packers had confined Wilson to the pocket for three-and-a-half quarters in the NFC Championship before Wilson was loosed and flipped the game upside down. Their defensive ends and linebackers had stayed outside while the interior rushers penetrated inside. They punched the Seahawks' patched-up offensive line and punished Wilson with five sacks. Yet, by the end of the fourth quarter, he scrambled for 15 yards on one play and bustled for another on a one-yard touchdown to swing his team back into the game.

Whether Wilson is rolling out of the pocket or flushing it by force, he eyes open receivers, who also have a knack for breaking off their routes or tagging them to find soft spots against coverage.

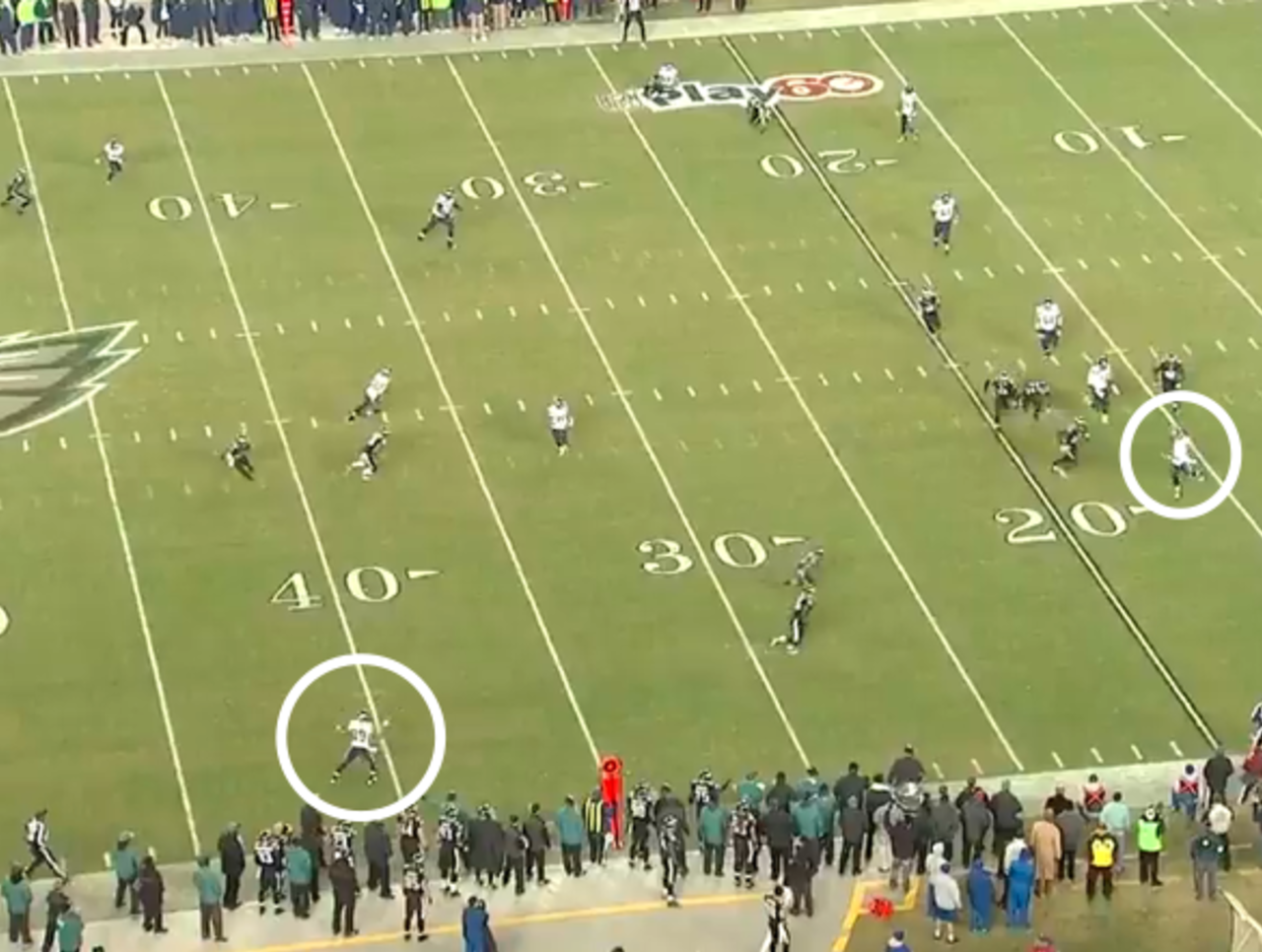

In Week 14, Wilson caught a second-and-10 shotgun snap and dropped back three steps. He looked to his left and pump-faked to a shallow crosser, making two Philadelphia Eagles defenders lurk over the crosser and force Wilson to look right.

There, to his right, Lynch leaked out of the backfield on a screen pass, but the Eagles hurried to that, too. The play seemed dead … until Wilson looked back left and scrambled.

The Eagles' rush had been disciplined to that point and hadn't fell for the baiting blocks of the Seahawks' linemen. They abruptly crumbled. The four-technique end who contained the outside found himself inside the backfield dancing with Wilson.

Wilson weaved outside and inside and then outside, broke the pocket and rushed to his left. The end fell. Wilson was free. He rolled left and looked at the two Eagles defenders that had erased the shallow crosser. They stood and stared at him.

Meanwhile, the shallow crosser ran by both Eagles defenders to the sideline and found a nook. The rest of the Eagles' defense flowed toward Wilson like a brook. Wilson kept his eyes up, though, and lofted a pass into the shallow crosser's hands for a 25-yard gain.

It's not a question of if; it's when. When will Wilson escape? He's going to escape. He always does. He constructs new offenses and deconstructs old defenses. Then he drops a deadly dagger like it's straight from the sky.

The Patriots, too, will find this out at some point. They haven't faced a quarterback like Wilson this season. A quarterback who entangles the shape of their defense. A quarterback who - according to Bill Belichick - is reminiscent of two-time Super Bowl champion with the Dallas Cowboys, quarterback Roger Staubach.