Unique Team Traits: The Buffalo Sabres and the remarkably feeble power play

theScore’s multi-part team previews includes a look at something that separates each team from the pack. From specific breakouts to powerplay formations and beyond, Justin Bourne and Thomas Drance hope to highlight something you haven’t noticed in the past.

What we noticed

The Sabres’ powerplay was an atrocity

The Buffalo Sabres powerplay was bad. You can go to the thesaurus and get some better words for “bad,” but at its core, that’s what it was. Bad.

There’s a laundry list of reasons, given that they basically did nothing well with the man advantage, but in the big picture, they struggled to get set up, they were frenzied when they did (oh, were they frenzied), and they couldn’t get the puck to the net.

The reality is that they just didn’t have the horses, and Ted Nolan did them no favors.

The numbers

The only thing that saved the Buffalo Sabres from having the worst powerplay in the NHL was the Florida Panthers trotting out the most useless powerplay the NHL has seen since 2000-01. The Sabres converted on 14.1 percent of their opportunities, which saw roughly zero players hit 20 powerplay points on the year. (If a Sabre had a scoring chance, there was little incentive to not just hook him around the neck.)

They were remarkably feeble when up two men. They scored zero goals at 5-on-3 on the year (10 tries), chalking up a shots-for-per-60 mins in that situation of 32. As in, if they played an hour of 5-on-3 hockey, they were on pace to get a shot every two minutes. For context, the then-Phoenix Coyotes - the league’s best 5-on-3 team by shot rate - were on pace for about 150.

The plan behind the futility

The Sabres generally rolled out some combination of Cody Hodgson, Tyler Ennis, Drew Stafford, Steve Ott, Christian Erhoff and Tyler Myers. (When they no longer had Matt Moulson or Thomas Vanek, things got really bleak.) So for starters, you’re not working with the Flyers personnel; as a result, they had some struggles.

When I mentioned that Ted Nolan isn’t helping them, it’s because he took middling NHL talent, and stuck them around the perimeter of the zone in the world’s most generic set-up: the overload.

In the basic overload, the guy on the half-wall and the low forward are interchangeable. They do a lot of pass and rolls - as in, move the puck from the wall to the goal line, switch spots, and … hope for something to open up?

The idea is that the guy in front is an option for a pass from the half-wall, and he’s a one-timer option from the low spot. If the puck goes high, he can screen and tip (in which case the low forward would go rebound hunting). He’s integral to the whole thing. Also, teams know he’s integral to the whole thing, so they take him away - there’s really no other danger to cover - so your PP is immediately stagnant.

The low forward has the option to take the puck to the net, but he’s usually strung so far out wide that’s it’s not really a reasonable option. The guy on the half-wall can shoot, but you’ll give up that harmless shot up all day. The D-man is on the boards is providing the half-wall QB an option, so he’s in the least dangerous shooting position on the ice. And the other D-man can either take a one-timer, or give the puck back because he has no option on his left side.

If you can’t tell, I do not care for the basic overload. You just end up over-passing the puck around the perimeter until two minutes is up.

The breakdown

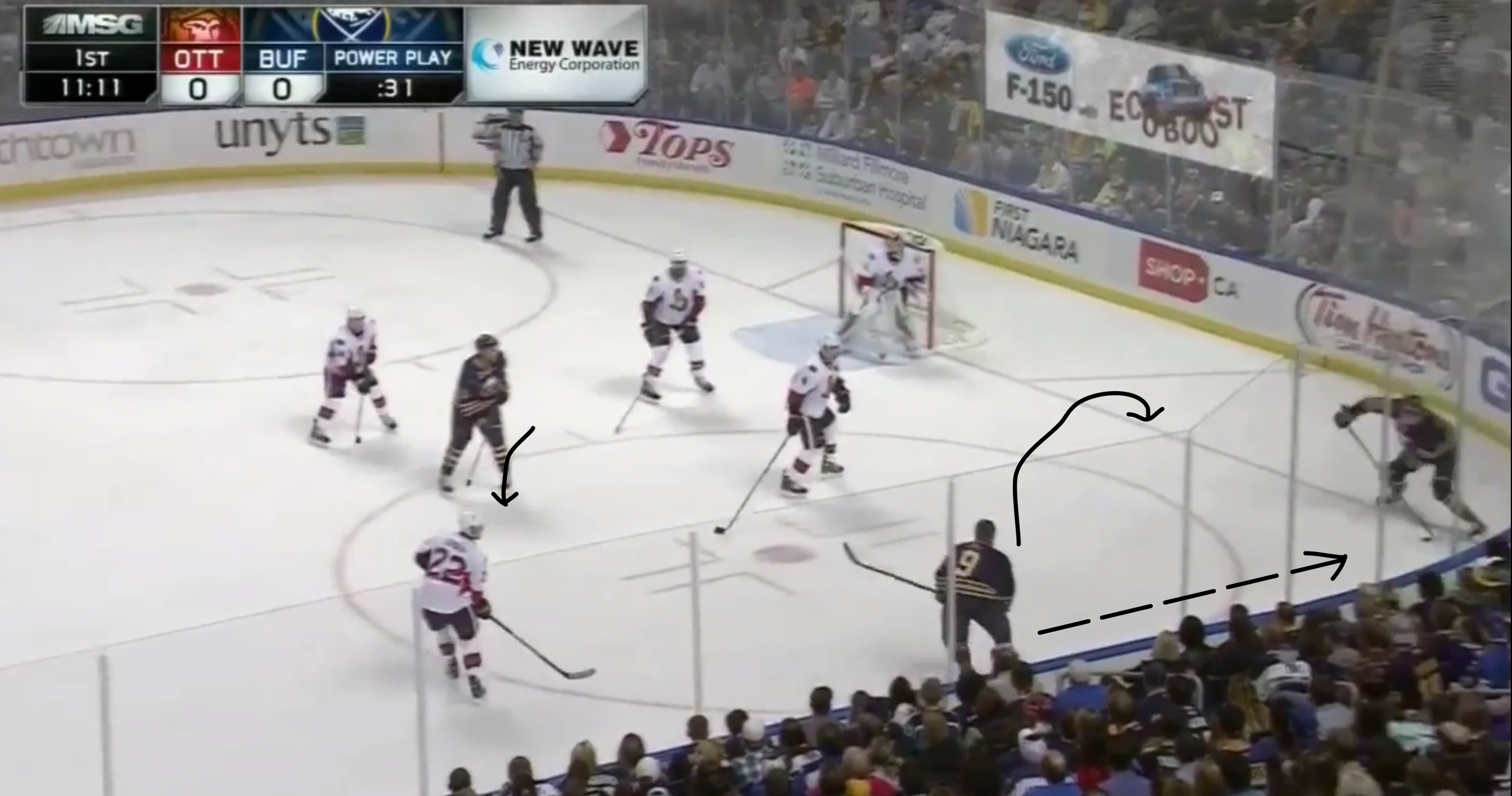

Here’s Steve Ott on the half-wall - he’s interchangeable with Cody Hodgson who’s low. (Hodgson generally starts on the boards.)

So Ott’s got two options, realistically. He rolls it low.

He goes to take Hodgson’s spot, who now has the puck. The man in the high slot is covered by pretty much everyone. The penalty killers are happy to have them play around out there.

Hodgson does a really, really good job passing the puck as soon as he gets it, and not skating up then passing. Let the puck do the work. There’s no need to skate to the guy you’re giving it to.

Mark Pysyk (I know, I know, let’s just move on) moves the puck across to his partner, who uses one of his two options, and shoots. (An unscreened shot he pulls wide.)

And now you’re puck hunting again.

The overload is entirely ineffective unless the wall and low forwards threaten the box, which the Sabres rarely did. There has to be some attempts to attack, otherwise nobody ever gets pulled out of position, and nobody’s open.