My week at umpire school, where everyone wants a thankless job

Warning: Story contains coarse language

I'm blowing it.

I can sense Dana DeMuth's disappointment, and there's nothing worse than disappointing Dana DeMuth, whose 35-year tenure as a big-league umpire earned him the dubious privilege of helming this cage session. I can't really see his disappointment, though, because my grossly oversized umpire's mask keeps nudging my glasses further and further down the bridge of my nose.

Not being able to see also makes it difficult to determine whether a pitch is a ball or strike. And, as I've learned in the last few days, that's already pretty damn hard.

While DeMuth bombards me with constructive criticism, I feel like I'm exemplifying a maxim I've heard countless times since arriving at the Wendelstedt Umpire School. On my first day, 21-year major-league veteran Hunter Wendelstedt quoted the line, making sure to attribute it to Harry, his venerated late father.

"You can't hide a good umpire and you can't hide a bad umpire," he said.

I'd been exposed. Then again, as a baseball writer who dropped in 10 days after the course started, I was never going to be able to hide.

__________

The Wendelstedt Umpire School is one of two academies with a curriculum approved by Minor League Baseball for professional development. Each year, the school enrolls about 100-150 students, most of whom register for the intensive five-week program hoping to make umpiring their career. Only the top 15-20 percent will be hired out of school into the minor leagues, where they'll begin an arduous, thankless, and often fruitless trek to the majors.

"We get so many great umpires - and they would be great candidates for Major League Baseball down the road, we think," said chief field instructor Jansen Visconti. "But they get out there and they experience what it's like to drive 12 hours after working a game and then get in at 8 in the morning, and you're waking up at 4, and your sleep pattern is all screwed up, and you're away from home and away from the kids, and you're missing Fourth of July picnics or Memorial Day picnics or whatever it may be - that's tough.

"And there's a lot of guys that just can't do it. It's too much for them," continued Visconti, who made his big-league debut in 2018 - his ninth season as a professional umpire. "That's why the drive and the passion, it has to be there ... and you have to enjoy coming to work every day."

Maybe one student from this year's intimate class of 89 will ever work a game in the bigs. The roster of major-league umpires features fewer than 100 names, including the taxi-squad fill-ins summoned from Triple-A when a full-timer gets hurt or goes on vacation, and the turnover rate is incredibly low.

"You can go to med school and law school in the same amount of time it takes it to progress through the minor leagues and get that opportunity to be a major-league umpire," Hunter Wendelstedt noted.

Visconti said, "We try to make them aware of what the statistics are. Every single one of us instructors understands the process to be a major-league umpire. It's demanding. It's grueling. Lots of sacrifices made."

I, for one, am not willing to make those sacrifices. I already have a career, but even if I didn't, I don't know that I'd be down to spend my next 10 summers driving from one podunk town to another, making peanuts to chase down an improbable payoff. I love baseball more than I could ever love a human baby, but that's a grind. I'm not crazy about having to shave every day, either, never mind the idea of wearing long sleeves for a July matinee in the Carolina League just to cover up my tattoos.

Nevertheless, they welcomed me with open arms at the Wendelstedt Umpire School, where I briefly embedded myself in January in order to find out how these aspirants - in pursuit of a career that would at best render them invisible or despised - are transformed into professionals. Nobody considers umpires until they're enraged at them, usually. But without them, baseball doesn't happen, and I wanted to see how the sausage gets made. I also wanted to see if I, a professional Baseball Knower, could waltz in late and still hold my own.

For the better part of a week, I lived, studied, and worked among the students in Ormond Beach, Fla., just north of Daytona, going through the paces like I had paid the $2,450 tuition fee. (I hadn't; the academy graciously accommodated me at no charge.) And this is how baseball's most prolific umpire school turns its cadets - some of whom show up without having umpired a single inning - into the stoic stewards you berate from your couch from April through October.

__________

School runs Monday through Saturday, and most days begin in the classroom, starting with roll call promptly at 9 a.m. For two-and-a-half hours or so each morning, a pair of instructors - one reading from the rule book, another interpreting - pore over the minutiae of obstruction and offensive interference and every other arcane rule you thought you knew, using visual aids and clips from MLB games to help translate the dizzying language of a rule book essentially written in legalese. Here, for instance, is Rule 6.01(a)(10) on interference:

It is interference by a batter or runner when:

He fails to avoid a fielder who is attempting to field a batted ball, or intentionally interferes with a thrown ball, provided that if two or more fielders attempt to field a batted ball, and the runner comes in contact with one or more of them, the umpire shall determine which fielder is entitled to the benefit of the rule, and shall not declare the runner out for coming in contact with a fielder other than the one the umpire determines to be entitled to field such a ball.

That rule has 10 other subsections.

It is tedious and necessary, the class work. (Admittedly, the lecture on "handling situations," umpire parlance for ejections, was rather spirited.) The other instructors, all of them either minor-league or major-league umpires, help enliven the lectures with relevant tales from the road. Students - most of whom take diligent notes, or at least snap photos of the lecture slides on their phones - pay particularly close attention when a big-league veteran like Ed Hickox or DeMuth chimes in with an anecdote or insight.

If anyone can make the subject of obstruction interesting and accessible, it's DeMuth, who famously ended Game 3 of the 2013 World Series when he invoked the rule on Boston Red Sox third baseman Will Middlebrooks. "I was praying (third base umpire) Jimmy (Joyce) would call it," he recounted, having taken charge of that particular lecture. Sadly, neither Hickox or DeMuth was called on to spruce up our discussion of "Ball Hits a Runner's Dislodged Helmet."

Most umpires won't apply half the things they learn in class, but that doesn't matter. Knowing the rules is paramount (and ideally, students would memorize rulebook terminology verbatim). They're all rooted in common sense and fair play, a point the instructors frequently belabor, but umpires need to know what do to on freak plays with freak rulings that defy those principles. Errors in judgment are part of the job. Not knowing - or misapplying - a rule will end your career.

To that end, the students are quizzed often, writing 25 tests comprised primarily of multiple choice and true-or-false questions over five weeks. To qualify for advancement, students must achieve a 70 percent average.

My first day in class, we were being tested on the infield fly rule. (Beforehand, two students debated whether "routine" or "ordinary" effort was required on the part of the infielder.) The instructors were reluctant to hand me a test, but I insisted. I got 8 of the 10 questions correct. Then we were handed another test, this time on the awards conferred to baserunners on balls thrown or deflected out of play. This was one of two questions I botched:

What is the proper ruling for base runners, if, after catching a pop fly over foul territory, the fielder steps into the dugout but remains standing?

A) The BR is out, the ball is dead, and each runner is awarded one base;

B) The BR is out, the ball is dead, and each runner is awarded two bases;

C) The BR is out, the ball is alive and in play, and runners may advance at their own peril.

Still, I surmised, if being a professional umpire required no actual umpiring, I'd be at Yankee Stadium tomorrow. (The correct answer is A, for the record.)

__________

The ideal student, according to Wendelstedt, has no qualifications beyond a passion for baseball, and that may be the only trait shared by each member of the student body.

Frustrated ex-ballplayers from the American Midwest and South - desperate to stay in the game - provide a critical mass, but this year's class is far from homogenous. Students came from as far as Japan and the Dominican Republic. Some can't legally buy a drink in the United States until 2021, while others lived through the Truman administration. And a love for baseball brought them all here, be it the corrections officer from Scranton or the serviceman-turned-EMT-turned-TBD from Hawaii.

Pragmatism was as compelling a force as passion for Cory Takeshita, an undersized cadet with a wispy mustache who studied marine ecology at Long Beach State. He opted to take a crack at professional umpiring on account of "the political climate" under President Donald Trump.

"He is very against the sciences and it's not very beneficial for me to go into a field where there are less jobs available for college graduates coming out and trying to directly go into that field," said Takeshita, who loaned me his windbreaker on my first day at school.

A grant system already renders all researchers essentially contract workers, Takeshita explained, adding that it's not uncommon in his field to be out of work for extended periods. Umpiring, he suggested, is far less precarious.

"It's fun. It keeps you on your toes all the time. It's outdoors. But it's a job in which, no matter what happens, it's always going to be here," said Takeshita. "As long as there's sports, there's always going to be a need for officials and referees and that kind of stuff.

"It's a very stable job if you think about it."

__________

Class usually adjourns just before noon, at which point students meander to the baseball diamonds down the road. Twice a day, they line up in the outfield for formation, in which they work on their umpiring mechanics - strike calls on a right-handed batter, ball calls on a left-handed batter, out, safe, time - and try to avoid the wrath of the exercise's bullhorn-wielding instructor. Never is the sense of fraternity in camp more palpable than when all 89 students scream "He's out!" in unison, their accompanying right-hand signals perfectly in sync.

After formation, the students hustle to the cages or their assigned field for drills and, later, simulated games. For me, this is where the fear really starts to kick in: We have to actually do stuff.

On my first day, the focus is awarding bases for balls thrown out of the play, and it all seems very clear as I watch the drill unfold over and over while awaiting my turn as base umpire.

Runner on first and the batter grounds a potential double-play ball to shortstop? Move into the working area (the space behind the pitcher's mound), stepping first with right foot and pivoting to stay square to the baseball; follow the throw and get into the set position (feet just over shoulder-width apart, hands on knees); make a call, then drop-step, if necessary, with the right foot to follow a possible throw to first; make a call on the batter-runner. The entire ballet is but a few simple steps. Then it's my turn, and I jog out to the middle of the diamond.

When the instructor cracks a grounder to short, I essentially black out. The runner on first breaks for second. I square up to the baseball like I'm supposed to, but I err in assuming the set position as the shortstop corrals the grounder and flips it to the bag, precipitating some hilariously inelegant footwork as I make the call ("Out!") on the play at second, then track the overthrown ball to first. I've seen the drill enough times to know that a ball tossed into the stands on the second play by an infielder results in two bases for each runner, including the batter-runner, from the time of the throw, which means I have to make another call.

"YOU!" I scream, pointing at the batter-runner and signalling him along. "SECOND BASE!"

Having made the correct call, and with a shocking level of authoritativeness, I proudly rejoin my base-umpire cronies. They welcome me with first bumps and pats on the back, and I'm immediately overtaken by a sense of camaraderie. Even though they're technically competing against one another - one student described the course as a "five-week job interview" - they're pulling for one another. One play in, I feel like I belong.

But in this instance, I know - or at least have a pretty good idea - where the ball is going. That isn't the case in control games: The base-out situation changes with each play, and the umpires must respond to whatever arises.

The intensity picks up dramatically, and instructors dispense with the niceties. When one of the more promising students defended his non-call on a potential infield fly, the drill instructor deemed his interpretation of the play "horseshit." When another student called time at the conclusion of a play in which the "pitcher" got smoked in the foot by a line drive, he was chastised: "We're not going to call time to see if the pitcher's OK. Fuck him."

Correct calls made emphatically elicit cheers from those awaiting their turns. Calls meekly made earn rebukes from the instructors. Selling the call is just as important as getting it correct. Often, it doesn't matter if you're right or wrong so long as you're loud enough.

The instructors didn't test me much in control games, primarily running straightforward plays that didn't force me - as the plate umpire - to consider, say, both catcher's interference and a potential fair-or-foul call. To a degree, I appreciated it. Removing my mask without also yanking my hat off was difficult enough.

__________

Few students, if any, arrive for class before Greta Langhenry, who always chooses the seat on the inside aisle of her row, closest to the instructor. She signed up with no prior umpiring experience, and learning the two-man system that's standard in the lower levels of the minor leagues has been "a real challenge."

Being the lone woman in class, however, has been surprisingly easy.

"I've been super lucky," said Langhenry, 31. "I've talked to some women who've played baseball and umpired - and women who work in other male-dominated areas - who were worried for me or wanted me to know I could talk to them, (but) everybody here from the students to the instructors have been super nice to me. I feel like one of the guys."

She continued: "If you're a good umpire, your partner doesn't care if you're a man or a woman or whatever."

Baseball, as an institution, hasn't historically been very welcoming to women umpires. Pam Postema attended the academy four decades ago (when it was still named after Al Somers) and later become the first woman to umpire a major-league spring training game. Her contract wasn't renewed when she was on the doorstep of the big leagues in 1989. "If I'm not good enough to make it as an umpire," she told the New York Times, "there'll never be a woman who can make it." Ria Cortesio was released in 2007 after nine years in the minors. Like Postema, she'd also called an MLB spring-training game. She decried baseball's working environment for women as "horrendous" and described a "systematic targeting of women."

Langhenry was "a little nervous" about enrolling, but some research allayed her fears.

"I pulled up some YouTube videos," Langhenry said, "and in one of them Hunter Wendelstedt talks about the school ... and actually says in the video he'd like (for his academy) to be the school that puts the first woman into the major leagues. So I thought, 'All right, they're going to be friendly and I should try before I'm too old.'"

And they were, she said, making it that much easier to focus, learn, and ultimately distinguish herself on the basis of her ability.

"People say, 'Oh, you could be the first.' For me, I don't really care about being the first," said Langhenry. "I'd like to make it to professional baseball, and then I'd like to be the best. I would like, eventually, for it to not matter that I'm a woman. I'd like them to just say, 'She's really good.'"

__________

Umpires make their money at home plate, the saying goes, and that's probably why cage work - calling balls and strikes off a pitching machine - is the only exercise helmed at all times by a major-league veteran. Personally, I find the intimacy of the cage terrifying, and the exercise precipitated a much more potent brand of anxiety than the control games and drills.

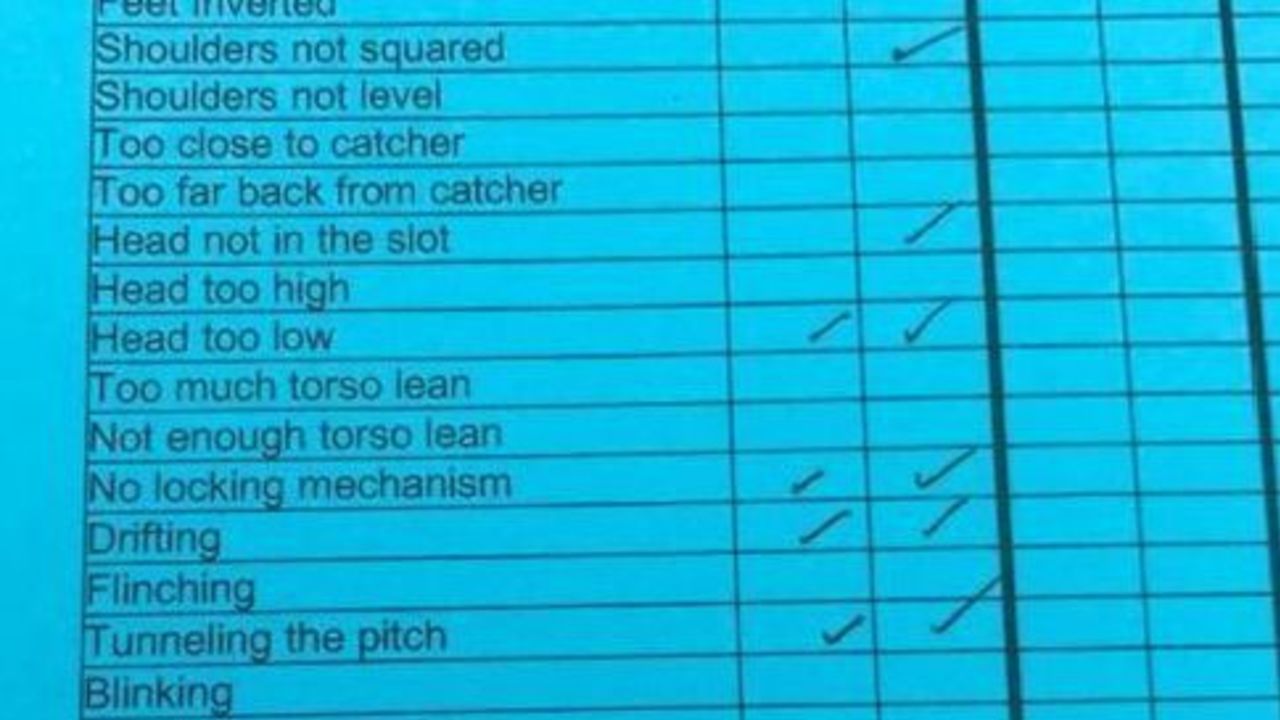

Each umpire, in full gear, tracks eight low-velocity pitches from the machine with a right-handed "batter" (an umpire holding a plastic bat) at the plate under the tutelage of Hickox or DeMuth. Another instructor marks "areas of deficiency" on a blue progress card. After eight pitches, the batter hops over to the opposite batter's box for another eight. On the final pitch, regardless of location, umpires are asked to uncork their strike-three call - the punchout, one of the few calls they're at liberty to stylize.

A couple of weeks into camp, having repeated their mechanics ad nauseam, my peers in the cage seemed relatively comfortable behind the plate. I, conversely, was not, and I got off to an inauspicious start; I took an inordinate amount of time gearing up, and I dropped my ball-strike indicator on my way into the cage.

Hickox was quite measured and restrained in his feedback for my fellow group members. With me, he was too, but my report card indicated that he could've torn me a new one: my shoulders weren't square; I rushed my calls; I failed to "lock" (protect) my outside arm; my vocal mechanics were unsatisfactory; my signals weren't assertive. As my final pitch loomed, I knew I had to redeem myself with my strike-three call. Hickox nodded at the feeder. The pitching machine spat out a belt-high offering, right down the middle. In one elegant move, I drop-stepped with my right foot and yanked the cord on an imaginary snowblower with my right arm.

"HAAAA! THREEE!" I bellowed, impossibly self-satisfied.

"That was up, wasn't it?" Hickox deadpanned.

"I had it at the belt."

He chuckled and patted me on the back. I had survived. Barely.

My next - and final - cage session two days later was worse, and not just because my glasses kept getting crushed by my face mask (I'd worn contacts the first time). My footwork and positioning were atrocious - I consistently squared to first base instead of the pitcher. I flinched at one pitch and, in my haste to signal strike or ball, repeatedly failed to track the baseball all the way into the catcher's glove.

About 30 seconds into my session, DeMuth, a tenacious instructor with an inexhaustible reserve of patience, quipped: "You haven't umpired before, have you?" (I had umpired before, as a teenager; the 7-year-olds in the Thornhill Baseball Association are somewhat less discerning than the instructors at the Wendelstedt School.)

I tried to be as responsive as possible to DeMuth's instruction, but my glasses were a constant distraction. I couldn't ever seem to get into the optimal position, either because I was setting up too close to the catcher, or my feet were askew, or my crouch was too low. My peers' amused chuckles quickly dissipated.

After an eternity, the dude feeding the pitching machine called out, "Last pitch." It was time for my punchout.

From what I considered to be a place of genuine pity, DeMuth asked, "Do you want a strike-three call?"

"You better believe it," I bravely responded.

At the risk of discrediting myself, I don't have the words to express the relief I felt taking off my shin guards and chest protector moments later.

__________

Nearly a decade removed from a stroke that he says killed him twice, Chad Bush doesn't get around the diamond particularly well. His unmoving left arm, tucked up against his belly or side, is a permanent reminder of the "hell on earth" he endured in 2010. He has no illusions about umpiring in the big leagues. But if he can teach himself how to walk, talk, and eat again, he figures he can still umpire at the college level even with his physical limitations - a notion that led the 44-year-old to save up the money he earned umpiring last summer to attend the Wendelstedt School.

"I had trouble catching up to these fast kids," Bush said in a thick New England accent. "So here they're showing you how to gain steps with footwork and pivots, drop-steps to gain the distance and angle you need to get ahead of these fast runners and stay ahead of them. After a stroke, I need all the help I can get."

Bush, who worked for Verizon before his stroke forced him into early retirement, is among a small contingent of students at the academy with no intentions of going pro. (Nick Stabile, an ebullient 74-year-old known as "Papa Nick," is their de facto leader.) Ironically, with more than 40 years of umpiring experience under his belt, Bush is also among the most polished and most confident students in the class. He wouldn't take a gig in professional baseball even if one was offered to him, though, for fear that "it would do a disservice to the game."

"I don't want to make a mockery of the game I love," Bush said. "I don't want to be out there looking like a fool. When that day comes, I'll take myself off the field. Until such time, let's play some baseball."

Bush also recognizes that his dream of becoming an instructor at the Wendelstedt School will go unfulfilled. But if all he gets out of the program is a bit more know-how and the opportunity to sink his feet into the infield dirt in January, he won't be disappointed.

"I feel calm when I'm on a baseball field," Bush said. "It's hard to explain. A calm comes over me. It's like nothing else is happening."

__________

By the time my final day at school arrived, I figured I had a decent sense of which students would have a chance to umpire in professional baseball. A select few seemed to have it all down pat: the look, the authoritative demeanor, knowledge of the rules, and sound positioning.

My personal evaluations, however, didn't account for their skill at "handling situations," which ultimately means the ability to diffuse the testy encounters with managers, coaches, and players that their calls precipitate. They hadn't yet demoed that part of the job, but even if they had, I'm not confident I could've made a sound determination. Assessing an umpire's ability in this area, after all, is the hardest part of the evaluation process, according to chief classroom instructor Junior Valentine.

"That's something that you have to be placed in the moment to really see how it goes," said Valentine, who umpired in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in 2018. "Because we can simulate situations as much as we want, but until you actually see someone get into it, you can't know for sure."

That ability to take shit without losing it - the ability to endure - is essentially a prerequisite for life as a professional umpire. Lots of people can master the rulebook and, with enough practice, develop sound plate mechanics. But it requires a rare kind of fortitude to stomach the indignities of life in the minor leagues, on and off the field, for the remote possibility of maybe, one day, hitting the big time - where umpires will still take plenty of invective, but from much more famous people and for considerably more money.

That's a fortitude I don't have, but I still wanted a holistic assessment of my performance. One instructor mostly prevaricated, citing the small sample size. (I left too early to get into a live game, which usually happens during the fourth week of the course.)

"I didn't see you get hit by a thrown or batted ball," he said. "So that's a bonus."

Another saw potential, though it was partly based on rumor.

"I heard an instructor say that you were doing a pretty decent job for coming in midway through," said John Libka, who spent the 2018 season bouncing between the Pacific Coast League and the bigs. "Your plate stance is OK; I saw you yesterday, your head height was a little low. But your reaction to plays - the fact that you went to third just right off the bat with a runner on first - was pretty impressive. So I would say if sportswriting doesn't work out, maybe you got a future, I don't know."

I chuckled, thanked him, and turned off my recorder. A couple hours later, I packed my suitcase to catch my flight home, putting my field shoes in last. They were filthy. I had neglected to shine them all week.

No student would've gotten away with that.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.

HEADLINES

- Wild pitches lead Jalisco Charros to 1st Caribbean Series title

- Terrance Gore, speedster who won 3 World Series, dies at 34

- Orioles beat Akin in arbitration, 1st win for teams this year

- McGwire returns to A's as special assistant to player development

- Dodgers cut reliever Banda after 2 World Series titles