Robots are coming for all of our sports - the only question is when

After he slalomed between two defenders and one-timed a bouncing stretch pass to the inside corner of the left post, Peter Stone turned toward a teammate, smiled, and celebrated the dazzling sequence with a shrug.

Stone's showing on an indoor soccer pitch in Sydney, Australia, earlier this summer was dominant by any standard, even though the specifics of the match were unconventional. Outfitted in dress shirts, he and four fellow scientists were coasting past a team of wheeled robots, exploiting holes in their defense with shrewd link-up play and timely saunters down the wing.

Even as he scored four goals in the 4-1 win, Stone - the president of the RoboCup Federation, an international collective of academics that arranges this yearly tussle between man and machine - came away impressed by his opponents' teamwork and smarts. The patterns in which the robots shared possession and moved into open spaces were familiar; they resembled the kinds of decisions that underlie any cohesive lineup's attack.

The robots, standing just waist-high against the humans, managed to make this much clear: They knew what they were doing.

"People are still much better than the robots. We can still pass the ball around them," said Stone, an artificial-intelligence researcher at the University of Texas. "(But) every year, it gets a little bit more difficult. We always joke that we're not sure if it's because we're getting older or the robots are getting better."

RoboCup is a scientific entity. It stages soccer tournaments between teams of robots because its members, first and foremost, want to advance the state of robotics research. However, the goal around which the federation orients its work is rooted in sports. By 2050, the scientists want to build a roster of autonomous humanoids that is capable of competing against the most formidable opponent imaginable: the champion of that year's World Cup.

The 2050 benchmark is an objective, but not a prediction. "We learned long ago in artificial intelligence that if you put a date on a challenge like that, you should do it for a date after you're going to retire, because they're very uncertain," Stone said.

Still, there's no time like the present to wonder when this ambition might be realized - and, once it is, how it will affect each and every one of our games.

In 2019, the makings of a future in which humanoids displace professional athletes and technology renders both coaches and referees obsolete is starting to become discernible. Toyota engineers have developed a stationary basketball robot that sinks set shots with unrivaled accuracy. And not long after he departed Arsenal last year, Arsene Wenger speculated that robots could manage soccer clubs within two decades.

Radar technology is already responsible for calling balls and strikes in the independent Atlantic baseball league, which MLB tapped as its testing ground for a slate of experimental rules. Human umpires still relay the calls to the players and the crowd, but their deference to the automated system means that for the first time, a non-human entity occupies a full-time role in a live sports competition.

"(Players) want to have a consistent strike zone," Atlantic League president Rick White said. "They have consistently in the past said to us, 'Tell us what the strike zone is, enforce the strike zone, but don't change that umpire to umpire, day to day, inning by inning,' and so forth. (The automated system) gives them an answer to that."

Given the novelty of the Atlantic League's trial run, we're a ways off from MLB deciding to computerize its own strike zone. Even further away is the prospect of a robot keeping pace with Kylian Mbappe or outshooting Stephen Curry against the added burden of a defender. Present-day humanoids generally struggle to stand upright, which is why it's far more entertaining for RoboCup to pit wheeled competitors against Stone and his colleagues at the federation's annual gathering.

Those RoboCup competitions, which are broken down into several divisions based on the robots' design, illustrate the core challenge of taking aim at the World Cup champs: Robot athletes must be hardwired to not only think like humans, but to move like them, too.

For now, robots are significantly more intelligent than they are mobile. When Stone's team faced the winners of RoboCup's wheeled "middle size" league, which factors physicality out of the equation, the robots scored their lone goal off a perceptive downfield pass from a defender to a striker.

A second robot goal was nullified, somewhat ironically, when replay overruled a human decision because the ball didn't fully cross the line.

Meanwhile, RoboCup's humanoid event brings to life an old soccer witticism - the one about possession-happy teams preferring to walk the ball into the net. It's the surest way to score in a game where the players, limited in their ability to move freely, lumber down the pitch with a minder in tow, kicking only from a standstill to avoid falling over.

The chasm between the humanoid body and mind helps explain the value that researchers see in RoboCup and other similar projects. If the end goal is scientific progress, then sports - with their quantifiable standards of success - are a useful setting through which to pursue that result, and to test boundaries.

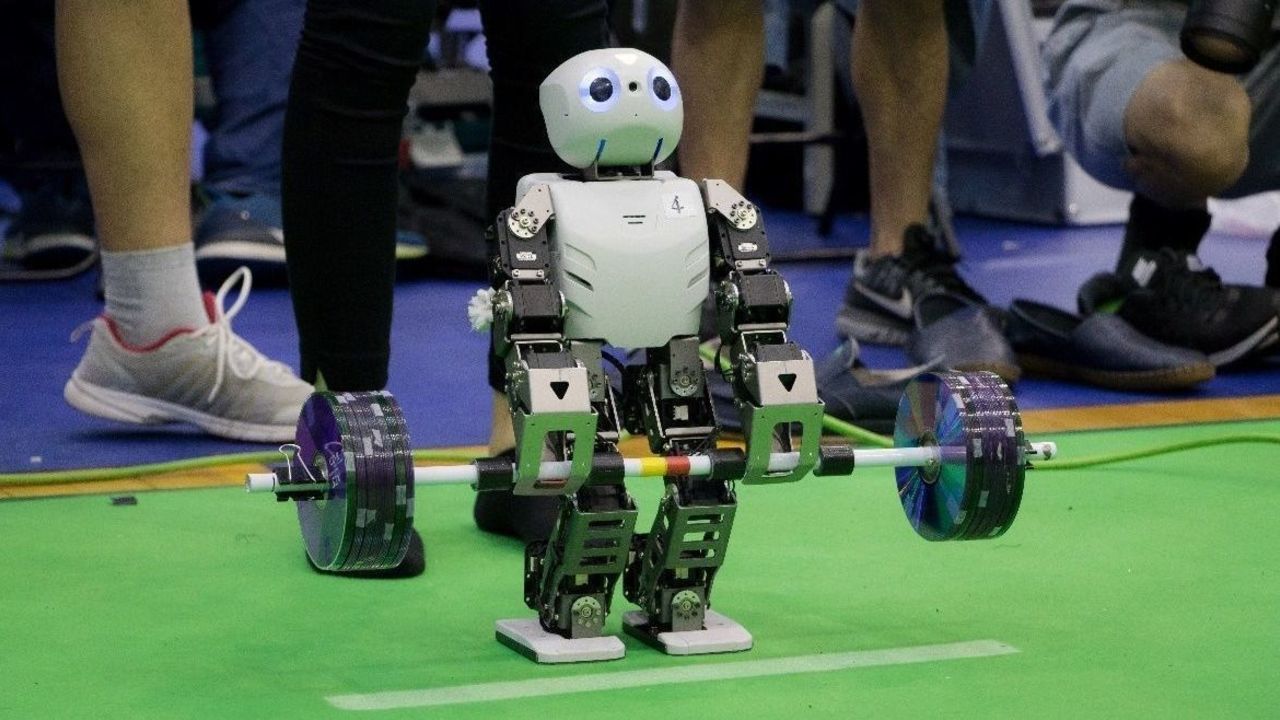

Each year, the Federation of International Robot-Sport Association (FIRA) invites roboticists to enter humanoids they've developed into the HuroCup - the decathlon of the robot world. In the sprint event, participants are made to walk 3 meters forward and then backpedal the same distance. They also weight lift, scale ladders and ropes in a spartan race, and compete in a marathon that spans 421.95 meters, one hundred times smaller than a human course.

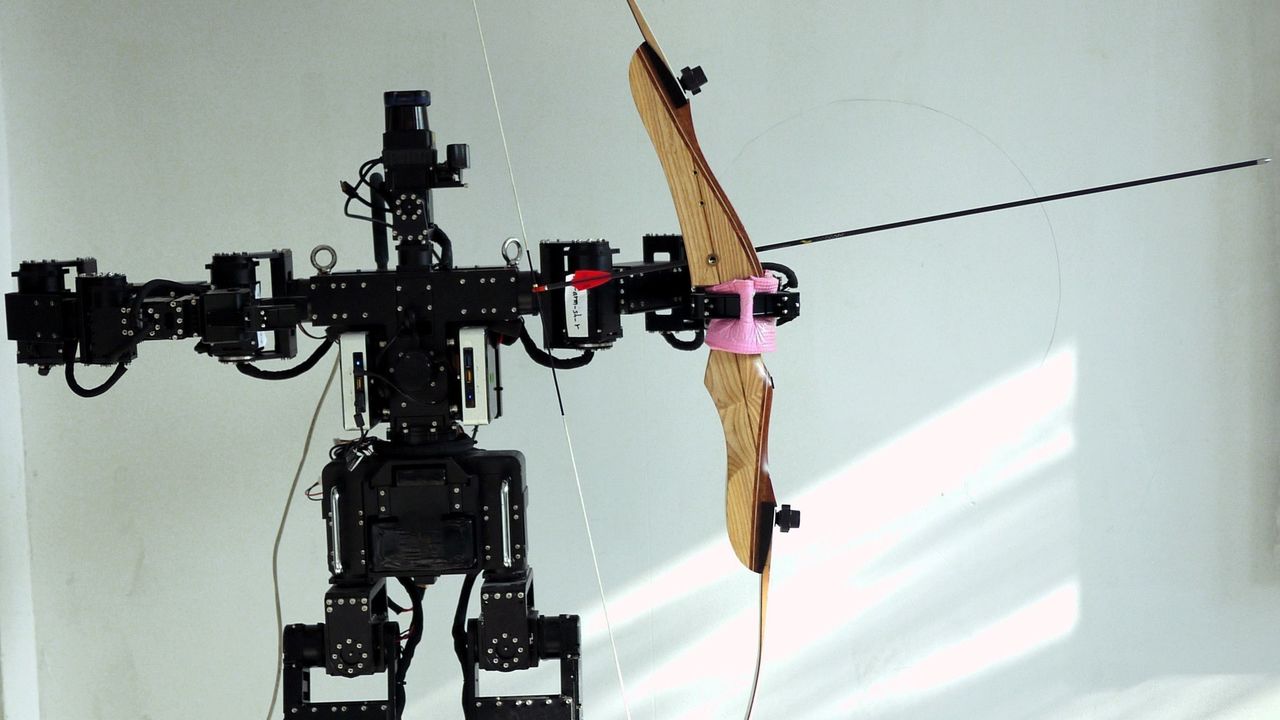

One event in which humanoids could threaten human preeminence rather soon is archery. Jacky Baltes, the president of FIRA and a robotics researcher at National Taiwan Normal University, said that he and several colleagues from around the world are working to enter a robot archer into next year's Taiwanese national competition in hopes that it will later be able to vie for medals at the World University Games, and then at the Olympics.

In contests that require agility and speed, Baltes thinks robots are bound to make exponential strides, similar to other seminal technologies that took time to flourish. He pointed to cellphones, which were once stodgy and heavy but are now small supercomputers. A more extreme example? In 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright kept a plane aloft for 260 meters of flight; by 1947, aviation had progressed to the point where test pilot Chuck Yeager could soar faster than the speed of sound.

We might be 40 years out from a humanoid topping a child in a race of any length, Baltes added, but once the basic framework is in place, it's possible no man-made record will be safe.

"From beating a 5-year-old to beating the world champion is only going to be a relatively short time," Baltes said. "Maybe another five years, maybe another 10 years."

Whenever that time comes, British futurist Ian Pearson figures fans won't take much of an interest in watching those humanoids make precision sports, such as archery and shooting, entirely predictable. "Of course a machine can hit the target," he said.

Pearson applies the same logic to golf. It would be dull, after all, if every round consisted of 18 holes-in-one.

Other sports have greater crossover potential. Robot jockeys could supplant the human element in horse racing, allowing the Triple Crown to be decided solely on the horses' merits. Pearson says he'd be surprised if the next 20 years elapsed without humanoids facing tennis pros in showcase matches. (He noted that this brand of exhibition could be short-lived if the robots reach superhuman physical capacity, enabling them to win all the time.)

As for the people tasked with enforcing the rules? The advent of automated home plate umpires in baseball might be a harbinger of what's to come elsewhere. Pearson has written that robot umps could be practical in tennis, where technology has already replaced humans in calling net cords, and Hawk-Eye is used as a backup resource for line calls. He predicted that drone robots could feasibly take over all officiating duties in soccer by as soon as next year, with humanoid referees to follow around 2030.

If that prognosis seems grim for human officiating, it at least comes equipped with a silver lining: the chance that spectators will revolt at the sight of robots getting every single call correct. "Half of the fun of watching a game is arguing with the referee and calling the guy an idiot," Pearson said.

When the robo-athlete breakthrough arrives, many executives who oversee sports will face a moment of reckoning. How will they act in response?

One option would be to bar robots from our established competitions, which is where Baltes' effort to get a humanoid archer admitted to the Olympics may hit a snag. A spokesperson for World Archery, the sport's governing body, said the federation's rulebook doesn't specify that archers must be human, but does include many prohibitions on the use of electronic equipment.

"I would guess this covers robots," the spokesperson, Chris Wells, wrote in an email.

In the opposite scenario, if marketing potential or the desire to innovate leads sports authorities to welcome robots into the fold, limits on their physical capabilities would have to be enacted to prevent them from making a mockery of the games. Disregard, for a moment, the image of primitive humanoids tottering down a soccer pitch; envision in its place a descendant that's programmed to run with abandon and kick a ball several hundred miles per hour.

"You wouldn't be able to follow the play," Pearson said. "Every shot would be a goal, and it just wouldn't be fun watching it."

About a decade ago, this dilemma led Stone and two fellow roboticists to propose, in a chapter of a book called "Soccer and Philosophy," a set of robot-curtailing rule modifications that would ensure fairness and preserve the essence of the sport, which they described as two teams working to beat each other within the confines of limitations that every player on the field shares.

Their suggested rules stipulate that robot soccer players would need to look like humans, with two arms, two legs, and no more than two forward-facing cameras to serve as their eyes. No robot could be bigger than the biggest human player; none could run faster or kick harder than the upper human limit in each category. Nor could any robo-team's combined size, speed, and kick strength and accuracy exceed the best pro team's total dispersion of those qualities.

"If there comes a time when a team of robots defeats a team of humans under these rules, then no spectator will be able to cry 'foul!'" Stone and his colleagues, Michael Quinlan and Todd Hester, wrote in the chapter.

No spectator, that is, except for those who'd protest the validity of the result on philosophical grounds. When a robot athlete engages in a sport such as soccer, these fans might wonder if they're truly playing the game, or if they're merely mimicking a necessarily human activity.

Stone, Quinlan, and Hester sided with the first response to this question. In their chapter, they argued that if a match in which robots oppose a "serious human team" - be it the World Cup champion or five decently fit scientists - is recognizable as soccer, the robots have sufficiently proven their ability to play.

In 2016, sports philosophers Francisco Javier Lopez Frias and Jose Luis Perez Trivino advocated for a more rigorous standard, opining, in a paper, that participating in a sport is not the same as playing it. In sports, they contend, people - unlike any other being - decide to enter the realm of play to learn something about themselves, such as seeing how close they can get, within natural limits, to attaining physical excellence.

"It's not just about following the rules. It's not about exercising some skills," Lopez Frias said in an interview. "(Playing sports is) about adopting a specific attitude toward the game."

For robots to play sports, Lopez Frias added, more about them would need to be human than simply their outward appearance. If they don't share human vulnerabilities, fans won't be able to relate to them, or admire or care about the wondrousness of any physical feats they conjure.

Future robots may beat us on the scoreboard, or ensure that no pitch off the plate is ever mistaken for a strike again. But under this line of thinking, we'd still be the protagonists of our own games.

"Sport is a human phenomenon," Lopez Frias said. "If you eliminate the human component, then you don't have a sport anymore."

- With a file from Jonah Birenbaum

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.