Why Marvin Miller's long-overdue election completes the Hall of Fame

The Baseball Hall of Fame finally got it right.

Sunday will go down as one of the most important days in the institution's history following the Modern Era Committee's election of Marvin Miller and Ted Simmons. Both men were long overdue for baseball's highest honor, but Miller's inclusion, seven years after his death in 2012, rectified the Hall's most egregious error.

He changed the game

Thought exercise: Construct baseball's Mount Rushmore. The first two names are obvious: Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson. The third name can certainly be debated.

The fourth spot belongs to Miller. You can't tell baseball's story - or the story of major North American professional sports - without him.

When Miller was hired as the Major League Baseball Players Association's first executive director in 1966, owners literally owned the players. The reserve clause - an agreement that bound players to their respective teams forever at a salary of the owner's choosing - was in place, as it had been since the 19th century. The average salary was $19,000 - a pittance, even back then. Baseball's owners, commissioner, and American and National League presidents wielded all the power.

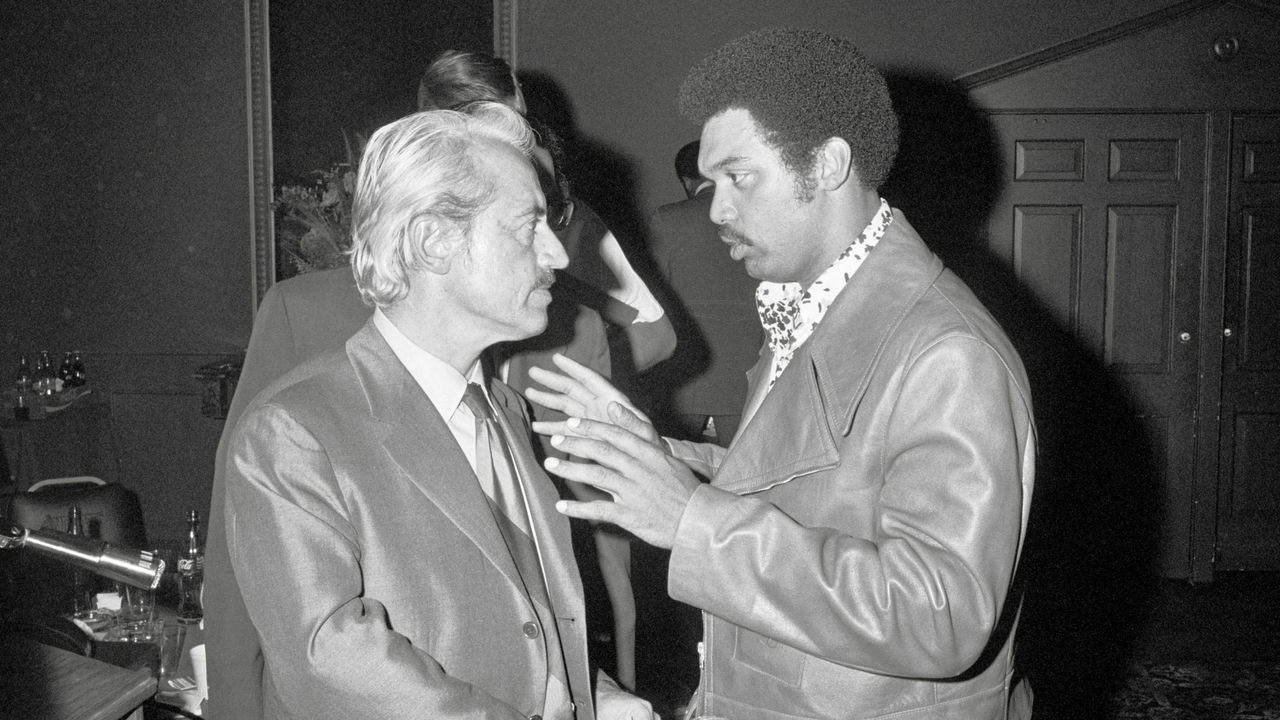

Miller wasn't a baseball man. An economist by trade, he had a labor background and successfully negotiated contracts for the powerful United Steelworkers union. That he had no connection to baseball is likely one of the reasons why he was successful in enacting swift change.

In 1968, Miller won players a minimum salary increase from $6,000 to $10,000 when he negotiated and ratified baseball's first collective bargaining agreement between owners and players. Two years later, a new CBA brought about even more year-over-year increases. By the time he retired in 1982, players earned an average salary of $241,000 and were also set for life with a pension plan that worked. These were stepping stones to future major gains, which would alter the economics of baseball and other professional sports.

But Miller's defining legacy is free agency.

In 1975, he filed a grievance on behalf of Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, who played the entire season without contracts. An arbitrator ruled in Miller's favor, effectively ending the reserve clause and establishing the free-agent market we know today.

Miller's work in baseball changed everything - for sports, labor, and for unionized workers everywhere. Today's multimillionaire athletes, from LeBron James and Mike Trout to that end-of-the-bench fan favorite on a league-minimum deal, all owe Miller a debt of gratitude.

What took so long?

Miller should have been in Cooperstown years ago, and he perceived his snubbing as a hostile, anti-union bias from those on baseball's committees. He wasn't wrong.

That his nemesis Bowie Kuhn - the commissioner who fought to suppress players' rights and keep money in the owners' pockets - and Bud Selig - who presided over the 1994 strike and baseball's steroid era while commissioner, on the heels of his major role in the 1980s collusion scandal while owning the Brewers - got plaques before Miller is inexcusable. That his election didn't come until Miller was seven years dead shows clear cowardice on the Hall's part - everyone knew he would have ripped into baseball's anti-labor establishment if he had taken part in an induction ceremony.

The committees have always stacked the deck against him - executives and owners who took part in the collusion scandal often made up parts of the voting bloc, effectively sealing his fate. Miller was fully aware of why his candidacy couldn't build any momentum, and shortly before his death, he publicly asked to be removed from Hall of Fame consideration following repeated snubs.

In late November, Miller's son, Peter, reiterated the family would likely continue to honor his wishes in the event of his posthumous election. After Sunday's announcement, Peter confirmed relatives won't take part in the July ceremonies.

"As previously mentioned, my father did not wish his name to be placed in nomination for the (Hall)," Peter Miller told journalist Murray Chass on Monday. "And he repeatedly reaffirmed that wish, as well as his desire that I not participate in any HOF activities related to him. So the HOF results this year change nothing. He would, of course, wish the players elected to the Hall all the best for this recognition of their accomplishments.

"I will just add that my father never sought personal fame. And while the case for electing Major League players to the Hall can be based on statistics, the salary numbers that my father is most famous for meant less to him than the simple freedom to choose employers to the extent one's professional ability would allow."

Miller's family should be lauded for standing by his wishes. It sends a powerful message to baseball and the Hall about players' rights at a time when labor relations in the sport are, at best, strained.

But his family's absence won't detract from the magnitude of the moment. Marvin Miller is a Hall of Famer, a distinction he deserves, and his election will hopefully open the door for other labor pioneers like Curt Flood and Scott Boras to join him down the road.

The Eras committees are often criticized, and rightfully so, but on Sunday, the Modern Era voters did what they were supposed to do. They filled a gaping hole in the wall of baseball's national museum and ensured the Hall of Fame will finally be able to tell the true story of the game.

Baseball is better for it.