The life and astounding historical trove of baseball's GOAT statistician

It was winter in California, which meant Bill Weiss, the busiest statistician in baseball, was consumed with piecing together the story of the 1892 San Jose Dukes. Something strange went down on the mound in San Jose that long-lost season, Weiss once told a Sports Illustrated reporter who'd asked him to reflect on his decades of service to the sport. Two pitchers combined to start and complete all but a handful of the Dukes' 170-plus games: George Harper, a righty on the cusp of the majors, and J.D. Lookabaugh, whose yeoman's effort enabled him to hurl more than 800 innings - and whose name, within a couple of seasons, vanished from rosters of the day.

"Probably threw his arm out," Weiss said.

This - the 800 innings; the belated appreciation of Lookabaugh's toil - all took place many years ago, but as vignettes of Weiss' work go, it's evergreen. Weiss was a caretaker of baseball's present and its past, and he was tireless. Across his adulthood he tracked stats for more than a dozen minor leagues. He saved every scrap of information that he unearthed about the game: thousands of books, team batting totals from the 1950 Pacific Coast League season, copies of The Sporting News that dated back to World War I.

His understated explanation for why he bothered digging into Lookabaugh one offseason doubled as a summary of his professional ethos: "I enjoy historical research."

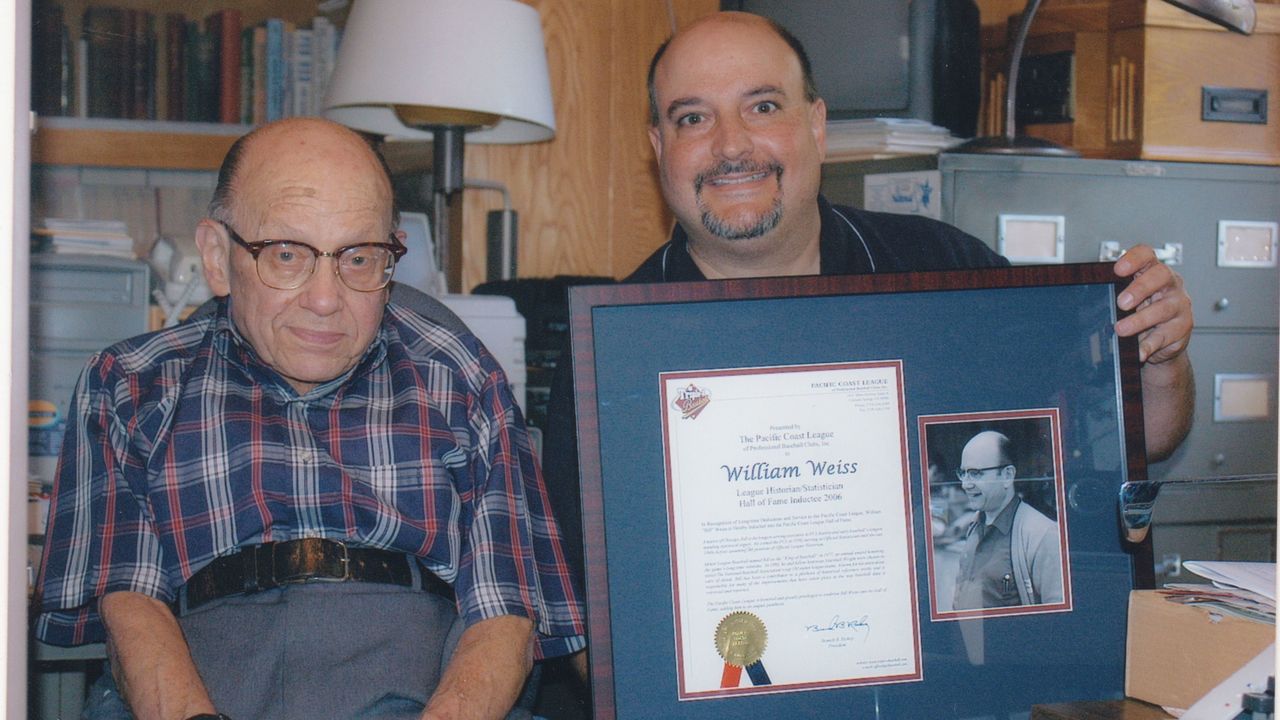

To say the least. Bill Weiss died in 2011, at 86, and his friend Carlos Bauer, a fellow researcher of the minor leagues, remembers him today as the greatest baseball statistician who ever lived. For years, Bauer's been part of a small team of Weiss admirers working to do for him what he did for untold thousands of players from a desk in his bungalow in San Mateo, California. Like Lookabaugh, their contributions to the sport had an endpoint, but a trace of them persists, preserved for the interest of anyone who may ever care enough to know.

When Mark Macrae, the executor of Weiss' estate, organized the contents of his late friend's archive so that it could be transported from San Mateo downstate to San Diego, he filled 650 banana boxes in Weiss' garage. You could commit a lifetime to reading what Weiss compiled in his, Macrae said, and still leave the task halfway incomplete. The saving grace for anyone who'd ever dare to try: with no necessary or obvious entry point, they could start to delve into the material from just about any page.

How about we start with the questionnaires.

For six decades, from 1945 to 2005, Weiss made a habit of mailing biographical surveys to minor-league teams around the U.S., seeking details about most any player who signed a pro contract in that period. The forms asked the players to note their position and home address; their high school and the name of the scout who discovered them; their interests and offseason occupation, if applicable, and assorted memories of their early years in the game.

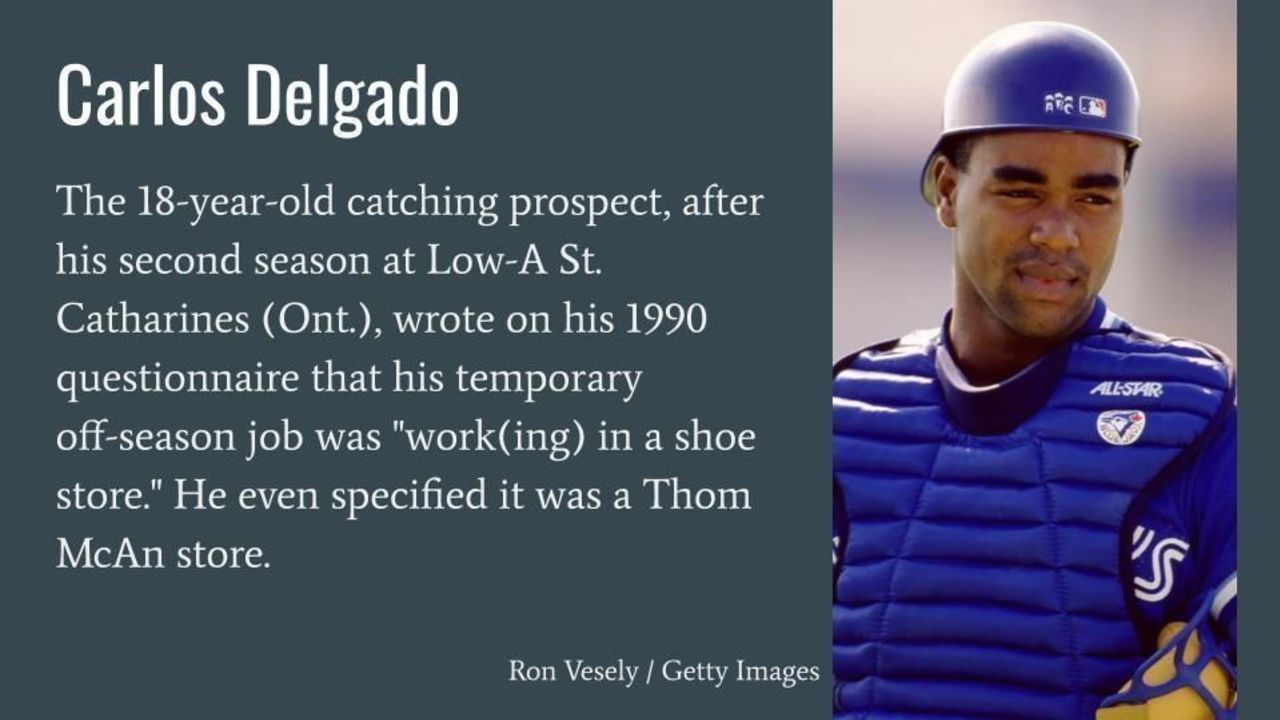

Weiss kept every paper that was returned to him, building a one-of-a-kind collection of personal sketches that as of last year resides in full on Ancestry.com. The questionnaires present firsthand insight into the lives of more than 120,000 young ballplayers, some of whom wrote back to Weiss shortly before they ascended to big-league stardom.

Consider, for example, this sample of current MLB managers, who each answered a Weiss questionnaire at the outset of his playing career:

Writing in 1968, Houston's Dusty Baker recounted his most unusual experience in baseball: briefly delaying a game in Greenwood, South Carolina, because he had to use the restroom.

The Angels' Joe Maddon listed his hobbies in 1975: "Reading, (attempting to) paint, observing people."

Milwaukee manager Craig Counsell's most humorous experience in the game, circa 1992: when the umpire of a summer-league game in Alaska ejected the PA announcer for arguing a call via his microphone.

Yankees manager Aaron Boone's most interesting on-field experience, circa 1994: "Someone lit my shoelaces on fire during a game in college."

Many thousands of Weiss' correspondents were never widely known, though some overlapped with celebrated namesakes. Take Frank Robinson - not the first-ballot Hall of Fame outfielder, but the pitcher who peaked in Triple-A in the years following World War II, and whose 1949 questionnaire hints at his contributions to that cause. This Robinson tossed a no-hitter in Hawaii as a teenager serving in the Marines. In 1945 he helped storm Iwo Jima, the scene of his most interesting experience in the military: getting off the island "under my own power and without injury."

Across the decades, responses betray the earnestness of the writer's youth. In 1953, when Al Kaline was 18, the future "Mr. Tiger" wrote that his ambition in baseball was "to be liked by all the players and fans." In 1966, when Reggie Jackson was 20, the future "Mr. October" revealed his ambition: "To be ½ the ballplayer Willie Mays is." A few years before he was named American League Rookie of the Year, Lou Whitaker blew through the allotted three lines on his 1975 questionnaire to explain that getting to play and love baseball was his greatest thrill.

"Just can't wait until the game start again," Whitaker wrote. "It's just around the corner, few more months."

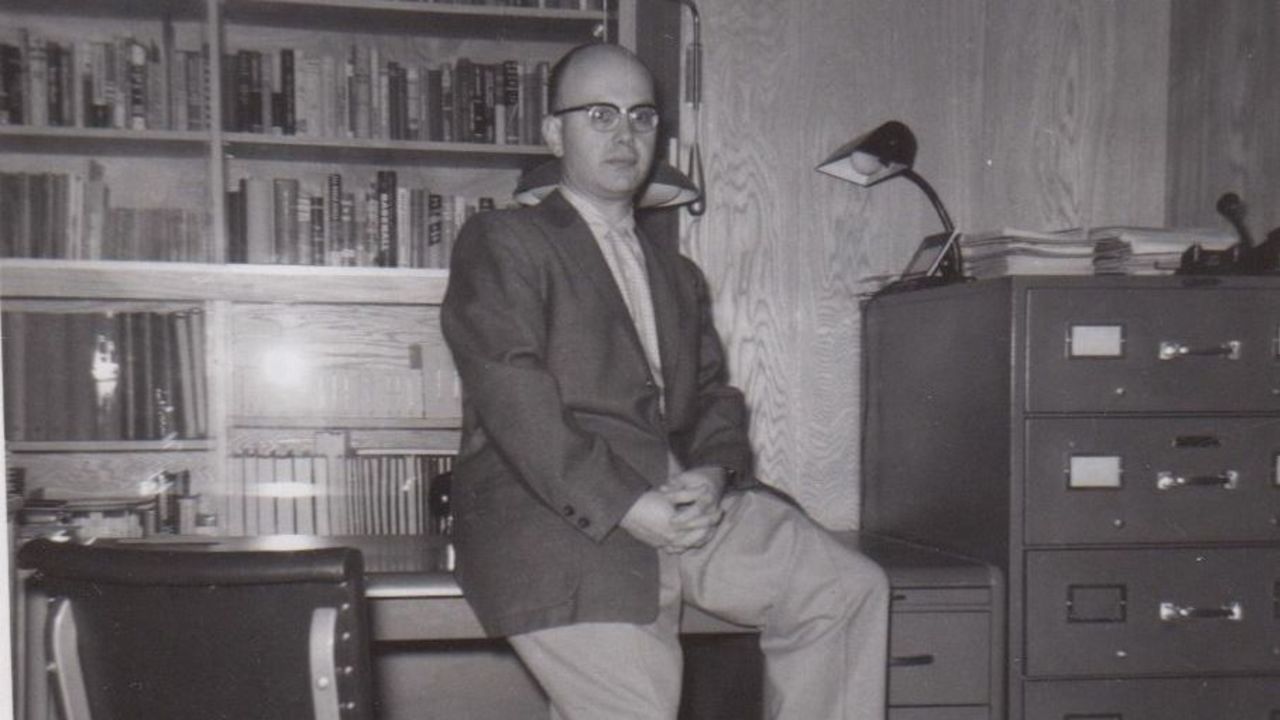

Were Weiss to have filled out a questionnaire of his own, he might have included morsels such as these: He was left-handed. He landed his first jobs in baseball in the summer of 1948, tracking stats for Texas' low-level Longhorn League and managing the box office for a nearby league's Abilene Blue Sox. (He slept on one of two twin beds in the team owner's spare room, as did a succession of players who'd just been acquired.) He moved west to San Mateo in 1950. He kept stats for the Triple-A Pacific Coast League and an abundance of loops that dissolved too soon or that endure today: the Sunset League, the Pioneer League, the Western International League, the California League.

He never had any children. He loved his wife, Faye; black cocker spaniels, of whom they owned several in 56 years of marriage; and baseball, where he found joy in the work.

Weiss was a mainstay at the winter meetings from the 1940s onward. He struck up connections with players, coaches, scouts, and executives; Sports Illustrated's Tom Verducci once wrote in passing in an otherwise unrelated story that Weiss "knew everybody." If a veteran employee of this league or that one retired, his records weren't trashed but shipped to San Mateo, where Weiss built an annex to his home to accommodate the material he couldn't fit in his offices, basement, garage, or enclosed front porch.

"I don't think the man ever threw anything away," said Dick Beverage, a former president of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR).

Weiss was born in 1925 in Chicago, where he first saw the Cubs play at Wrigley Field when he was five, and where he realized in short order that his future in baseball would never be as a player. Indeed, the great irony of Weiss' devotion to his favorite sport was that he didn't get to attend many games. He was drawn from a young age to baseball's recorded history, especially as it pertained to lesser-known minor leaguers, whose stats and backstories were difficult to pin down. When he came to gather stats professionally - and obsessively - he was on call 24/7 from March through October, juggling data from his myriad employers and happily bound to a meticulous routine.

Say a California League game ended close to 10 p.m. in Modesto, 90 minutes away from San Mateo. The scorekeeper would shift his notes onto the official scoresheet and, before the advent of the fax machine, drive the paper to Weiss' home. He'd walk down the long driveway, open a chain-link gate, and circle to the back door. Just inside, Weiss napped on a recliner in his office, cocker spaniel on his lap. The dog would stir, the jingling of its collar waking Weiss, who'd receive the visitor and then step to his desk to type up the numbers.

"The next day, mail comes in," said Macrae, Weiss' longtime friend. "The leagues that were further away, they'd have to mail the stats in. His wife would go down to the post office and she'd pick up anywhere between 30 and 200 pieces of mail, every day. She'd bring them back in and he'd just sit there, type, and analyze."

From the start of his career, Macrae said, Weiss understood the value of the information he stockpiled. Another hallmark of his trove of materials were the sketchbooks, more than 200 in all, that he created in the offseason for minor leagues and MLB organizations. Inside, Weiss included writeups about every prospect in a given system, populated by details he'd gleaned from a range of sources: the player's stats; nuggets from the several dozen local newspapers to which he and Faye subscribed; anecdotes the player had shared in a questionnaire. Before the internet made such content ubiquitous, the books were a go-to resource for teams and insiders across the game.

Weiss abhorred computers, preferring to work on a typewriter. Stats fascinated him partly because they showed how players progressed or faltered, streaked or slumped, day by day and year over year, and his mind was sharp enough to process or recall such numbers on a moment's notice. Tell him a player's at-bat and hit totals and Weiss could determine his batting average without a calculator. Give him the name of someone's grandfather, Macrae said, and he'd know how many games he played for Abilene in 1948.

During the SI interview in which he contemplated his career, Weiss regaled his questioner with a peculiar story about the '48 Longhorn League season. Two games played consecutively that year were monumentally lopsided: the Midland Indians thumped the last-place Del Rio Cowboys 31-0 and then 40-4. In the second game, one poor Del Rio pitcher was left on the mound to go the distance; a mere 29 of the runs he surrendered were earned.

"I didn't see it," Weiss said. "But I've got the scoresheet."

When Weiss died, the first stage of the quest to preserve every such paper in his possession fell to Macrae, a SABR member who met Weiss at a baseball card convention in 1974, when he was 12. Macrae impressed Weiss with his knowledge of players from the early 20th century, prompting the statistician to share his phone number and recommend they keep in touch. Macrae handed Weiss a slip of paper with his name and address.

Their friendship grew over the decades. Weiss made time to chat on the phone in-season during rare breaks. When Macrae was older he'd drive Weiss to baseball dinners around the San Francisco peninsula. As Weiss got older and his mobility became limited, Macrae went to his house weekly to help with bills and to fetch documents for various projects from Weiss' maze of an archive.

"He'd say, 'Go into the back room, take two steps, turn right. Green cabinet. Open the cabinet. Second shelf from the top, center column,'" Macrae said. "And that's how we would find things."

Eventually, it came time for Macrae to organize Weiss' material as best he could, employing his 650 banana boxes in service to the goal of sending the collection to a permanent home. Finding that new guardian took two years. One potential recipient wanted only part of the archive; Weiss had wanted it to remain whole. Plans for another would-be repository - a proposed minor-league museum in North Carolina - fell through for lack of funding.

Instead, a safekeeper surfaced down Interstate 5 in San Diego, whose main public library branch houses an expansive baseball research center. In 2014, the library announced that it had obtained Weiss' trove in partnership with the local SABR chapter. The boxes were driven 500 miles south from San Mateo in four truck trips.

"Long story short," said Tom Larwin, the president of SABR's San Diego Ted Williams chapter, "we got about 16 tons of archival material that moved down from the Bay Area in California - and became my life for a few years."

Larwin is a retired civil engineer who set aside his consulting work when the archive arrived. He and Bauer - the researcher who considers Weiss the GOAT statistician - inventoried the contents of the acquisition over the course of months. They happened across a Navy surplus industrial scanner, on which they began to digitize player and team stat logs, scoresheets from bygone games, and league guides dating to the 1800s. The scope of what Weiss amassed by himself eclipses even Cooperstown, Bauer said: "I don't think they have copies of the official averages of the 1940 KITTY (Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee) League."

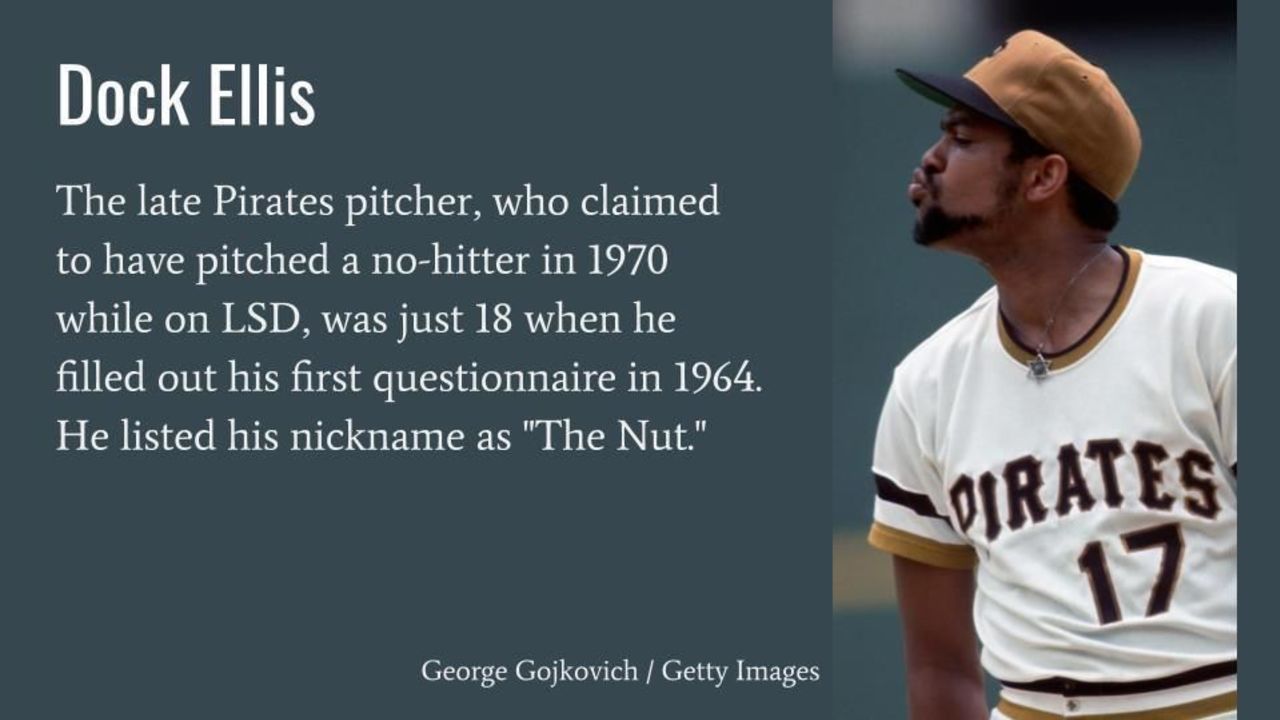

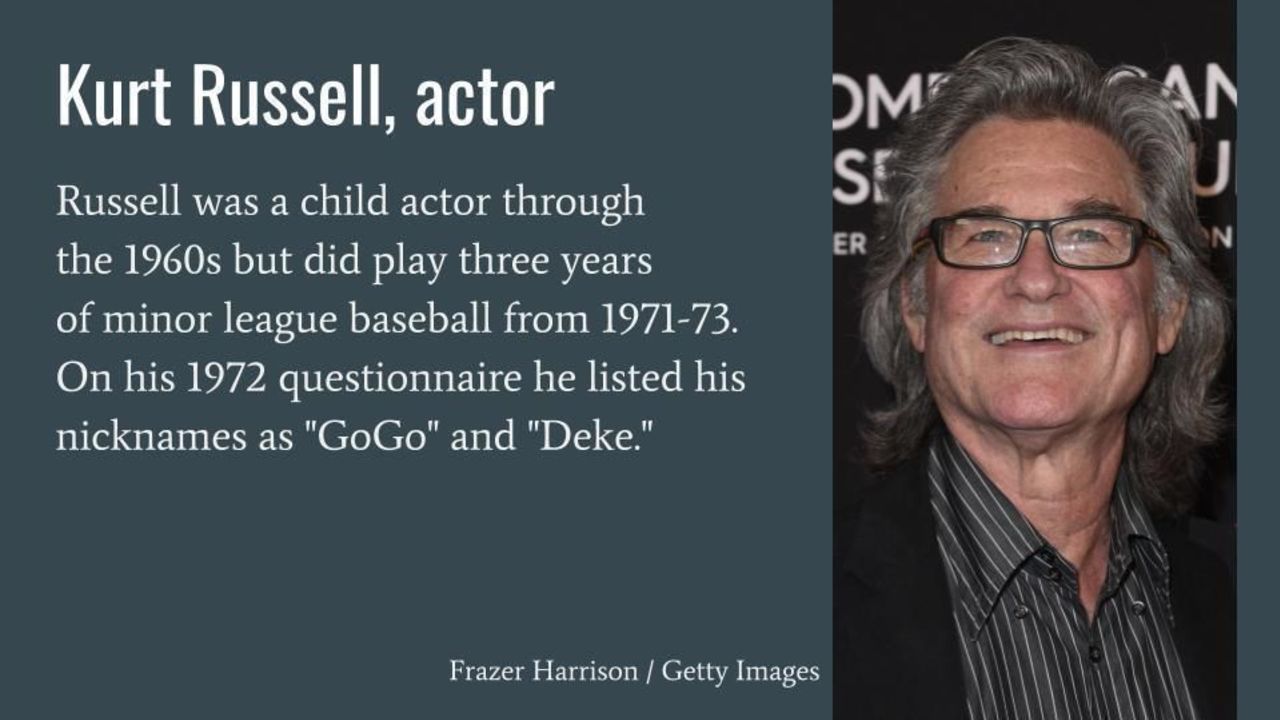

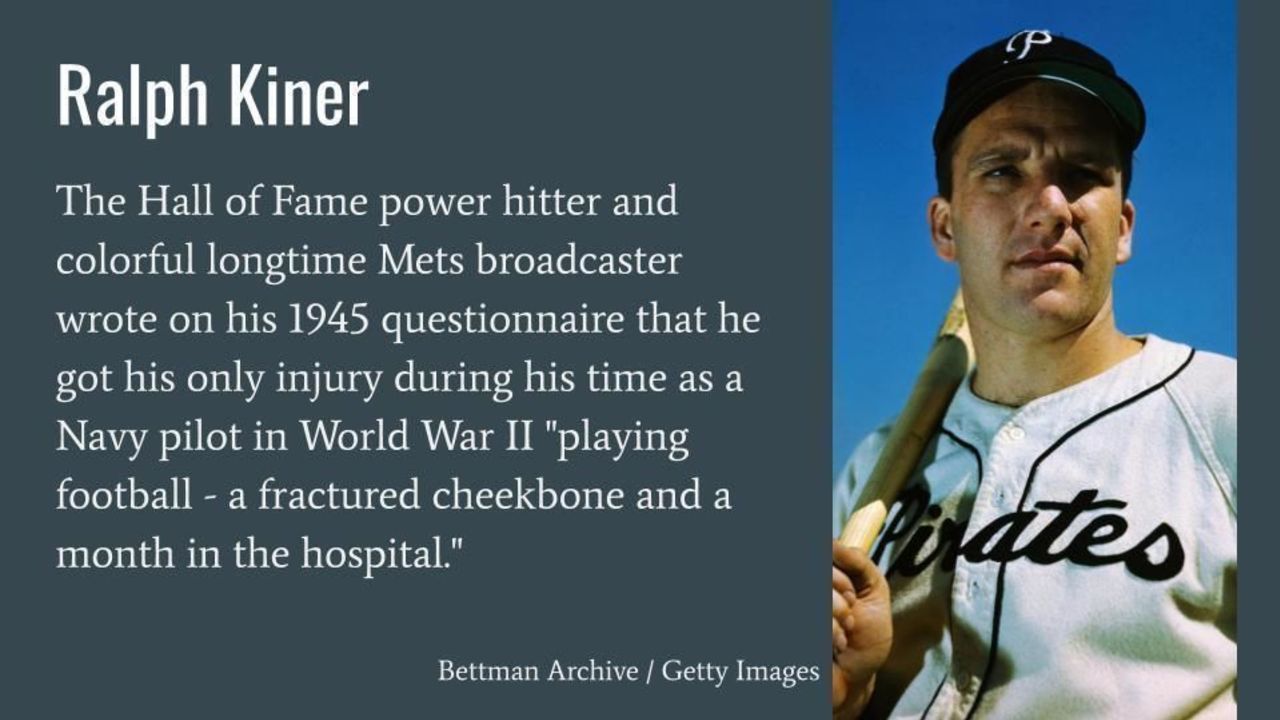

Larwin and Bauer's work remains ongoing, even after they digitized about 20,000 of Weiss' player questionnaires and then outsourced the lion's share of that formidable task to Ancestry. Those images, about 124,000 in all, are now searchable by name on the genealogy company's website. There's Wade Boggs, listing Abner Doubleday as a distant relative (seventh cousin). There's Bob Gibson, recalling a basketball game he played in college against the Harlem Globetrotters. There's Tommy John, hurling 21 strikeouts in a game against inmates at a federal penitentiary. There's John Smoltz, disclosing his adolescent nickname: "Holy."

Larwin and Bauer came to their shared objective - making much more of the archive publicly accessible online - from different positions. Bauer knew Weiss for decades, having met him when Bauer set about producing a Pacific Coast League encyclopedia. Weiss shared what he knew about old players whose stories were elusive; he let Bauer study documents at his home. Bauer came to appreciate Weiss' unique and profound influence on stat-keeping: he cared so much and was painstakingly accurate for so long that he forced other practitioners of the genre to improve.

Larwin, meanwhile, never met Weiss.

"But I feel like I know him very well," Larwin said. "I've read some of his correspondence. I'm touching pieces of paper and pages of books that probably he only touched. I have this connection with him. I can only imagine how baseball consumed his life - to see all these things that he collected."

In his baseball lifetime, this steward of history accrued a few more cherished titles and distinctions. For 25 years starting in 1959, Weiss was president of the Peninsula Winter League, a Bay Area circuit whose alumni include Hall of Famers Joe Morgan and Willie Stargell. He joined SABR in 1971, becoming the nascent organization's 34th member. Minor League Baseball named Weiss its "King of Baseball" for the 1977 season. In 2001, he helped devise for MiLB a ranking of its 100 best teams from the 20th century.

He did it all with Faye by his side. The Weisses took no elaborate offseason vacations; instead they had season tickets to hockey's San Francisco Seals, and unfailingly they stayed busy. Faye handled the daily mail runs; she combed through the sports sections of the newspapers sent their way, seeking miscellany about players that Bill could include in a future sketchbook. Faye was an avid reader, Macrae said; she devoured novels, and read the paper every day until she died in 2018 at 93. Their bungalow was sold that year, he said, and subsequently was torn down.

One day a year or two after Bill died, Macrae headed to the house to inch ever closer to packaging the sum of the man's work. He opened a box of sports-collecting publications from the mid-'70s and found a surprising keepsake, which he pocketed for himself.

Long after he would have memorized the information, Weiss had held onto a reminder of their first meeting: the paper on which a precocious 12-year-old wrote his name and address in 1974.

"There was no reason to save it," Macrae said. "He saved it."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.