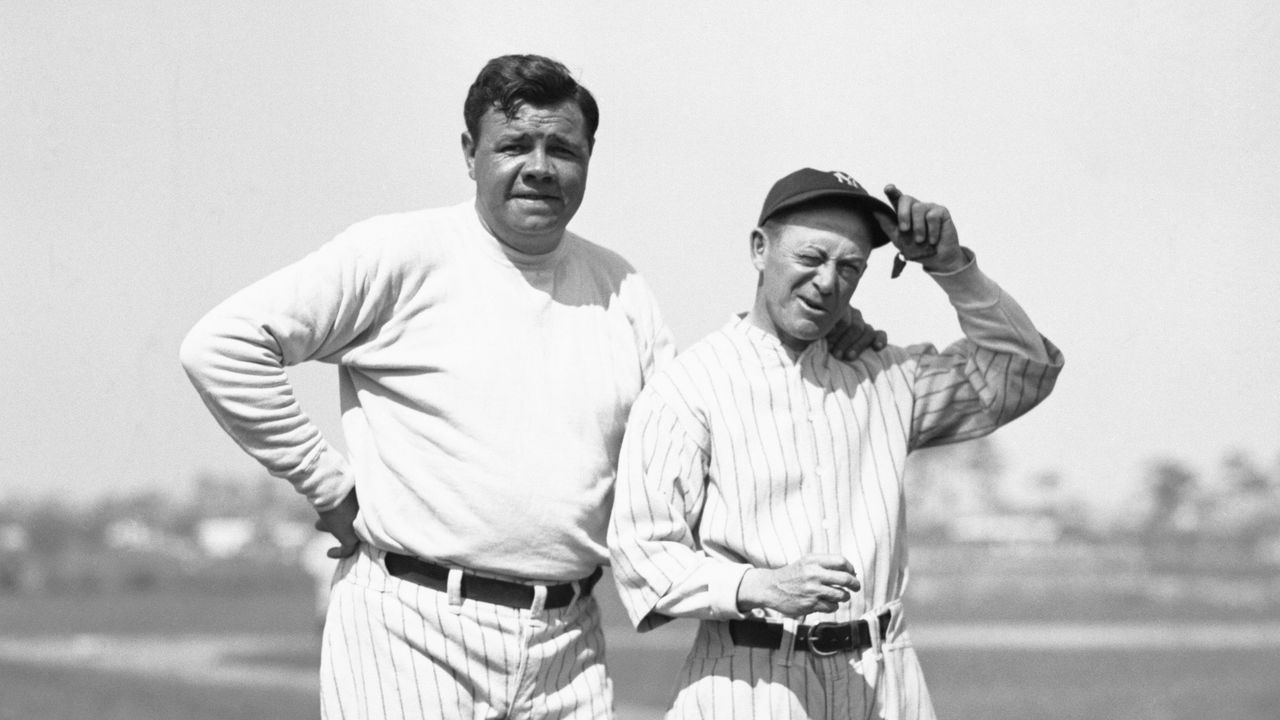

It wasn't just Babe: This forgotten duo made the Yankees unstoppable

Jacob Ruppert never homered for the New York Yankees, but as a baseball owner and brewing mogul, he took mighty swings that were worthy of Babe Ruth. How else to explain the duality of his experiences Jan. 5, 1920? That's when the Supreme Court rejected his legal challenge against the Volstead Act, which forbade the sale of alcohol across America for the next 13 years.

No matter; consolation arrived almost immediately. Jan. 5, 1920 is also the day Ruppert's ballclub acquired Ruth from the Boston Red Sox, paying $100,000 cash to open a championship window that endured for much longer than Prohibition.

Ruppert owned the Yankees from 1915 until his death early in 1939, the span during which the team moved to its namesake digs in the Bronx, shed its reputation as an American League doormat - seriously, the Yankees used to suck - and fielded several of baseball's most memorably dominant lineups. His was the era of Murderers' Row, of 10 pennants and nearly as many World Series titles captured by a franchise that had previously won nothing.

It was also the heyday of Miller Huggins, the team's first great manager and another figure overshadowed in history by the famous paragons of Yankee exceptionalism: Jeter and Rivera, Mantle and DiMaggio, Gehrig and the venerable Bambino. Huggins was the man who convinced Ruppert to pursue Ruth at the end of the sport's dead-ball era, assuring that the Yankees would soon reign dynastically and that Huggins would pale in prominence next to his No. 3 batter.

"It can simplify things: Everything is Babe Ruth," said author Steve Steinberg, whose book "The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees" (out in paperback this month) chronicles Ruppert and Huggins' years in pinstripes.

"These were two guys who worked really quietly in the background," he said.

Steinberg's book, co-authored with fellow historian Lyle Spatz, exists to emphasize that Ruppert and Huggins' contributions to the cause of lording over the AL were, indeed, vital. Even before Ruth's rights were purchased and Lou Gehrig signed, these kindred spirits - two introverted bachelors who trusted each other and shared a singular zeal to win - had started laying the groundwork for the Yankees to become baseball's most frequent champion of the past 100 years.

| Titles | With Ruppert and Huggins | With Ruppert |

|---|---|---|

| AL pennants | 6 (1921 1922 1923 1926 1927 1928) | 4 (1932 1936 1937 1938) |

| World Series | 3 (1923 1927 1928) | 4 (1932 1936 1937 1938) |

Ruppert, a brewer, attained the rank of colonel during his military service in the New York National Guard. He assumed control of the Yankees in 1915 only after he failed to buy the National League's New York Giants, his former favorite team and the Yankees' landlord at the Polo Grounds. Apart from all the winning, Ruppert's crowning achievement as owner was to spearhead the club's move out of Manhattan to an iconic stadium of its own. His management style inspired confidence: Ruppert hired competent people, Huggins and general manager Ed Barrow among them, and empowered them to work their magic without meddling.

Contemporaries of Huggins regarded him as one of the game's sharpest minds. He studied law and captained the baseball team at the University of Cincinnati, where his professor William H. Taft - the future 27th president - recommended that Huggins stick to sports. Weighing in the neighborhood of 120 pounds, Huggins scratched out a path to the big leagues after learning in the minors to bat left-handed, thereby affording himself a closer start to first base when he hit ground balls. As a second baseman with the Reds and Cardinals from 1904-16, he's said to have pulled off the hidden ball trick an NL-record eight times.

Evidently, Huggins was intense. As Steinberg and Spatz recount in their book, New York newspaperman Damon Runyon once joked in print that Huggins had smiled exactly once. Nerves, the authors write, wreaked persistent havoc with his health; illness almost forced him to quit as manager before the 1927 season, when the Yankees legendarily won 110 games. Huggins stuck around despite continual flak from writers who thought him unfriendly, and despite a 1925 incident in which his players' mounting contempt for his authority apparently moved Ruth to dangle him out of a moving train.

Not all of Huggins' interactions with the talent were this fraught, though in 1925 - repudiating the maxim that it's easier to fire a manager than a whole team - he did persuade Ruppert and Barrow to ship out a raft of veteran players who'd crossed him. Shortly before George Halas founded football's Chicago Bears, he played 12 games for the Yankees only to be cut for batting .091; he later wrote that he appreciated Huggins' grace in that tough moment. In the course of winning three World Series together, Huggins also came to earn Ruth's gratitude and respect, the authors write. Gehrig, moreover, considered him a father figure.

"No man ever more thoroughly put to flight his critics and vindicated the confidence his friends had in him," Runyon wrote after Huggins died at 50 in 1929, as cited in Steinberg and Spatz's book. "The results are in the records, and baseball judges its people on records."

One such friend was Ruppert, who recognized and valued Huggins' brilliance - his mastery as a talent evaluator; his ability to manage myriad personalities in a clubhouse - when his detractors didn't. Ruppert came to believe that no other skipper could have lifted the Yankees to equal heights. Huggins won three pennants at the start of the 1920s with stars acquired from elsewhere; he three-peated at the end of the decade with a younger, homegrown roster. A rival AL coach once said that anyone could have won with the '27 Yankees. The greater feat, he added, was Huggins guiding a banged-up and overconfident team to 101 wins and the title in '28.

To state the counterfactual outright: Would the Yankees have thrived to the same degree without Huggins - like if he'd been fired, as some players and press wanted, back in 1920 or 1921? Ironically, Steinberg said, such an outcome might have helped him live longer: The stress he bore daily is what broke him down.

Meeting the question head-on, Steinberg surmised that winning without Huggins would have been difficult even with Ruth and Gehrig around. The manager was small, but he'd have left big shoes to fill.

Absent a critical mass of fans who remember and admire them today, Huggins and Ruppert are, at least, enshrined at Cooperstown and honored in the borough they used to represent. A granite monument to Huggins is positioned past center field at the current Yankee Stadium, next to tributes to Ruth and Gehrig. A Ruppert plaque is there, too, celebrating, in effect, the philosophy that governed how he and his manager operated - and how the franchise has comported itself ever since the dawn of their partnership.

"Second place would never be good," Steinberg said of his subjects. "It's just an edge: They wanted to be the best. They didn't want to settle for anything less than that."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.