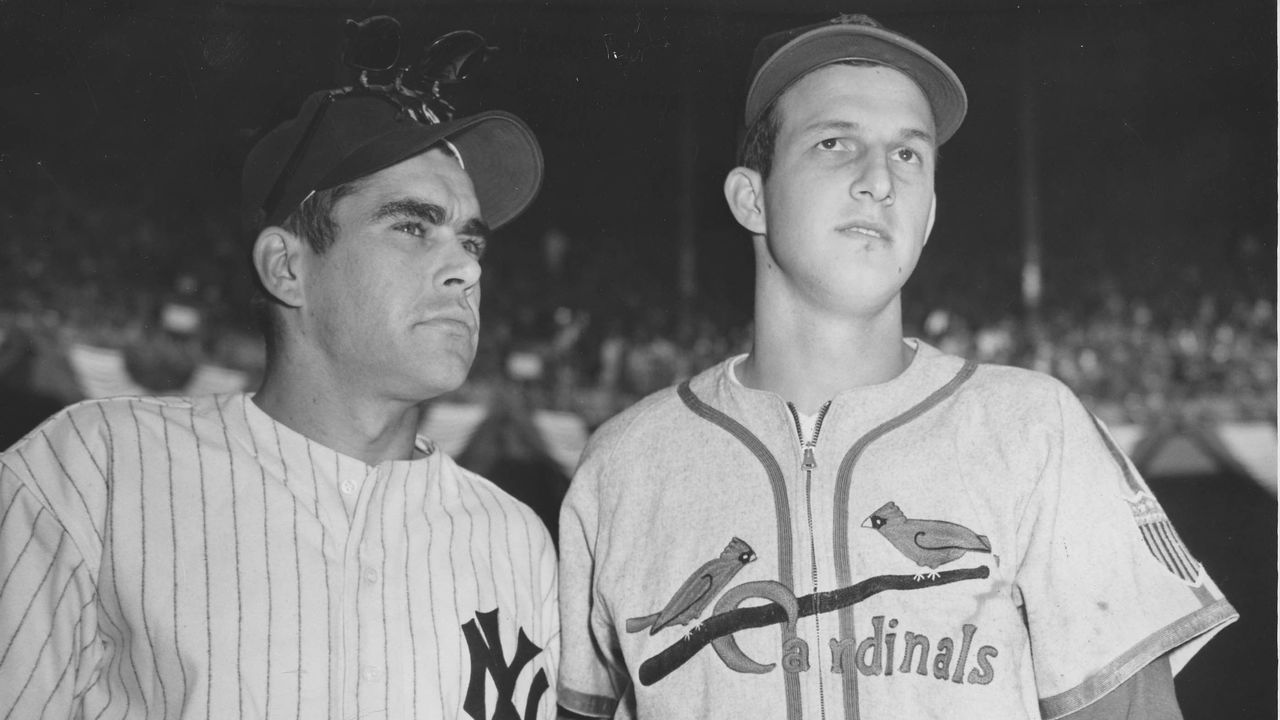

Charlie Keller is the Yankee great history forgot

Hall of Fame debates are a staple of sports arguments - whether a player's amassed the credentials to be honored among the very best in their sport is prime fodder for discussion over a beer. We're spotlighting a collection of players who we believe either deserve the distinction but haven't yet been inducted into their sports' Halls of Fame, or don't quite measure up but had a great impact on their franchise or sport.

Charlie Keller never liked his nickname, a moniker used by fans and writers alike. They called him "King Kong." Rarely did he respond to it.

Still, it fit.

Lauded for his incredible strength, Keller was a legitimate terror to opposing pitchers from the moment he burst onto the scene with the then-indomitable New York Yankees in 1939. He remained one even after a ruptured disc derailed his career in its prime, relegating him to pinch-hitting duties. Were it not for his troublesome back, he likely would've earned a plaque in Cooperstown and a spot in the pantheon of iconic Yankees, residing alongside Ruth and Gehrig and DiMaggio - Keller's longtime teammate - in our collective memory.

Instead, the franchise's best left fielder after the Babe (who split his time at both corner outfield spots) ended up one of the greatest hitters forgotten by history; an unsung hero whose greatness was obscured in real time and whose excellence remains largely overlooked because of the peripheral role he was forced into for so many years.

Let's rectify that.

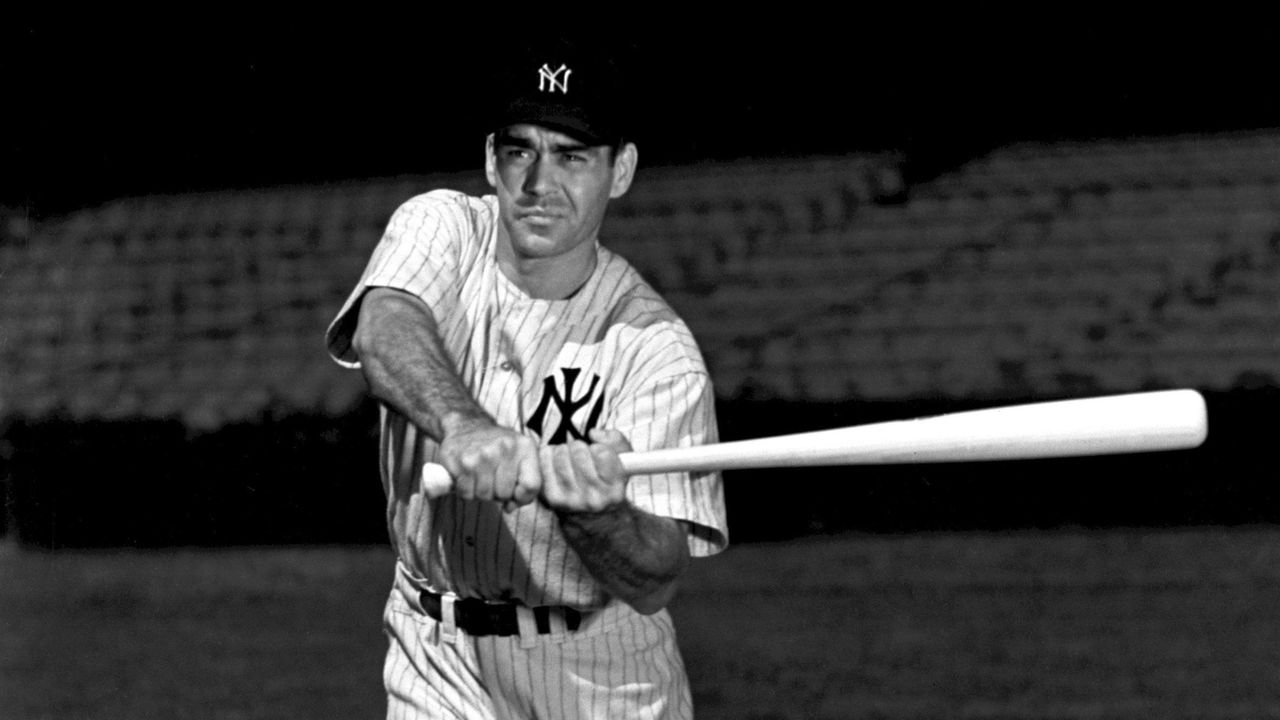

In the summer of 1939, Joe DiMaggio, who had spent the previous three seasons sharing the spotlight in New York with Lou Gehrig, became baseball's preeminent superstar, establishing career bests in both batting average (.381) and OPS (1.119) en route to his first of three American League MVP awards.

Yet it wasn't DiMaggio who shined brightest in the 1939 World Series, which pitted his Yankees - eyeing their fourth consecutive championship - against the Cincinnati Reds. The most impressive player in that 4-0 sweep was Keller, a 22-year-old rookie who went 7-for-16 (.438), clobbering a pair of homers in Game 3, another one in Game 4, and finishing the series with more extra-base hits (five) than the entire Reds roster (four).

His performance came as no great surprise, however, to those who had followed the Yankees all season long. A highly regarded prospect who was named Minor League Player of the Year in 1937 and continued to tear up the International League the following summer, Keller put up a sensational debut season in 1939, hitting .334/.447/.500 over 111 games while accruing 4.9 WAR - more than all but 44 live-ball era rookies - in the shadow of DiMaggio and the Yankees' many other stars, including George Selkirk, Bill Dickey, and Joe Gordon. Keller's monster World Series affirmed that which the rest of baseball had feared: The Yankees had yet another prodigy on their hands.

For the next four seasons, Keller continued to tear up the American League, outhitting (by wRC+) every player in baseball over that span except DiMaggio, Johnny Mize, Stan Musial, and Ted Williams, all of whom were later feted in Cooperstown. In 1940, Keller earned his first of five All-Star nominations, finishing 10th in the majors in WAR (5.6) while managing a .919 OPS and leading the AL in walks (106).

He was even better the following year, setting career highs in WAR (7.3) and home runs (33) and comprising one-third of one of the greatest outfields in baseball history. Keller, an emergent Tommy Henrich, and DiMaggio, who rode a 56-game hitting streak to another MVP award, provided the Yankees with a whopping 22.4 WAR that year. Collectively, they hit .301/.401/.549 and played a large role in snapping New York's one-year World Series drought.

In 1942, for the first time in his young career, Keller outproduced DiMaggio, delivering essentially a carbon copy of his previous season - 7.3 WAR with a .930 OPS - while his more celebrated teammate looked vaguely human, managing what were then career lows in average, homers, and slugging percentage. The next year, in the absence of DiMaggio, who had gone off to serve in World War II along with several other high-profile players, Keller outproduced almost everyone, managing another 7.1 WAR and finishing second in the majors - behind only Musial - in OPS (.922), weighted on-base average (.434), and wRC+ (167).

In total, for the first five seasons of his career, Keller ranked among the game's elite players, producing year-after-year excellence that seemed to put him on the fast track to the Hall of Fame.

wRC+ leaders, 1939-43

| Name | wRC+ | OPS | AVG | ISO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ted Williams | 185 | 1.123 | .356 | .286 |

| Johnny Mize | 168 | .991 | .322 | .261 |

| Joe DiMaggio | 167 | 1.023 | .346 | .257 |

| Charlie Keller | 155 | .942 | .295 | .232 |

| Mel Ott | 154 | .901 | .284 | .205 |

Still, Keller's contributions - and his role within the Yankees dynasty that won three World Series titles in that five-year span - were often obscured by those of his more celebrated teammates. He never placed higher than fifth in AL MVP voting (1941), and he finished 13th in 1943 behind four of his teammates (including the winner, pitcher Spud Chandler).

By all accounts, he was fine with that. Despite his on-field brilliance, Keller - a "real quiet guy," as teammate Phil Rizzuto once put it - eschewed the celebrity that ensnared so many great Yankees before and after him.

"Charlie never liked the attention," Henrich once said. "For that reason, he was never comfortable playing in New York. Oh, he liked playing there, but to him, it was just a job. He was a country boy, and he was happier being back home in Maryland raising his horses."

Keller's resistance to the spotlight perhaps made it easier to forget him once his productivity began to wane, as it did not long after he rejoined the Yankees late in the 1945 campaign, having spent the preceding season and a half serving in the United States Merchant Marine.

Upon returning to the lineup, Keller picked up right where he left off, hitting .301/.412/.577 in 44 games down the stretch for the newly woeful Yankees. Absent DiMaggio, Henrich, and Gordon, they finished well shy of the AL pennant for a second straight year. Keller, then 29, continued to rake the next year for the reconstituted, post-war Yankees, leading the club with 6.6 WAR - edging out DiMaggio again - by virtue of his 30 homers and .938 OPS. But that 1946 campaign proved to be his last as a full-time player.

Roughly six weeks into the 1947 season, Keller began experiencing soreness in his lower back. It didn't relent. Keller's season ended shortly thereafter, with the ailing star making his final appearance as a pinch hitter on June 23. About a month later, a slipped disk was removed from his spine, a procedure that sidelined him through the Yankees' gripping, ultimately victorious seven-game showdown with the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series. It was the beginning of the end for Keller, who largely spent the remainder of his career on the bench, in varying levels of discomfort.

In 1948, Keller appeared in 83 games and started only 60 as the back pain sapped his power; he failed to produce an OPS of at least .900 for the first time, managing a .267/.372/.417 line as a part-time player. He played even more sparingly the following year, logging just 60 games - with the majority of his appearances coming as a pinch hitter. He didn't appear for the Yankees in the World Series, wherein they needed only five games to top the Dodgers again. That winter, the Yankees released Keller.

Keller, however, refused to pack it in. Despite being physically unable to play the outfield, the 33-year-old signed a two-year contract with the Detroit Tigers three weeks after his release to be, in his words, "the highest-paid pinch hitter in the game." And, as it happens, Keller thrived in his extremely limited action. Across 64 plate appearances in 1950, Keller, who started just four times that season, hit .314/.453/.569, providing a valuable bat off the bench for the Tigers. Detroit ultimately finished three games behind the Yankees, the eventual World Series champs.

Keller acquitted himself well in that same role in 1951, posting an .805 OPS in 74 plate appearances in what was functionally his last season. Keller remained unemployed for months after his contract with Detroit expired before re-signing with the Yankees with less than a month to go in the 1952 campaign; he appeared in two games, struck out in his lone at-bat, and was released at season's end, having played his last major-league game at age 35.

More than a half-century since, Keller's memory has faded. His body of work, owing to a steep decline that started early, was too small for him to receive serious consideration for Hall of Fame induction, and time has eroded his primacy to that incredibly prosperous stretch the Yankees enjoyed during his tenure.

But Keller still logged more than 4,500 plate appearances in the big leagues - a sample that ought not to be dismissed outright; it's nearly 1,000 more than Mookie Betts has to date - and put up a better OPS than Frank Robinson, Ken Griffey Jr., and Albert Pujols. He got on base more frequently than Larry Walker, Chipper Jones, and Rickey Henderson. He outslugged the likes of Willie McCovey, Harmon Killebrew, and Gary Sheffield. And after adjusting for league and park effects, he was a more valuable hitter than Edgar Martinez, Miguel Cabrera, and Joey Votto.

If nothing else, that's worth remembering.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.