Bobby Grich is Cooperstown's missing second baseman

Hall of Fame debates are a staple of sports arguments - whether a player's amassed the credentials to be honored among the best in their sport is prime fodder for discussion over a beer. We're spotlighting a collection of players who we believe either deserve the distinction but haven't yet been inducted, or don't quite measure up but had a great impact on their franchise or sport.

Rod Carew, the smooth-swinging second baseman who racked up 3,053 hits with a .328 batting average over his 19-year career, received overwhelming support from the Baseball Writers' Association of America in his first year on the Hall of Fame ballot, garnering 90.5% of the vote to headline the class of 1991.

The following year, a comparably accomplished second baseman appeared on the ballot for the first time. Throughout his career, which spanned from 1970-86, he accrued more WAR than everyone in the game except George Brett, Joe Morgan, and Mike Schmidt - three first-ballot Hall of Famers. And though he wasn't as prolific as Carew in racking up base hits or stolen bases, his power and deftness afield made him, in toto, nearly as valuable.

The voters, however, were unmoved by his body of work. Only 11 members of that year's electorate put a checkmark next to his name. That measly 2.6% of the vote rendered him a one-and-done; players must receive at least 5% to remain on the ballot. Since then, the Hall of Fame's Modern Era committee, one of four auxiliary bodies that effectively exist to give overlooked legends another path to Cooperstown, has failed to even put him on a ballot.

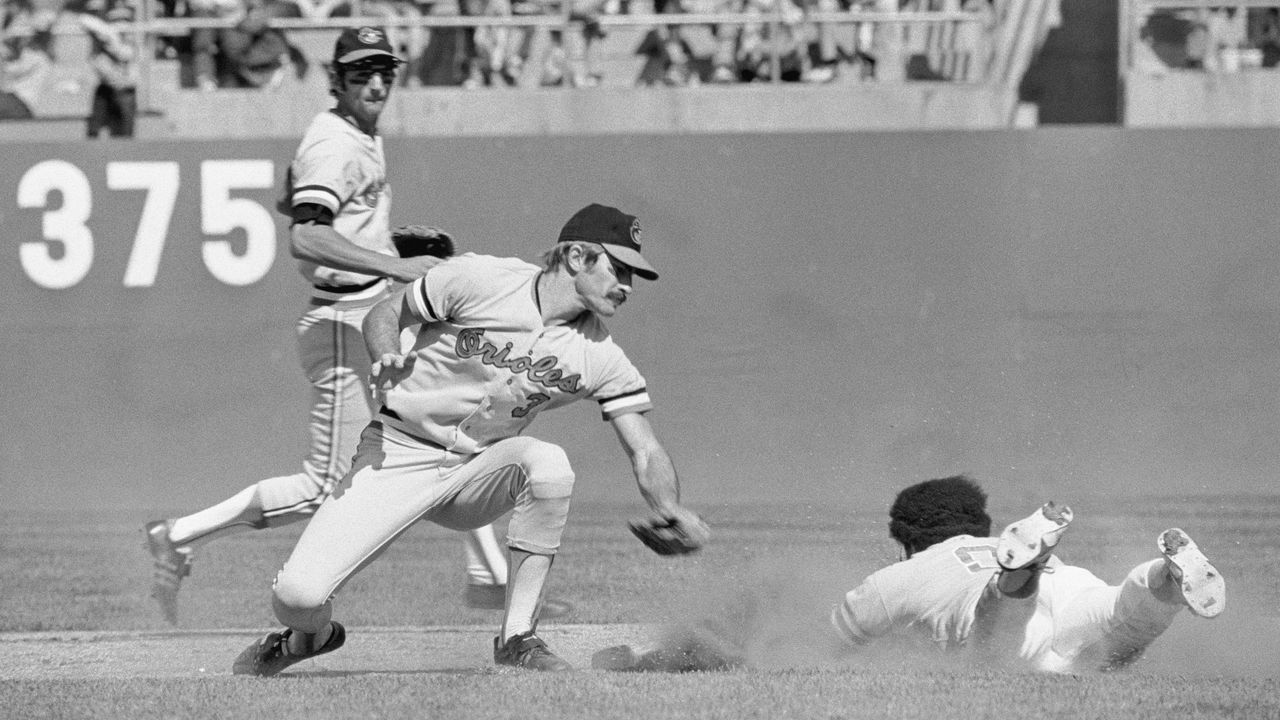

To this day, few omissions are as blatantly outlandish as that of Bobby Grich. The longtime Baltimore Orioles and California Angels star ranks among the greatest second basemen in the history of the game and was unquestionably one of the best players of the early expansion era - even if you've never heard of him.

After hitting .336/.439/.632 in Triple-A in 1971, Grich broke camp with the Orioles for the 1972 season, joining on a full-time basis a juggernaut that had won over 100 games in three straight seasons but was still reeling from its World Series defeat to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The ascendant infielder, then 23, was expected to be a backup, occasionally spelling either second baseman Davey Johnson or shortstop Mark Belanger.

By mid-May, Grich was playing every day. By the All-Star break, he was hitting third in the Orioles' batting order. By summer's end, he had cemented himself as not only the team's best position player but as one of baseball's most promising youngsters, excelling on both sides of the ball. In his first full season, he managed a .773 OPS, good for a 135 wRC+ in an offense-suppressed era, and was the majors' 12th-ranked defender, according to total zone runs. He compiled the second-most WAR (5.4) among both rookies and second baseman, behind Carlton Fisk and Morgan, respectively.

Grich didn't slow down. The Orioles traded Johnson to Atlanta ahead of the 1973 season, so Grich was ensconced at second base after spending considerable time at shortstop the summer prior. He authored arguably the finest campaign of his career, appearing in all 162 games and posting a personal high-water mark of 7.8 WAR thanks to another impressive season at the plate (.760 OPS, 123 wRC+) and an exceptional year in the field (MLB-best 29 total zone runs). For his efforts, Grich won his first of four Gold Gloves, yet he didn't receive a single first-place vote for the American League MVP award, which ultimately went to Oakland's Reggie Jackson (7.1 WAR).

Over the next three seasons, only four players outproduced Grich, who never accrued less than 5.7 WAR, posted a wRC+ below 133, or appeared in fewer than 144 games during that span.

"(He's) as good as any and probably the best ballplayer in the American League," Earl Weaver, the Orioles' indelible manager, told The Sporting News as Grich's free agency loomed following the 1976 season.

Grich's consistency in Baltimore earned him a handsome reward. He landed a five-year deal with the California Angels at an annual base salary of $270,000, though he famously left money on the table to return to his native Southern California. (He and Carew became teammates when the latter joined the Angels two years later, a move that permanently bumped the Panama-born legend to first base.)

But Grich got off to an inauspicious start in California. In the months leading up to his Angels debut, he herniated a disc in his back while trying to carry an air conditioner up a flight of stairs. The injury eventually required surgery, limiting him to 52 games in 1977 and curbing his production through 1978. (It's worth noting that Grich was worth 3.0 WAR in 1978 despite enduring the worst full season of his career offensively.)

In 1979, though, Grich rebounded with aplomb, re-establishing himself as the best player at his position - and one of the best in the game - by unveiling a power stroke he developed by intensifying his offseason weight-lifting regimen. Grich, who had never before eclipsed 19 home runs in a season, clobbered 30 for the Angels that year. He also established what were then career highs in batting average (.294), slugging percentage, (.537), and OPS (.903) to post 5.6 WAR, tops among second basemen. An eighth-place finish in MVP balloting was the closest he came to earning the recognition he deserved.

Two years later, in the strike-shortened 1981 campaign, Grich blew past those marks by hitting .304/.378/.543. He finished tied for the AL lead in homers (22) and sixth in the majors with 5.3 WAR. No other second baseman came close to that latter figure.

Grich earned the last of six career All-Star appearances in 1982, outproducing every second baseman except the indomitable Morgan and emerging star Lou Whitaker. In 1983, Grich was a tougher out than ever before, posting a career-best .414 OBP. That mark would've tied him for second-best in the majors behind only Wade Boggs, but he finished just shy of the qualifying threshold because he missed the final 32 games with an injury.

Even throughout the epilogue of his career, Grich remained a reliable contributor: Despite averaging only 119 games per season from 1984-86, he was baseball's eighth-most valuable second baseman over his final three years in the majors.

Ultimately, Grich's body of work over 17 major-league seasons trumps that of almost every other player who spent the majority of his career at second base. According to FanGraphs, only seven second basemen were more valuable than Grich, who accrued more WAR (69.2) than Cooperstown inductees Craig Biggio, Ryne Sandberg, and Roberto Alomar. Grich also had more WAR than Robinson Cano, a presumptive future Hall of Famer, and Chase Utley, another not-yet-eligible second baseman with a decent shot at induction.

By JAWS score - Jay Jaffe's widely used Hall of Fame evaluation model that averages out a player's lifetime WAR and his WAR during his seven-year peak - Grich ranks seventh among second basemen, ahead of Frankie Frisch, Bobby Doerr, and Nellie Fox, all of whom have plaques. Grich also stroked 224 home runs throughout his career - 13th-most among second basemen - despite playing in an era when homers weren't nearly as prevalent as they are today. His 129 wRC+ ranks seventh-best at his position among those with at least 5,000 plate appearances, and the six players ahead of him on that list have all been granted baseball immortality at Cooperstown.

So why didn't he get in? Well, for one, Grich reached none of the milestones and hit none of the hallowed benchmarks that voters historically fetishize. He didn't reach 3,000 hits, as Biggio and Carew did. In fact, Grich didn't even get to 2,000 hits, finishing his career with 1,833. He didn't hit .300, as Charlie Gehringer and Alomar did, finishing his career with a comparatively unimpressive .266 mark. He didn't drive in 1,000 runs, as Sandberg did, or steal 400 bases, as Frisch did.

Unfortunately for Grich, voters in 1991 generally weren't sophisticated enough to see past those ostensible demerits and evaluate him appropriately. Sabermetrics hadn't yet penetrated the mainstream. "Moneyball" was 12 years from publication. And the areas in which Grich excelled - getting on base and playing defense - remained chronically undervalued.

Nearly three decades later, however, we know better. Our collective understanding of value is exponentially greater, as is our ability to measure and articulate that value. Through the clarity of a modern lens, it is easy to see that Bobby Grich is unequivocally one of the best to ever play his position, and his absence from the Hall of Fame is indefensible.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.