Dick Allen, the oft-maligned superstar, played angry - understandably

This story ran in June as a part of our Hall Pass series on players who we believed deserved hall of fame distinction in their sport but hadn't yet been recognized. Phillies great Dick Allen died Monday at the age of 78.

Warning: Story contains coarse language

"(Dick) Allen never did anything to help his teams win," Bill James, the baseball historian and father of sabermetrics, wrote in his 1994 book, "The Politics of Glory." "And in fact spent his entire career doing everything he possibly could to keep his teams from winning."

No quote more aptly sums up the injustice that has forever shrouded Dick Allen, the polarizing phenom who was one of the best hitters of his era. He was a prodigious slugger who spent a decade out-mashing his most celebrated contemporaries, including Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Roberto Clemente. However, Allen doesn't occupy a privileged spot in our collective memory, nor does he have a plaque at Cooperstown despite a compelling resume highlighted by seven All-Star nominations, an American League MVP award, and a higher JAWS score than Hank Greenberg, Harmon Killebrew, and Orlando Cepeda - three venerated Hall of Famers who, like Allen, did little on defense to bolster their cases.

Instead, as James' take lays bare, Allen endures in the minds of many as a cancer, a surly, militant malcontent who sparked controversy wherever he went throughout his 15-year career. And that's if he's remembered at all. Rarely does Allen name's surface in discussions of the greatest players of the nascent expansion era, even though he raked his way to more WAR from 1964 through 1975 than every position player except Aaron, Carl Yastrzemski, and Ron Santo.

To be sure, Allen was angry for much of his career. He admitted as much in his 1989 memoir. As a Black man dogged by virulent racism from his first day as a professional until his last, Allen had ample reason to be angry, and while fair-minded people can disagree on whether or not he belongs in the Hall of Fame, it can't be denied that Allen's brilliance remains both shamefully overlooked and too greatly clouded by his unflattering (and, according to many, undeserved) reputation as an unmanageable outlaw. His reputation was largely forged via racism and perpetuated today by those unwilling to properly account for the sociohistorical context of the time in which he played.

Let's rectify that.

In 1963, six years after the governor of Arkansas called in the National Guard to forcibly prevent integration at a capital city high school, the Philadelphia Phillies dispatched Allen to their Triple-A affiliate in Little Rock, citing a need for more minor-league seasoning even though the ascendant 21-year-old had scorched Eastern League pitching the season prior and led the big-league club in homers that spring. Never before had the state seen a professional ballplayer who was Black. Yet, the Phillies neglected to brace Allen for the tremendous hostility he would receive and offered him no support throughout a horrific summer in which white fans brought placards to the season opener reading, "Don’t Negro-ize Baseball," and others using the N-word. They routinely shouted racial epithets at Allen during games, and he quickly grew bitter.

"Maybe if the Phillies had called me in, man to man, like the Dodgers had done with Jackie Robinson and said, 'Dick, this is what we have in mind. It's going to be very difficult but we're with you,' - at least I would have been prepared," Allen explained in William C. Kashatus' "September Swoon." "I'm not saying I would have liked it. But I would have known what to expect. Instead, I was on my own."

Allen raked nonetheless, hitting .289/.341/.550 in 145 games with Arkansas while leading the International League in home runs (33), triples (12), and runs batted in (97). By the time he was summoned to Philadelphia that September for his first cup of coffee, Allen had soured toward the organization. The groundwork had been laid for an untrusting, tempestuous relationship.

In the spring of 1964, the Phillies - the last National League club to integrate seven years earlier - began to undermine their budding star, inexplicably referring to him as "Richie" despite Allen's protestations. The press corps followed suit.

"To be truthful with you, I'd like to be called Dick," Allen said, per Rich D'Ambrosio's "The Year of Blue Slow." "I don’t know how the Richie started. My name is Richard and they called me Dick in the minor leagues.

"It makes me sound like I'm 10 years old. I'm 22 … Anyone who knows me well calls me Dick. I don't know why as soon as I put on a uniform it’s Richie."

His frustration notwithstanding, Allen soon emerged as the club's best hitter and one of baseball's most electric youngsters. He hit .318/.382/.557 over 162 games while finishing third in the majors with a whopping 8.2 WAR. He handily won the National League Rookie of the Year award, finishing with all but two first-place votes.

Yet, fans in Philadelphia were reluctant to embrace the young phenom, pelting Allen with boos for his shoddy defense at third base. He led the majors with 41 errors as he tried to acclimate to a new position; fans placed undue blame on him for the club's stunning collapse down the stretch, the "Phold of '64," wherein the Phillies lost 10 of their final 12 games to squander what would've been their first pennant since 1950.

The racial tension that gripped the city that summer, culminating with three days of riots in late August, no doubt factored heavily into fans' treatment of Allen, as well as the press corps' framing of his role within the collapse.

If there existed any chance of salvaging the relationship between Allen and the fans, it was gone by the following summer, when a fight with teammate Frank Thomas, who made a racist remark during batting practice one day, unjustly rendered Allen a villain in Philadelphia. Allen, irked by Thomas' comment, confronted the 36-year-old former All-Star. Words were exchanged. Fisticuffs ensued. Thomas grabbed a bat and hit Allen on the shoulder. Eventually, the two were separated by teammates.

Thomas, a veteran in rapid decline, was released following that night's game. Allen, who was banned by the Phillies from talking to the press about the incident, was ultimately blamed for the fight and Thomas' release, cementing his reputation as a cancer. He hit .302/.375/.494 that summer, finishing eighth in the majors in WAR (6.3) while earning his first All-Star nod and receiving down-ballot NL MVP votes.

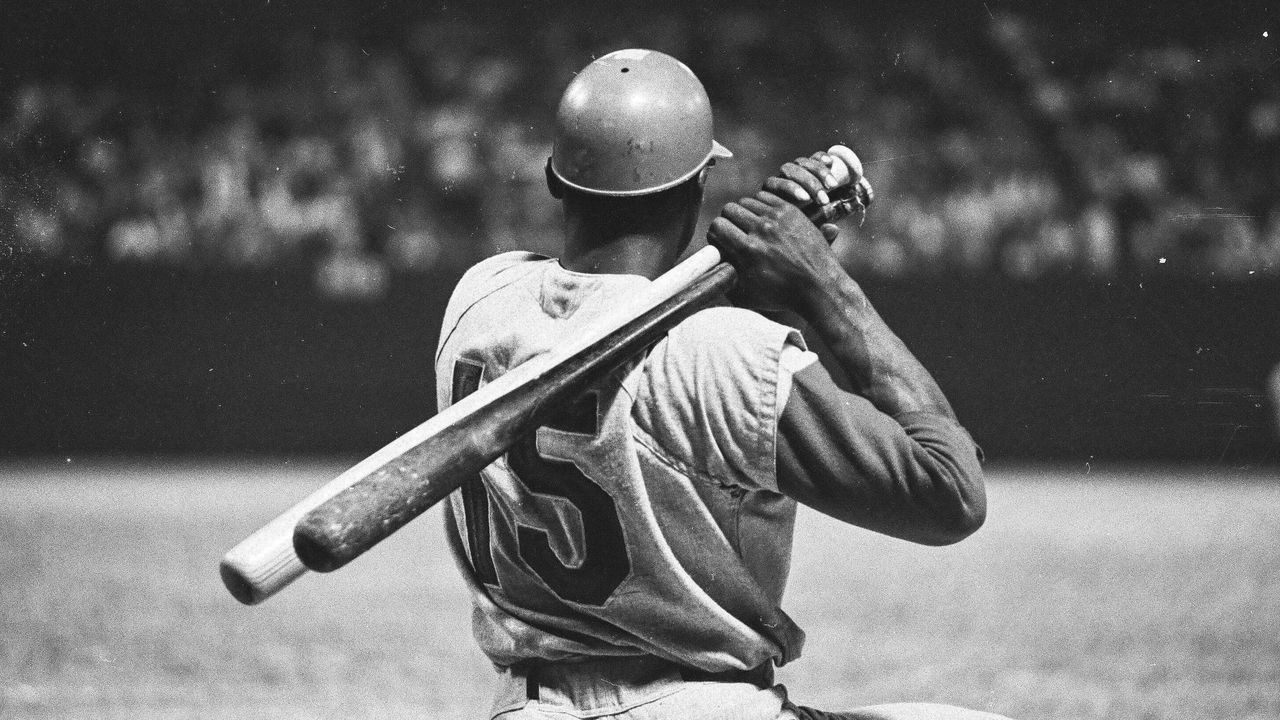

And so it went. Allen kept hitting. The fans kept showering him with hostility. Controversy, for one reason or another, persisted. In 1966, Allen managed career bests in homers (40) and OPS (1.027) as the Phillies stumbled to a fourth-place finish in the NL. That summer, he also started wearing a batting helmet to protect himself from the projectiles being hurled at him by his own fans. (Bob Uecker dubbed it a crash helmet, gifting Allen his nickname, "Crash.")

In 1967, Allen was once again one of the game's top players and led the NL in OPS (.970) for a second straight year. But his season was marred by two incidents. First, Allen, who started drinking heavily early in his major-league career, showed up to a July game late and disheveled. It fueled fans' contempt for him, and he shortly thereafter expressed his desire for a trade.

"I'd like to get out of Philadelphia," he told the Delaware County Daily Times. "I don’t care for the people or their attitude, although they don’t bother me or my play. But maybe the Phillies can get a couple of broken bats and shower shoes for me."

A trade never materialized, and with about a month to go in the season, Allen suffered a freak injury while working on his car one night, tearing two tendons and severing a nerve in his hand when it slipped and went through a headlight. After a lengthy operation, Allen was given only a 50-50 chance of playing again.

He returned in time for the 1968 campaign, much to the doctors' surprise, but from that point onward, after years of largely undeserved scorn and in the wake of a harrowing injury, he was increasingly inclined to lean into the renegade persona that had been authored for him. He would regularly show up late to the ballpark and was often fined.

Still, he kept hitting. In 1968, the so-called "Year of the Pitcher," Allen was one of only seven hitters to reach the 30-homer plateau and finished sixth in the majors in OPS (.872). The following year, Allen delivered another stellar offensive performance, managing a .949 OPS with 32 homers, but not before his relationship with the Phillies became irretrievably broken.

After being suspended for lateness in June - a suspension he learned about over the radio while on his way to the ballpark - Allen went into exile, staying away from the club for nearly a month while being fined $1,000 per day. Upon his return, a disillusioned Allen started signaling his frustration with his club's still-hostile fans by writing words in the dirt while manning first base, scribbling out "BOO" and "OCT 2" - the date of the Phillies' last game of the year. At season's end, the Phillies traded Allen to the St. Louis Cardinals, much to his delight.

"I'll play first, third, left. I'll play anywhere - except Philadelphia," Allen famously said.

So began the second act of Allen's turbulent life in baseball, a nomadic stretch wherein he played for five teams (including, inexplicably, the Phillies again) over a seven-year stretch. But he hit everywhere he went and wasn't subjected to the major controversies that marred his first stint in Philadelphia.

In 1970, his lone season with the Cardinals, Allen earned his first All-Star appearance in three years, hitting .279/.377/.560 while slugging 34 homers in a campaign shortened to 122 games due to a late-season torn hamstring. Shipped to Los Angeles at season's end, Allen turned in another brilliant season in 1971, accruing 5.2 WAR while appearing in 155 games for the Dodgers, his most since his sophomore season.

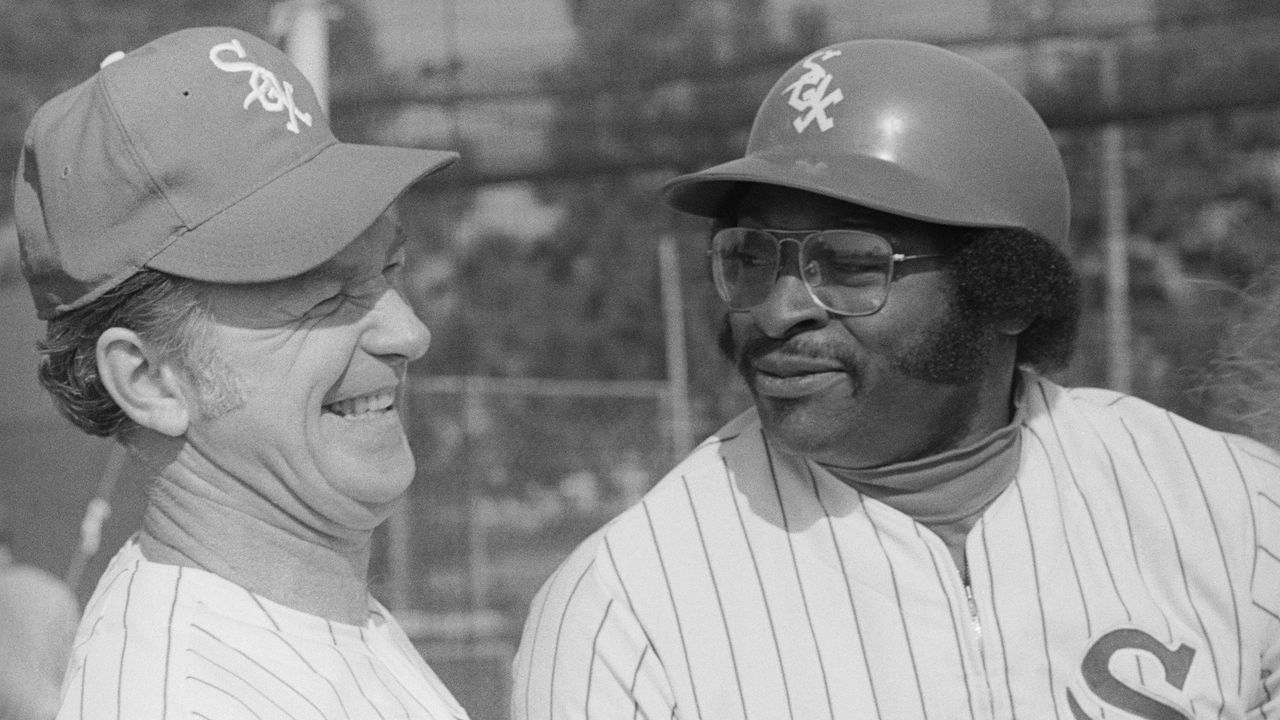

Another trade - his third in as many years - followed that winter. It was so wearying that Allen considered retirement, but a conversation with his mother convinced him to report to the Chicago White Sox in 1972. The best season of his career followed. Allen, who turned 30 shortly before Opening Day, led his league in on-base percentage (.420), slugging percentage (.603), home runs (37), RBI (113), walks (99), and WAR (8.0) en route to the AL MVP award. That winter, he signed a three-year deal worth an estimated $700,000 to stay in Chicago, where, incidentally, the media didn't insist on calling him by a name he disliked.

After two more excellent yet injury-shortened seasons with the White Sox, Allen, at 32, told his teammates he intended to retire. Instead, he ended up playing another three seasons. The Atlanta Braves acquired his rights from the White Sox for the 1975 campaign, but Allen refused to report. Instead, the Braves sent him to the Phillies.

Naturally, the reunion had some hiccups, but he was received warmly by the fans upon his return and helped the Phillies snap a 26-year playoff drought in 1976. Allen played only one more year in the majors after that, stumbling through 54 games with the Oakland Athletics in 1977 before ending his season - and his career - in June.

Over his 15 seasons in the majors, Allen slugged 351 home runs and slashed .292/.378/.534, putting up an OPS (.912) that was, on average, 51 percentage points better than league average. In fact, after adjusting for league and park effects, only a dozen hitters in the live-ball era have been more dangerous than Allen, and all of them are in the Hall of Fame save for Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, and Mike Trout, who's not yet eligible. Allen, as one of the greatest hitters who ever lived, deserves to be there, too, even though he didn't enjoy the longevity those others did.

More so, Allen deserves to be remembered not as some combustible liability who spread discord wherever he went, as James posits, but rather as a victim of circumstance who was treated with near-constant disrespect and still managed to thrive.

He was disruptive at times. He was difficult at times. He played angry, always.

But can you blame him?

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.