Southwestern Ontario is the cradle of baseball in North America

Everything that's special about baseball - the huge hits, the lore, the serenity of watching a game on a cloudless summer evening - coalesced this August at the oldest ballpark in the world.

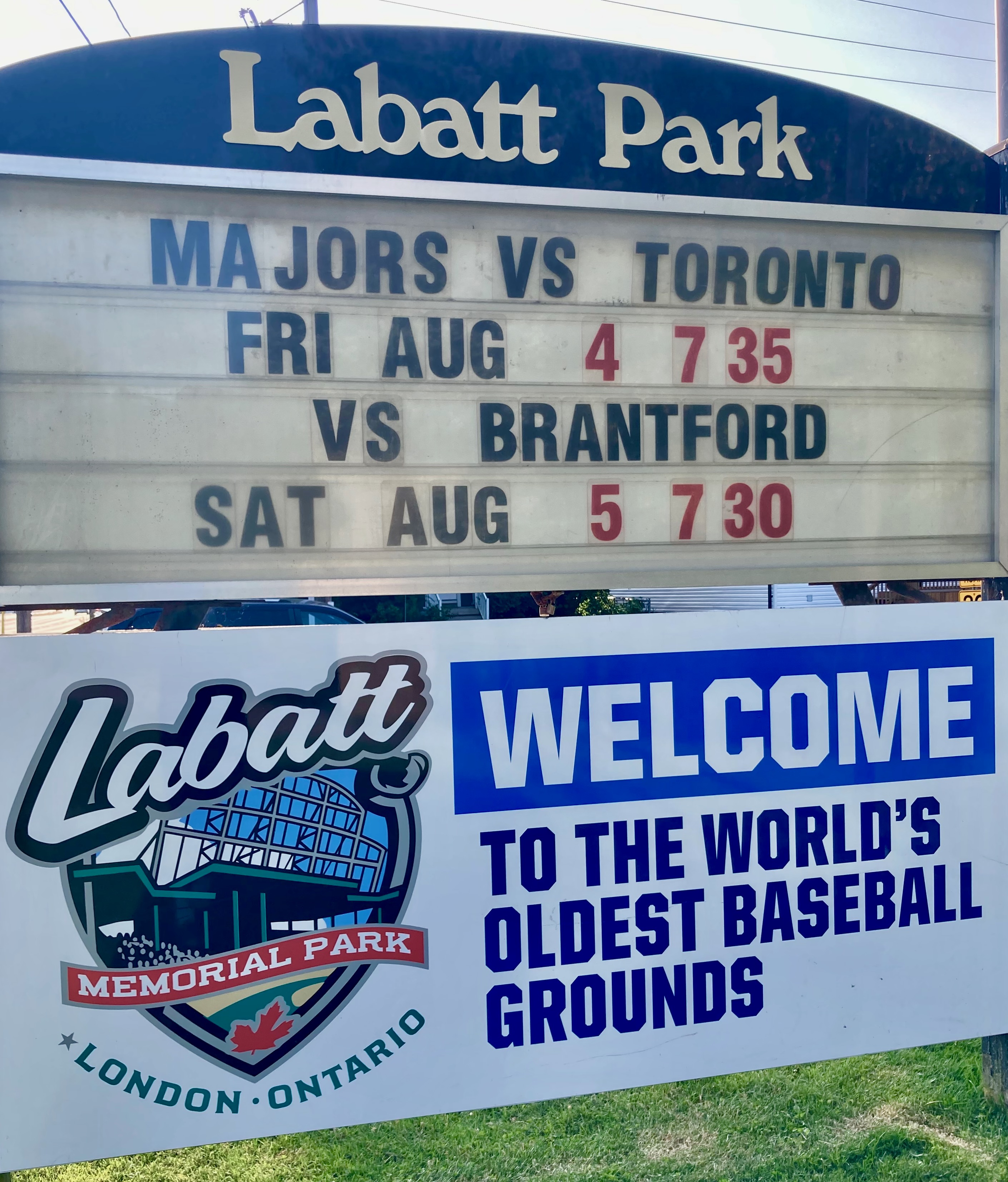

Labatt Memorial Park in London, Ontario, is the 146-year-old home of the London Majors, the reigning champions of the amateur Intercounty Baseball League. Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, and Satchel Paige competed on the diamond in the distant past. Cy Young pitchers have toed the rubber for the Majors. A World Series winner retired from the bigs, moonlighted as an IBL superstar, and eventually began to coach London's recent opponent.

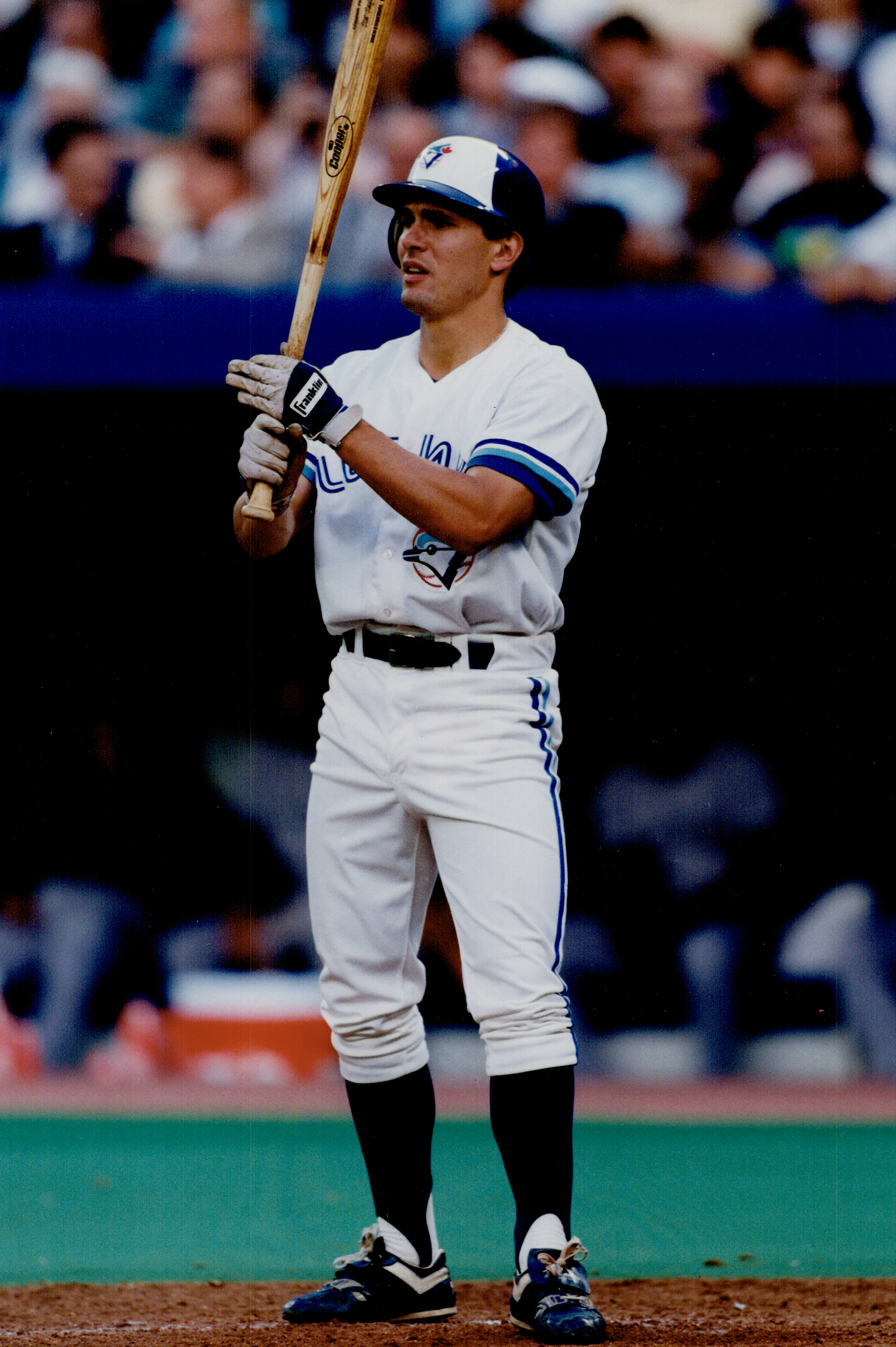

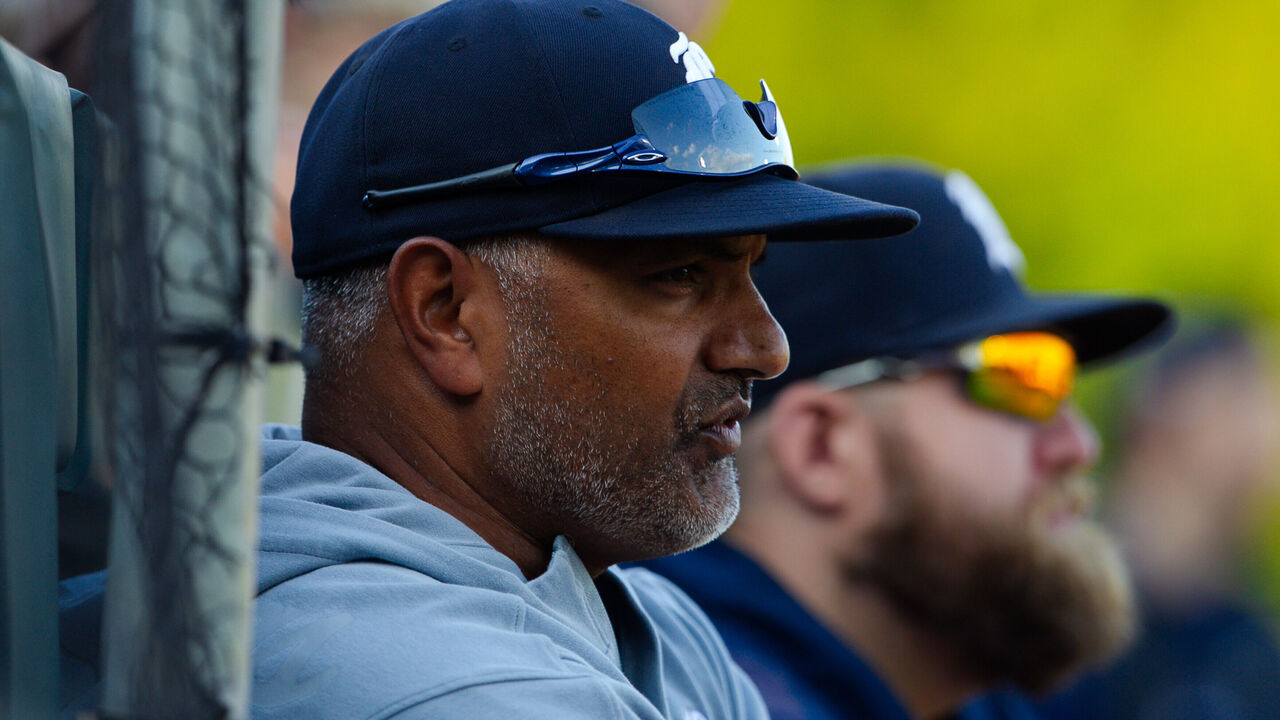

Rob Butler, the only Canadian in the Blue Jays' 1993 championship lineup, manages the IBL Toronto Maple Leafs (whose famous team name originated in baseball, not hockey). The air was warm and the vibe was relaxed when the Leafs visited Labatt Park a few Fridays ago. Boys played catch beside the infield as batting practice started. Children strolled to the home dugout to ask for fist bumps. Majors players skipped over the third-base line during pregame introductions, trailed at waist height onto the field by 9-year-olds from a local youth club.

Hitting leadoff at 7:49 p.m., Toronto's wiry shortstop stepped out of the batter's box on the first two pitches, intending to swing at neither offering. Hecklers ribbed him from behind the backstop.

There's no pitch clock in the IBL, but London's righty worked briskly on the mound. A high fastball induced a strikeout, eliciting whoops throughout the grandstand, to open the game.

London, population 422,324, is the largest city in Southwestern Ontario, the farm-rich area between the Windsor-Detroit border and the Golden Horseshoe megalopolis that rings Lake Ontario. Baseball gripped and charmed the people of this region before Canada became a country. In turn, they nurtured the pastime.

Players gathered on a pasture field in Beachville, Ontario, in 1838 to stage history's first recorded baseball game. A shoemaker sewed calfskin over twisted yarn to create the ball. One witness described the contest in writing, establishing that baseball existed before Abner Doubleday ostensibly invented the rules in Cooperstown, New York.

Swampland beside the Thames River was drained to construct Labatt Park. Christening it in 1877, a London pro club became the first champion of the International Association, a short-lived challenger to the National League. Rebuilt twice after floods, the park retained its distinction - despite objections from Massachusetts - as the world's oldest continuously operating baseball grounds.

History buffs know Babe Ruth clubbed his first pro home run in Toronto. Ruth pitched a shutout for the Double-A Providence Grays that same afternoon in 1914. Five years later, in the wake of world war and before the Bambino shimmered in the Bronx, the IBL materialized in four Ontario communities: Galt (now part of Cambridge), Guelph, Kitchener, and Stratford. The independent loop remains Canada's strongest baseball league after all this time.

Today, eight Intercounty teams play within driving distance of Toronto, Buffalo, and Detroit. A ninth team will launch next season in Chatham-Kent, Ontario, hometown of Ferguson Jenkins, the Cooperstown inductee and 1971 NL Cy Young winner who is the expansion franchise's honorary president. Identical statues of Jenkins, a Chicago Cubs icon, stand tall outside of Wrigley Field and Chatham-Kent's civic center.

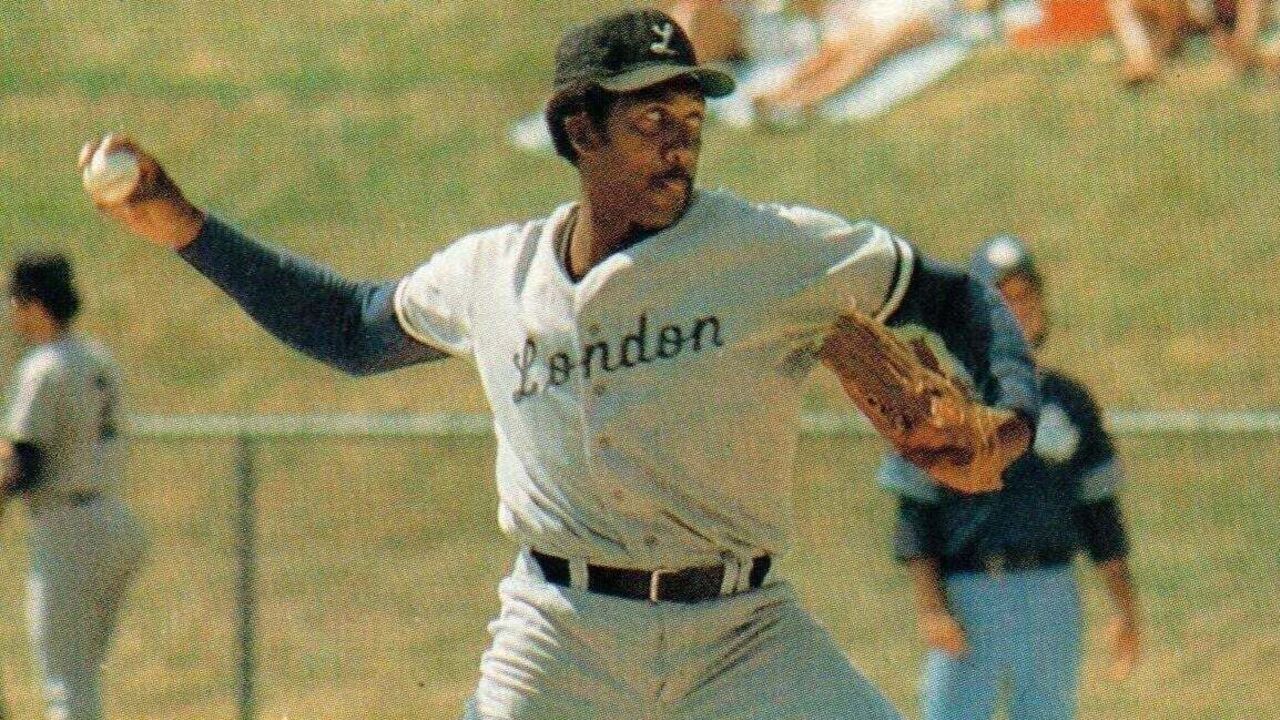

Since 1919, about 50 former major leaguers have graced IBL fields. One is Jenkins, who pitched for the Majors for two memorable summers as his career ebbed.

Jesse Orosco, MLB's career games-pitched leader, engraved trophies in a shop in Cambridge, Ontario, at 19 years old while playing by night for the defunct IBL Terriers. Former Blue Jays outfielder Dalton Pompey took the opposite route, hitting .381 for the Guelph Royals last season before he left baseball to become a police officer.

Raised in Toronto's east end, Butler overshot his wildest childhood dream by winning the World Series at home. He stroked a pinch-hit single against Curt Schilling in the '93 championship round. Stricken by a back fracture, Butler rehabbed the injury to play for the Maple Leafs alongside his younger brother Rich, another Blue Jays alumnus. Rob Butler batted .415 in the IBL from 2001-05.

"(The path I envisioned) was like: Play baseball in East York as a kid, play some junior ball, and then move on to the Maple Leafs," Butler said. "It was the pinnacle of baseball in Ontario. It's always been around in my life."

A seasoned junior coach, Butler rejoined the Leafs as manager this year. He said the caliber of competition wowed him: "There are so many electric players in the league." IBL lineups couple American, Caribbean, and Japanese imports - every team has four international roster slots - with college standouts who are home for the summer. Free agents get recruited to fill openings or email commissioner Ted Kalnins to express interest in signing.

"In many cases, they played in the minor leagues. Had a cup of tea in Double-A or whatever, and eventually you're released. They need a place to go," said Kalnins, a commercial litigation lawyer who used to pitch in the IBL for the Majors and Hamilton Cardinals.

"Some guys like me (eventually) decide: 'All right, fine, off to law.' But a lot of people want to keep playing with the hope of getting called back up at some point. We've had players get signed to free-agent contracts with major league teams. It's certainly not the norm or happens weekly. But it's a really good league."

IBL fields are eclectic. In Toronto, a grassy slope surrounds the Maple Leafs' home diamond at Christie Pits Park. Fans and passersby perch there to take in games for free. The team made money off hats, programs, and 50-50 tickets that Jack Dominico, the charismatic and tireless Leafs owner who died at 82 last year, hawked himself on the hillside on Sunday afternoons. (Following Dominico's passing, the franchise is for sale.)

"Christie Pits has always been this magical place with this magical aura," Butler said. "Anybody can walk down the street, sit on the hill, catch a game, and fall in love with the game."

In London, the downtown Kensington Bridge over the forks of the Thames River leads straight to 5,200-seat Labatt Park.

Named for a brewing family, the park's beer and food stands exclusively take cash. The diamond is symmetrical: Both foul lines span 330 feet. A huge net above the backstop prevents foul balls from landing on neighborhood houses and yards. Green trees and London's tallest buildings jut high above the chainlink outfield fence.

"It's situated so close to downtown. It's an old-time stadium that's well-kept. It's got a lot of history," said Majors manager Roop Chanderdat, who co-owns the team and led London to the IBL title in 2021 and 2022.

"I bring in guys from Japan, Puerto Rico, all over the world, and they always compliment the park."

Labatt Park used to host legends of the sport. Wagner's Pittsburgh Pirates and Cobb's Detroit Tigers traveled to face the London Tecumsehs, the city's first pro club, in exhibition clashes during the dead ball era. Barnstorming Black teams invited to play in London during the segregation era featured players such as Ferguson Jenkins Sr. - the Hall of Famer's father - and Paige, who made a three-inning cameo in 1954.

Future MLB stalwarts from Jeff Bagwell to Manny Ramirez to Jim Thome swung the bat at Labatt Park when Detroit made London its Double-A Eastern League affiliate from 1989-93.

Deion Sanders, center fielder for the '89 Albany-Colonie Yankees, went 4-for-4 at the plate in the Tigers' franchise opener. Rob Thomson, the Philadelphia Phillies manager from Ontario, began to climb the coaching ladder as an assistant to manager Chris Chambliss.

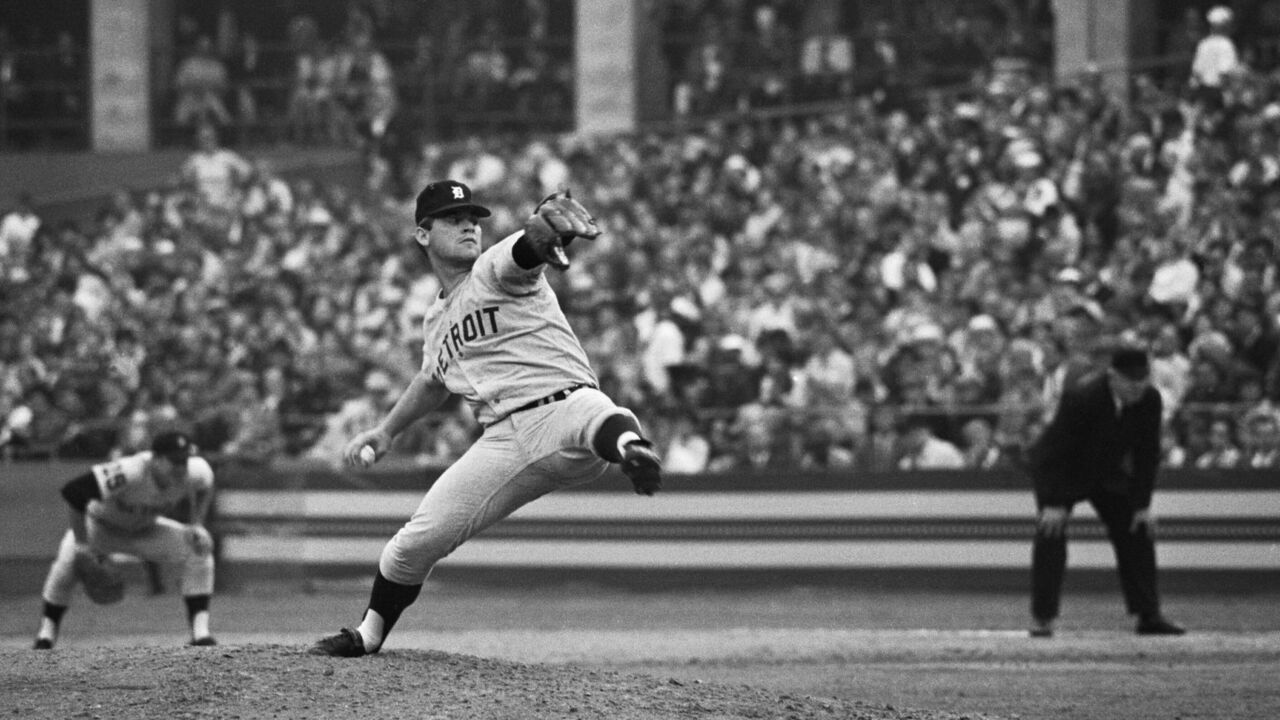

A few great Tigers suited up in London for the home team. Second baseman Charlie Gehringer was a Tecumseh in the 1920s before his Hall of Fame career got going. Denny McLain, the two-time American League Cy Young recipient, commuted by limo from his Michigan home to Labatt Park in 1974 to make 14 appearances for the Majors, manning first base and shortstop since his arm was shot.

An ace and a slugger anchored London's 1975 IBL championship team. Ex-Tigers hurler Mike Kilkenny dazzled with a 2.31 ERA. First baseman Larry Haggitt supplied the season's unforgettable moment. Haggitt walloped a homer that reached the Thames River bridge and crashed into the windshield of a moving car - his own, which his wife was driving to Labatt Park, as longtime Majors player-owner Arden Eddie once recounted in the team program.

Active in the IBL for more than 30 years, Eddie played with or against two-thirds of the league's all-time Top 100 players. He leveraged his cachet to persuade Jenkins, cut by the Cubs at 41 in 1984, to drive from Chatham on game days to throw for the Majors. Eddie enlivened Jenkins' IBL debut, slipping on the dewy grass near first base as a pop-up landed with a thud beside his head.

"Arden was more embarrassed than anything," recalled Alex McKay, London's second baseman at the time. "He said something like: 'Hey, welcome to the Intercounty, Fergie.' It wasn't a very auspicious debut for his first game. But it was fun to talk about later on."

McKay was destined from childhood to join the Majors. He graduated from bat boy to teenaged injury fill-in on the '75 title team. McKay played in London for his dad, Roy, who's second behind Chanderdat on the franchise's managerial wins leaderboard.

Born in 1933, Roy McKay's London upbringing equipped him for a baseball life, first as a minor-league southpaw in Georgia and later in the IBL. George "Mooney" Gibson, a Pirates catcher and manager who shared the field with Wagner, returned home to London in retirement. An early Majors manager, Bill Farquharson, found summer jobs in the local parks departments for U.S. college stars who generously taught kids the fundamentals.

"These are all people my dad knew of or would know to talk to about how to play the game," Alex McKay said. "When my dad played pro ball, he learned a lot. But he'd go: 'I was getting the same information, the same type of coaching,' from people he knew in London."

Bat-and-ball competitions trace back to ancient Egypt, but baseball popped up closer to London in 1838. Cedar sticks in hand, men from the farming village of Beachville faced a team from a neighboring township in the oldest contest on record.

The game was played June 4, a holiday to herald King George III's 100th birthday, on a smooth field behind the Beachville blacksmith's shop. A 7-year-old future physician named Adam Ford memorized the day's sights, terminology, and primitive rules. Ford detailed them in a very belated letter to the popular American newspaper Sporting Life.

The first of five bases, known in Beachville as "byes," was situated 18 feet from the batter's box to put more runners in play. Those who were hit with the calfskin ball while they navigated the basepaths were out. Batters who didn't swing at strikes were jeered, but onlookers enjoyed seeing "the mistakes of the fielders when some fleet-footed fellow would dodge the ball and come in home," Ford wrote to Sporting Life while residing in Denver in 1886.

Runs, called tallies, were counted by cutting a notch on the end of a stick, Ford's letter noted. His meticulous account of the game, transcribed by MLB official historian John Thorn on Medium, name-dropped most of Beachville's lineup: "I remember seeing Geo. Burdick, Reuben Martin, Adam Karn, Wm. Hutchinson, I. Van Alstine, and, I think, Peter Karn and some others."

Some historians question Ford's trustworthiness. He waited 48 years to recount this childhood memory in exhaustive detail. Ford was also a heavy drinker (and was accused of, though never tried for, murder by poisoning when he lived in Ontario). Speaking to Sportsnet in 2015, Thorn called Ford's recollection "preposterous on its face" and said the Beachville game ought to be viewed as a "pleasant legend, not as the first of anything."

Circumstantial evidence does support Ford's version of events, however. Land records reviewed by Robert Barney, a London sports historian, affirm that the blacksmith's shop and adjoining field existed in Beachville as Ford remembered. Tombstones bear the names and verify the lifespans of players mentioned in his letter.

#OnThisDay in 1838 baseball's first organised game was played... in Beachville, Ontario! This is *before* the alleged codification of the game by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown. A splendid bit of history! pic.twitter.com/KMertPf74W

— The SPORT Gallery (@TheSportGallery) June 4, 2023

Convinced the Beachville game happened, Canada has commemorated it on stamps and silver coins.

"There were certainly ballgames played on an informal basis in the United States and Canada before (1838)," Barney, dressed in old-timey baseball garb, told CBC when the game was re-enacted in Beachville on its 150th anniversary.

"This happens to be the first one of record - at least record that has been substantiated to any degree."

Baseball spread to London, which became a regional nexus of the sport. Garrisoned British soldiers played on their military reserve a few blocks east of the Thames River. Locals defeated a lineup from the nearby town of Delaware 34-33 in a lively two-inning encounter in 1856.

A settler from New York, Imperial Oil founder Jacob Englehart, bankrolled the pro Tecumsehs as they sought to keep pace with the regional powerhouse Guelph Maple Leafs. Star American recruits populated both rosters. Ace pitcher Fred Goldsmith, a trailblazing curveballer Englehart signed to a $100 monthly salary, sparked London to the inaugural International Association pennant. Bigger cities failed to measure up in the 1860s or '70s.

"Toronto was still playing cricket. Detroit was mucking around with very low-level ball," said baseball historian and author Brian "Chip" Martin, a retired London Free Press journalist whose books about the sport include a history of the Tecumsehs.

"If London or Guelph teams went to Toronto or Detroit to play a baseball game, they invariably trounced the opposition."

The London-Guelph rivalry was fierce, Martin said. Trainloads of fans followed the Tecumsehs and Leafs to either ballpark. Crowds sometimes outnumbered Guelph's population of 8,000. In 1876, hundreds of spectators miraculously survived the collapse of temporary bleachers erected in London's Victoria Park, the Tecumsehs' home on the former site of the British garrison.

"It was that sort of near-tragedy that prompted a local merchant to find the grounds that became Labatt Park at the forks of the Thames," Martin said.

The first game at Labatt Park, initially known as Tecumseh Park, predated by a year the Clinton, Massachusetts, opening of Fuller Field, a modest diamond briefly recognized by Guinness World Records as the oldest continuously operating ballpark worldwide.

Following an 1883 flood, home plate in London was moved away from the river to the west side of the grounds. To combat a Clinton historian's claims, London officials sent evidence to Guinness to show play was never interrupted and continued on the same field, the Telegram and Gazette newspaper reported to its Massachusetts readers in 2008.

Guinness certified Labatt Park's place in history that year.

"There's no question now, despite the claims of that little field in Massachusetts," Martin said, "that in fact Labatt Memorial Park in London is the oldest baseball field in the world."

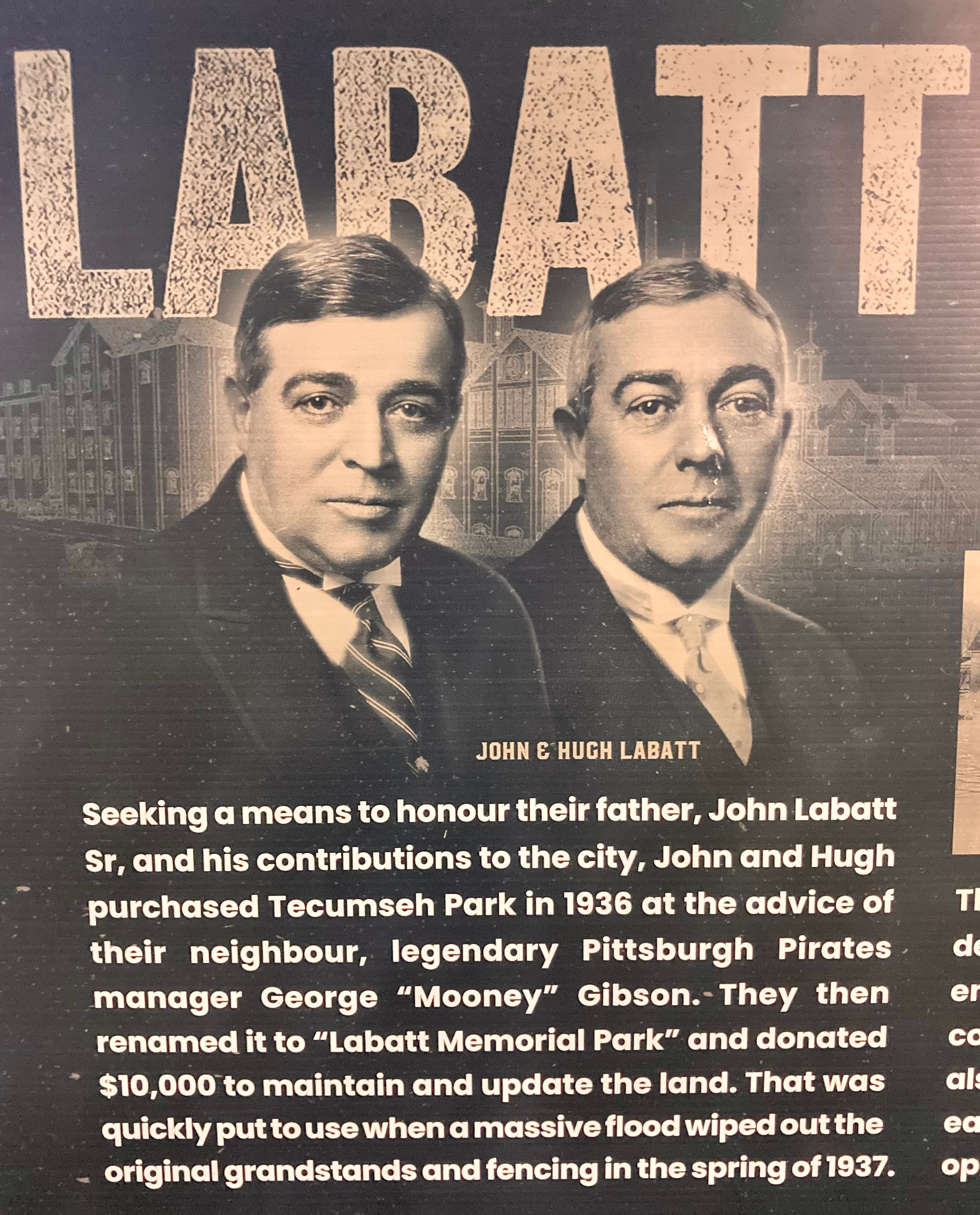

Maintaining continuous operations has demanded resilience. When a dozen feet of floodwater inundated the diamond and washed away the stands in 1937, the city restored the ballpark using $10,000 serendipitously donated months earlier by the London brewing magnates John and Hugh Labatt. The brothers received naming rights and a guarantee that the grounds would always house recreational activities.

Fans flocked to women's softball games at Labatt Park during the war years. COVID-19 kept them away in 2020. The pandemic nixed the IBL season, but Chanderdat organized a single Majors exhibition clash, hosting the Guelph Royals with the local health unit's consent to make sure the diamond didn't sit quiet all summer.

"I didn't want there to be doubt that the streak continued," Chanderdat said. "Whether it was a pandemic, a war, whatever - somehow, you've got to play a game there."

Dynasties have ruled the IBL this century. Beginning in 2006, Chanderdat's first season as Majors manager, the Brantford Red Sox clinched seven championships in eight years. The Barrie Baycats won six straight rings from 2014-19. Last season, the Majors defended the title in style, erasing a four-run deficit in the ninth inning of the decisive game to stun the Maple Leafs on the road at Christie Pits.

They headed home with the Dominico Trophy and invited fans to admire it at Labatt Park. Success is fleeting - London rebuilt and slipped to seventh in the IBL standings this season - but the field will be preserved, fulfilling what the Labatt brothers were assured.

"It's not going to be torn down tomorrow," Martin said. "Who knows how much longer we'll all be around, but it's going to be here."

A few Fridays ago in London, dozens of kids stormed through the Labatt Park concourse at top speed to receive a stamp of approval to run the bases between innings. Six college-aged hecklers sitting behind the plate got looser and louder as the night progressed. There were hits galore - 33 combined between the Majors and Maple Leafs.

London thumped Toronto 16-7, thanks partly to a storybook moment. Nine-year-olds from the local youth team willed dingers into existence. When the Majors loaded the bases on three singles in the second inning, they stood at the home dugout's rear railing and chanted, "Hit a home run! Hit a home run!" Complying, London's center fielder socked a grand slam over the wall.

The crowd erupted. The epic instrumental theme from "Superman" played over the loudspeakers. The slugger tapped helmets with the teammates he plated as the Majors' dugout emptied to mob him on the grass.

The chanting resumed later in the frame. London's catcher batted with a man on first and skied a deep shot to right field that disappeared behind the fence. The kids roared. The DJ blared the "Superman" theme. The Majors streamed onto the field as the sun set to celebrate again.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.