Why a good fastball is baseball's most important pitch

It is easy to get too cute when thinking about pitching. For all the attention given Masahiro Tankaka’s splitter and Jose Fernandez’s curveball and Stephen Strasburg’s change up, there is no substitute for a good fastball.

There is no one set way to attack hitters but a good fastball goes an awful long way. Without one, pitchers are at the mercy of hitters to expand their zone and go after bad pitches.

Velocity isn’t everything but it certainly helps. Even a pitcher without his “peak” velocity can still dominate using a well-place fastball.

The Master and Commander

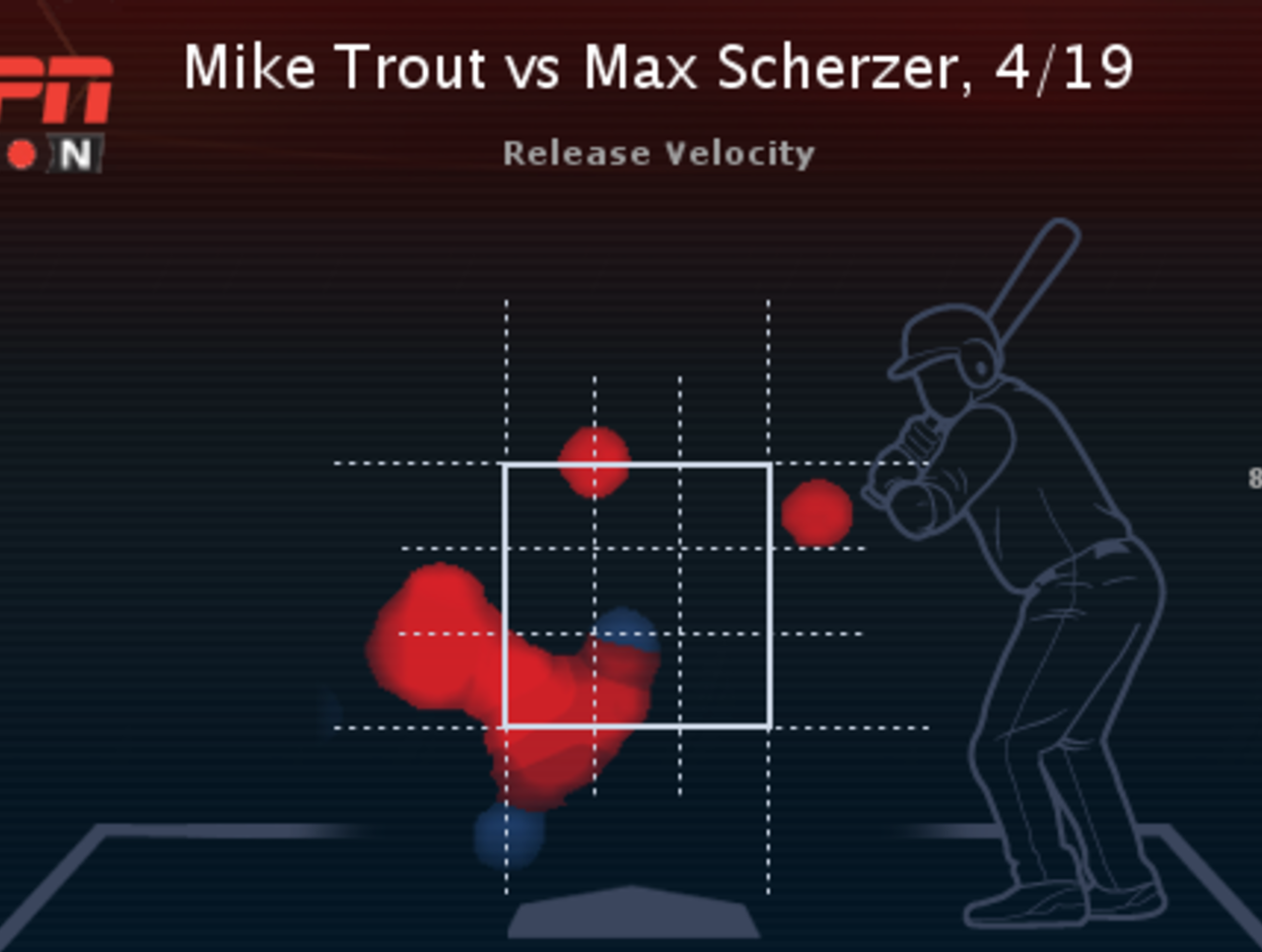

On Saturday afternoon, Max Scherzer did something only one other pitcher did before him – he struck out Mike Trout three times in one game. No Mike Trout isn’t immune to the K but of the 354 big league games he played, only Tom Milone struck him three times.

How did Max Scherzer do it? Was it his devastating slider or bravely throwing his fierce change up to an arm-side batter? As it turns out, it was the fastball that Scherzer used most effectively. Of the 14 pitches Scherzer threw Trout on Saturday, 10 were fastballs.

For most pitchers, throwing this much heat to Trout is a death sentence. But Scherzer’s fastball is no run-of-the-mill four seamer, thanks to his Cy Young-winning command. Against Trout, even when Scherzer missed with his fastball, it was just off the plate on the outside corner – eventually working back to that corner but getting a few calls in his favor. Nothing inside that the Angels’ outfielder can pull for power, despite a recent trend towards busting Trout inside.

Max Scherzer has plenty of time before the summer weather arrives to heat up his fastball velocity. Because of his incredible command and control, he can still challenge the best hitters in baseball with his fastball, knowing he can keep it out of harm’s way.

The Craftsman

Felix Hernandez is a great pitcher, one with some trophies in his palatial home just like Scherzer. Though they’re similar in age, King Felix is an old hand in the American League, notching 800 more innings than the player one year his senior.

Hernandez is a complete pitcher, which is a kind way of saying he gets by on more than just his fastball. The King is known for his hot starts, a feat some credit to his ability to throw any pitch in any count.

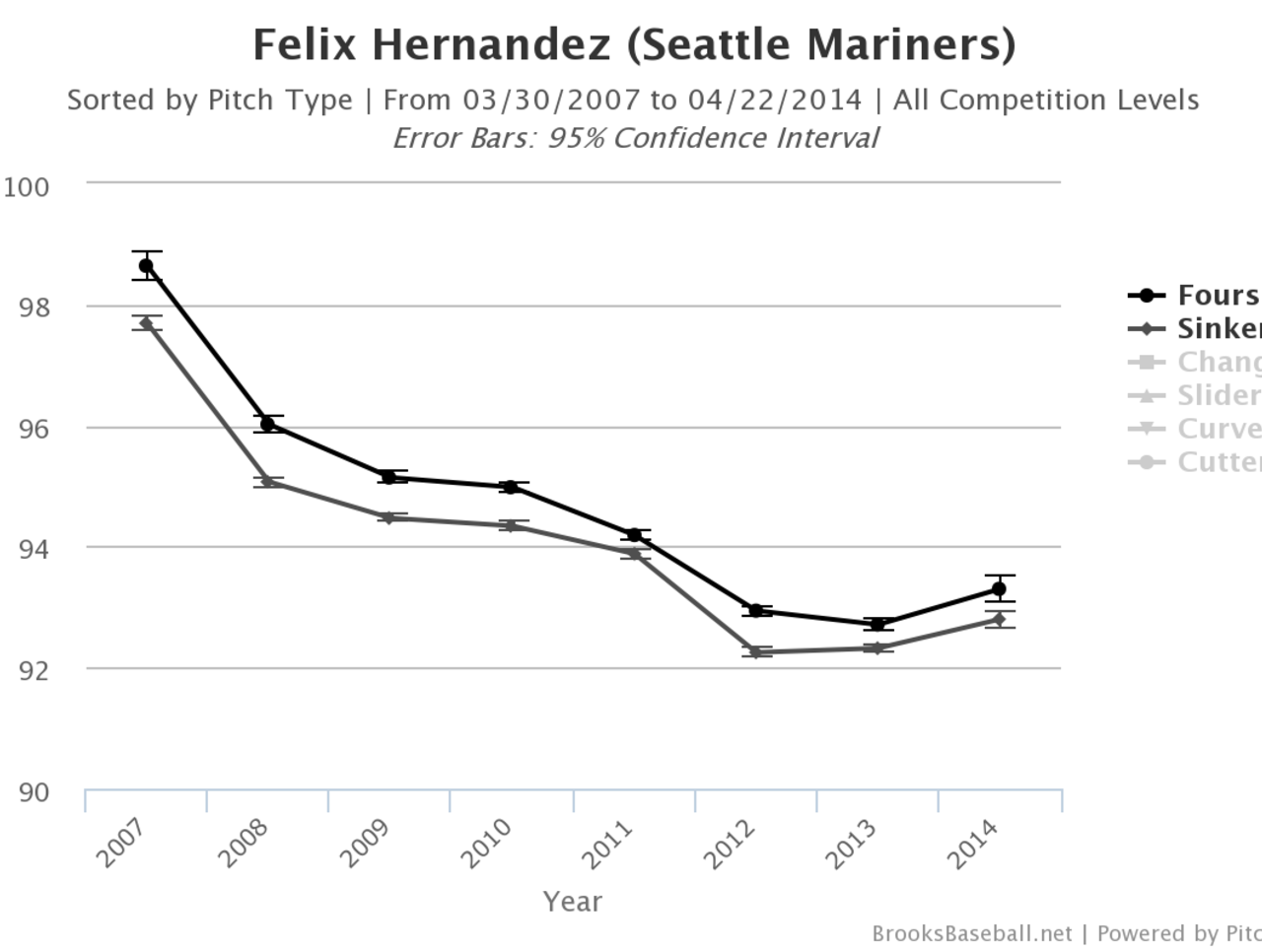

As his fastball velocity wanes, Felix relies more and more on his secondary pitches. But while his fastball velocity is in clear decline, it is still a great pitch.

At this stage of his career, Felix throws his fastball around 93-94 mph and his changeup around 90. Not at typical spread but Felix’s ability to spot his fastball and the immense movement of his change make it a deadly combination.

When Felix faced the aforementioned Trout on Opening Day, he followed a similar game plan to Scherzer - plenty of fastballs. Though Trout took Hernandez deep with a slider down in the zone, Felix stayed with hard stuff inside and finally struck him out later in the contest, alternating between his fastball and change.

So far in 2014, Felix works 1:1 with his fastball compared to everything else - more soft stuff than a man of his considerable means would seem to require. Because he can throw his fastball to both sides of the plate with an assortment of secondary pitches that would make a pitching coach cry, he gets to be Felix Hernandez. It’s good to the king.

The Desperate Soul

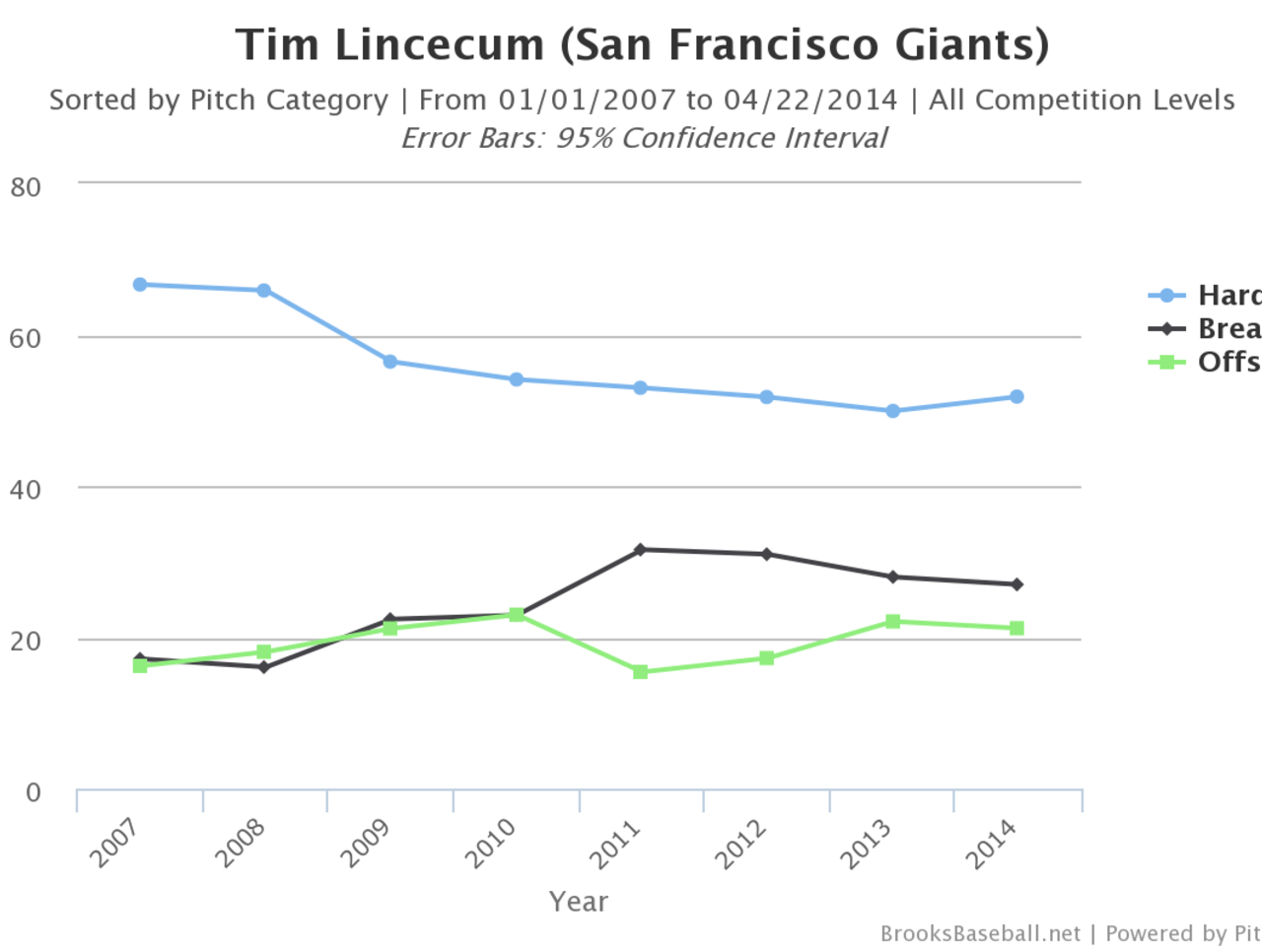

Tim Lincecum used to be like Felix Hernandez. Now he’s a shadow of his former self. The current edition of Tim Lincecum is a slop-tossing junk baller, living off the K and the hope that batters expand their zone.

To watch Tim Lincecum game-to-game is to observe a pitcher constantly at odds with his stuff, attempting to figure out which of his breaking balls will save his skin today. On Sunday, it was his curve/slider combination, a pitch he counted on for more strikes than his fastball, now with a little less zip and a lot less command.

Lincecum won two Cy Young awards of his own in 2008 and 2009. The Giants teeny righty was a different pitcher then, with much more juice on his fastball and a variety of devastating off-speed offerings. His fastball command was never “great” but his ability to make hitters swing and miss at his breaking stuff/change up made him great.

Despite sparking strikeout and walk numbers this year, Tim Lincecum owns a less than inspiring stat line. Batters claim a terrifying .314/.341/.593 against Lincecum, They’re hitting .419 against his fastball this season. The Giants hurler claims a 6.43 ERA even after a strong outing over the weekend.

Against most lineups, a pitcher without a fastball is a dead duck. The San Diego Padres, Lincecum’s opponents at Petco Park Sunday afternoon, are not most lineups, specifically young first baseman Tommy Medica.

Medica had a tough time against the Giants fourth starter, striking out in all three of his trips to the plate. It became abundantly clear that he had no answer for Timmy’s curve/slider combo, as SF’s catcher Buster Posey called for more and more of the offspeed stuff as the day progressed. From the Brooks Baseball “scouting” report on Medica:

Against Breaking Pitches (66 seen), he has had an exceptionally poor eye (-0.04 d’; 44% swing rate at pitches in the zone vs. 46% swing rate at pitches out of the zone) and a steady approach at the plate (0.12 c) with a disastrously high likelihood to swing and miss (50% whiff/swing).

If anyone on this earth was an ideal matchup for Tim Lincecum, it’s this poor kid.

Of the 14 pitches Medica saw, just six were fastballs. In the final at bat of the day, Lincecum threw Medica a slider with the count 2-1, then 3-1 and finally with a full count he froze the young Padre with a fastball over the heart of the plate (see 1:00 of the below video).

For Lincecum, the threat of his three good breaking balls makes his fastball barely passable, even if it is an ordinary pitch at this stage of his career. Few pitchers are as willing to to their soft stuff as freely as Lincecum, who features a 50/50 split between hard and soft.

But even his outstanding soft stuff cannot carry the huge load his limp fastball demands. His walks are way down this year but he’s just serving his fastball over the middle of the plate far too frequently - at most big league hitters won’t miss those.

Velocity is everything but it isn’t the only thing. As the baseball world marvels as Mark Buehrle cheats death around the margins of the strike zone, the ability to command the fastball is second to none. No pitcher can survive on junk alone, no matter how hard Tim Lincecum and others bleeding velo might try.

HEADLINES

- WBC Power Rankings: Can anyone prevent a USA-Japan rematch?

- U.S. shows offensive muscle in 15-1 win over Giants before WBC

- World Baseball Classic odds: Who will challenge Team USA?

- World Baseball Classic preview: Everything you need to know

- Report: Phillies' Rojas fails PED test, won't play in WBC for Dominicans