How the Cleveland Cavaliers nearly became the Toronto Towers

When the Cleveland Cavaliers won the NBA championship in 2016, a city whose identity had been defined by decades of heartbreak and disappointment finally - finally! - had something to celebrate.

Yet, even the most un-Cleveland moment in Cleveland sports history comes with a backstory that probably feels a bit too familiar to Clevelanders. The majority of basketball fans under age 35 might not know it, but the Cavaliers very nearly became the NBA's first Canadian franchise - a dozen years before the Raptors were born.

And while the Cavaliers remained in Cleveland - and ultimately delivered the city its first major professional sports title in more than 50 years - the image of then-owner Ted Stepien holding up the Toronto Towers logo, proud smile on his face, is a chilling sign of just how close the Cavs came to being a forgotten footnote in the NBA annals.

"He was dead serious," Kent Schneider, Stepien's close friend and lawyer, told theScore. "He was going to do it."

__________

(Photo courtesy: Getty Images)

Stepien purchased a majority share of the Cavaliers in 1980. At the time, he was best known for his advertising business, Nationwide Advertising, which had 35 offices across North America, including a branch office in Toronto.

Yet, while he enjoyed some success in the ad industry, the sports world presented an entirely different challenge - and he was comically ill-equipped for it. He showed little regard for the long-term viability of the team - and even less basketball acumen - when he approved transactions within a span of five months that saw the Cavaliers give up four years' worth of first-round picks (1983-86) for players who flamed out.

The four players taken with those first-round picks - Derek Harper (1983), Sam Perkins (1984), Detlef Schrempf (1985), and Roy Tarpley (1986) - combined to play more than 3,900 games in the NBA, while the players acquired in those trades - Mike Bratz, Richard Washington, Jerome Whitehead, and Geoff Huston - appeared in a combined 436 games with Cleveland. Huston was the only player to appear in more than 90 games with the Cavs.

The flurry of terrible moves forced then-NBA commissioner Larry O'Brien to put a moratorium on the Cavaliers, requiring them to obtain league approval before making any more moves. The league also instituted a rule preventing any team from trading first-round picks in consecutive seasons. "The Stepien Rule" still exists today.

By March 1983, when Stepien announced his intention to move the team to Toronto, the Cavaliers were wrapping up a three-year stretch in which they won just 66 games. That slump was highlighted by a 15-67 showing during a 1982-83 campaign in which they cycled through four head coaches - including Don Delaney, previously the head coach of Stepien's professional softball team.

Many who experienced the Stepien era up close tell a familiar story: He was an affable guy off the court, but was simply overwhelmed as an NBA owner.

Leo Roth covered the Cavaliers for The Lake County News-Herald in Willoughby, Ohio. Among his favorite memories: Stepien tossing softballs off the roof of the 52-story Terminal Tower during the building's 50th-anniversary celebration, damaging two cars and breaking an onlooker's wrist.

"He was a kind-hearted guy," Roth told theScore. "He meant well. For a guy who was so successful in the business world it just seemed like once he got into sports, the Midas touch left him. Everything he touched turned to stone."

Schneider was more direct in his assessment of Stepien.

"He's the worst owner in the history of professional sports," he said. "That's not a subjective opinion. That's objective opinion."

After losing millions of dollars and dealing with comically low attendance figures at the Richfield Coliseum, Stepien decided it was time for a change of scenery. Toronto presented the most appealing scenario for Stepien, who purported to have lined up several investors, ticket-sale guarantees, and support from local politicians.

The announcement of the Cavaliers move didn't come as a surprise to those who were around the team.

"It was always a threat," Roth said. "Whenever the media, fans, or the city got critical of him, that would be his threat. Ted was so unpredictable. He loved Cleveland and I don't think he wanted to do it. But I think he would have."

__________

(Photo courtesy: Getty Images)

While Canadian basketball is thriving in 2018 (thanks in no small part to the nationally beloved Raptors), that wasn't always the case.

The history of professional basketball in Toronto began with the Huskies, who played in the 1940s in the Basketball Association of America for one season before disbanding. In the 1970s, Ruby Richman, the former coach of Canada's national team, worked with Harold Ballard to relocate a team to Toronto without success. The Buffalo Braves also played 16 home games at Maple Leaf Gardens from 1971 to 1975.

Leo Rautins grew up in Toronto and was a high school star at St. Michael's College School. Having attended several of those Braves games in the 1970s, he saw the potential for his hometown to support an NBA franchise.

"There was a general interest that was only going to keep growing," Rautins said. "But I don't know how Ted's management would have affected that."

A year before Stepien's announcement, Rautins - then a star small forward with Syracuse - had a chance encounter with the owner in the stands at Varsity Arena in downtown Toronto while he was watching a Team Canada game.

"Hey, are we getting a team?" Rautins asked Stepien.

"We're working on it," he replied.

If Rautins didn't take him seriously at the time, he did a year later. Stepien didn't just unveil a team logo at the announcement. He had reached an agreement with Ballard, who owned the NHL's Maple Leafs, for the Toronto Towers to play at Maple Leaf Gardens. The plan was to start selling season tickets immediately after the Cavs finished their final season in Cleveland.

His obsession with making a splash wasn't new. In 1981, the Cavs tried to lure NBA legend Wilt Chamberlain out of retirement, offering him a deal in which he would only play home games. Chamberlain declined.

Stepien had another attention-grabbing plan for the team's move to Toronto. Rautins was finishing his senior season at Syracuse and would be eligible for the 1983 draft. The plan was to draft him and have a Canadian star play for the first NBA franchise in Canadian history.

"It would have been a dream come true," Rautins said. "I kept thinking about how unbelievable it would be to play at home."

While Rautins and basketball fans in Toronto might have been ecstatic, Schneider didn't share in the excitement. Stepien needed some help to keep his finances afloat, and while he did estimate a move to Toronto would help him generate $6 million of income in his first season, he was going to sell Nationwide Advertising and take the money to help his basketball franchise.

Schneider disagreed with the move.

"It had nothing to do with the issue of keeping basketball in Cleveland," he said. "It had to do with his financial well-being."

Schneider arranged a series of phone calls with Dick Watson, the lawyer who represented George and Gordon Gund. The brothers, who owned Richfield Coliseum, would eventually come to terms on a deal with Stepien to purchase Nationwide Advertising and the Cavaliers for $22 million. (Stepien initially rejected overtures from the Gunds, but changed his mind when the siblings increased their offer.) League owners also decided to award the Cavaliers first-round picks from 1983-1986 to help undo the damage Stepien had done.

Just like that, the Stepien era was over in Cleveland - and so, too, was the dream of an NBA franchise in Toronto, at least for the time being.

__________

(Photo courtesy: Fun While It Lasted)

While Toronto would need to wait 12 more years for its NBA franchise, the story of Stepien, Rautins, and professional basketball in Toronto didn't end with the sale of the Cavaliers.

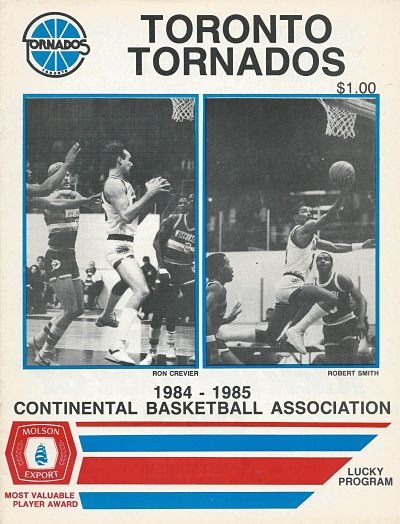

A month after selling the team, Stepien purchased a Toronto basketball franchise in the Continental Basketball League. The logo for the team, the Toronto Tornados, was almost an exact replica of the Toronto Towers logo, with the exception of some minor color changes and the removal of a reference to the CN Tower.

Rautins was drafted by the Philadelphia 76ers but was traded to the Indiana Pacers after an injury-filled rookie season. He then signed with the Atlanta Hawks but was let go after just four games in his second season. Without another NBA opportunity and upset at how his professional career was playing out, he got a call from Gerald Oliver, the head coach of the Toronto Tornados, with an offer to join the team.

The two sides went back and forth, but ultimately, Rautins' pride wouldn't allow him to come home to play for a CBA team.

"It wasn't the same thing as if there was an NBA team in Toronto," Rautins said. "I said no. I just couldn't play there."

Toronto's latest dalliance with pro basketball ended not long after it began. In 1985, the Tornados moved to Pensacola, Fla., unceremoniously ending Stepien's connection with professional basketball in Canada.

__________

(Photo courtesy: Getty Images)

Stepien passed away in 2007 at age 82. Schneider remembers his most famous client fondly, both professionally and as a close friend.

"He was a lawyer's dream. He created litigation in his wake. There was never a dull moment," Schneider said, adding, "There wasn't any pretense about him. He didn't care about fancy clothes, cars, or stuff like that even though he could have afforded anything. He was never pretentious."

Former NBA small forward Dave Magley, who might have been drafted by the Cavaliers for the sole purpose of a marketing campaign (he was briefly teammates with John Bagley, allowing Stepien to present them as "Bagley and Magley"), also remembers the former owner fondly.

"I really liked Ted," Magley told theScore. "He was a really interesting guy. He had a big personality. But unfortunately, he just didn't know enough about basketball and made a lot of goofy moves."

The near-relocation opens up plenty of hypotheticals, from whether the Raptors would've existed, to the possibility of LeBron James never playing in a Cleveland Cavaliers uniform, to the Cavs not ending the city's 52-year championship drought. But Schneider doesn't believe in opening that can of worms. Instead, he believes there would've been only one logical conclusion for the Toronto Towers: failure.

"It would have been a financial disaster," he said. "No matter how much money he got from the sale of Nationwide Advertising, he would have pissed it away in two or three years and ended up with nothing."

Alex Wong is a feature writer for theScore. His work has appeared in GQ, The New Yorker, Vice Sports, and The Atlantic, among other publications. Find him on Twitter @steven_lebron.

HEADLINES

- Portis: Bucks' recent hot stretch was 'fool's gold'

- Nuggets' Murray outduels George with 45-point outburst in win over Jazz

- Clippers rally from 17-point deficit to beat Warriors in Garland's debut

- Sengun, KD combine for 62 points to lift Rockets past Wizards

- Knueppel passes Flagg as Rookie of the Year favorite