The incredible tale of a hoops legend and his 99-point game

Radivoj Korac stood behind the makeshift foul line on the set of a Belgian talk show, 15 feet away from a hoop and perfectly at the intersection of who he was in life: basketball legend and man of the world.

It was late 1967. A few months had passed since Korac left his native Yugoslavia to sign with a team in Liege, a distant city of mostly French speakers whom he couldn't understand. For all the confidence he had to summon on the court to win seven Yugoslav League scoring titles, Korac was otherwise shy and humble; he could easily have let his dominance between the lines speak for him.

To Korac, and perhaps to Korac alone, though, half a season seemed plenty long enough to learn a new language. That summer and fall, he did, which is how he ended up on Belgian TV being asked to pinpoint the number of free throws he thought he could make out of 100. Korac, newly fluent in French but restrained in his estimate, said he'd be good for about 70 or 80.

As the studio backdrop retracted to reveal a basket, Korac dutifully stepped to the line in his street clothes and began to shoot granny-style, his trusted form. For the next while he lobbed attempt after underhand attempt toward the rim. When he finished, he'd hit all 100.

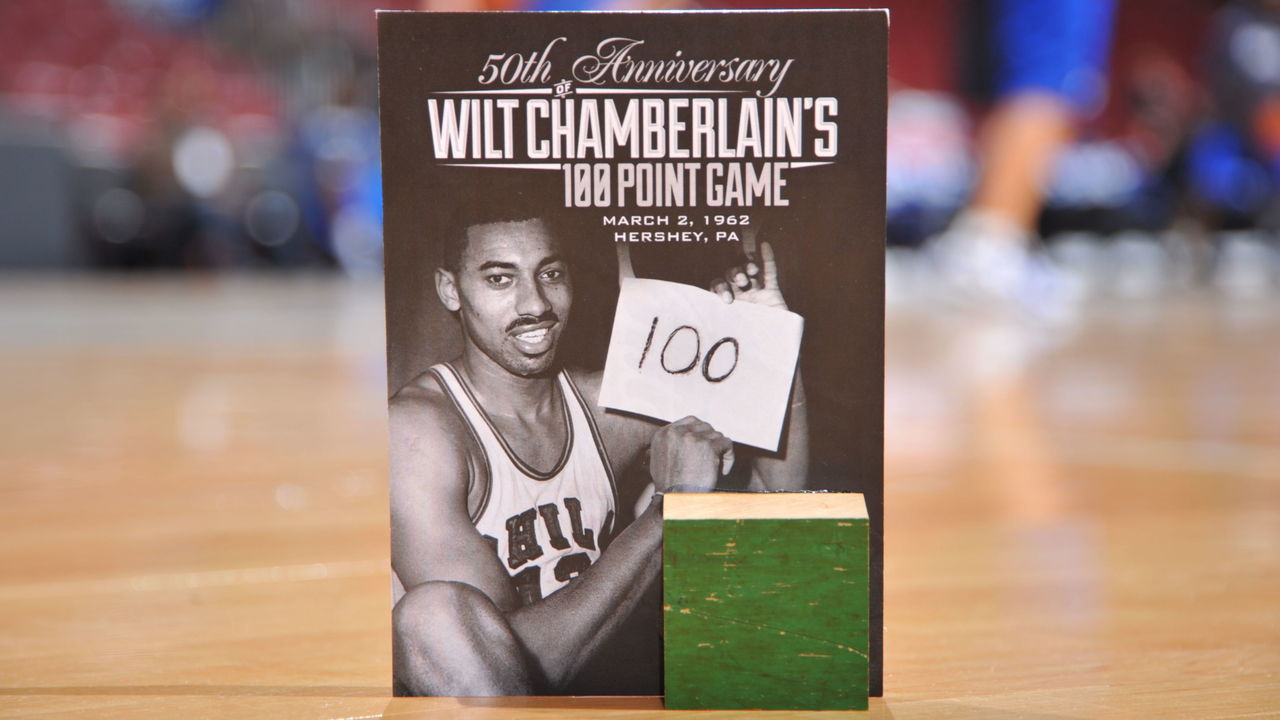

The thought of a player scoring 100 points occupies a fanciful place in basketball. No feat that has actually been done before seems less doable today. Only Wilt Chamberlain reached that hallowed, ludicrous mark in the NBA; he set his record on this day in 1962. J.J. Culver, the older brother of Minnesota Timberwolves rookie Jarrett Culver, dropped 100 in NAIA competition earlier this season, joining the small club of small-college stars who went off against teams so thoroughly incapable of containing them.

One wonders if Korac derived some extra satisfaction from his perfect streak at the charity stripe. His TV appearance didn't count for anything on a scoreboard, but it was a poetic epilogue to the single greatest game of his career, a performance not so much forgotten in North America as never properly appreciated.

Two years before he set off for Belgium, Korac parked himself in the post during a European playoff game and kept returning there to punish a helpless defense. His opponents, champions in their country, traveled two days by train to occupy the wrong side of history. Korac scored or drew fouls at will, play after play for 40 minutes, delighting a crowd that regarded him as a national icon, a brilliant player ascending in real time to his zenith. He was one point short of Wilt when the final buzzer sounded.

On the night Korac scored 99 points - among the most ever recorded in a high-level professional game - he was at home in Belgrade, the Yugoslavian capital. But the path he followed to that rarefied point was that of a globetrotter. As a younger man, Korac listened to The Beatles in London and outscored Oscar Robertson and Jerry West at the Rome Olympics. Long before Yugoslavia and, later, some of its constituent states became basketball powers, he guided his country at a tournament in Brazil to the first world medal it ever won.

Korac was born in 1938 in Sombor, the Serbian city that is also the hometown of Nikola Jokic. The parallel is apt. Korac never suited up in the NBA, but he was the best player on Yugoslavia's first golden generation of teams - a forerunner to the likes of Hall of Fame center Vlade Divac, and a nationally revered figure whose stature transcended his sport.

"He was a rock-and-roll star before rock and roll came to Yugoslavia," said Gordan Matic, the director of a 2011 biographical film about Korac.

Korac lived an eclectic and cultured life. On the subject of rock, he's said to have introduced Belgrade to The Beatles by gifting a local radio station a record he obtained during his travels to western Europe with the national team. Vladimir Stankovic, a basketball historian from Serbia, has written that Korac befriended artists, read Faulkner and Joyce, and frequented the theater and opera. He studied electrical engineering. He was good at chess.

Fittingly, he cut an unusual figure on the court. Short for a power forward at 6-foot-5, Korac often looked apathetic about the action around him when he didn't have the ball. That drab countenance concealed his extraordinary athleticism. Korac once proved in a high-jump contest that he could outleap his height. He soared above taller foes for rebounds and was strong enough to finish through contact, beating those defenders he couldn't outmuscle with his quick left-handed shot. Borislav Stankovic, who coached Korac with the Belgrade pro team OKK Beograd, described him many years later as "a scoring machine."

In the 1960s, Korac proved he could fill the bucket consistently - his career scoring average in Yugoslavia's top league was 32.7 points - and do so in marquee games. His 36 points in a comeback win over Peru started Yugoslavia down the path to a breakthrough silver medal at the 1963 world championship in Rio de Janeiro. Famed Spanish club Real Madrid hadn't lost at home in six years when, in 1964, Korac's 37 points paced a visiting international all-star lineup past the reigning European champs.

Korac led OKK Beograd to four Yugoslavian titles, the last of them in 1964. That victory qualified Beograd for the following season's European Champions Cup, a knockout event made up of two-legged series between the winners of the continent's dozens of domestic leagues.

Korac couldn't have started the tournament much better. On Jan. 7, 1965, he scored 71 points in a ransacking of the Swedish champions in Stockholm. Only in the light of what he did next would that astonishing figure seem modest.

Some context to know about Jan. 14, 1965, the night Korac took aim at Wilt's corner of history and very nearly got there: Alvik, the Swedish opponent in question, was no pushover. For eight years starting in 1964, Alvik won 169 consecutive games in domestic competition. Three of its players started for Sweden's national team. If OKK Beograd didn't employ a certain singular star, the Swedes might reasonably have hoped to hang close in the second of their playoff matchups.

Alvik lost by 98 points.

"It was not a very fun game, you know," said Alvik point guard Anders Gronlund.

Trouble trailed Alvik from the moment the team departed Stockholm by train for the second leg. The winding journey to Belgrade and back amounted to four full days of travel; Alvik was an amateur team, and work obligations precluded much of the roster from going away for so long. Only seven players wound up taking the trip, plus head coach Rolf Nygren, who activated himself on the lineup card to be ready to play in case of emergency.

Before the Beograd series, no member of Alvik's undermanned roster had faced a talent like Korac. Gronlund is now 76 years old, but particular scenes from the second leg in Belgrade remain with him. He remembers Korac flocking to the low block possession after possession, seeking out contact against two Alvik big men, Jorgen Hansson and Orjan Sviden, who simply weren't strong enough to challenge him. From the stands of Belgrade's sports hall, 3,000 exhilarated Yugoslavs cheered wildly.

It was incredible to witness up close, Gronlund said, but it got old quick: "You got tired of seeing him score."

Documentation of Korac's 99 points exists on an official scoresheet unearthed by Vladimir Stankovic, on which a scorekeeper recorded pertinent details from the game in pen. The sheet notes that tip-off time was 6:30 p.m. It shows that half the Alvik team - Hansson, Sviden, Gronlund, and Leif Bjorn - fouled out, forcing Alvik to finish the game with only four players, including Nygren, on the court.

The result was long settled by then because of Korac, whose personal scoring log is preserved on the scoresheet on a minute-by-minute basis. Minute 1: two points off free throws. Minute 3: a two-point field goal. Minutes 18 through 20: 11 straight points to end the first half, leaving him with 34 (to Alvik's 17) at the interval.

The scorekeeper's tracking system was primitive and laborious. You need to scrutinize the sheet to know that Korac had 62 points with 10 minutes left on the clock; 82 at the five-minute mark; 90 with two minutes to go. The limitations of the method lend credence to a prevailing belief about Korac's masterpiece: that as he crept increasingly, historically close to Wilt territory, not one person in the building knew precisely how many points he'd scored.

"Nobody knew he had 99," Stankovic told theScore. Only the scorekeeper had the information at his fingertips, and he wouldn't have had time to calculate the totality of Korac's output while the game was ongoing: "He just wrote, 'No. 5, two points. No. 5, two points.'"

No. 5 was Korac, and a close read of the scoresheet reveals the poignant truth each team would have learned after the game. Three dashes next to his jersey number, including one in the final minute, signify three free throws he missed out of 14 attempts. Making any one of them would have given the future Belgian TV marvel - the prolifically accurate underhanded shooter - 100 points.

| Final scores | Leg 1 (Jan. 7‚ 1965) | Leg 2 (Jan. 14‚ 1965) |

|---|---|---|

| OKK Beograd | 136 (Korac 71) | 155 (Korac 99) |

| Alvik | 90 | 57 |

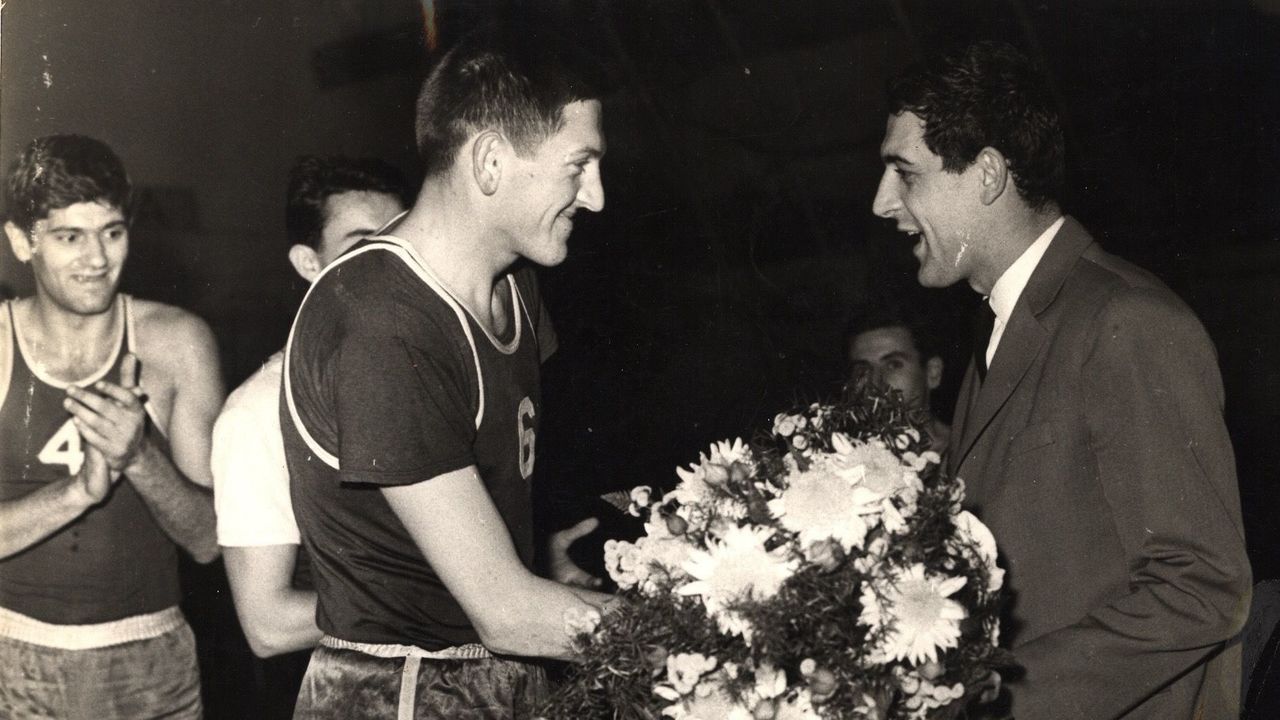

Instead, locked in at 99 and feeling characteristically humble, Korac shook hands with his opponents at the buzzer and told reporters postgame that ample credit for his production should go to his teammates. (One of them, fellow Yugoslavian national teamer Miodrag Nikolic, managed to score 32 points himself when he wasn't feeding the ball inside.)

Alvik, meanwhile, marked its exit from the European championship by embarking on the two-day trip home. Vivid in Gronlund's mind is the memory of squeezing onto a packed train out of Belgrade, every seat and sliver of space occupied except for the ground outside the washroom. Someone got his hands on a pack of cigarettes, and as they sat near a toilet for six hours, the players took turns exhausting its contents to mask the smell.

Korac had overwhelmed them, but at least there was something they could try to control.

"You're part of history," Gronlund said, referring now to how he feels about his role in Korac's famous game. "Obviously, it would be better to be the guy who scored 99."

Even after his brush with Wilt, Korac had superlative showings left to unleash before the European championship ended. OKK Beograd beat the Greek team AEK in the quarterfinals behind his 37 and 42 points. Real Madrid eliminated Beograd on aggregate in the semis, but only after Korac scored 56 in the second leg, a 113-96 win, to remind the Spaniards of his capabilities.

Greater accolades were to follow. Korac made the all-tournament team when Yugoslavia placed second at the 1967 world championship in Uruguay. Soon after, he left Beograd for Belgium, where in 1968 he spurred Standard Liege to the club's first national title. He and Yugoslavia won silver at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. Then Korac jumped for a season to Italy's top division; he led the league in scoring and, as he did at Liege, learned the native tongue in months.

On June 2, 1969, Korac awoke in Sarajevo after starring for Yugoslavia in an exhibition game the previous night. He ate breakfast and set out for the five-hour drive back to Belgrade, where it's thought that he planned to attend the premiere of a musical. Several miles outside Sarajevo, he tried to pass a car on a single-lane road. He crashed into an oncoming truck.

Korac was 30 when he died. Thousands of people - among them members of the national team, teammates from his Italian club, and Vladimir Stankovic - filled Sarajevo's streets the following day to mourn his loss. The congregation stretched longer than a mile. Korac's father, Bogdan, accompanied his son's body home to Belgrade, where No. 5 was buried in a prominent cemetery's Alley of Distinguished Citizens, the first athlete laid to rest there among national luminaries.

Tributes to Korac abounded. Yugoslavia's basketball federation decreed that no more games would be played in the country on June 2. Teams, tournaments, and a street in Belgrade were named in his honor. OKK Beograd displayed his jersey and shoes in an exhibit at team headquarters. In 1991, FIBA named Korac one of its 50 greatest players; in 2007, he joined the FIBA Hall of Fame as part of its first class of inductees.

Matic, the filmmaker, released his Korac biopic in 2011, drawing on dramatized reenactments of highlights of Korac's life and interviews he conducted with former teammates, rivals, friends, and family. A few weeks ago, he answered the phone at his office in Belgrade to reflect on his subject's legacy.

"You can be a good student and good at basketball and a good person," Matic said. "You can have a positive influence on our society."

Twenty years after Korac's 99-point game, two Yugoslavian players broke through to reach the milestone that had barely eluded him. In a Yugoslav League game played on Oct. 5, 1985, the future NBA star Drazen Petrovic hit 10 threes - benefiting from a rule recently introduced across Europe - en route to scoring 112 points. Petrovic stood alone above the century mark for all of five days. On Oct. 10, Zdenko Babic went off for 144.

Fans of Babic's team, KK Zadar, valued this achievement for its staggering merit, but also for its practical implications. Babic led Zadar to the next round of a European knockout tournament, propelling the club one step further along in the Radivoj Korac Cup.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.