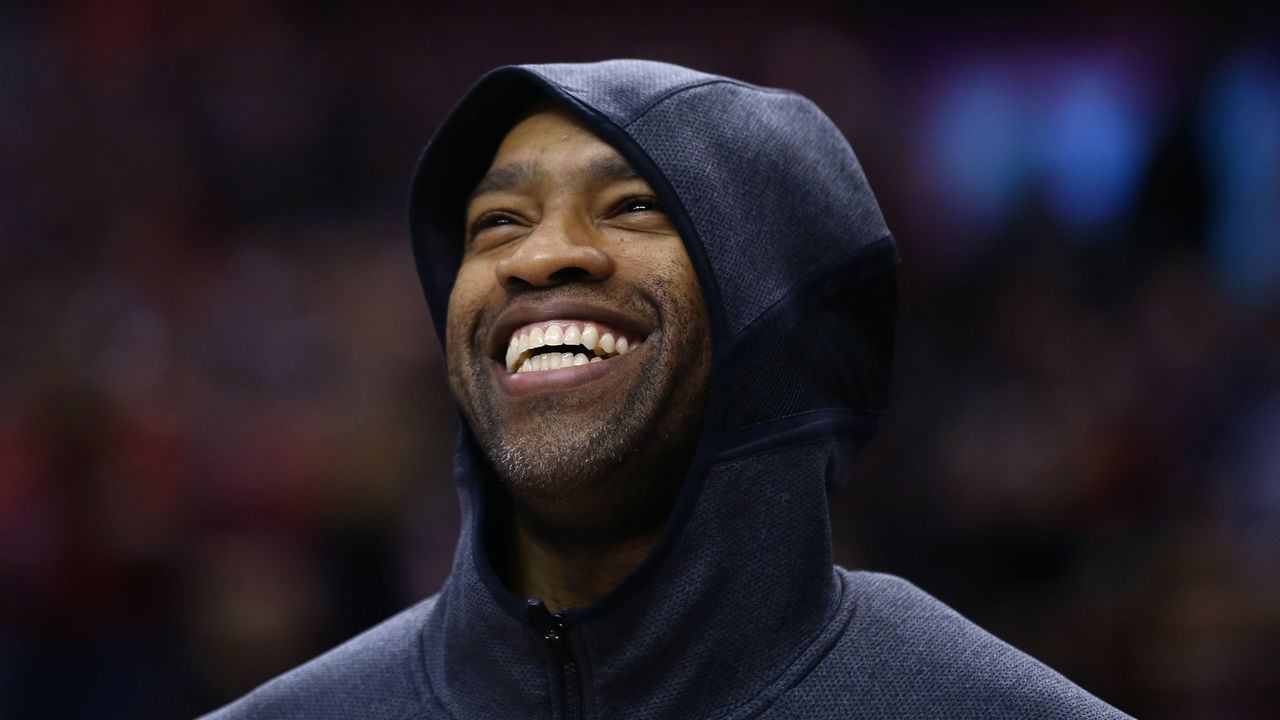

Vince Carter showed that there's grace in sticking around

By now you know how it ended. A 43-year-old Vince Carter, having announced before the start of the 2019-20 season that it would be his last as an NBA player, was sitting on the Atlanta Hawks' bench at the tail end of an overtime loss to the New York Knicks on March 11 when the league announced it was suspending its season because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As murmurs of the suspension spread throughout State Farm Arena in Atlanta, Hawks coach Lloyd Pierce, struck by a bolt of intuition (and some fans chanting "We want Vince!"), told Carter to head to the scorer's table. Carter checked into the game with 19 seconds to play, as the home fans, recognizing the moment for what it might've been, rose to their feet. Six seconds later, he stepped into a 26-footer and drilled it.

With the NBA officially approving a return-to-play plan that excludes the Hawks from the remainder of the season, we can now say for certain: that was the last shot of Carter's distinguished, prolific career.

What a strange and wondrous journey it was. Carter played for eight teams, authored some iconic moments, scored more than 25,000 points, and should be a lock for the Hall of Fame. His legacy will largely be defined by his early years: by the athletic fluidity and high-flying acrobatics that made him arguably the greatest in-game dunker we've seen; the galvanizing effect he had on basketball in Canada (to which the current crop of Canadian NBA players who grew up idolizing him are a testament); that dunk contest in 2000; the epic second-round duel with Allen Iverson in 2001; his fall from grace and ugly divorce with the Raptors; and his rejuvenation with the Nets.

Oddly enough, though, I think the parts of his career I'll remember most fondly are the last several seasons in which he toiled in comparative obscurity as a 17-minute-a-game vet for lottery teams.

A lot of the touchstones of Carter's NBA tenure were about agency. His decision to attend his graduation ceremony in North Carolina on the day of Game 7 in that 2001 series against the Sixers - and his missed game-winning attempt at the buzzer a few hours later - was still being litigated nearly two decades after the fact.

There were conflicting stories about how things managed to turn so sour during the end of his Raptors tenure, and who was most at fault, but the situation ultimately came down to Carter exerting his influence and holding the franchise hostage until he got what he wanted - a maneuver that likely wouldn't have felt as out of place in today's superstar empowerment era.

By the end of his time in Toronto, he was plainly dogging it. The fan base turned on him, hard. He was accused of exaggerating injuries. At one point, he insisted he wasn't going to dunk anymore. He allegedly got into a physical altercation with coach Sam Mitchell. Eventually, he went so far as to tip off opponents to the Raptors' plays. All of which looked worse when he immediately reverted to playing like his best self after being traded to New Jersey, and then admitted in an interview with John Thompson in 2005 that he hadn't pushed himself as hard as he could have during his latter Toronto years. (Though it's not like he was saying anything Raptors fans didn't already firmly believe. If he'd said otherwise, they'd have called him a quitter and a liar.)

Even as he reapplied himself with the Nets and answered questions about his durability, he was dogged by claims that he didn't work hard enough, or love the game enough, or respect his own talent enough. The thing is, Carter never seemed to want for himself what others wanted for him, or to be what others tried to make him into. Even as his staggering physical gifts and aesthetically seductive game made him a natural superstar, he seemed to shy away from that designation. He seemed happier and more comfortable as a role player in his twilight years than he ever did as one of the faces of the league.

For a while, he seemed like a passenger in his own narrative vehicle. People made him the hero and he played the part, for a little bit. They made him the villain and he played that part, too. (Played it damn well, as Raptors fans can attest.) Somewhere along the way he grabbed the wheel. Time passed, old wounds healed, and eventually the labels didn't matter anymore. He was onto his third team, then fourth, then fifth. He was an entirely different player, and, at least to the outside observer, a different person. Eventually he was just Vince: good-natured dude, sage veteran, great teammate, subsumer of ego, lover of basketball.

The agency he once wielded to force his way out of Toronto was channeled toward doing whatever it took to keep playing, and keep playing, and keep playing. That required him not only to work tirelessly on maintaining his body, but to continually conform to his new physical realities as he transitioned from star to complementary player to grizzled mentor. That's a transition not many high-profile players have been able to stomach, certainly not for as long as Carter did. But he was never too proud to adapt. And in his quadragenarian years, he still threw down the odd windmill dunk in the layup line to remind us he still had the juice.

Finally, after making the choice time and again to continue his playing career, he had it cut short because of the most unforeseeable of circumstances. But there was something fitting about the conclusion all the same. Credit Pierce for recognizing it might be Carter's last chance to do something in an NBA game, and Carter for making the most of it by immediately taking, and making, the shot that would be his last. The only piece of meaningful business that remained would have been Carter's final game in Toronto, which has become a far more forgiving and welcoming and celebratory place for him in recent years. Alas, as far as closure goes, that shot in Atlanta will have to suffice.

As Carter exits, I find myself thinking a lot about the finale of "The Good Place," which imagined a universe in which people were granted the ability to opt into or out of existence on their own timetables and their own terms. Envisioning finality as a choice didn't completely remove the melancholy from it - all endings are sad, even when they're past due - but it did add a tinge of satisfaction, a feeling of completeness that comes with seeing something through to its natural conclusion; what one character described as "a quietude of the soul." Nothing lasts forever, and we wouldn't really want it to. What we do want, I think, is to decide for ourselves when our journey's run its course.

That isn't how things work in reality, as far as we know. For pro athletes, retirement is framed as a choice, but in most cases their bodies make the choice for them. Some are able to make their peace with that reality better than others. Carter has done it more gracefully than most. Even if he didn't quite get to go out on his own terms, I like to think that as he watched that last 3-ball drop, he felt a quietude in his soul.

For him to have even arrived at this point would've once been inconceivable. Here was a player who thrived on effortless athleticism, whose commitment level waxed and waned early in his career, and who purportedly didn't work as diligently as his most accomplished contemporaries. If you were to sketch a portrait of a player whose comedown would be swift and decisive, it would look a lot like a young Vince Carter.

Our relationships to athletes often change as they get older. There's a sentimental pull for them to play on and keep succeeding. In part because of the comforts of constancy, in part because vulnerability tends to unlock a softer side of people, and in part because the career of an athlete is like a lifespan in miniature - from rookie season to retirement press conference, first steps to last words - so when one of them defies the aging curve it feels like a win for all of us.

As Carter aged, and the context and tenor of his returns to Toronto changed, those early days somehow felt closer, not further away. The joy and appreciation was back. He was celebrated the way he used to be, the way he always would've been had his tenure not ended so acrimoniously. Carter's perception of himself seemed to evolve over time, and our perception of him evolved along with it. He didn't craft the kind of postseason resume we typically associate with legends, but he lived an NBA life.

Carter somehow managed to avoid the depressing part of his physical decline, even as he trudged on for 13 years after his last All-Star berth, even as he played out the string on dismal, going-nowhere teams for whom his on-court services were largely perfunctory. Maybe that's because he himself never seemed at all embarrassed by it. He never seemed, in those later years, to be trying to prove anything, or to be desperately clinging to any particular idea of himself. He eschewed late-career ring-chasing, instead opting to sign with rebuilding outfits where he could mentor young players while actually getting some minutes outside of garbage time. His farewell tour was less about pageantry than quiet dignity.

It never felt like he was hanging on too long because no one ever seemed to get tired of having him around. And isn't that what we all want: to linger as long as we please without becoming a burden to others? Carter became a walking rebuke to the idea that it's better to burn out than to fade away. A guy who was once known for his fragility and lack of passion for basketball wound up being the longest-tenured player in NBA history. Twenty-two seasons, 1,629 regular-season and playoff games, spread across four different decades. Go figure.

"It's just, I loved playing basketball," he told Sports Illustrated's Chris Mannix shortly after his last game. "And 20-something years later it’s the same approach - I love playing basketball. So to really see and be appreciated and everybody just on the same page now. It's a great feeling. And it just makes it easier to walk out of the door."

There are any number of lessons one can choose to take from Carter's career. For me, the lessons are about aging gracefully, and about the subtle power of sticking around. Vince outgrew his labels, reinvented his game, and bent the long arc of his career in the direction that suited him best. He didn't go out as a hero, or as a villain. He didn't go out on top, but he didn't overstay his welcome, either. He did something far more nuanced than all that. He stuck around long enough to make us see him the way he always wanted to be seen. He stuck around long enough to let us watch him become himself.

HEADLINES

- LeBron breaks Kareem's NBA record for career field goals

- Wemby drops 38 points to help Spurs sweep season series with Pistons

- Trae brings plenty of excitement to court in Wizards debut

- How does Tatum's return fit into Celtics' storybook season?

- 6 biggest storylines to watch as NBA season enters stretch run