HBCUs seek to connect their storied pasts to a revitalized future

Before Kenny Blakeney and Mike Brey became Division I basketball coaches, they graduated from the same high school, DeMatha Catholic in Maryland. Brey used to run the JV squad at this hoops powerhouse, and he also taught American history for six classes a day. When Blakeney got in touch last offseason to pitch an idea, he knew Brey would understand its purpose, potential, and merit beyond the court.

The idea was this: On Jan. 18, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Brey's Notre Dame Fighting Irish would visit Howard University in D.C. to squeeze a nationally televised, non-conference road game into the thick of their ACC schedule. Blakeney is Howard's head coach and a D.C. native. If pandemic protocols allowed, he envisioned his opponents touring the King memorial, the site of King's "I Have a Dream" speech, and the national Black history museum a mile away. At minimum, they'd spend hours on campus, taking in the tradition and culture of a historically Black college.

"It's the plan to try to bring a Power 5 school to Howard every year," Blakeney said in a recent interview. "Hopefully, we can have multiple teams that come to Howard and play us and have a chance to witness - (as) an HBCU, as a university that means so much to so many people - who we are and what we do."

Little went according to plan for Blakeney and Howard in 2020-21. The past tense already applies because their basketball season is over, abandoned earlier in February due to COVID-19 outbreaks in and around the program. In all, the Bison got five games in - none since Dec. 18, including the scrapped Notre Dame game - and finished with a record of 1-4. Between March 10-13, the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (MEAC) is scheduled to crown a champion without them.

Two days after the Notre Dame game was to be played, Howard alumna Kamala Harris was sworn in as vice president of the United States. Howard was founded to help educate and empower America's Black populace in the wake of the Civil War. One lost basketball season is a speck in 154 years of fulfilling this pursuit.

Still, Bison fans could be excused for wondering what might have been this year, if only they played on King's holiday and got to showcase Makur Maker - the five-star recruit who chose Howard over bigger schools - to a national audience.

Racism is a foundational American sin. The country split in two to fight a war over Black enslavement, and the brutalization of Black Americans hit another inflection point in 2020. Police shot Breonna Taylor at home and suffocated George Floyd on camera in the street. A protest movement swelled to denounce their killings, demanding justice, accountability, and recognition that Black lives matter.

The movement continued to permeate sports, including basketball and football, and helped prompt resurgent interest in historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). NBA stars posted words of encouragement when Mikey Williams, one of the best 16-year-old guards out there, pondered on social media the idea he could attend such a school. That was last June, and by early July, Maker had declined several Power 5 offers to take his pro-caliber talents to Howard.

The 6-foot-11 Maker is South Sudanese, was born in Kenya, grew up in Australia, and lived in Canada for a time as a teenager. As he tweeted last summer, he wanted to make an HBCU his next home "so that others will follow."

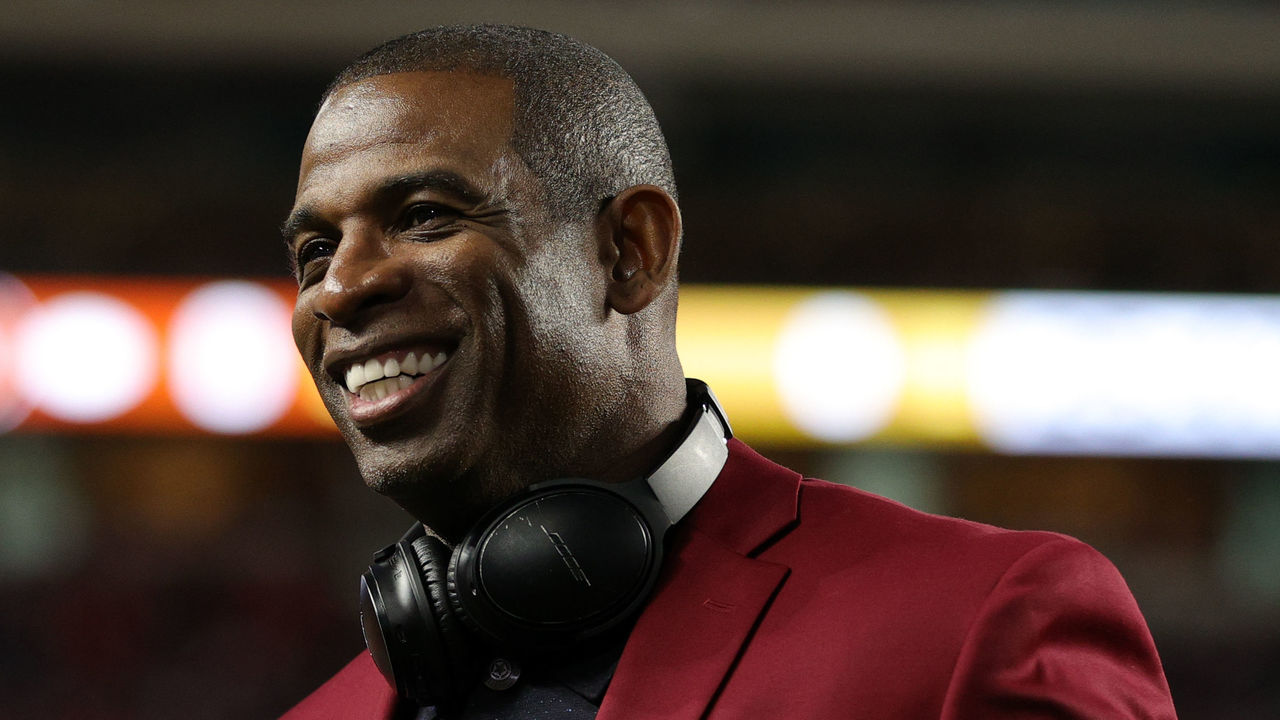

Maker sounded a bit like Deion Sanders did when he introduced his agenda for change at Jackson State. In January, at his first media day after accepting the job as the Tigers' head football coach, the Hall of Fame cornerback spoke literally and figuratively when he brought up the uneven playing field for the school, which is located in the Mississippi capital. Subpar equipment and resources keep players from thinking they can go pro, Sanders said. Still, he went on to land the strongest recruiting class in recent Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC) history, poaching transfers from the likes of Florida State and USC as he set about trying to reshape the NCAA landscape.

Delayed by the coronavirus, the SWAC's 2021 spring football season is now underway, and the excitement that surrounds Jackson State stands in contrast to Howard basketball's dampened spirits. After hurting his groin in preseason, Maker played a mere 48 minutes for the Bison during the team's first two games. He didn't dress the rest of the fall, got COVID-19 in January, and now has the option to leave Howard to enter the NBA draft. (His cousin, Thon Maker, is a five-year NBA vet.)

No matter what Maker decides, many more people will continue working to uphold the project he and Sanders have championed. Sports factor prominently into how HBCUs have uplifted Black students from emancipation through segregation and the decades since. HBCUs once springboarded scores of Black athletes to Hall of Fame careers; for instance, Mississippi Valley State, an early opponent on Jackson State's SWAC schedule, is the alma mater of Jerry Rice.

The modern HBCU is severely underfunded and, compared to the glory days and to Division I juggernauts, its record of sending players to the NBA and NFL is vanishingly thin. Revitalizing these schools' athletic programs might start with a few big-name commitments. It'll also require money; a broader, lasting attitudinal shift; and a full understanding of how HBCUs influenced generations of students and coaches.

Consider Robert Covington, the NBA's only active HBCU alumnus, whose sports science professors at Tennessee State marched alongside King in the 1960s. Consider Mo'ne Davis, the young woman who garnered so much attention at the 2014 Little League World Series and now is a softball infielder at Hampton. Consider Mo Williams, LeBron James' former sidekick, who's launched his college coaching career at Alabama State. Consider Doug Williams and James Harris, retired NFL quarterbacks who created the Black College Football Hall of Fame to memorialize a rich legacy.

These days, HBCUs are known for their marching bands and buoyant Homecoming weekends. To the first point: the NBA, which is donating money to HBCUs via next weekend's All-Star Game, tapped Grambling State and Florida A&M's bands to perform during the game's player introductions.

On the court and gridiron, these schools no longer have the same high reputation. If HBCU programs can build on the momentum of 2020, the hope is they'll be able to sustain it, so long as recruits can be persuaded to keep them in mind.

"HBCUs have been doing the work that so many brands and philanthropists and celebrities are just now starting to do. They've been there. Pouring back into communities and trying to uplift Black and brown people, that's what they've been doing since their founding," said Jasmine Gurley, the co-founder of HBCU Jump, an advocacy group that formed last June in the midst of the nationwide protests for racial justice.

Gurley added: "HBCUs are rooted in legacy. When these students are making these decisions, I always tell them to consider their legacy. Where can you have the most impact that lives beyond your four years? Who can you inspire to make new and different decisions that break the status quo?"

Following the Civil War, HBCUs became "the bedrock for Black citizens to create their own political, professional, and educational halls as a means of survival," Tyler Tynes once wrote for The Ringer. They created football teams, too. In 1892, Biddle University beat North Carolina rival Livingstone College 4-0 - one touchdown under the scoring system of the age - in the first matchup between Black colleges. Barred from enrolling in white schools, Black players found space elsewhere to flourish.

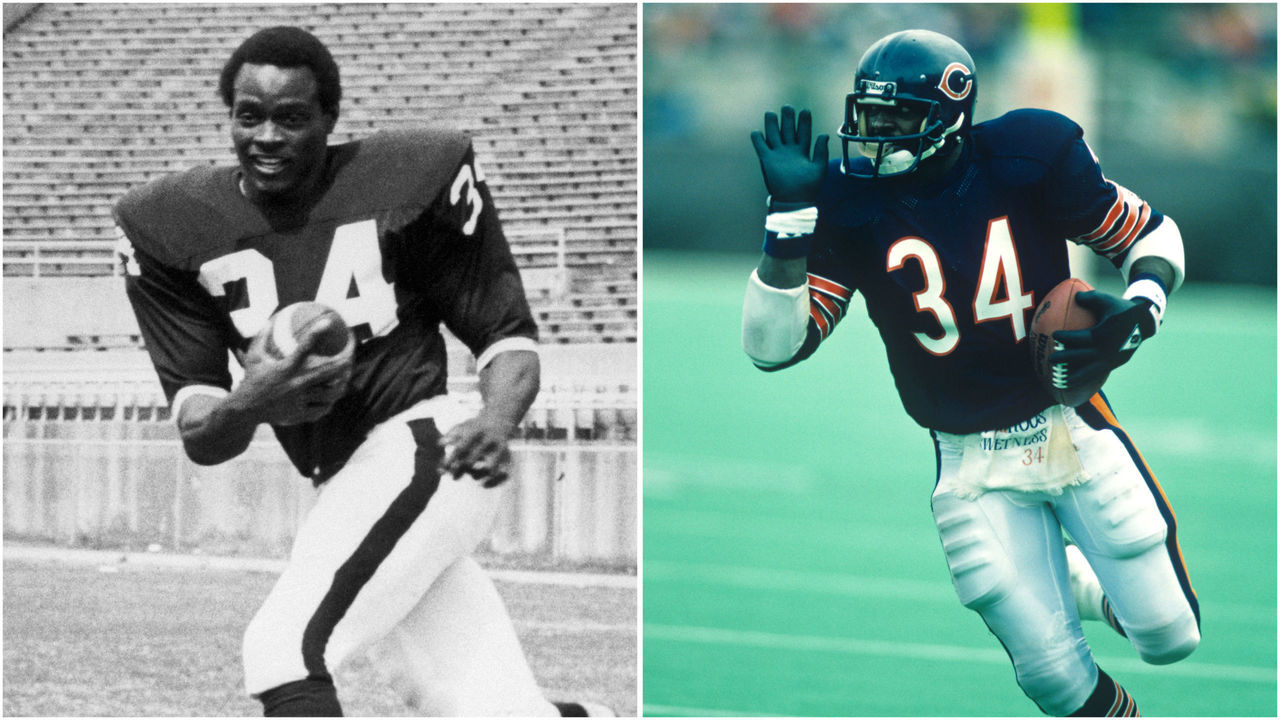

HBCU football excellence peaked in the mid-20th century, spanning the college careers of Willie Davis (Grambling State), Deacon Jones (Mississippi Valley State), Mel Blount (Southern), and Walter Payton (Jackson State). Bolstered by a recruiting monopoly, these elite programs in turn helped strengthen pro teams that recognized this overlooked pipeline. Eight starters on the 1969 Super Bowl champion Kansas City Chiefs were HBCU products. Scout Bill Nunn fashioned a legend for himself by identifying the HBCU stars - including Blount, John Stallworth (Alabama A&M), and Donnie Shell (South Carolina State) - who powered the Pittsburgh Steelers' 1970s dynasty.

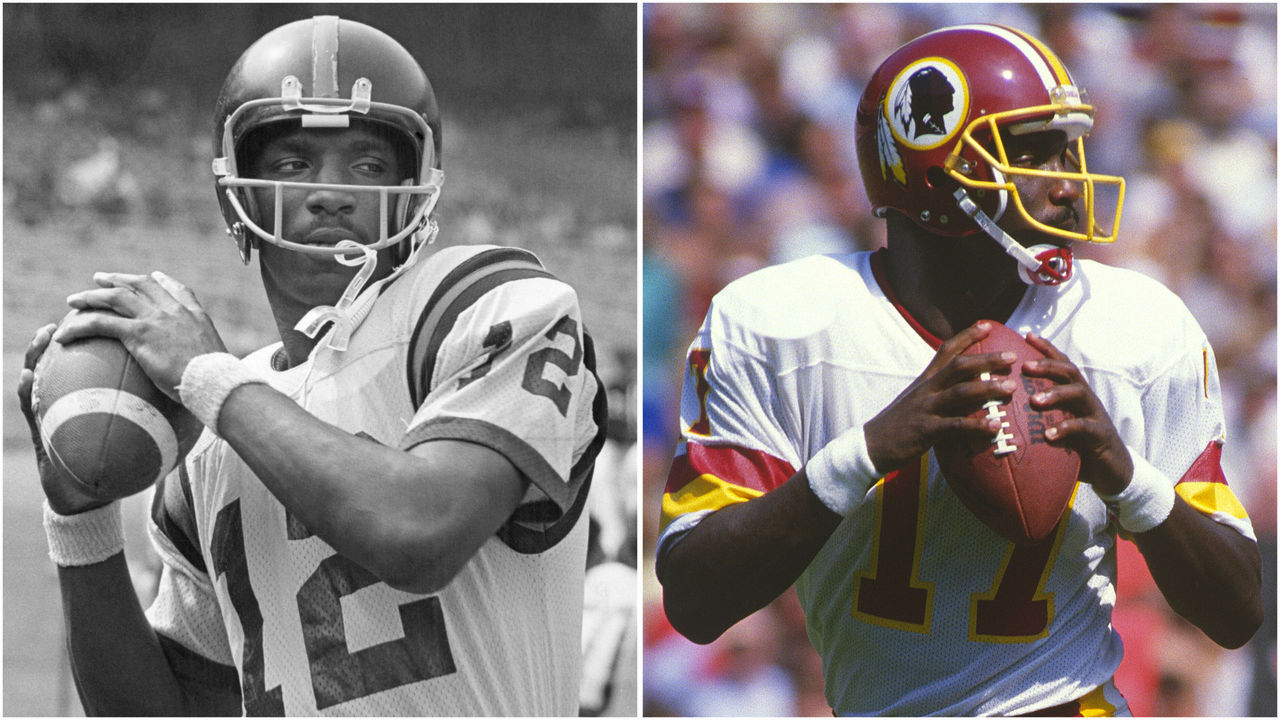

"Before integration, the place to be was HBCUs if you wanted to play football," said Doug Williams, the first Black quarterback to win the Super Bowl. He reached the NFL in 1978 via Grambling, whose iconic head coach Eddie Robinson won 408 games, 17 SWAC titles, and nine Black national championships over 55 seasons at the helm.

"(Robinson) was concerned about you not as a football player, but as a young Black man. You got that at the HBCUs," Williams said. "If it did anything, it has helped me survive America better. I went there and understood the uphill battle as a Black man that you're going to have to deal with."

One basketball and one football game changed the course of HBCU sports history. In 1966, Texas Western's all-Black starting lineup topped Kentucky to win the college hoops national title. Four years later, Black USC players, led by future NFL fullback Sam "Bam" Cunningham, combined to score four touchdowns in a famous 42-21 victory at mighty Alabama.

Neither winning squad was from an HBCU, but they'd both been quicker to integrate than Adolph Rupp's Wildcats and Bear Bryant's Crimson Tide. Those Southern institutions finally were spurred to follow suit, erasing the most significant edge that HBCUs had over richer and better-known schools.

Budding stars still headed to HBCUs into the '80s and '90s: Charles Oakley, Ben Wallace, Michael Strahan, Shannon Sharpe. But a critical mass began to attend predominantly white institutions (PWIs), and the resource gap between these schools kept widening. When USA Today ranked 227 Division I athletic programs by their 2018-19 revenue, the top-grossing HBCU, Prairie View A&M, placed 147th; seven HBCUs were in the bottom 10. Beyond sports, the average PWI's endowment is eight times larger than that of the average HBCU, per the Thurgood Marshall College Fund.

There's an abundance of statistics to illustrate how HBCUs have slipped in competition. Since March Madness expanded to 64 teams in 1985, four HBCUs have advanced past the first round; only once (Norfolk State in 2012) has that happened in the past 20 years. Between 2015 and 2019, a mere 1.4% of NFL draft picks (18 in total) hailed from HBCUs, The Undefeated noted last year. One lone Jackson State player has been drafted since 2000, a far cry from Payton and Tigers teammate Robert Brazile going fourth and sixth overall in 1975.

By the time Sanders joined Jackson State and Maker signed to play for Blakeney at Howard, HBCU coaches had long stopped pursuing blue-chip high schoolers, conceding the chase to programs with swank facilities and regular screen time on national TV. Case in point: Jackson native Mo Williams. The retired NBA vet's parents and siblings have HBCU degrees, but he never considered going that route before he committed to Alabama in 2001, partly because schools of lesser stature figured they'd only waste time trying to land him.

"That's part of why I love the energy that's being dedicated to this today. At that end of the day, it takes players like me when I was in high school to do things like that - to make that jump (to HBCUs)," Williams said in an interview last fall, ahead of his first season as head coach at Alabama State.

"I applaud guys now who are even just listening. I feel the landscape will change."

As Carmelo Anthony opined on Instagram Live last June, weighing in on Mikey Williams' HBCU interest, "All it takes is one person to change history." More than one player is already trying to lead the charge. Noah Bodden, the top high-school QB in New York, turned down close to a dozen Power 5 offers last fall to sign to play at Grambling State next season. De'Jahn Warren, the country's No. 1 JUCO cornerback, decommitted from Georgia to headline Sanders' first recruiting class at Jackson State, joining a raft of three- and four-star prospects.

In football and basketball, the best-case scenario for HBCU resurgence begins with star recruits coming aboard and would culminate in a permanent power shift. As their arrivals on campus elevate a team's profile and fortunes, the idea is that this would beget more TV games, marketing dollars, and attention for the school, and that this cycle would self-perpetuate.

"That's a slow process. One player, two players, isn't going to change that. What one player or two players will do is shift the conversation for the next generation of players," said Jasmine Harris, an Ursinus College associate professor of sociology whose research has delved into the Black student-athlete experience.

"You get a couple more from that cohort and that changes the discussion for the cohort down the line. Maybe in 10 or 15 years, we have a couple of HBCUs which are thought of more as powerhouses."

There's an established argument for why students, elite athletes among them, should consider HBCUs. These schools "play an important role in the creation and propagation of a Black professional class," Jemele Hill wrote at The Atlantic in a seminal 2019 essay on the subject. Hill noted that HBCUs make up just 3% of four-year American colleges but have educated 80% of the country's Black judges, 50% of Black doctors and lawyers, and 40% of Black engineers and congresspeople.

Personal experience shapes these arguments, too. Covington, the Portland Trail Blazers forward, reminisced recently about the energy with which two of his Tennessee State professors - James Bass and the late Richard Miller - told stories of how they marched and sat in for civil rights in the 1960s. ("I got to learn from people who were part of our revolution," Covington said.) Davis, the Little League World Series hero, visited Hampton's Homecoming as a high school senior and felt like she'd stepped into a family reunion: "Everyone was saying hello to me, making sure that I felt welcome."

Before Gurley helped found HBCU Jump, she swam at North Carolina A&T, a Black student-athlete in a largely white sport who felt understood, cared for, and insulated from racism on her campus. At HBCUs, most students, coaches, faculty members, and administrators can relate to each other by virtue of their shared experience. To be there is to live in and celebrate Black culture daily. At schools like Howard, Blakeney said, "You have people who look like you, people who think like you, people who have very similar backgrounds, all rooting for one another."

"There's something magical about being in a setting with a bunch of young, vibrant Black people who have nothing but hope inside of their heart and a will to do what's going to make their life better," Gurley said. "I can't think of another place in the world where you can have that concentrated energy."

Is that immersiveness enough to counter the bright lights of the Power 5? Until HBCUs secure greater, consistent TV exposure, Harris said the average recruit with big career goals might balk at their overtures, fearing his name and capabilities won't resonate with pro decision-makers. (For what it's worth, none of the boys or girls named 2021 McDonald's All-Americans this week have committed to an HBCU.) To Kevin Broadus, the men's basketball coach at Morgan State in Baltimore, the onus is on HBCU coaches to convince players they can prepare them for the next level: "You've got to sell that you can get them to where they want to go."

Of course, Power 5 prestige isn't required to pique the interest of scouts. Covington wasn't drafted out of Tennessee State but scrapped to stick in the NBA for eight seasons and counting. There's no denying that PWIs are better funded and resourced, Broadus said, but as a former assistant coach at Georgetown, he's fond of echoing a sentiment he heard from John Thompson III: People, not buildings, win games and championships.

"At the end of the day, going to an HBCU, you're not short-changing yourself. You're doing the same thing. You're reading from the same textbooks. You're playing on a 94-foot basketball court. You're shooting a round, orange ball," said Broadus, who captained a nearby HBCU, Bowie State, in the 1980s before he moved into coaching.

"It's just a different look once you get there. I always tell guys, people around me: Get in where you fit in. If it fits you for the future - for the near future and the long-term - you should try it. Go to an HBCU. Just remember you're not going to school for just the four-year turnaround. This is going to last you for 40 years, wherever you go."

COVID-19 shutdowns and Maker's groin injury weren't the only blows to Howard's basketball fortunes this season. Senior transfer Nojel Eastern, who used to start at Purdue, never took the court and opted out in January to focus on training for the NBA draft. Three-star forward Kuluel Mading, who committed to Howard in November, reversed course in January to weigh all of his options. The hope to improve a Bison squad that went 4-29 in 2019-20, Blakeney's first season as coach, fell short with just that single win.

That victory came on Dec. 18 against Hampton. During 20 bullish minutes in the second half, it felt to Blakeney like a turning point. Missing Maker and playing their first game in two weeks, the Bison's early deficit peaked at 17 points. Then something clicked. Howard shot 60% from the floor after the break and won by five, gains from practice manifesting just in time for the rest of the schedule to be nixed.

Lowly milestones loom in 2022; it'll have been 20 years since Howard finished a season above .500 and 30 since the Bison won the MEAC and appeared in March Madness. Nonetheless, Blakeney's ambition for the program is grandiose: Join the ranks of the game's consistently strong mid-majors.

He finds inspiration around the country, from No. 1-ranked Gonzaga to 1970s-era Georgetown, which scuffled for decades before the late John Thompson was afforded years to build a contender, culminating in three Final Fours and a national championship in the 1980s. As an assistant at Harvard from 2007-11, Blakeney saw Tommy Amaker turn a school that was indifferent to the sport into an Ivy League hoops power.

"It gave me the vision and the insight to how it can be done at Howard," Blakeney said. "Using a great brand that has incredible academics in one of the best cities in the country, (that's) the blueprint of how to be successful."

Season ended early but story is far from written. #MakerMob pic.twitter.com/Mlrpu4fkdo

— MK (@MakurMaker) February 11, 2021

With that in mind, Blakeney said, it wouldn't make sense for Howard to cold-call dozens of five-star prospects annually. If another blue-chipper is to follow Maker there, he said, "it has to be the right person," a player who appreciates the school's history and academic standing. Maker wasn't available to be interviewed, but Blakeney offered his perspective on why Maker was a fit: his spirit, his worldliness, his desire to study and play somewhere that he'd be nurtured and challenged to grow.

Asked last week if Maker plans to return to Howard for his sophomore season, Blakeney stuck to the facts at hand: He's still enrolled in school, taking classes, and training on the court. Maker had thought in the past about jumping to the NBA, Blakeney said. The coach figured he'd consider it again.

If Maker returns and benefits from better health, he should get to face Notre Dame at home next MLK Day; Brey and the Irish have already pledged to make the trip to D.C. For now, pondering Maker's future, Blakeney said he hopes he'll become a Howard graduate, be that in three years' time or later in life. As long as he's with the Bison, one program-wide goal will be to help maximize his draft stock.

"But in doing that, we also want to win games and we want to win championships," Blakeney said. "It would be great to have his name beside a banner or a championship, a title, where we can say: He's not only a good player. He's also a winner. I think that goes a long way."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.