Who was Woody Strode, Hollywood star who broke the NFL color barrier?

In the twilight of his film career, Woody Strode reflected on the opportunities he was denied and others he seized. The pioneering Black character actor relocated from the United States to Europe for a while to pursue bigger and more interesting roles.

“Race is not a factor in the world market," Strode said. "I once played a part written for an Irish prize fighter. I've done everything but play an Anglo-Saxon. I'd do that if I could. I'd play a Viking with blue contact lenses and a blond wig."

In movies and life, Strode's range was remarkable. He wrestled professionally before rapt audiences. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, unloading bombs in the Pacific.

As an athlete, he helped integrate the NFL.

Born in Los Angeles in 1914, Woodrow Wilson Woolwine Strode died at age 80 on New Year's Eve 1994. He was interred with military honors at Riverside National Cemetery, east of his hometown. Strode's Associated Press obituary praised his work in Westerns and period dramas, but didn't mention the trail he blazed on the gridiron.

He signed with the Los Angeles Rams in 1946 alongside Kenny Washington, an electrifying rusher and college teammate at UCLA. The Cleveland Browns brought aboard Marion Motley and Bill Willis that same year. This quartet struck a blow for racial inclusiveness in pro football as Black Americans sought it nationwide.

Keyshawn Johnson wrote a book about them. The retired NFL wideout, in tandem with his co-author Bob Glauber, persuaded the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2022 to recognize the so-called Forgotten Four as pathfinders. This past August in Canton, Ohio, family members accepted the Ralph Hay Pioneer Award on the players' behalf at the enshrinement gala that precedes the NFL season.

"It's heart and guts. Perseverance. I couldn't do it. But it says a lot about them to be able to do what I would call something for the greater good," Johnson, reflecting on the Forgotten Four's feat, told CBS News this year.

"You can't tell the story of the National Football League without telling the story of these four men," he added.

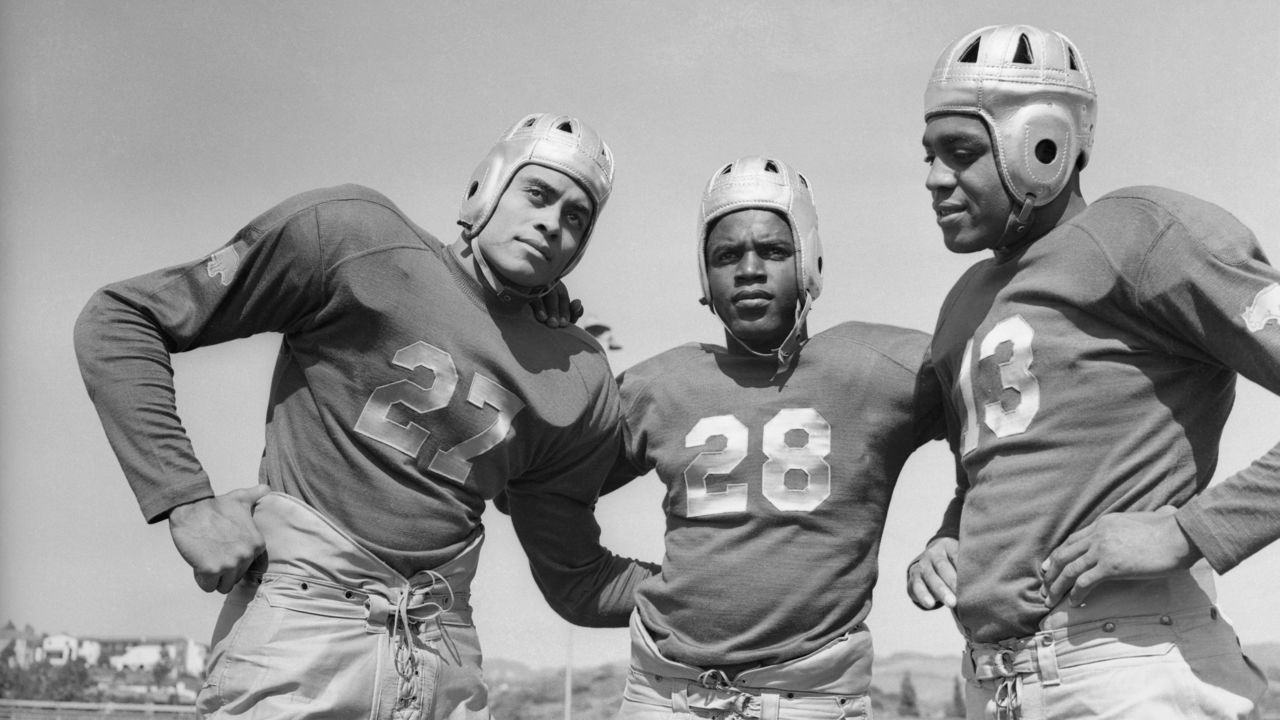

Once dubbed "the Jackie Robinson of cinema" by Jet Magazine, Strode shared a backfield with Robinson and Washington in 1939. Robinson played college football at UCLA before he shifted to baseball full time and made history. Robinson debuted in the majors with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, breaking the color barrier in that sport several months after his Bruins teammates reached the NFL.

Strode and Washington, an All-American in 1939, linked up the following year with the Hollywood Bears of the minor Pacific Coast Professional Football League. Racial discrimination slowed their progress in the game. A handful of Black players suited up in the NFL in the league's earliest seasons, but franchise owners at the behest of George Preston Marshall, the segregationist founder of the Washington team, conspired to exclude them from 1934 to 1946.

"The ban mirrored the status of Black Americans at the time: separate, unequal, and living in a de facto apartheid state via Jim Crow in the South and a patchwork of exclusionary laws and customs everywhere else," Patrick Hruby has written at The Guardian.

The ban collapsed when the Rams, founded in Cleveland, uprooted to Los Angeles in 1946. Local sportswriter Halley Harding, a retired Negro Leagues shortstop, led a civic campaign that pressured the Rams to integrate as a condition of playing in the publicly funded L.A. Coliseum.

The club signed Washington and Strode that spring. The expansion Browns, trying to build a winner in the upstart All-America Football Conference, added Motley and Willis and went on to claim four straight league championships before the AAFC and NFL merged.

"These four men created a foundation on which generations built," Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, once said. "Their actions on and off the field opened a door that allowed other people to follow."

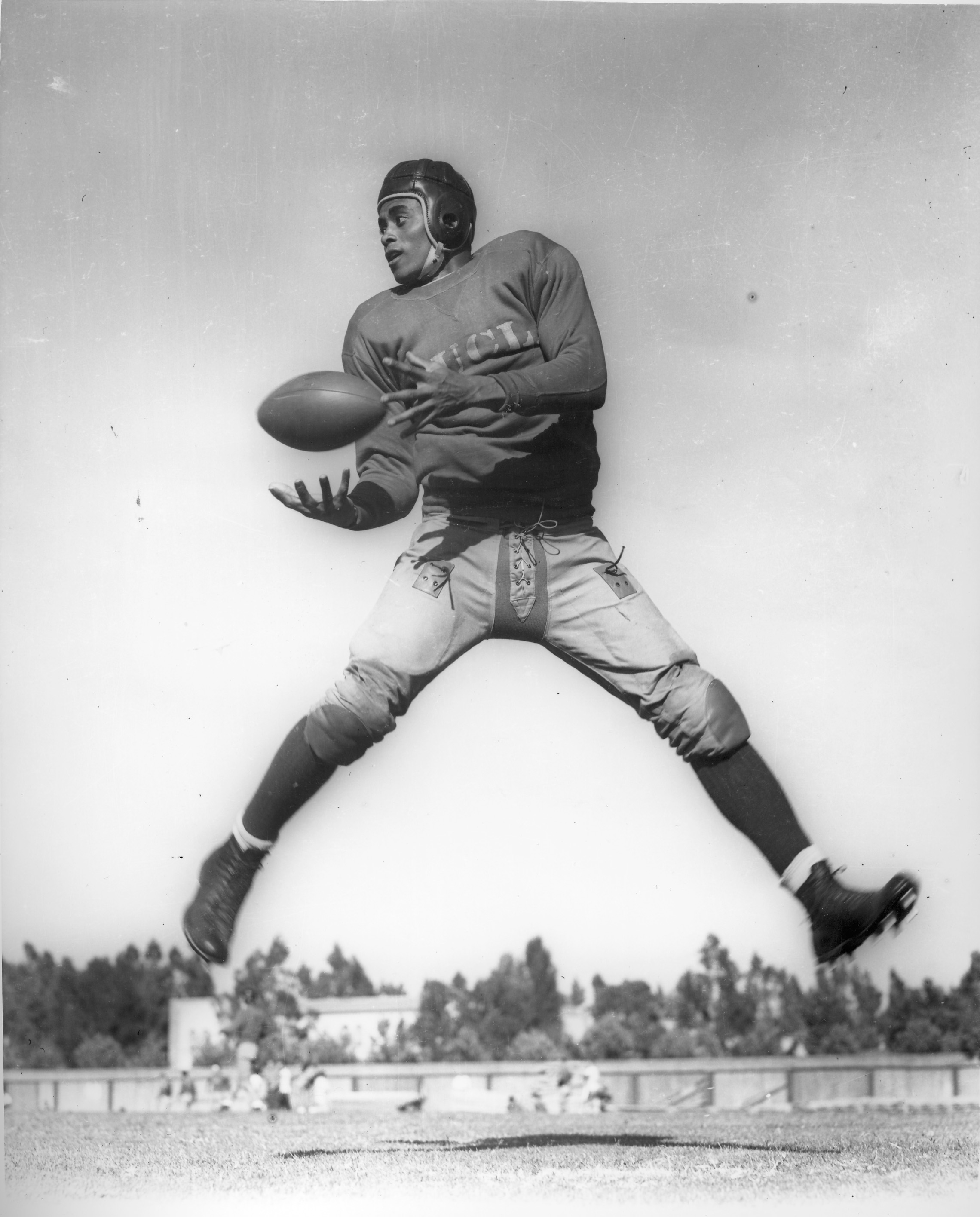

At 6-foot-4 and 210 pounds, Strode was an athletic marvel in his prime. He did 1,000 push-ups, sit-ups, and knee bends daily. He could beat Glenn Morris, the 1936 Olympic gold-medal decathlete, in all of his events except sprints. But by 1946, Strode was 32 and the oldest member of the Rams as a rookie.

An offensive end, Strode caught four passes for 37 yards and bowed out of the NFL after 10 games. Four years Strode's junior, Washington scampered for a 92-yard touchdown in 1947 and spent three seasons with the Rams before retiring. Meanwhile, Motley ran rampant as a Browns halfback and Willis was an All-Pro defensive tackle, which landed them Hall of Fame nods as players.

Strode encountered racism in the NFL. Rams owner Dan Reeves didn't like that Strode's marriage was interracial: his first wife, Luana, was descended from a Hawaiian queen. Opponents from the Deep South resented having to share the field with Black men, the producer of a documentary film about the Forgotten Four, Ross Greenburg, told the UCLA newsroom in 2014.

"On every play, if you're a (skill player) like Motley, Washington, or Strode, you can get pounded on the ground and beaten up," Greenburg said. "They suffered on the field. We heard stories about Kenny Washington where he was just battered throughout the entire football game."

Strode moved north and won the Grey Cup with the 1948 Calgary Stampeders, Canadian pro football's only undefeated team. He enabled the Stamps to score twice in the title game. Strode hauled in a pass while a teammate lay on the grass at the far sideline, which left that receiver wide open on the next snap. Doubling as a defender, Strode scooped an errant lateral at midfield and returned the fumble to the opposing red zone, teeing up a TD rush.

Calgary beat the Ottawa Rough Riders 12-7 in Toronto. Reveling in the win postgame, Strode rode a horse into the lobby of the team hotel.

Broken ribs and an ailing shoulder spurred Strode to retire in 1949. He wrestled intermittently, once defeating Gorgeous George. Producers approached him in 1950 to portray a Maasai warrior in a "Bomba, the Jungle Boy" adventure flick. The role set his Hollywood career in motion.

Strode racked up 91 acting credits in six different decades, according to IMDb. He graced the screen alongside Sean Connery, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, and John Wayne, plus Joe Namath when the Jets quarterback toyed with acting in the afterglow of his Super Bowl triumph. An able stuntman, Strode shot fire arrows and went so far as to bring his own 80-pound bows to set, he told The New York Times in 1971.

Often typecast as a physical specimen, commentators tended to dwell on Strode's athleticism and chiseled figure, ignoring his acting prowess, the film scholar Frank Manchel once wrote in the Journal of Black Studies. Strode brought the best out of his castmates while stealing scenes, sometimes before he spoke a line.

"Visually, he is a tower of strength and also a tower of endurance," film historian Donald Bogle said about Strode in a Turner Classic Movies segment a couple of years ago. "He is one of the most charismatic actors to work in American motion pictures. He simply does not have to say a word."

His big break came in 1960. Strode's performance in "Spartacus" as the gladiator Draba - who fells Douglas' titular character in a duel, but spares his life to defy the Roman elite - secured him a Golden Globe nomination for best supporting actor.

"I would have lost that role if I hadn't been in shape, and if I hadn't had a lot of experience as a wrestler," Strode told the Pittsburgh Courier after the film's release, according to Slam Wrestling. "It took skill to do that fight scene without actually hurting myself or hurting Douglas."

That same year, Strode played the eponymous soldier in "Sergeant Rutledge" - director John Ford's Technicolor Western - who is falsely accused of murder and rape. It was "one of the first mainstream Hollywood films to address racism frankly," the Hollywood Reporter's Seth Abramovitch wrote last year. Valuing his toughness, Ford cast Strode as Rutledge over future Oscar winners Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte.

"I've never gotten over 'Sergeant Rutledge,'" Strode told The New York Times years later. "It had dignity. John Ford put classic words in my mouth."

"Sergeant Rutledge" boosted Strode's profile but didn't catapult him to superstardom, the Times wrote in 1971, surmising "he and the film, with its sympathies strongly on the side of the Black man, were ahead of their time." He went on to depict myriad gunslingers at home and abroad. Never billed as a leading man in Hollywood, Strode moved to Rome in the late '60s to pick up prominent and lucrative roles in Spaghetti Westerns.

"I'll continue to work in Europe because I'm a star there," Strode said in 1982, per TCM. "I have the world market on my side even if I don't have the American market."

Strode last appeared on screen posthumously in 1995. Sam Raimi's Western "The Quick and The Dead," starring Sharon Stone, Gene Hackman, Russell Crowe, and Leonardo DiCaprio, is dedicated to him.

More tributes followed. Sheriff Woody, the beloved "Toy Story" protagonist, was said to be named after Strode. The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City last year enshrined him in the Hall of Great Western Performers.

Canton called this summer, feting Strode and the rest of the Forgotten Four at Johnson and Glauber's urging.

"To me, it's truly the beginning of more awareness of who they were, what they did, and why they were so important," Glauber told The New York Times ahead of the Canton ceremony in August.

"They are not household names like Jackie Robinson. I don't know if they ever will be. But they should be."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- Mendoza nearly chose Georgia: Call to Smart 'didn't go through'

- Georgia facing more reckless driving problems following recent arrests

- Northern Illinois coach Hammock resigns to take job with Seahawks

- Washington moves on from OC Dougherty after 1 season

- Rashada, Napier, others settle breach of contract suit over $14M NIL deal