Touted Intercontinental Cup revival evokes bloody memories

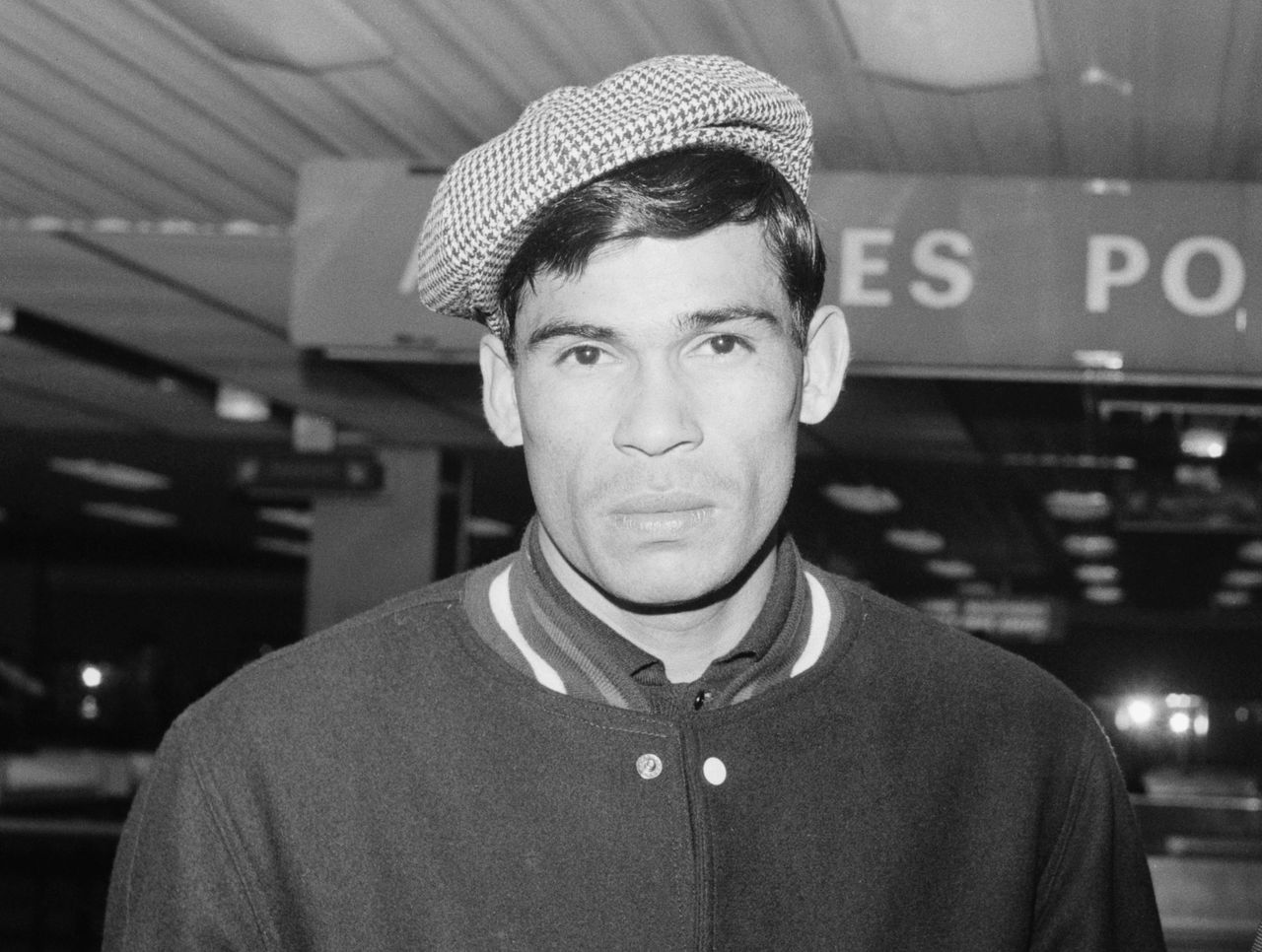

AC Milan forward Nestor Combin could've been forgiven for thinking things could not get worse after he suffered a broken nose and cheekbone during the 1969 Intercontinental Cup in a nightmarish return to his homeland Argentina.

That is, until Argentine authorities put him in handcuffs and rushed him off to jail in his bloodstained AC Milan strip.

(Photo courtesy: Action Images)

What happened at La Bombonera in Buenos Aires the infamous night that Milan clashed with Estudiantes was the culmination of several factors in a competition designed to allow the European and South American club champions a chance to go up against each another.

Thanks to the violence the event became associated with nine years after its inception, some European Cup winners boycotted or relinquished their place in the final against the Copa Libertadores champion, but the competition continued until 2004. There now appears to be a glimmer of hope that it could be revived, as CONMEBOL chief Alejandro Dominguez revealed that talks are underway over the possible reintroduction of the continental championship.

A glance back at what occurred 48 years ago, however, may cause tournament organisers to second-guess the International Cup's restoration to the football calendar.

AC Milan's triumph - its first of three titles in the tournament - instantly became an afterthought to the violence and divisive tactics employed by Estudiantes players.

The Argentine side's aggressive style shouldn't have come as a surprise considering the club's route to the title a year prior, when they kicked Manchester United around the park. The two-legged affair saw World Cup winner Nobby Stiles sent off at Old Trafford before United legend George Best was shown a straight red in the return leg after fighting defender Jose Hugo Medina minutes before Estudiantes was crowned champion.

(Courtesy: British Pathe)

But there was an increased sense of hostility in the air ahead of the return leg in Argentina, as Estudiantes faced the task of overturning the 3-0 result Milan manufactured at the San Siro two weeks prior.

Signs of unrest were evident before kickoff - Milan's pregame preparations were interrupted by a barrage of balls sent flying at the Rossoneri from Estudiantes players on the opposite side of the pitch. Later, the home support got in on the act and allegedly poured hot coffee on players as they emerged from the tunnel.

In hindsight, that was nothing compared to the outbreak of violence that was about to erupt on the pitch.

Pierino Prati was the first Milan player to feel the wrath of Estudiantes when he was left unconscious after receiving a blow to the head. Gianni Rivera avenged the act shortly after with a goal to increase the aggregate score to 4-0, but was later punched in the face by goalkeeper Alberto Poletti.

Poletti wasn't finished. He delivered the first of two major blows to Combin when he booted the Argentine-born forward in the face. Combin had been singled out by local media accusing him of traitorous acts by playing against a team from his home country. Later in the match, he received a bone-crunching elbow to the face, which the match official asked him to overcome before Combin fainted.

El milanista Nestor Combin víctima de la dureza de Estudiantes en 1969 pic.twitter.com/zJCjNhbhp6

— Alberto Cosín (@albertocosin) December 12, 2016

Combin's nightmare extended beyond the melee on the field, as he found himself in handcuffs shortly afterward on charges of draft dodging, which could have seen him sentenced to 30 days in prison. He spent the night in jail before convincing the police that he performed his military duties in France - where he lived and played for Lyon during the early part of his career.

Estudiantes won the match 2-1, but lost 4-2 on aggregate. The club's elimination was followed by several disciplinary ramifications for its players, including a lifetime ban for Poletti.

As several European Cup winners declined to participate in future tournaments, organisers attempted to quell the violence associated with the tournament by scrapping the two-legged format in favour of a one-match final in a neutral country.

Teams from both continents clashed in Japan from 1980 until the final edition of the competition in 2004. Once the event was discontinued, it was absorbed into the FIFA Club World Cup.

If the competition is rebooted in August 2018, as Dominguez suggests is possible, the world's biggest clubs will need to be assured of their players' safety in order to be convinced to take part and elevate the tournament's status.

Player safety is paramount in any football tournament in the modern era, but few events offer such a grisly example of what can go wrong within their own history.