The Retro: Bryan Lewis on Bob Pulford, death threats, and rules he'd change

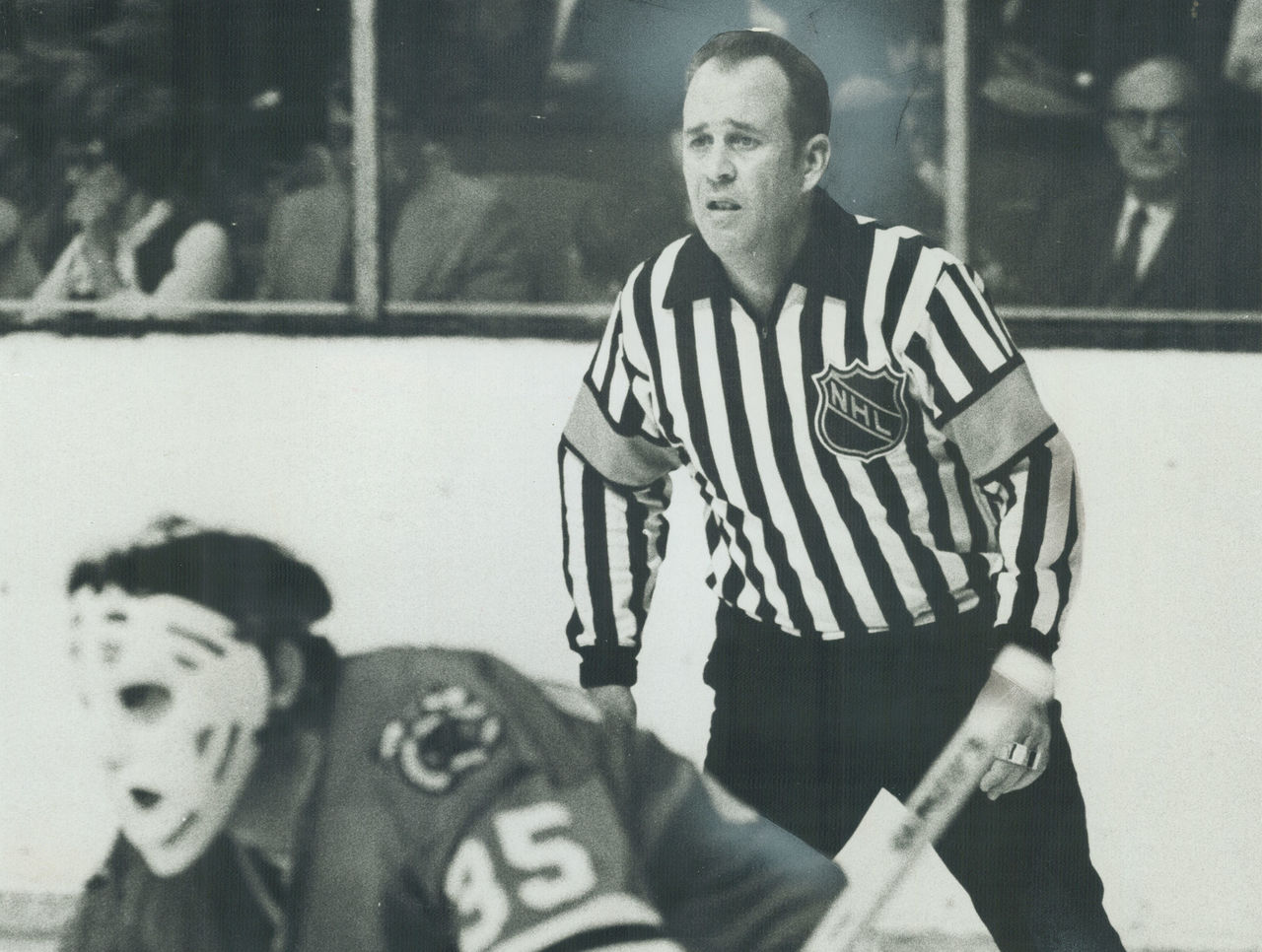

Over the course of the 2017-18 season, theScore will run a series of interviews with former players, coaches, and officials in which they recall some of the greatest moments of their careers. This edition focuses on Bryan Lewis, who was an NHL official from 1967-86 and served as the league's Director of Officiating from 1989-2000.

On what he remembers from his first NHL game:

I remember very vividly standing at center ice, shaking so badly that I thought, "If I keep moving here, I'm going to be at the blue line with the players lined up for the anthem." It was my first one, it was in Montreal ... I have a puck here that has the date here, I could tell you what date it happened. I can't remember who the visiting team was.

At the end of the day that's what you strive for. I had worked three years in the American League, the Central League, the Western Hockey League ... and to finally get an assignment that has an NHL logo attached to it, that's no different than a player trying to get to the NHL from the American League.

There was a little bit of comfort in the fact that I had officiated some of the players on the ice when they played in the American League. But once you drop the puck, that's long gone - they do what they can to win, and I put them in the penalty box when appropriate. I just remember being nervous as heck.

On the process of becoming an NHL referee:

Not only is the learning curve steep, but it's a long process. There are no shortcuts. Of course, today, with the two-referee system, it's a lot quicker to get into the NHL than it was. I had to serve an apprenticeship. Linesmen could come on board and go work in the National Hockey League in Year 1.

There was a time you went to the minors because it was an accepted part of your training. "Go learn your skills, guys. You're now dealing with pro players and not amateur players. Go down, learn your skills and come up." And in hindsight, it was a good process.

On what he learned over his first few years in the NHL:

My first training camp, my roommate was (former referee) John Ashley, who was a veteran at the time. That gave me the opportunity to say, "Hey, John, what would you do here, what would you do there?" I got some very candid comments as to what to do under various pressure situations.

I remember being on the ice with the Bobby Orrs and the Bobby Hulls and the Stan Mikitas. You had nothing but respect for them, as it was when I looked up to the veteran referees. But all of a sudden, you're on the ice thinking, "Oh my gosh, I used to watch him on Saturday night TV." And you're actually out there skating beside him, or even putting him in the penalty box.

Was it a thrill? Oh, it was - but you still had to stay focused. As big a thrill as it was to be on the ice with some top-talent athletes, I had a job to do. And you had to keep reminding yourself, "I cannot be a spectator out here. I am, in fact, a participant."

On dealing with big-name coaches:

You get on the ice, and you've got the Bob Pulfords and the Scotty Bowmans and the Glen Sathers ... it was a little bit more difficult to deal with those guys, because they've been around a long time. And you didn't come up through the process, so now you have to earn your stripes with each of those guys.

So you say, "Okay, I have to be strict, I have to be fair," with the idea that the rulebook is always going to be my ace in the hole, because I'm doing whatever it is I have to do in accordance with the rulebook. But in terms of skating over to the bench and actually talking to the Pulfords and the Bowmans ... you're intimidated sometimes to do it.

It could be my fifth game in the National Hockey League and I have Pulford on one bench and Sather on the other bench ... man, oh man, those were two tough people to deal with. So I did everything I could not to go there, because you never thought that you were going to win, and the last thing you want to do is turn around and say, "Okay, you've got a bench minor penalty." Pulford would be slamming the door as you skated away (laughs).

You learned to ignore some actions and some words from the likes of those people. Maybe they were right; they've been around a long time, and I was just a rookie, so maybe I didn't really know as much as I thought I did. So I wasn't going to get into a debate with those guys. But as long as I had the rulebook, I could say, "I know what the rule is."

On his most memorable colleagues:

I remember taking a bus from Springfield early in the morning on Peter Pan Bus Lines to get to Boston to have breakfast with Art Skov. Never once did I feel like Art Skov was not going to give me the right answer for fear that I was taking his job. And when I became the boss, I liked the way he handled stuff, so I used him as a supervisor because of the way he helped me.

Lloyd Gilmour is another name. Lloyd Gilmour would do stuff that rookies would never think about doing. I remember one time watching Lloyd work a game, and I asked him, "Hey, how come you don't go into the other zone?" And he said, "Sooner or later they're coming back." You couldn't function that way, but you appreciated his comments. He was very down to earth.

On his favorite player interactions:

On more than one occasion, you'd have a player come over and say, "The coach sent me here. He wants to know about this or that, should the faceoff be outside, don't give us a bench penalty, throw him out, I can't stand him, either." So you're covering your mouth so that people can't see you laughing.

You'd get that aspect brought to you a fair amount of times. "Have I been here long enough? Does it look like I've told you what the coach told me to say? Yeah?" And then away they'd go.

You'd have players come up to you and talk to you about the good-looking girl at the end (of the rink). They would say, "Can you take the faceoff to this side? There are better-looking people in this corner than that corner." Some were very, very humorous. Some were masters of it - and on the flip side, there were some that made me go, "Do you whine to your mom like this?"

On his least favorite interactions:

I had one unnamed player say to me one night going off the ice, "Someday, I'm gonna cut your f---ing eyes out." Or you'd have the booster club say, "Next time you come to such-and-such city, we're going to shoot you." So you sit there thinking, "Jeez, I hope the guy's a bad shot, I've got games in that city" (laughs).

Off the ice, only once in my 18-year career do I recall a player saying anything to me I would consider to be bad after a game. It was a Pittsburgh player who was brought up from the minors, and the game was in L.A. I recall this player saying something that was very, very bad. And I remember his teammates putting him in his position about not doing that kind of stuff.

On what he brought to the director role from his time as an official:

When I became the boss, I remember a guy coming to me that wasn't married. He said, "Bryan, even though I'm not married, that doesn't mean I don't want to go home." And I never forgot that.

When you're doing road trips, you realize the value of guys being home and maybe getting the odd weekend off or coming home to Toronto and doing a game Wednesday night so that you could stay home an extra couple of days before you had to work in New York on Saturday.

Because you lived it, those were the kind of things you were thinking about all the time for other people, and just trying to treat them in what you considered to be the proper manner.

On how he handled Stanley Cup games:

You have to realize the importance of it. That was always put in our minds. Where it really showed up: the importance of not having a marginal or poor-quality penalty. The idea was that marginal penalties do more to upset the flow of the game than they do to control it.

We did everything we could not to have a marginal/poor-quality penalty. Here's the worst-case scenario: It's 0-0, you have a poor quality penalty, the other team scores on the power play and wins the game 1-0. You can't get out from under that.

We were always charged with, "Oh, yeah, sure, you put your whistle in your pocket in the third period." No, the players are playing differently. And an unnamed general manger said to me one day, "Why don't you have them referee the first period like they do the third?" And my response was, "Have them play the first period like they do the third."

On what he would change in today's game:

To me, being shorthanded should be a penalty; you've done something very bad. I remember the days when you couldn't come out of the penalty box when a goal is scored. I'm not championing that cause. But it should never be to my advantage to be shorthanded and then to shoot the puck down the ice so that the other team has to get the puck and come all the way back.

Another one I would change: Let's say it's 3-3 with 30 seconds to go. We take a faceoff in your end, you have the best center in the league, and he shoots the puck down the ice. The other team has to skate down the ice, touch the puck, and then play is stopped. I would have the whistle stop the play immediately once the puck crosses the goal line in order to stop the puck.

The other one I would change: The goal line runs from the ice surface to the crossbar. Why can't the blue line go from the ice surface to the top of the boards? So that if a person is coming down the ice and he's stretching to stay onside, and his right skate is in the zone, and if his left skate is in the air ... what's the difference between that and keeping a foot in contact with the line?

If his foot is on that imaginary blue line to the top of the boards, I would say he's onside.

(Photos courtesy: Getty Images)

Other entries in this series: