The Retro (Part I): Kerry Fraser on breaking in, Beatle haircuts, and battling Gretzky

(Warning: Story contains coarse language)

Over the course of the 2017-18 season, theScore will run a series of interviews with former players, coaches, and officials in which they recall some of the greatest moments of their career. This two-part edition focuses on Kerry Fraser, who spent 30 years as an official and worked 13 Stanley Cup Finals.

On growing up a hockey fan:

Every Saturday, the whole family gathered at Grandma Fraser's house; she cooked a huge pot of spaghetti and meatballs. My dad and his brothers played guitar, and my grandfather played the violin. After dinner, we gathered in the living room, and the guys got the instruments out and played - everybody sat around and tapped their feet.

And then, at 8 o'clock, the guitars were set aside, the violin was set aside. It was Hockey Night in Canada with Foster Hewitt. We were just glued to the television to watch the Leafs play. That happened every Saturday night for as long as I can remember. I remember being in that house and watching the Leafs win the Stanley Cup in '67.

On switching career paths from hockey player to official:

I gotta tell you, I fell out of the sky. My ascent to the NHL was very unique.

I'm looking at a picture of my desk of the Haliburton referee school I attended after playing my final season of Junior B hockey as the captain of the Sarnia Bees. I was a good little player. There was a lot of players in that league that ended up moving on to bigger and better things.

I had a bunch of U.S. Division I hockey scholarship offers. I wasn't so inclined academically at that point to take advantage of what I had offered to me. A friend of my dad, who was coaching the Port Huron Flags in the IHL, he said, "Listen, you're a good little player, you're tough ... you could certainly play in our league, but that'll be the extent. Why don't you get into officiating?"

He handed me a brochure for a referee school. And 1972, as you'll recall, was the initial formation of the World Hockey Association. There were opportunities for players, and there also were for officials. Bill Friday had jumped from NHL officiating to the WHA for a million bucks. So I went to this referee school, paid $250, and I really applied myself. I was going to learn to be an official.

During that week, I knew I was getting some attention from the instructors. And on the Thursday night, I was scheduled to referee 10 minutes of an intermediate-quality men's league.

Frank Udvari, former NHL referee and Hall of Fame member, attended the camp. I get off the ice after my 10 minutes, and Mr. Udvari met me and said, "I really like what I saw. I would like to invite you to the NHL training camp for officials. But if I get you a spot, you gotta get a haircut." I had a Beatle cut at the time. I said, "That's an easy fix."

So I get up really early ... 2 a.m. on Sunday morning. And I'm standing at the front desk at the Hilton Hotel (in Toronto) at five minutes to 5. And I say, "I'm Kerry Fraser, I'm here to check in with the National Hockey League officials." And the guy looks at me and says, "Man, you're awful early. You guys aren't supposed to be here until 5 o'clock tonight." (laughs)

On breaking into pro hockey in the mid-1970s:

The veterans would check out the invitees, and see whether they were decent guys, whether they were people they wanted to associate with. And after three days, I was welcomed into the fraternity. Dave Newell came up to me and said, "Man, I wish I could skate like you."

I knew enough as a rookie that you just had to keep your mouth shut and your eyes open, and you'd learn a lot. And I did. We didn't have a lot of coaching or supervision back then. I learned so much by sitting around the veterans, listening to them, and having them accept me into their hierarchy.

My first exhibition game I did as a linesman, it was the Minnesota North Stars and the Detroit Red Wings. I really didn't know what I was doing; I had to learn on the job. The following year, they put me in the American Hockey League. I did about 60 games that year. It was a real learning experience.

On his funniest colleagues:

Lloyd Gilmour was a very funny guy.

We had 10 days of training camp, and the days were long. And each day in the afternoon, we'd sit in the chalet in Mississauga by the ski hill, and (head of officiating) Scotty Morrison would have us reading the rule book, going through it rule by rule by rule. Reading them. Talking about them.

We were talking about spearing - and back in 1972, there were two parts to the spearing penalty. At the referee's discretion, it could be a minor penalty, or a major penalty. So I looked over to Lloyd and asked him, "What's the difference between a two-minute spearing penalty and a five-minute penalty?"

Lloyd looked at me, deadpan, and said, "Kid, if you see the stick go in, that's two. If you see it come out the back, that's five."

On the challenges of working with different officials:

When I started, there was no question that the referee was the boss. It was a rite of passage. The referee was in control; he made the call on everything. It was almost like serfdom, to the point where the junior linesman would arrange the cab, while the referee made the decision on where we would have lunch. It was really a strange dynamic.

When I was on the ice, I was in control. There was a situation that I had with (John) D'Amico in the first year I worked the Stanley Cup Playoffs; it was in Round 1. I was in St. Louis, and it was a three-out-of-five, and I had Game 4 in the St. Louis-Chicago series. It was very intense; the rivalry was incredible. More fights in the stands than there were on the ice.

Al Secord was playing for the Black Hawks. St. Louis wins the game and forces a deciding Game 5 in the series, but we had a line brawl near the end of the game. Any time there was a secondary fight, you had to eject the player with a game misconduct. Al Secord got into a secondary fight, and had accumulated a one-game suspension because of the misconduct.

As John D'Amico was escorting Secord off the ice, the fans were throwing shit and booing. And Secord gave the fans a gesture that was offensive to D'Amico, a man of very proud Italian heritage. He came to me and said, "You gotta give Secord another game misconduct. I said, "What did he do?" And John said, "He just gave the crowd an Italian salute." (laughs)

If I give him another game misconduct, he's suspended for the final game. D'Amico said, "I don't give a (blank). If you don't give him one, I will." I said, "OK, John, I just want you to realize, he's not playing two nights from now." So I get home, and the phone rings as soon as I walk in the door. And it's Scotty Morrison. And he says, "What the hell were you thinking?"

I explained the situation. And Scotty just said, "Oh my God." And then he called D'Amico. So that was my indoctrination into the Stanley Cup Playoffs.

On working his first Stanley Cup Final:

The first one was special; it was 1985, between the Flyers and the Oilers.

I was the young kid on the block, the young gun. I received a tremendous among of media respect, and was being touted as the new "good" referee. It created some jealousy, and there is certainly that among peers. While it was exciting for me to be in my first Stanley Cup Final, I had to deal with some of the on-ice jealousy that moved into nastiness among a couple of colleagues.

It's disappointing, but I ended up working through it. John McCauley was a terrific mentor for me; he put me in Game 7 of that '85 playoff run (Quebec vs. Montreal) where I really broke out. The season before, I had worked two rounds in the playoffs; the season before that, I did one round. So I went one round, two rounds, boom. Stanley Cup Final. It was quite an ascent.

On his most memorable run-in with The Great One:

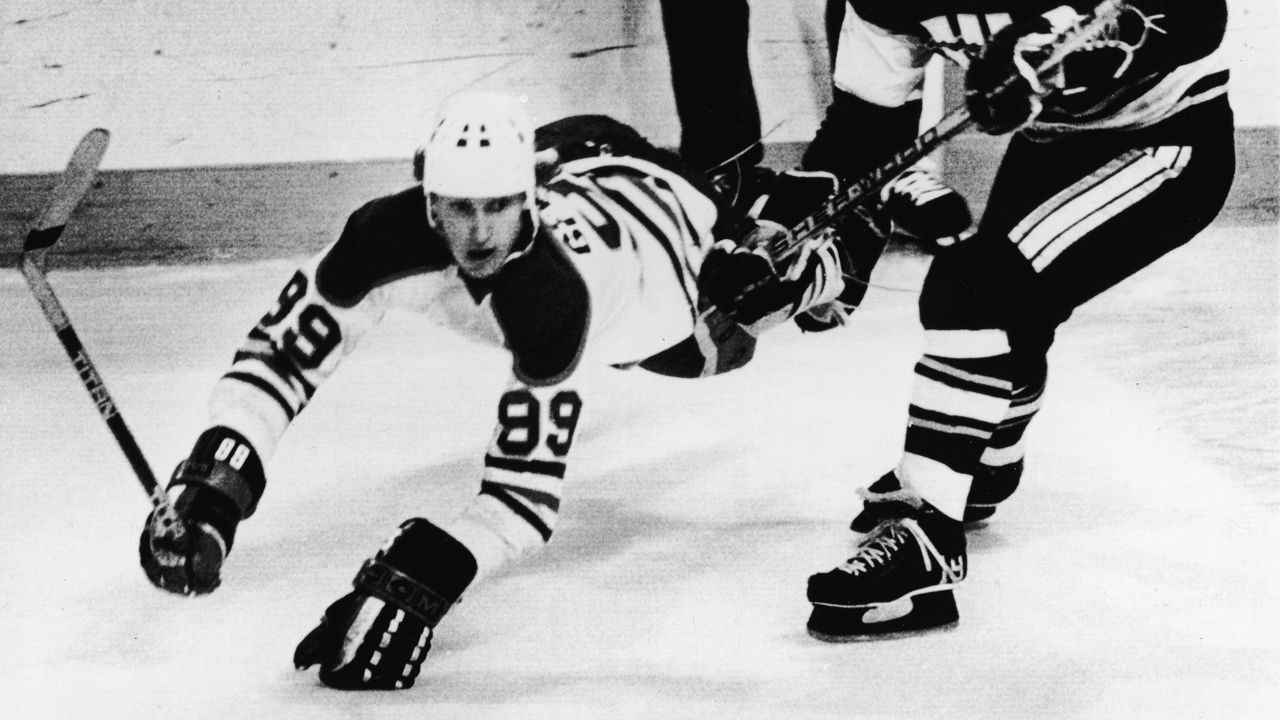

My success, I think, resulted from an awakening in a confrontation with Wayne Gretzky in 1980 in the Northlands Coliseum.

On his very first shift, Wayne took a dive. The guy just touched him, and Wayne went into the air - and he turned his head looking for me to see if my arm was up before he hit the ice. And my Type A personality was such that I thought, "I'm gonna show you." Every shift, the more he dove, the more stubborn I got. There wasn't one penalty he drew that night.

In saying, "I'm in control, I'm in charge," I was gonna make him pay. We didn't have a diving penalty at that time; the worst thing, for me, was to be fooled by a player. I didn't want to reward people that were trying to fool me or cheat.

The Philadelphia Flyers were up by a goal with just over a minute to play. And the crowd was on me all night; every time Wayne took a dive, they went crazy. The best opportunity (for Edmonton to tie the game) was a power play.

(Flyers netminder) Pelle Lindbergh caught the puck. I blew the whistle, killed the play. Wayne was standing behind the net, in his office. After I blew the whistle, he jumped in the air, threw his hands out one way, his feet out the other way, and boom - did a belly flop on the ice.

Bobby Clarke skated over to him with no teeth and said, "Get up, Gretzky, you (expletive) baby." I said, "Wayne, what are you doing? There was nobody within 15 feet of you." And Wayne said, "You wouldn't haven't called it anyway. You haven't called a (expletive) thing all night."

I said, "You're right. I'm gonna start right now. You've got two minutes for unsportsmanlike conduct." And he said, "Thanks. It's about effing time you called something." He stormed off the ice. And the Flyers won the game.

On how he dealt with the aftermath:

I went back to the hotel room after eating and having a few drinks with the guys, and I replayed the game. Was there something I could have done better? And it hit me like a board between the eyes.

I said to myself, "Kerry, you got into a battle with a player. And not just any player, but the best player in the game. You compromised your integrity, you compromised the rules, and you compromised your employer. You've gotta be better than that. You've gotta be bigger than getting involved in a confrontation with a player." And it was an amazingly valuable lesson for me.

I had to be part of the solution; instead, I was part of the problem. I needed to bring the temperature down. I needed to communicate better with players. So really, Wayne Gretzky taught me a valuable lesson that night. I had to be better. And from that moment, I did my best to be the best I could be.

(Photos courtesy: Getty Images)

Other entries in this series:

HEADLINES

- Wild trounce Oilers as Hughes sets franchise record, Jarry yanked

- Embiid's 40 points lead 76ers past Pelicans after George's suspension

- ESPN closes deal for NFL Network, rights for RedZone

- Report: Kings land Hunter from Cavs, send Saric to Bulls in 3-team trade

- Ullmark awarded 1st star in return: 'It was really hard holding it together'