Why Messi must win the World Cup for Argentina to love him

Lionel Messi is playing for more than the World Cup. He's playing for the love of his country, even though that love is unrequited. Because, in spite of all the accolades and trophies, Messi isn't celebrated like he should be. He's dismissed as a foreigner in many parts of Argentina. There's an absence of tributes back home, only a few murals in his old neighbourhood. The ones that are there, like his statue in Buenos Aires, have been vandalised.

It's unclear whether the negativity affects him. He lets nothing show but his brilliance on the pitch. Famously private, he seems to prefer it this way, doing as few interviews as possible and saying little of substance.

But it hurts him to lose, so much that he vowed to retire from the national team. He may not always sing the anthem or show outward pride for his country, but he has cried tears for Argentina. The burden of leading La Albiceleste felt no greater than after the 2016 Copa America final. In the immediate aftermath, he kept repeating the penalty he missed, another cross to bear for yet another defeat in an international final.

But it's almost forgotten how dysfunctional Argentina was. Its football association had been fighting court cases and the threat of administration, and couldn't even book the right flights. It was hardly a breeding ground for success.

And yet, no matter the circumstances, it has always felt like Messi's fault. Argentina's shortcomings have invariably been his own too. It doesn't matter that he's scored more goals than any other player in his country's history, that he single-handedly dragged Argentina to Russia, and that he turned down the chance to represent Spain as a teenager. He's done all he could for the national team. It isn't enough.

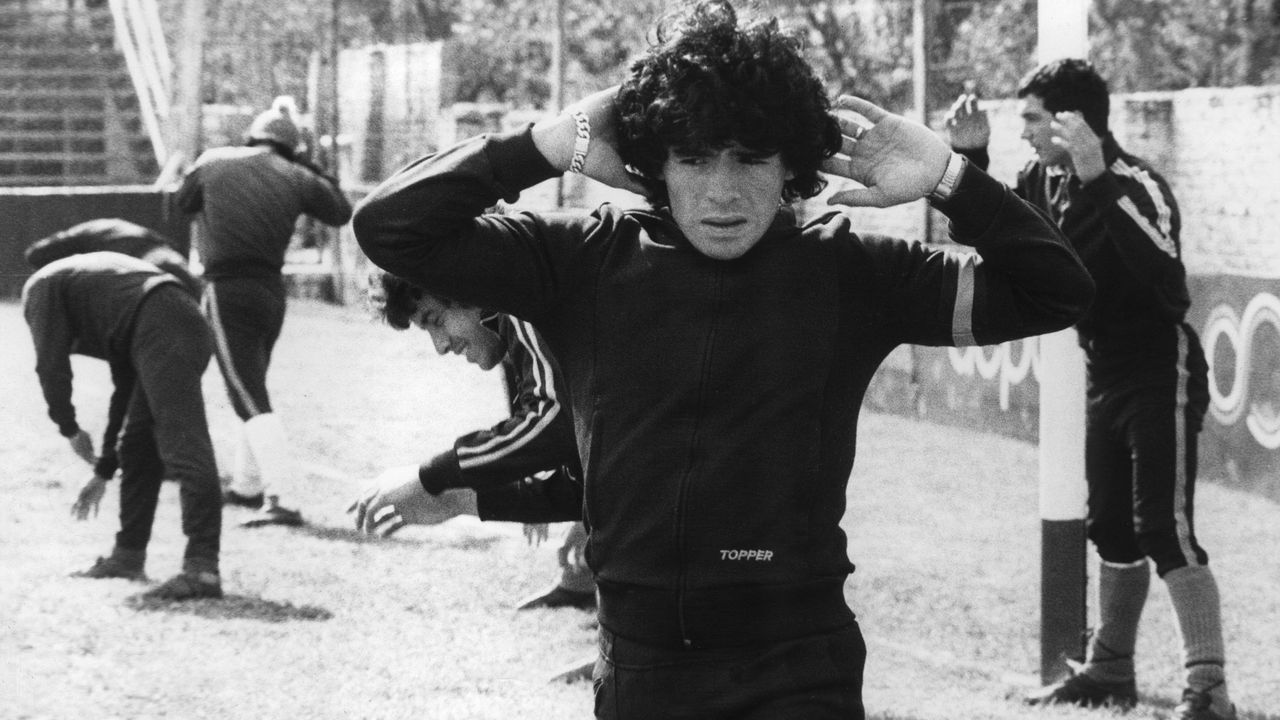

And it's because Messi isn't enough like Diego Maradona. Not in mind, body, or, more importantly, spirit. It's not so much his lack of accomplishments with the national team as it is Messi's lack of charisma, grinta, soul. The very essence of what it means to be Argentinian. The younger people may love him, but the entire population struggles to identify with the 30-year-old in the way they did Maradona.

"Messi is profoundly Argentine, but what Diego has is that we feel represented both by his virtues and his shadows," novelist Eduardo Sacheri told the New York Times in 2014.

Criticism was first related to his performances - he had only scored once in the 2006 and 2010 World Cups - but it soon became more personal.

The older generation attacks him because they don't know him like they know Maradona. Messi moved from his native Rosario at 13 years old to undergo growth hormone treatment in Barcelona, leaving behind a life now frozen in memory. Many of his former coaches, neighbours, and teachers recall Messi's bashfulness and pure innocence, but few have spoken to him since. Maybe a brief encounter with his parents, but nothing more. Even those who were once closest remain a significant distance away.

"The greatest gift for Messi during these years is that he never lost that Rosario accent," sports journalist Martin Mazur told the New York Times in 2014. "You can't imagine what it would have been for him if he hadn't had it. They probably would have killed him."

Even Messi's upbringing was held against him. He was born in a middle-class area of Rosario, and lived in a modest house with a small kitchen and two bedrooms. Maradona, on the other hand, was educated on the streets. He was kicked and battered while wearing shirts too big for him. His story was quintessentially Argentinian, his success everyone else's, his adversity a badge of honour.

Their personalities couldn't be more different. Maradona doesn't stop talking; Messi's interviews produce nothing controversial. The dichotomy only fuels the debate, which Argentinians love to have. It's been said the people of Argentina are singular in their pursuits, following one religion, one club, and one of Messi or Maradona. The fact Messi is so hidden from the public - a respectable life choice in this age of saturation - feels suspicious.

Maradona may have scored fewer goals and won fewer trophies, but the people love him because of who he is. They love him because he persevered through the conditions of his childhood and withstood horrendous tackles over the course of a painful career. Maradona's era was defined by man-marking, so his treatment was especially brutal. It has only added to the fallacy that Maradona played in a grittier era than Messi's.

"Messi is too correct and proper in a country that is attracted to and even demands the incorrect way," Guillem Balague wrote in his book about Messi. "People's fascination with him ends as soon as he crosses the touchline towards the dressing room; he is then no longer part of their world."

Of course, Maradona wouldn't have achieved god-like status without his magnificent performances in the 1986 World Cup. Contributing to 10 of Argentina's 14 goals in Mexico, Maradona helped his country win football's biggest prize for the second time. Victory was a release for the public, just four years removed from the Falklands War and the fall of military junta. It amplified Maradona's heroic return home.

Frustration, however, has set in. Argentina's drought is 32 years long. It has exacerbated the already gigantic burden on Messi's shoulders.

He must also contend with a team that's failed him on numerous occasions. It is widely believed Messi has a greater selection of teammates than Maradona ever did, but that's not necessarily true.

"During the World Cup, Maradona was brilliant, but so were other players," Argentina's coach in 1986, Carlos Bilardo, said in Jonathan Wilson's book, Angels with Dirty Faces. "It wasn't just Diego, even if he was fundamental. We knew how to surround him and make him feel comfortable. For example, the movement of (Jorge) Valdano in the final, starting almost at left-back and ending as a right-winger to score, that's when you say, 'These players know everything.'"

Messi's edition is lacking that cohesion. He may have able and talented teammates by his side, but they don't play for him like Barcelona does. He could only stand hopelessly as a streaking Gonzalo Higuain whiffed his shot wide in the 2014 World Cup final.

And it's still his fault.

So, he has to do a little bit of everything now, not because he's slowing down but because Argentina needs him. He's starting plays from deeper positions, teeing up goals, and scoring them himself. It's not uncommon to see Messi taking on multiple defenders at a time as his teammates watch.

But none of it will be enough unless Messi wins the World Cup. No one could misinterpret that.

(Photos courtesy: Getty Images)