In pictures: What it's like to eat, sleep, and train at La Masia

theScore's Gianluca Nesci spent five days in Catalonia leading up to Sunday's El Clasico between Barcelona and Real Madrid. You can find the complete collection of stories from the trip here.

BARCELONA - It trains over 700 young athletes - 79 of which live full-time on the campus - across five different sports, and is widely regarded as one of the leading talent incubators in world football.

Welcome to La Masia.

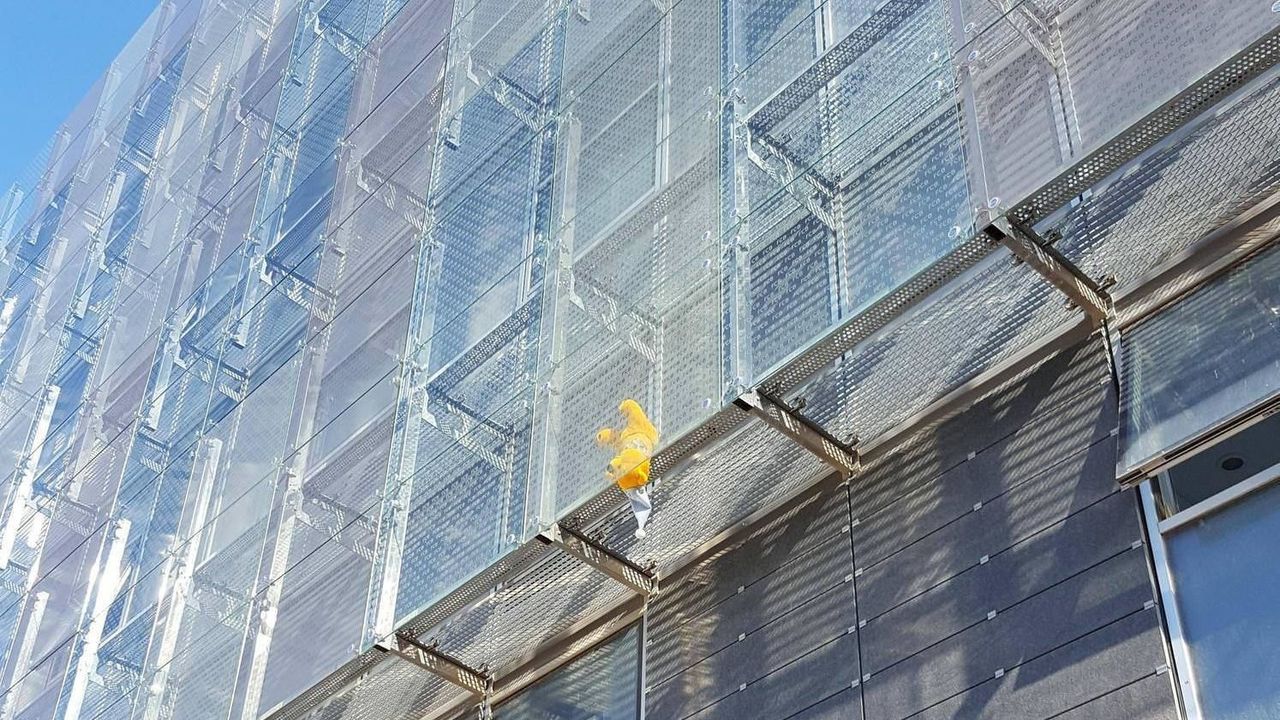

Barca's academy begins at age seven and children as young as 12 live in-house, so, naturally, the remnants of youth are on display. Somebody in the building is probably looking for a teddy bear:

Nestled at the heart of the club's Joan Gamper training complex, La Masia neighbors multiple training pitches. Both artificial:

And natural:

The football gets most of the attention, of course. But it's only part of the equation, according to La Masia's director of residence Juan Jose Luque, who leads the way on a tour of the 7-year-old facility.

Built in 2011, the current La Masia building replaced the club's original country house - Masia translates to "farmhouse" in Catalan - as the hub of youth development for the Blaugrana.

Featuring a large photo of the historic former residence, the reception area attempts to blend the old and new:

Upon closer inspection, the artwork is a who's who of Barcelona culture: the Camp Nou and Sagrada Familia in the background; the aforementioned farmhouse; young footballers with scouts looking on; Gaudi's Park Guell palm trees. The classic Barca colors, it's all there:

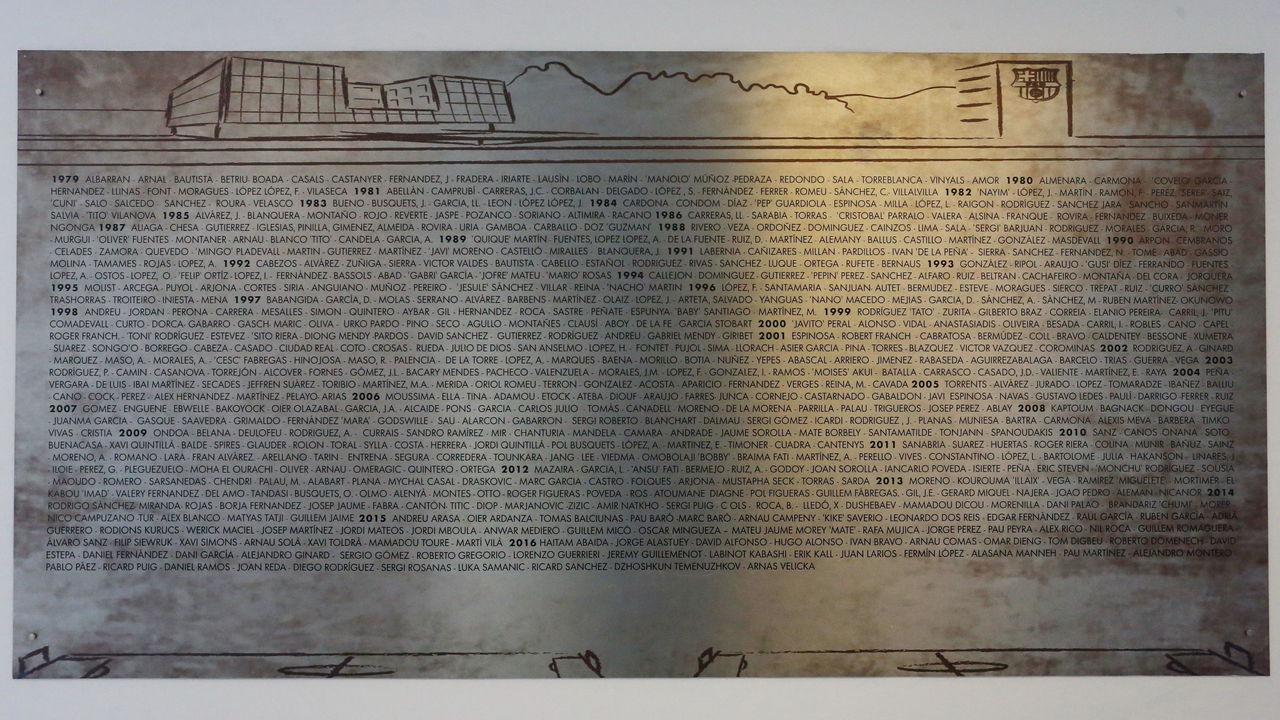

Featured prominently in the main hall that connects reception with the common area, a massive plaque is engraved with the name of every player to have lived at La Masia. All the usual suspects are visible: Puyol, Iniesta, Fabregas, Busquets. Those you may have forgotten came through Barcelona's academy - the likes of Icardi, Keita Balde, and Deulofeu - are there, too.

Leo Messi's name, easily the most famous to graduate from La Masia, is nowhere to be found, though. The Argentine - famously shy when he arrived in Catalonia from Rosario, Argentina - never lived in the iconic farmhouse, instead staying with his father, Jorge, in a flat near the Camp Nou.

The main floor is made up of a common area, multiple classrooms, and a dining room. The dorm rooms are found on the second and third floors of the building, with residents ranging from 12 to 18 years old, Luque explains.

"With 24 different nationalities, it can be difficult, but it's also an opportunity to manage children of different ages, cultures, languages, and religious beliefs," he says.

Coaches, tutors, psychologists, and nutritional experts - they're all there, Luque notes, outlining the holistic approach the club is taking to develop not only the player, but, more importantly, the person.

"We consider everything as a whole," he says.

A vintage foosball table sits in the middle of the common room. Ping pong is also an option, along with an air hockey table; the latter seems to be the least popular of the gaming choices (it's not plugged in).

The walls leading to the dining area are lined with photos featuring the likes of Andres Iniesta and Sergi Roberto spending time with the kids who idolize them.

The truth is, the vast majority of players at La Masia won't become professional footballers like Iniesta or Roberto, and of those that do achieve their goal, fewer will actually make the leap to Barcelona's first team.

That's where the schooling comes in.

Those aged 12-15 attend school outside of La Masia in the morning, Luque says, before returning for lunch and additional tutoring; every academy team under the club's umbrella has its own tutor. For the 15- to 18-year-olds who are considered semi-professional, their schedules mimic those of the pros: training in the morning followed by class in the afternoon.

Schedules are adjusted for those who spend time away from La Masia for tournaments, which becomes more and more common as the players get older.

Regardless of their area of expertise, the players should always be studying something when they're not out on the pitch, says Mario Ruiz, the academy's communications director.

He tells the story of one youngster, who came to his tutor one day with a message many a teacher - or parent, for that matter - has likely heard: "I'm not good at studying."

The response was simple: what would you like to do?

For many, their love of football shapes the answer to that question, and they begin the process of obtaining coaching certificates. This particular teenager, however, had a different path in mind.

"'I'd like to be a hairdresser,'" Ruiz recalls him saying.

A year's worth of schooling and a certificate later, and the unnamed academy player now cuts everyone's hair at La Masia.

"We focus a lot on this Plan B for life," Ruiz says. "If football doesn't work out for you, you need something else in life."