The tampering is not the issue: Can the NBA adapt to its player-movement boom?

We've just witnessed perhaps the most hectic transactional period in NBA history. With the dust settled, a lot of people are wondering what it all means, and what it might portend. Increasingly, those discussions boil down to one fundamental question: Who in the league holds the power?

The answer is fluid, but it's interesting that neither the players nor the teams like to posture as if they hold the advantage. Consider, as a minor example, the recent back-and-forth between Paul George and Thunder general manager Sam Presti over the nature of George's trade to the Clippers. George insisted the decision to deal him was mutual, but Presti disagreed. The league's identity crises tend to get hashed out in labor negotiations, so it makes sense for each side to play up the extent to which it's at the mercy of the other.

The next couple of years should be particularly fascinating as the NBA approaches another round of collective bargaining. As ESPN's Zach Lowe and Brian Windhorst reported, the league's 30 owners have already begun angling for change, airing a wide array of concerns that relate to free agency and the proliferation of player movement during their Board of Governors meeting earlier this month.

According to Lowe and Windhorst, the owners bristled at the rampant disregard for the league's transactional moratorium, noting how many deals appeared to be locked in place before the official start of free agency on June 30. That came after the Celtics reportedly complained about backroom discussions between rival teams and Al Horford - who ultimately signed with Philadelphia - during a period when only Boston was technically permitted to negotiate with him.

The league's owners have been guilty of misdiagnosing or overcorrecting for problems in the past, but ESPN's report suggests newfound adaptability. They were reportedly open to simply shortening or eliminating the moratorium, allowing teams to talk to impending free agents earlier (and out in the open) and making the whole process more transparent. That feels like a better alternative than the league "seizing servers and cellphones" to probe for any foul play - an idea that was reportedly floated by NBA general counsel Rick Buchanan as a potential enforcement mechanism.

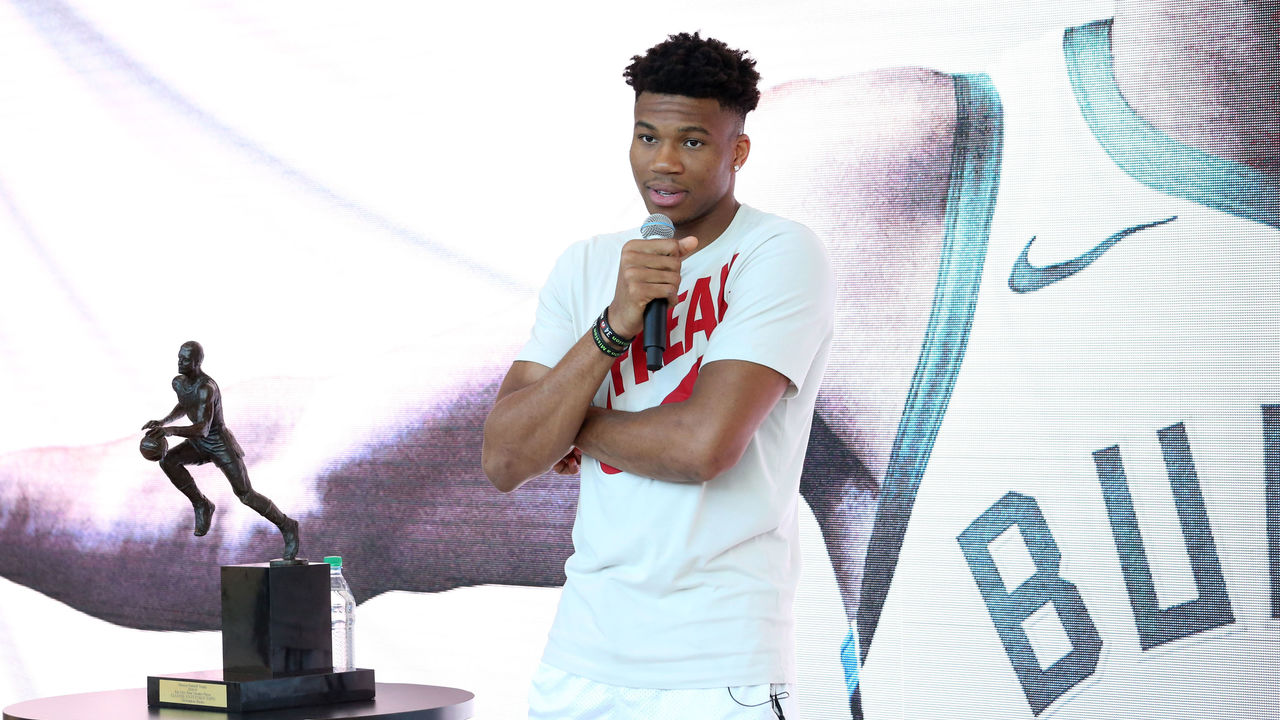

At the least, everyone should be able to agree that the current standard of discipline for petty tampering infractions - like fining the Lakers when Magic Johnson publicly uttered Giannis Antetokounmpo's name, even in a context that had nothing to do with free agency - is purely performative; it isn't doing anything for anybody.

It's also worth asking how much of an effect team-to-player recruitment even has at this point. Does anyone really believe that seeing Clippers president Lawrence Frank at a bunch of games this past season influenced Kawhi Leonard (who apparently didn't even know who Frank was), or that coach Doc Rivers comparing Leonard to Michael Jordan moved the needle when it came to his free agency? Did Magic's "Jimmy Kimmel" tampering episode do anything to sway Paul George, who didn't even take a meeting with the Lakers last summer? Would an illicit overture from Clippers GM Michael Winger - or even Jerry West - have done half as much to convince George to ask out of OKC as a recruitment pitch from Kawhi did? Was Anthony Davis lured to the Lakers by GM Rob Pelinka or LeBron James? (These are rhetorical questions.)

As Walter Sobchak might say, the tampering is not the issue here. At least, not the kind of tampering the league has made a show of cracking down on in recent years.

There are certainly measures that can be taken that would make it easier for teams to plan around their own free agents' decisions, but that doesn't necessarily mean the big picture would wind up looking much different. Because when it comes to the force that's increasingly driving player movement and shaping the NBA landscape - in other words, the players themselves - the league knows it's hard-pressed to impose viable deterrents.

From Lowe and Windhorst:

The league's constitution grants Silver the authority to fine and suspend any player who "induces, persuades, or attempts to entice" any player under contract with another team "to enter into negotiations for his services" - i.e., player-to-player tampering. The league has essentially punted on enforcing those rules. Some league and team officials find the prospect of such enforcement almost an invasion of privacy.

One legitimate concern is that the rise of player recruitment has widened the advantages big markets enjoy over small markets. When star players team up, they mostly aim to do so in the league's glamor cities. Even LeBron, for all his power-brokering influence, professed to having an almost impossible time trying to recruit his peers to Cleveland when he was a Cavalier.

Can the league do more to make playing in smaller markets palatable? Can it put more of those teams' games on national television - Nielsen ratings be damned - as part of a broader effort to close the visibility gap? How would that go over with broadcast partners? And how much would it really matter, anyway? Ultimately, a lot of these players are simply making lifestyle decisions, and the league can't do anything to alter the perceptions or realities of what it means to live and work in one place versus another. The margin for error is significantly slimmer for non-glamor-market teams, but there's never going to be a catch-all solution for that imbalance. Fighting against that reality has not proven successful for the league in recent years.

Regardless, that reality doesn't have to spell hopelessness for teams in less conventionally attractive markets. The Raptors just won a championship. The Spurs authored a two-decades-long dynasty. The Jazz built a sustainable contender once before, and may well be on the cusp of doing it again. LeBron did go back to Cleveland, after all, and even coaxed Kevin Love to join him there. Kemba Walker badly wanted to make it work in Charlotte. So did Russell Westbrook in Oklahoma City. By all accounts, Antetokounmpo would like to stay in Milwaukee long term.

History tells us that building a winning culture can keep wandering eyes fixed in one place, no matter where that place happens to be. You know what really hurts small-market clubs? When an aimless front office fumbles around for years without a coherent plan. Or when a billionaire owner of a billion-dollar franchise cheaps out when the team has a chance to build a sustainable winner. Refusing to pay the luxury tax to keep a James Harden - or even a Malcolm Brogdon - when you're already a championship contender is still more damaging to your team than a meddling opposing player or front office would be.

Between rookie-scale contracts, restricted free agency, and the exclusive ability to offer rookie extensions, teams get nearly a decade's worth of control over players they draft. And sure, if you factor in a few seasons of development on the front end for those players to reach their potential, and account for them potentially curtailing the back end by asking out early (sometimes with multiple years left on their second contracts), the window isn't as long as it appears. But there should still be plenty of time to craft a competitive team around an elite talent, and the rules still tilt toward player retention in the early stages of their careers.

Plus, it's not like team control disappears the moment a player asks to be moved or indicates that he won't re-sign. Teams are in no way obligated to honor trade requests. They do so because it benefits them, allowing them to recoup meaningful assets in return rather than eventually letting the player walk for nothing.

"I wouldn't say that we were going to appease the request simply because it was made," Presti said of trading George. "More than anything, it was because of the fact that we were able to get the return that we did, which then allowed us to accommodate what he was looking for, as well."

Plenty of people around the league would still prefer that contracts be played out in full. Warriors coach Steve Kerr was the most recent spokesperson to suggest players should be bound to their deals and to the teams that proffered them. But how do you square that with the fact that players are routinely traded against their will?

That's not to say trade demands are eminently good, or don't carry consequences. One ripple effect is the other players who get roped into those trades and have their lives uprooted as a result. In that regard, Damian Lillard's comments from earlier this year about why he hasn't felt compelled to pressure Portland's front office to make trades are instructive.

"I want to win a championship for this city, but I'm not willing to put somebody under the bus to do it," Lillard told The Athletic's Jason Quick. "That means more to me than saying 'I won a championship' but now this guy has been traded to a bad situation, and now his team don't like him as much and he might be out of the league in a year. I'm not going to have that. I'm not going to have that on me."

Lillard is one of a small handful of players around the NBA who even have the leverage to orchestrate significant moves, whether those moves involve themselves or their teammates. LeBron alienated half his teammates last season by not-so-subtly pressing the Lakers to trade them for Davis. When people talk about "player empowerment," what they really mean is "superstar empowerment." Most players in Lillard's position prioritize winning over empathy. The league is overwhelmingly made up of guys who don't have leverage, and those guys are increasingly being used as pawns in the superstars' games of multi-dimensional chess.

At the same time, star players make the league what it is, and their magnetism helps subsidize the league's middle class. Fans don't flock to arenas to watch mid-level guys play solid team defense and hit stationary threes. Having max salaries ensures that the best players don't get paid what they're truly worth; it's an artificial cap that benefits the NBA proletariat and balances the scales. For star players, pulling strings on the transactional market is one of the few ways they can tilt those scales back in their favor. The players who make up the ruling class are simply exercising the freedom their extraordinary abilities afford them. How do you prevent that from happening?

If the goal is to keep players in one place for longer, the league can try to bake certain stipulations into contracts that restrict movement. The union would surely push back on that, but perhaps as a concession, the league could loosen its restrictions on which players can negotiate no-trade clauses. (As it stands, no-trades can only be secured by players with at least four years of service for the team they're signing with, and at least eight years of NBA service time in total.) What about steeper penalties for guys who demand trades and hold their teams hostage? Davis probably didn't lose much sleep over the $50,000 fine he received for his public trade request, especially when he ultimately got exactly what he wanted. How much more punitive can the league reasonably get when it comes to said requests?

There's also a lot of grey area there. For instance, how would the league treat a situation like George informing the Pacers a year before his free agency that he wouldn't re-sign the following summer? That information forced the Pacers' hand, but it undeniably benefited them, too. They now have Victor Oladipo and Domantas Sabonis under team control - and therefore a far rosier future outlook - as a result.

There's always going to be something that rankles or frightens the owners, and as ever, they need to be wary of how they address their present concerns. During the 2011 lockout, they fretted over onerous long-term deals and put new rules in place to restrict the length of contracts - essentially as a way of protecting them from their own capriciousness. We're now seeing the ways in which that has backfired, with increased player movement being a direct upshot of shorter agreements. These days, one of the potential changes being discussed, according to Lowe and Windhorst, is a return to longer contracts.

Another idea reportedly under consideration: Provisions that give incumbent teams even more of a home-court advantage in terms of the years and money they can offer. Would that work any better this time than it did last time? The super-max provision was negotiated in the 2016 CBA, and if anything, the specter of that megadeal has created even more angst for the franchises capable of offering it. A fear of locking into it on the part of the team, or a refusal to sign it on the part of the player, has in some situations triggered trade talks even earlier than they might have otherwise taken place. And some teams that have signed players to super-max deals have already come to regret it.

Players, too, tend to lose their leverage after signing mammoth contracts, because of how difficult those deals are to trade. (Look at Chris Paul, stranded on a retooling Thunder team in the twilight of his career.) So, would they be any keener to sign a hypothetical super-duper-max, knowing how firmly it might root them in place?

There are no easy fixes to any of this. In some cases, no fix may be possible, or necessary. That doesn't mean the system can't be improved, or that worthwhile compromises can't be reached. But the league has to come to terms with certain ungovernable realities, and then hone in on things it can actually change while seriously considering the potential side effects of those changes. Otherwise, it will just perpetuate a cycle where it winds up chasing its own tail.

For now, a positive sign is that the owners seem comfortable with - or at least resigned to - the idea of sharing power with the players. We'll see how long that can hold.