Lou Gehrig: No. 4 on the scorecard and No. 2 in the public imagination

After "The Last Dance" reminded fans of the greatness of Scottie Pippen existing in the shadow of Michael Jordan, theScore's feature writers decided to examine some of the most compelling second bananas in other sports. The series began with NCAA football and continues with baseball.

Wally Pipp, felled by a headache, couldn't go.

Instead, New York Yankees manager Miller Huggins penciled a precocious 22-year-old named Lou Gehrig into the lineup, starting at first base and batting sixth, for a midweek matinee against the Washington Senators on June 2, 1925. Gehrig, making his first start in more than a month, capitalized on the rare opportunity, notching a pair of singles and a double in an 8-5 victory, his first multi-hit performance of the season.

For nearly 15 years onward, Gehrig didn't miss a game. Throughout that wondrous time in baseball, Gehrig - dubbed "The Iron Horse" as he toughed his way through 2,130 consecutive contests, a record that stood for nearly 60 years - helped steer the Yankees through the most prosperous stretch of their singularly prosperous existence, propelling them to six World Series titles with his mighty bat and famous durability.

By the time amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - the disease now known by his name - brought an abrupt and devastating end to his career, at age 36, Gehrig had cemented himself as one of baseball's all-time greats. Today, more than eight decades after he delivered his iconic "Luckiest Man" speech, you still need only one hand to count the hitters superior to Gehrig, a two-time American League MVP who boasts a higher lifetime on-base percentage (.447) than Barry Bonds and a higher lifetime slugging percentage (.632) than ... well, Barry Bonds.

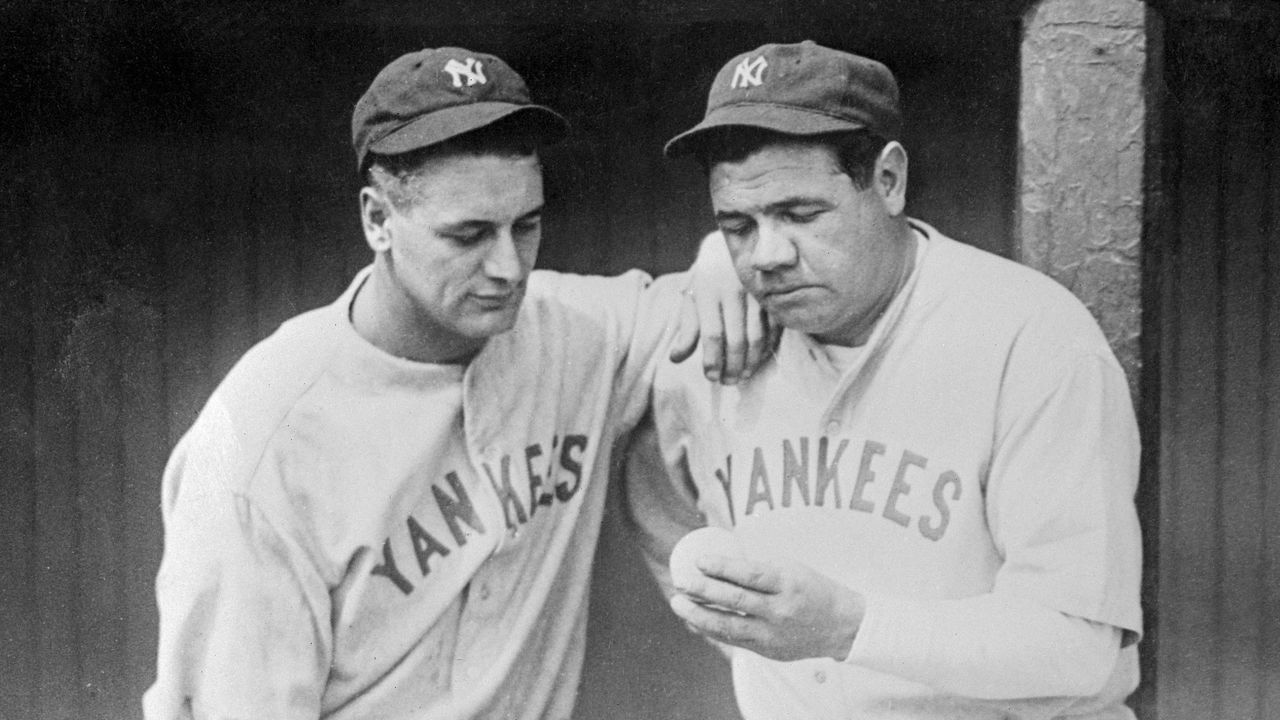

Yet, for the majority of his career, Gehrig wasn't even the best hitter on his own team. In fact, for all but the final five of his 17 years with the Yankees, Gehrig's greatness was overshadowed on a daily basis by the demigod hitting in front of him in the Yankees' lineup, whose revolutionary power and larger-than-life persona perpetually consigned Gehrig to the role of second banana.

"I'm the fellow who follows the Babe in the batting order," Gehrig said, as quoted by biographer Ray Robinson. "If I stood on my head, nobody would pay any attention."

When Gehrig debuted with the Yankees in the summer of 1923, days shy of his 20th birthday, Babe Ruth was already the game's most celebrated star and a bona fide celebrity who almost singlehandedly wrested the game out of the dead-ball era. That year, Gehrig played sparingly, receiving only 29 plate appearances. Ruth, meanwhile, hit 41 home runs, more than the entire Boston Red Sox roster, en route to his first and only MVP award (limited in number by a short-lived rule barring American League players from receiving the honor multiple times). As such, few noticed or particularly cared that the youngster slashed .423/.464/.769 in his limited action. And so began a pattern that would continue as long as the two played together: Gehrig's brilliance dwarfed by Ruth's even-more-jaw-dropping brilliance.

In 1925, his first season as a full-time player, Gehrig smacked 20 homers while managing an .896 OPS, establishing himself as one of the game's brightest young stars. Meanwhile, Ruth endured his worst season with the Yankees that summer, as his hedonistic lifestyle caused an intestinal abscess that curbed his productivity and limited him to 98 games, his lowest single-season total in his 15 years with New York. He still out-homered Gehrig and led the club's regulars in OPS.

Two years later, Gehrig broke out in earnest, exploding for 47 homers while accruing a preposterous 12.5 WAR as the cleanup hitter in the definitive Murderers' Row lineup, a unit widely considered the greatest offense of all time. Still, only by virtue of that misbegotten one-time-only rule did Gehrig earn that year's AL MVP award. Ruth deserved it more, after clobbering 60 homers - breaking his own record of 59 and establishing the single-season record that would stand until 1961 - while narrowly edging out Gehrig in OBP, slugging percentage, and WAR.

Gehrig kept up his pace for a decade after his superb 1927 campaign, in which the Yankees won 110 games and the World Series for his first championship. (Ruth, of course, outshined Gehrig in the Fall Classic, hitting .400/.471/.800 while accounting for both of the Yankees' home runs; Gehrig hit only .308/.438/.769 for the series.) With both hitters at the height of their powers, the Yankees were virtually unstoppable, the two titans - comprising the most fearsome one-two punch in baseball history - carrying the Yankees to three World Series titles from 1927 through 1934, Ruth's final year with the club.

Ruth vs. Gehrig, 1927-34

| Player | WAR/162 | OPS | wRC+ | AVG | HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruth | 10.6 | 1.151 | 193 | .338 | 352 |

| Gehrig | 9.7 | 1.118 | 185 | .352 | 311 |

Still, even after blossoming into a superstar in his own right - the second-best player in all of baseball, even - Gehrig remained firmly in Ruth's shadow, a dynamic reinforced by their diametrically opposed personalities: Ruth was the consummate showman, a flamboyant shot-caller; Gehrig was taciturn and shy. But even if Gehrig had been more extroverted, he wouldn't have been able to wrest people's attention or affection away from Ruth, who was a genuine cultural phenomenon.

"It's a pretty big shadow," Gehrig said. "... When the Babe was through swinging, whether he hit one or fanned, nobody paid any attention to the next hitter. They were all talking about what the Babe had done."

As it happens, Gehrig's opportunity to seize the spotlight was short-lived even after Ruth was released by the Yankees following the 1934 campaign. By 1936, Gehrig was once again contending for top-dog status in New York, this time with a 21-year-old named Joe DiMaggio, who gave Gehrig a decent run for his money in the 1936 AL MVP race as a rookie, and helped the Yankees secure their first of four straight World Series championships.

By the following year, DiMaggio had supplanted Gehrig as the Yankees' preeminent star, leading the majors in WAR, homers, and total bases in 1937. Gehrig, once again relegated to a proverbial supporting role, played only one more full season after that, benching himself for good early in the 1939 campaign amid worsening symptoms and retiring only a couple months later upon receiving his diagnosis. He ultimately finished his tragically abbreviated career in the manner he was most accustomed to: in someone else's shadow.

"Joe became the team’s biggest star almost from the moment he (joined) the Yanks," pitcher Lefty Gomez said. "And it just seemed a terrible shame for Lou. He didn’t seem to care, but maybe he did."

As a man without the "remotest vestige of ego, vanity or conceit," according to sportswriter Marshall Hunt, Gehrig was, in all likelihood, genuinely content to play second banana - the greatest in baseball history, to be sure. Gehrig made abundantly clear just how unflappable he was on July 4, 1939, when the outgoing icon was feted at Yankee Stadium by 62,000 fans; in response to his devastating and fatal diagnosis, Gehrig described himself as the luckiest man on the face of the earth.

It's hard to imagine such a man resenting having to take a backseat to Babe Ruth.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.

HEADLINES

- Redick: Luka 'vomiting all afternoon' ahead of Game 3 loss to Wolves

- Skenes strikes out 9, wins duel with Yamamoto in Pirates' victory over Dodgers

- Oilers score 10 seconds after Kings' failed challenge for Game 3 winner

- Wolves top Lakers in Game 3 to take series lead

- Running analysis of Round 1 of the Stanley Cup Playoffs