Marty Schottenheimer was one of the greats. Why didn't he reach a Super Bowl?

This story was first published on March 6 and is among theScore's best features of 2021.

On Jan. 5, 1998, the morning after the Kansas City Chiefs lost to the Denver Broncos at home in a divisional-round playoff game, Marty Schottenheimer met with a group of reporters to wrap up the season, as he always did. Schottenheimer dutifully answered every question, trying his best to explain the unexplainable, before he asked those present to turn off their recording devices and to close their notebooks.

"What," Schottenheimer asked the gathered press, as Mike Vaccaro of the New York Post recounted years later, "am I doing wrong?"

Schottenheimer died on Feb. 8 at the age of 77 after a lengthy battle with Alzheimer's. His death called to mind the striking duality of his NFL coaching career: consistent regular-season success across 21 seasons with four teams, set against an unimaginable run of playoff futility. Though one of just eight coaches in league history to win 200 games - an exclusive group that does not include all-time greats such as Chuck Noll, Bill Parcells, Vince Lombardi, and Bill Walsh - Schottenheimer is also the only one of those eight to fail to even play for a league championship, let alone win one. He always seemed to get the best out of his teams, right up until he couldn't.

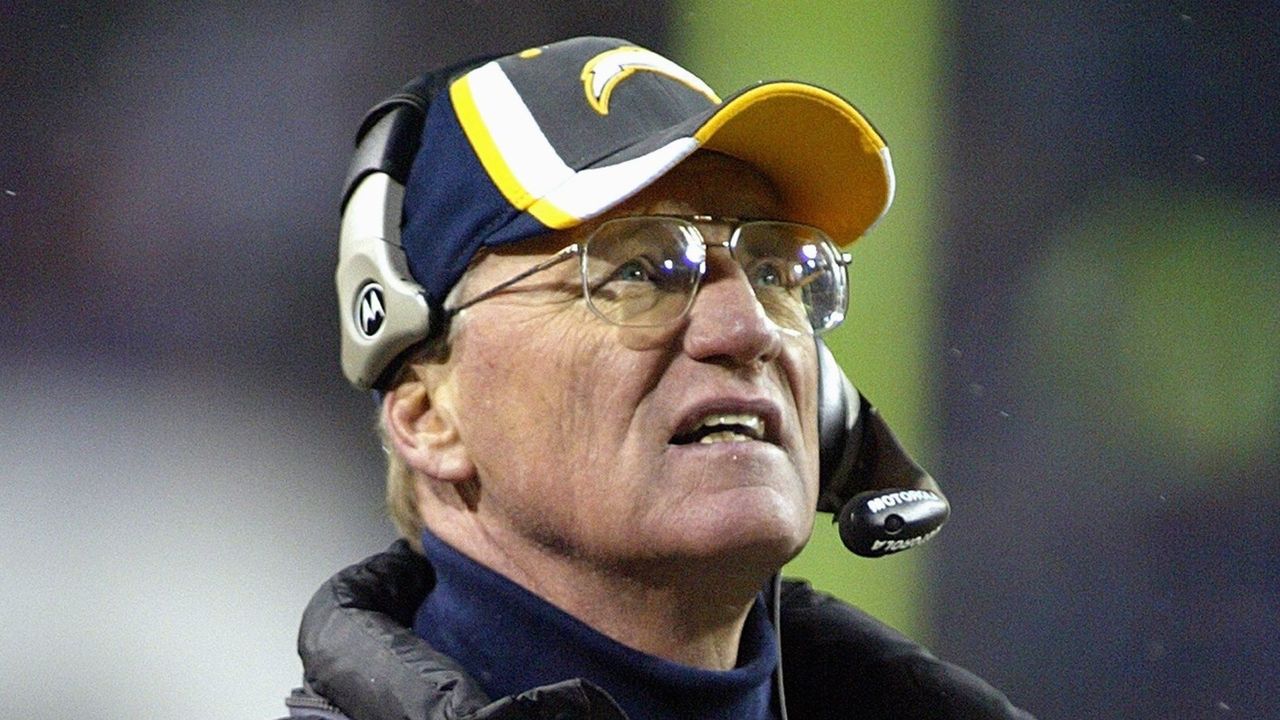

Schottenheimer-coached organizations in Cleveland, Kansas City, Washington, and San Diego won at least 10 games 11 times, had just two losing seasons, and posted a robust winning percentage of .613. And then came the playoffs, where "The Drive" by John Elway and "The Fumble" by Earnest Byner both happened at the expense of Schottenheimer's Browns. His Chiefs went 13-3 and earned the AFC's No. 1 seed twice in three years, only to get bounced in their first playoff game both times; after the second of those defeats, Schottenheimer revealed his vulnerability to that group of Kansas City reporters. He would later coach the Chargers to records of 12-4 and 14-2 - without winning a playoff game. And those are just some of the more famous examples.

Schottenheimer somehow went 5-13 in the playoffs and lost the last six postseason games he coached. He lost three games as a favorite of five points or more and was a staggering 0-8 in postseason games with a point spread of three points or less, according to Chase Stuart of Football Perspective.

So what was Marty Schottenheimer doing wrong?

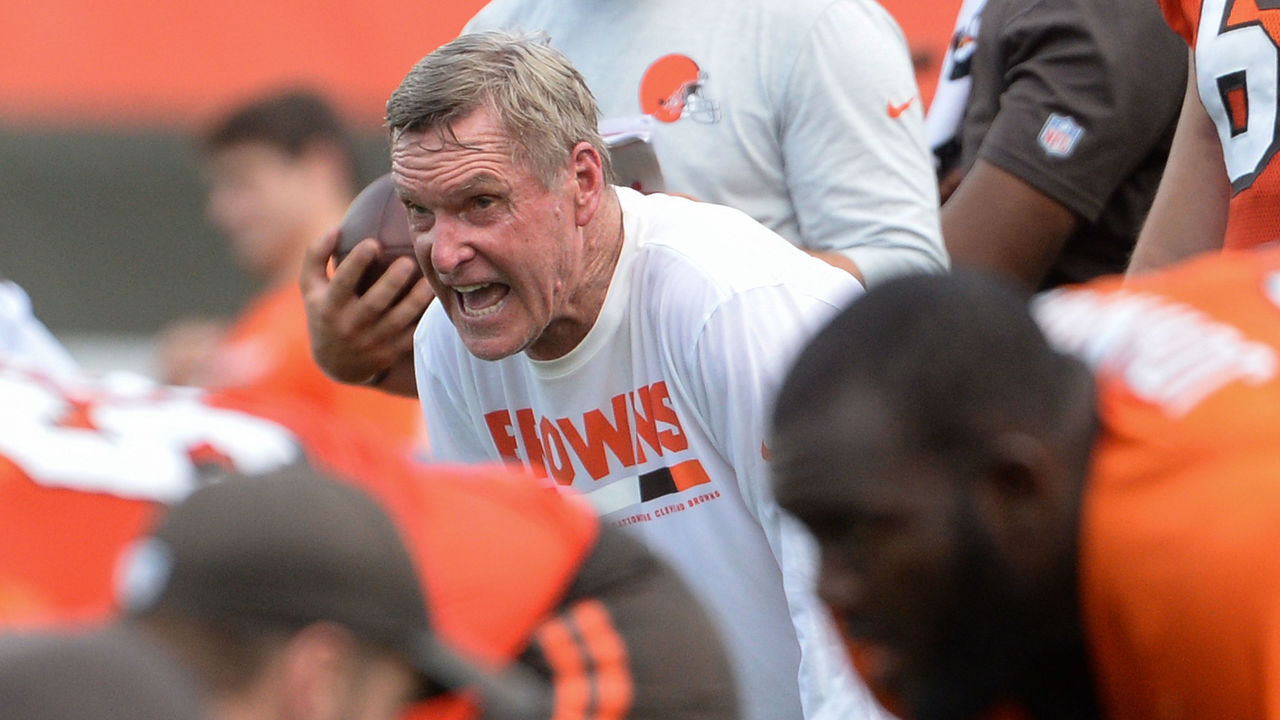

'A coach's coach'

As a football coach, Schottenheimer checked all the boxes. He was demanding. He was detail-oriented. He was a taskmaster who worked his assistants until the wee hours. He was a masterful motivator. He was a terrific teacher.

Rich Gannon, a quarterback who played four seasons for Schottenheimer in Kansas City, marveled at the way Schottenheimer could coach and teach pretty much every position, even though his background was as a defensive player and coach.

“He would carry around this thick playbook during the week, and he could pop into any position-group meeting and install the game plan," Gannon told me.

Al Saunders, an offensive assistant who coached under Schottenheimer for all 10 of his seasons in Kansas City, told me Schottenheimer had an extraordinary ability to communicate with his coaches and players.

"There was nobody that commanded a room as well as Marty Schottenheimer," said Saunders, who coached in the NFL at various stops for 35 years. "He was such a master of his ability to explain things and get his point across. He did such a phenomenal job of commanding the respect of the people he approached. Marty was a coach's coach."

Schottenheimer trusted players and looked after them as people. He allowed those players to stay in their homes, rather than a team hotel, on the night before home games - a concept Saunders at first thought was crazy. But Gannon said players appreciated the chance to spend that extra time with their families. Gannon also remembered a time during training camp when he approached Schottenheimer to tell him his young daughter was dealing with celiac disease.

"He just said, 'Go, and don't come back until everything's OK,'" Gannon said. "He had a really soft spot in his heart for family and kids. He wore his heart on his sleeve. He wasn't afraid to show his emotions, which, in a game full of tough guys, it speaks volumes about the inner workings of Marty Schottenheimer."

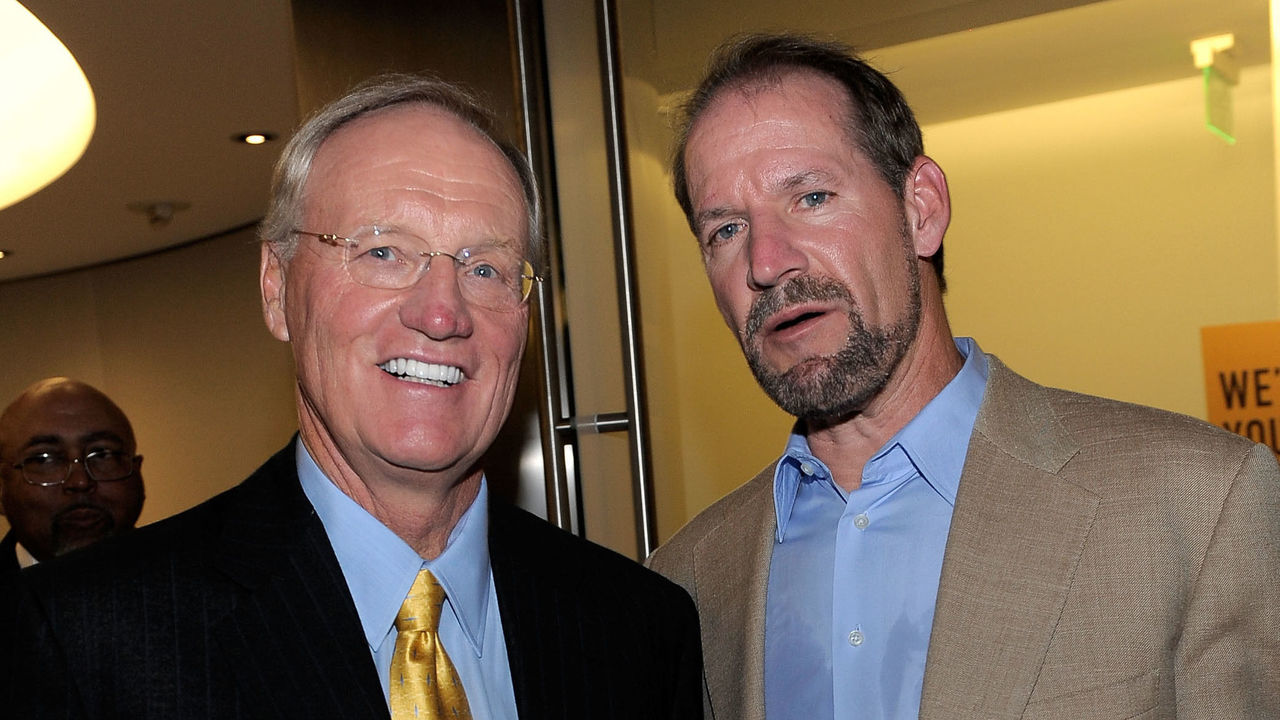

Schottenheimer even had an ability to identify young coaches with talent and potential. Four of his assistants - Bill Cowher, Tony Dungy, Mike McCarthy, and now Bruce Arians - have gone on to win the Super Bowl as head coaches. Black coaches like Herm Edwards and Marvin Lewis also entered the NFL coaching ranks via Schottenheimer's staffs.

Then there was Schottenheimer's coaching philosophy, which emphasized defense, special teams, and physicality. Offense, however, was largely about controlling the ball, avoiding turnovers, and winning the field position battle - a conservative approach of playing not to lose that came to be known as "Martyball."

Saunders joined Schottenheimer's Chiefs staff in 1989, and he was astonished when the head coach once said, "We play the game to kick the football." The goal, as Schottenheimer explained it, was to end each possession with an extra point, field goal, or punt.

"If we end each series with a kick," Saunders explained, "we'll win most of the games that we play because we're not throwing interceptions, we're not fumbling the ball, we're not turning it over. Marty was a field-position guy."

This strategy would seem completely foreign in today's NFL, where rules changes and data-driven approaches have prompted many coaches to accentuate the efficiencies of being pass-heavy and aggressive. But in the 1980s and 1990s, "Martyball" had its uses - particularly for the losing teams Schottenheimer took over, all of which he quickly rebuilt:

- Cleveland missed the playoffs 10 times in the 12 seasons before Schottenheimer got the job; the Browns reached the postseason in all four of his seasons as a full-time coach.

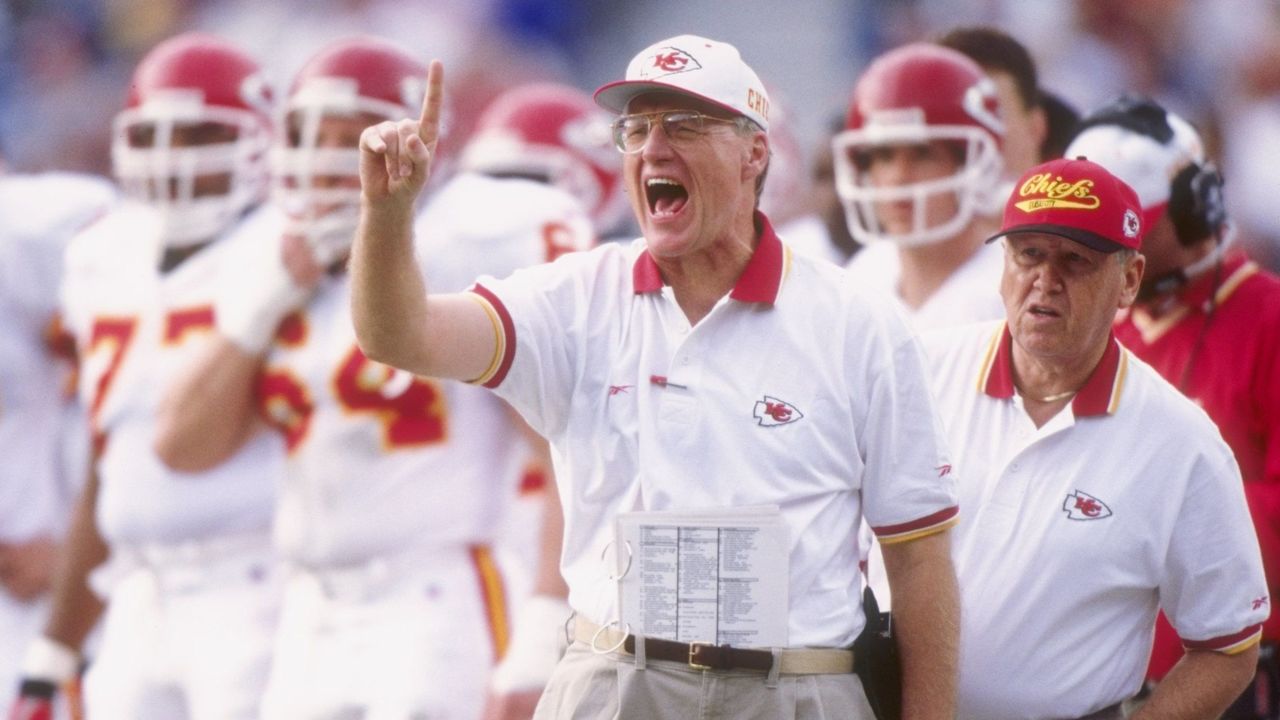

- The Chiefs had just one playoff berth in the 17 years before Schottenheimer; Kansas City advanced to the postseason in seven of his 10 seasons.

- Washington had just one playoff team in its eight pre-Schottenheimer years; it went 8-8 in his lone season with an awful roster, a tenure that ended because owner Dan Snyder is a nimrod.

- The Chargers had missed the playoffs six years in a row before Schottenheimer got there. He got them to the playoffs twice in the next five seasons.

It isn't easy to win with different teams under different management in different circumstances. Some of the league's best coaches couldn't pull it off. George Seifert, Mike Shanahan, Jimmy Johnson, and Tom Flores all won multiple Super Bowls, but their stints with other teams didn't go nearly as well. Even Walsh, a renowned innovator who built one of the sport's greatest dynasties, mustered a cumulative .500 record when he later went back to college to coach for three seasons at Stanford. But Schottenheimer? With four different teams?

"What he did was he built programs everywhere he went," Jeffrey Flanagan, the co-author of Schottenheimer's biography, "Martyball!," told 610 Sports' "Cody and Gold." "He is, to me, one of the greatest all-time coaches, ever. And he should be recognized for that."

The postseason can't be overlooked, of course. And Martyball had its limits. But Martyball also wasn't the only reason Schottenheimer's teams kept coming up short in the playoffs.

The playoff losses

There is much to consider about the games in which Schottenheimer's teams came up short, but three themes emerge, which we'll discuss later. For now, let's examine those 13 playoff losses.

1985 AFC divisional round: Miami 24, Cleveland 21 The Browns went 8-8 and won the AFC Central. They also led 21-3 in the third quarter before Dan Marino came back to beat them.

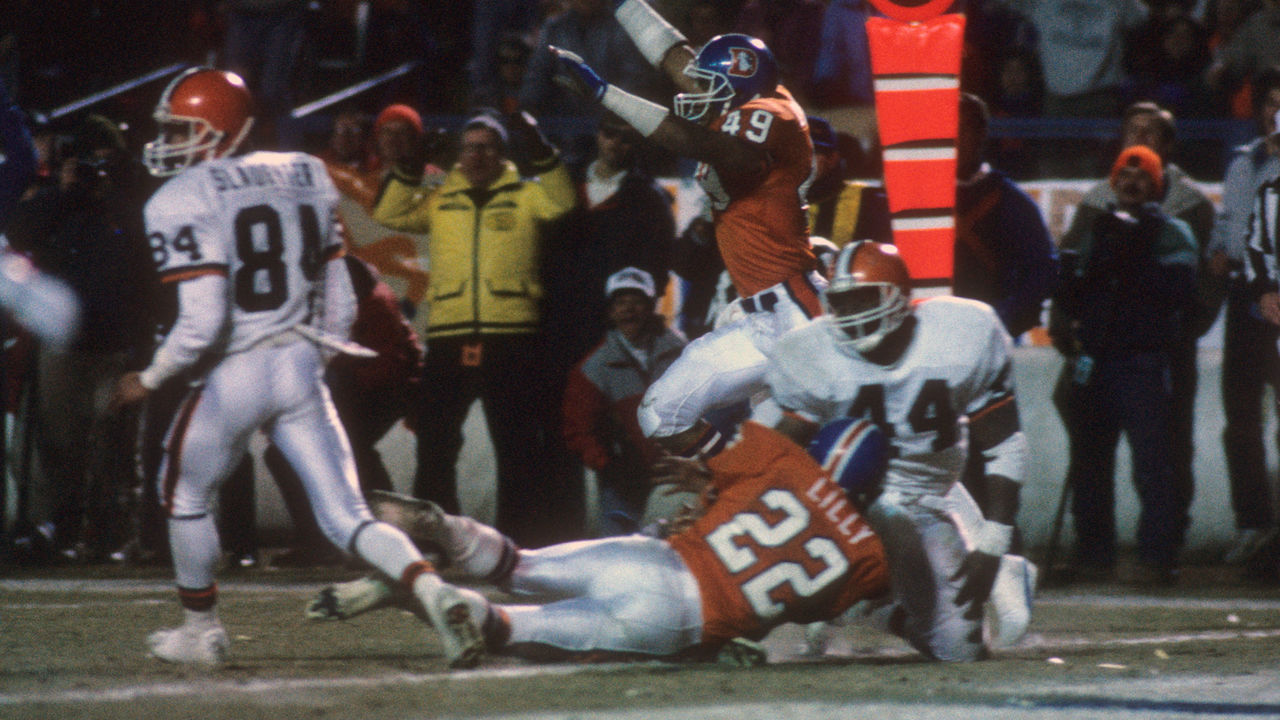

1986 AFC Championship Game: Denver 23, Cleveland 20 (OT) "The Drive" is the stuff of legend. It took 15 plays for John Elway to take the Broncos 98 yards, yet they faced a third down just twice. And while Elway was indeed brilliant, Cleveland didn't blitz him at all and even brought a lame three-man rush on a crucial third-and-18:

1987 AFC Championship Game: Denver 38, Cleveland 33 This time, the Browns came back from 21-3 down, and Byner fumbled just as he was about to score the game-tying TD with a minute to go. I mean, come on.

1988 AFC wild-card round: Houston 24, Cleveland 23 Schottenheimer assumed the OC duties and called the plays. The Browns even got back to the playoffs despite cycling through four starting quarterbacks due to injuries. Cleveland had the ball late near midfield while trailing by five, but someone named Mike Pagel threw an interception.

1990 AFC wild-card round: Miami 17, Kansas City 16 Even after Marino led a pair of fourth-quarter scoring drives to give the Dolphins the lead with 3:28 to play, Kansas City still had a chance. The Chiefs quickly drove to the Miami 26-yard line before a holding penalty knocked them back to the 37. Kansas City ran the ball on second-and-20 and wound up settling for a 52-yard field goal try by Nick Lowery. He missed.

1991 AFC divisional round: Buffalo 37, Kansas City 14

1992 AFC wild-card round: San Diego 17, Kansas City 0

1993 AFC Championship Game: Buffalo 31, Kansas City 13 To bolster an offense that kept losing to better QBs, the Chiefs traded for 37-year-old living legend Joe Montana and signed future Hall of Fame running back Marcus Allen in free agency. Both moves paid off. Kansas City won a pair of playoff games - including a road upset of an outstanding Oilers team - before stumbling against the Bills again. Montana suffered a concussion that knocked him out of the game early in the second half when the Chiefs were already down 20-6. Schottenheimer would never win another playoff game.

1994 AFC wild-card round: Miami 27, Kansas City 17 Montana and Marino were tied at 17 at halftime, but on back-to-back drives in the fourth quarter, Montana was picked off by J.B. Brown near the goal line and Allen had the ball ripped from his hands by Michael Stewart. It was the last game of Montana's career.

1995 AFC divisional round: Indianapolis 10, Kansas City 7 Journeyman quarterback Steve Bono had a brilliant regular season, but his limitations were on full display in frigid conditions. Bono threw three second-half interceptions before being yanked for Gannon, who guided the Chiefs into field-goal range with less than a minute remaining. Lin Elliott's 42-yard attempt sailed wide left - one of his three missed kicks that afternoon.

1997 AFC divisional round: Denver 14, Kansas City 10 Schottenheimer elected to start Elvis Grbac at QB even though Gannon led the Chiefs to five straight wins late in the season while Grbac was injured. So much went wrong: The Chiefs burned a pair of timeouts in the third quarter, including one after Grbac picked up a first down on a scramble and the Broncos' defense seemed gassed. A fake field goal on fourth-and-6 with holder Louie Aguiar trying to run for the sticks ended in disaster. And Grbac's headset malfunctioned on the failed final drive, when having another timeout or two might have helped.

2004 AFC wild-card round: NY Jets 20, San Diego 17 (OT) In overtime, San Diego marched to the Jets' 22, but they called three straight LaDainian Tomlinson runs to set up a 40-yard Nate Kaeding field goal in rainy conditions. As you might have guessed, Kaeding missed. The Jets won it on their next possession.

2006 AFC divisional round: New England 24, San Diego 21 This game is best remembered for Marlon McCree's fumble after he intercepted Tom Brady, the narrative being that McCree should have gone down rather than risk something catastrophic late in the game - especially because NFL Films cameras captured Schottenheimer before the game instructing another Chargers defensive back, Drayton Florence, to do just that.

The implication is that Schottenheimer did all he could to prepare for this scenario. But that's misleading: McCree's pick and fumble occurred with more than six minutes remaining; after it happened, the Chargers failed to stop the Patriots from scoring a touchdown, a two-point conversion, and a field goal. Schottenheimer also burned a timeout by challenging whether McCree had fumbled, which he obviously did. That timeout certainly would have come in handy when San Diego had to settle for a 54-yard field goal that Kaeding missed at the end of the game.

The quarterbacks

Quarterback play is the one constant in Schottenheimer's playoff futility. And it worked both ways; 10 of his 13 postseason defeats came against five Hall of Fame quarterbacks: Elway, Marino, Jim Kelly, Warren Moon, and Tom Brady. By contrast, Schottenheimer never got to work with an exceptional QB for any extended period of time.

Schottenheimer had four seasons with Bernie Kosar at the start of Kosar's career, two with Montana at the end of Montana's career, four with Drew Brees at the start of Brees' career, and one with Philip Rivers in Rivers' first season as a starter. Beyond that? A whole lot of ordinary dudes. According to Football Perspective's Stuart, Schottenheimer won games with 18 different starting quarterbacks, which is far and away an NFL record. If you don't count the victories from the three quarterbacks Schottenheimer won with most - Kosar (32 wins), Brees (30), and Steve DeBerg (28) - Schottenheimer still managed to win 110 games, as Stuart notes.

Just about any other great coach had a sustained run of success that coincided with having a terrific quarterback - even Parcells and Joe Gibbs, who both won at least 58% of their games with two different QBs, according to Stuart.

Schottenheimer's longest stay at any coaching stop was his 10 seasons with the Chiefs. Kansas City eventually acquired Montana and switched its offensive system to boost its passing game, but that experiment lasted for just two seasons. I asked Saunders, Schottenheimer's offensive assistant in Kansas City, if the franchise could have done more to acquire a better QB after Montana. The Bills' dominance of the AFC had just ended, and QBs like Stan Humphries, Neil O'Donnell, and Drew Bledsoe represented the AFC in the Super Bowl.

Saunders said it wouldn't have been that simple. Schottenheimer calibrated his teams to the kind of personnel he had to work with; any deviation from that risked sacrifices somewhere else.

"I think if Marty would have gone out and said we need to get such-and-such quarterback, his whole concept of football would have been compromised," Saunders said. "It's a whole building of thought, and that whole building of thought with Marty won a lot of games. He wasn't going to change.

"That wasn't what Marty believed. You won with the defense, you won with special teams, and offense will put us in a position that will win us a game 10-7. You couldn't have convinced anybody that was working with Marty or playing for Marty that we weren't doing the right thing at that time. We won."

In the playoffs, of course, it wasn't good enough. Saunders thinks that what Schottenheimer realized from those losses was that he had to take more risks, get more creative. His offense with the Chargers was much more dynamic, revolving heavily around the multi-skill ability of Tomlinson. But Schottenheimer only got one real shot during that 14-2 season, and then he was done. It seems fair to suggest that Chargers team gave Schottenheimer his greatest chance at winning a Super Bowl.

But Flanagan, the author of Schottenheimer's biography, said that Schottenheimer once told him that the 1993 Chiefs team - the one with Montana - had offered him his best shot.

"That team wasn't even that good," Flanagan told me. "But he said, 'I had the best quarterback in the history of football. That was my best chance, and it was because of Joe.' If it comes down to one possession, it's the quarterback, and he recognized that."

Principles, for better or worse

Schottenheimer coached with conviction and high personal standards, and at all four of his NFL stops, this both benefited and worked against him when it came to his relationship with management.

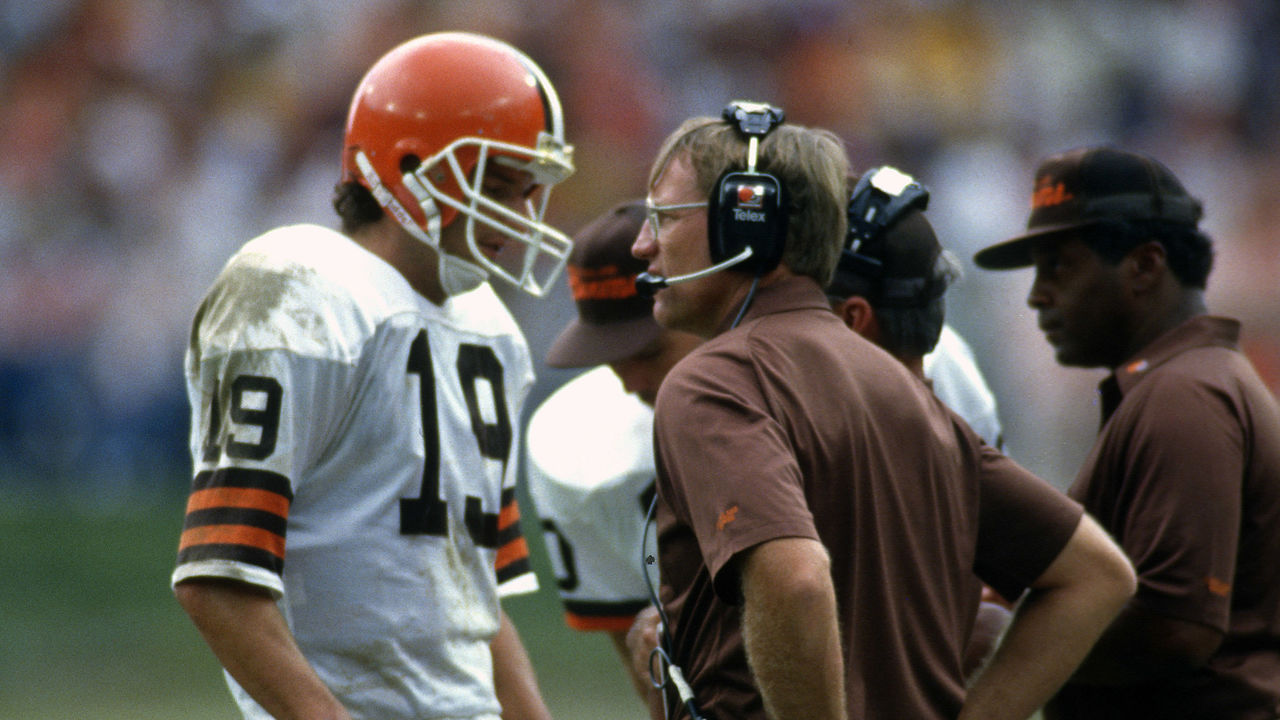

He was hired as the Browns' head coach midway through the 1984 season, at which point the team was 1-7. He had been the team's defensive coordinator, but he only agreed to take the head job if he could have it full time; as general manager Ernie Accorsi explained during an NFL Films documentary, Schottenheimer felt that the team would have tuned him out if he were just an interim coach. Owner Art Modell gave in.

After the 1988 season - in which the Browns made the playoffs with Kosar, Pagel, Don Strock, and Gary Danielson all starting at quarterback - Modell wanted Schottenheimer to hire an offensive coordinator and make other staff changes, including the reassignment of Schottenheimer's brother, Kurt, who was the special teams coach. There had been sideline communication issues and doubts about Schottenheimer's offensive play-calling prowess. But Schottenheimer not only refused Modell's demands, he resigned.

He was quickly hired by Kansas City, where he went 94-49-1 in his first nine seasons. But after 1998, when the Chiefs stumbled to a 7-9 finish - the first losing season of his career - and were by far the most penalized team in the league, Schottenheimer suddenly quit.

Saunders said the decision came as a complete shock to the rest of the coaching staff.

"He just said he doesn't think he's the right coach to turn it around," Saunders said. "He said he owes it to (owner) Lamar Hunt to step aside. He took that responsibility on himself."

In that NFL Films documentary, Schottenheimer described his decision to leave the Chiefs as "the biggest mistake I ever made in football." As soon as he said it, he began to fight back tears.

After two seasons away from coaching, Schottenheimer returned in 2001 as the head coach and general manager of Washington. Yet even after Washington finished 8-8 following an 0-5 start, Snyder wanted to hire someone else to handle the GM duties. The Washington Post also reported that Snyder wanted Schottenheimer to do more social events and to join him at dinner parties. Schottenheimer had no interest, and at the end of the season, Snyder fired him.

He quickly landed in San Diego, where he had the opportunity to build around Brees and Tomlinson. But his relationship with GM A.J. Smith was notoriously sour - and not just because Smith drafted Rivers and wanted to play him even though Schottenheimer preferred Brees. Things came to a head when Schottenheimer played Brees instead of Rivers - as Smith wanted - in a meaningless season finale in 2005, and Brees injured his shoulder. Brees was signed away that offseason by the New Orleans Saints, with whom he went on to have a Hall of Fame career.

Will never forget sitting with Marty Schottenheimer in San Diego in 2002, and listening to him explain how Drew Brees had so many of the qualities of Joe Montana, even though Brees' career was in its infancy and his performances were unsteady. He saw. He knew. Great coach. RIP.

— Seth Wickersham (@SethWickersham) February 9, 2021

Eventually, Schottenheimer and Smith weren't even speaking to each other, despite Schottenheimer's best efforts. Then, after that 14-2 season in 2006, five Chargers coaching assistants were poached by other teams, including both coordinators. Schottenheimer and Smith disagreed on their replacements, especially Schottenheimer's desire to hire his brother to be the defensive coordinator. The situation was untenable, but owner Dean Spanos sided with Smith and fired Schottenheimer, who would never coach in the NFL again.

Mistakes, circumstances, luck

Many of the same qualities that made Schottenheimer so good - his conservative approach, his fervent belief in doing things his way, his admirable value system, which could border on stubbornness - also contributed to his inability to win in the postseason.

But as an explanation for Schottenheimer's playoff shortcomings, that doesn't suffice. Football is a unique game that involves a lot of players, creating a lot of variables that can affect who wins and loses. Saunders adamantly believes Schottenheimer got the most out of just about all of the teams he coached, given their makeup.

"He won as many games as that group of players - offense, defense, special teams - would allow him to win," Saunders told me. "You get in the playoffs, and all of a sudden you find a great football team that played better. I really believe that. He went as far as he possibly could.

"Marty took his teams so far that people expected more, but in reality, they had no more to give. The 14-2 team in San Diego was probably the team that was a Super Bowl championship team, and it just unfortunately didn't make it in that game.”

Saunders' theory might seem pat, but considering the quarterbacks Schottenheimer often had to work with and the brevity of his tenures at three of his four of his coaching stops, it's at least somewhat plausible. There is also the luck factor. It might be a platitude to suggest coaches and teams make their own luck, but that's not always the case - especially not in a sport with so many variables and such small margins. Take Bill Cowher and Andy Reid.

Both Cowher and Reid are thought of as great coaches, and they both possess a Super Bowl ring to cement the argument. But both also had reputations for staggering losses in the playoffs - at least until they didn't. For Cowher, things finally changed with the arrival of quarterback Ben Roethlisberger; for Reid, Patrick Mahomes helped shift the storyline.

Even then, it's not that simple. Cowher's eventual champion Steelers in 2005 benefited from Carson Palmer's knee getting blown out in the first quarter of their wild-card round win at the Cincinnati Bengals. A week later, Jerome Bettis fumbled at the goal line as the Steelers tried to run out the clock, and the only thing that prevented a monumental collapse against Indianapolis was Roethlisberger's miraculous shoestring tackle of Nick Harper. In that playoff run, the Steelers also avoided the New England Patriots, who have owned them for the last 20 years. Cowher was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2020. Would that have happened had he not won that Super Bowl?

And what about Reid? As dominant as his Chiefs have been offensively, let's not forget that they trailed the San Francisco 49ers 20-10 with a little more than seven minutes remaining in Super Bowl LIV. That game changed when Mahomes connected with Tyreek Hill for 44 yards on third-and-15. But what if something had gone wrong? The difference in the tenor of the "What is Andy Reid's legacy?" conversation really is that narrow.

Schottenheimer certainly made his share of mistakes, but he was also bitten hard by a stupendous run of bad luck and an unfortunate swirl of events. What if Byner holds on to the ball, or Lowery or Elliott or Kaeding make any of those kicks? What if Schottenheimer had a better quarterback for a longer period of time? What if he stayed in Kansas City? What if A.J. Smith was easier to get along with? What if, on that backbreaking third-and-18 during "The Drive," the shotgun snap that bounces off of motioning wideout Steve Watson doesn't ricochet right into Elway's hands?

These potentially legacy-altering scenarios are endless. Meanwhile, Marty Schottenheimer, winner of 200 games with four teams, still isn't in the Hall of Fame.

"I don't know that you can categorize Marty's not reaching a Super Bowl," Saunders told me. "I don't know that there’s a way to define that. Some things just happen."

What was Marty Schottenheimer doing wrong? Never mind. He was a hell of a football coach, and that's good enough.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.