Inside Oakland's painful goodbye to the Raiders and Warriors

OAKLAND - The Golden State Warriors hadn't won a game in 12 days or made the playoffs for 12 years when, in the first week of March 2007, they strode onto the Detroit Pistons' home court with a glint in their eyes that Paul Wong thought he could discern from 2,400 miles away. Yet another losing season was square in the players' sights, but something about the way they looked on TV ran counter to the acquiescence that might be expected of a team that was 26-35. They seemed confident that they could engineer a turnaround together. Perhaps it was time for other people to start believing, too.

For decades before the Splash Brothers delivered a dynasty to the Bay Area, doubt in the Warriors was their fans' default state. Wong joined their ranks in 1979 as a 6-year-old new immigrant from Burma who didn't yet speak English. On the final day of the 1981-82 season, with the Warriors needing to beat Seattle to reach the playoffs, he stayed awake past midnight to watch on tape delay as they lost by one point. In 1994, at the first postseason game Wong got to watch in person, Charles Barkley dropped 56 points for the Phoenix Suns to sweep the Warriors from the first round.

During a big defeat in the down years that followed, Warriors play-by-play announcer Bob Fitzgerald turned to his broadcast partner, retired NBA guard Jim Barnett, and posed a question of perpetual significance: Where, exactly, does a player look for motivation when they're getting blown out?

Barnett's reply stuck with Wong. Back in his day, the broadcaster said, he would fix his gaze on someone in the stands - a personal guest, a child in a jersey - and commit that night to playing for them.

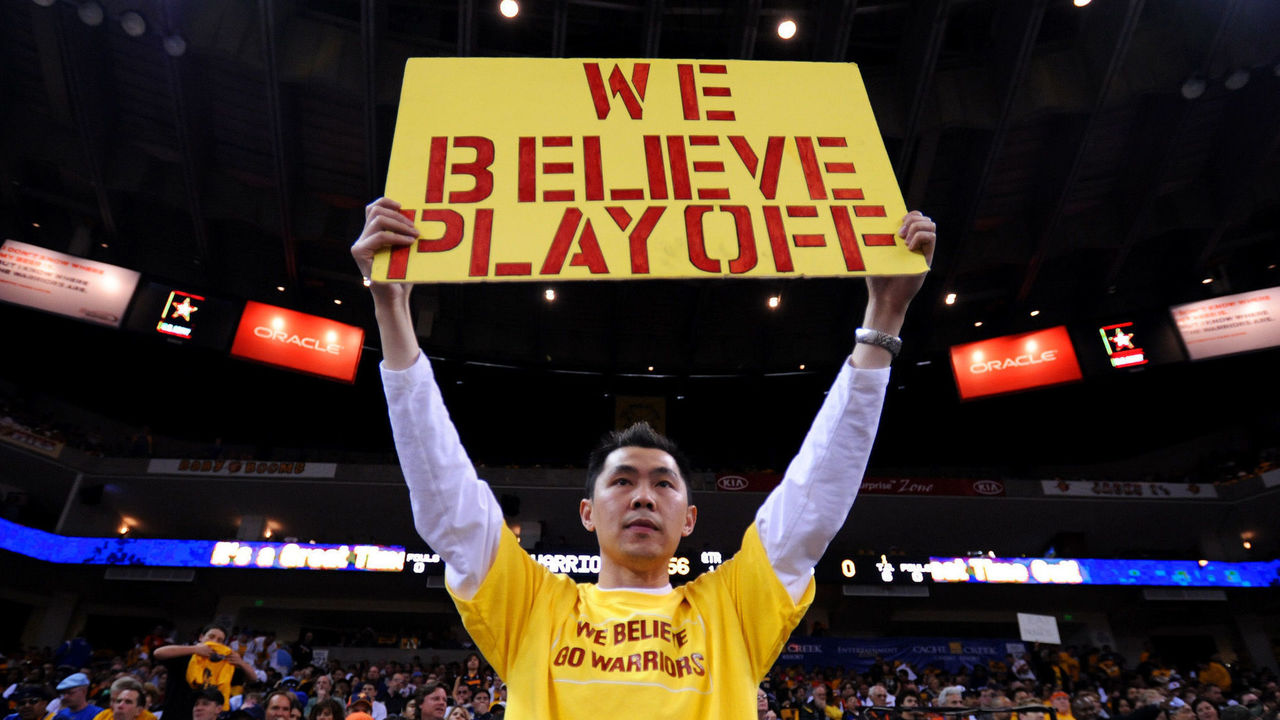

On March 5, 2007, Golden State beat Detroit, the best team in the Eastern Conference, 111-93 and flew home for a matchup two nights later with Denver. Wong attended that game with a sign on which he'd printed two words: "We Believe."

The premise was absurd - right up until it wasn't. When Wong distributed duplicates of his placards on Oakland street corners and inside Oracle Arena, some people accepted, then promptly dropped the offering on the ground. Only drugs, a few onlookers said, could have emboldened his delusion that the Warriors could win their way into the playoffs.

Printing the signs had cost Wong several thousand dollars, so he dusted off any that were discarded and returned them to his stack. Soon, he started to find willing takers in a comparatively optimistic segment of the market: kids. And within a month, after 12 wins in 17 games vaulted the Warriors from 12th place to eighth in the Western Conference, team staffers arranged to meet with Wong at the Hawaiian barbecue restaurant he owned in nearby Alameda. They asked if they could repurpose "We Believe" as an official slogan if the Warriors held on to their playoff spot.

Wong gave his blessing on one condition: The team could use his mantra on T-shirts if they were handed out for free.

The highlights of the Warriors' subsequent playoff run were timeless. Baron Davis' posterization of Andrei Kirilenko in the second round. The stunning six-game upset of the 67-15 Dallas Mavericks that got Golden State that far. And a memory from before each of those milestones that Wong won't soon forget: the realization, as he entered Oracle ahead of Game 3 against Dallas, that every seat was adorned with his cri de coeur.

"I choked up," Wong said. "For me to walk into a stadium where every single attendee went home with that shirt, how incredible is that?"

In October, 12 years on from the fulfillment of Wong's show of faith, a new Warriors season tipped off not in Oakland but in San Francisco, kickstarting the team's passage from one NBA era to the next. Kevin Durant is rehabbing his torn Achilles in Brooklyn. Klay Thompson and Steph Curry are confronting long injury layoffs of their own. And Golden State is no longer the league's singular franchise, reduced instead this season to dreaming of a future return to glory.

In a way, it's fitting that the Warriors are assuming this novel identity - temporarily hapless contender - in a new home. They now play at the glitzy, $1.4-billion Chase Center, a traffic-snarled drive across the Bay Bridge from the building formerly known as "Roaracle."

What did Oakland retain in the move? A legacy of supporting the Warriors through lean decades and a long-awaited heyday. Stories that bring this fidelity to life, like the genesis of "We Believe." Pride, off the court, in the city's ethnic diversity and the historical propensity of its underdog residents to work hard. And the awareness of what it's like to lose the symbiosis between a place and its team - the relationship that forms when many people watch sports and see in the players a reflection of themselves.

"Their character as a team represents a lot of the East Bay: the never-die (mentality), the fight in us," Wong said. "When you look at a player like Draymond Green, that's Oakland. It's a personality that they're taking away."

Welcome to Oakland in fall 2019, where the nightmarish sensation of a pro team relocating - the departure of the rare business around which thousands of locals orient a significant portion of their lives - is doubly raw. Just as the Warriors have packed up and left, the NFL's Raiders are getting set to depart. Once this season ends they are bound for Las Vegas as soon as 2020, the conclusion of owner Mark Davis's maneuvering to escape Oakland's aged Coliseum.

Relocation is a recurring fact of life in more than a few Big Four cities. St. Louis lost baseball's Browns (now the Baltimore Orioles), basketball's Hawks, and football's Cardinals and Rams. Two NBA franchises (the Rockets and Clippers) and the NFL Chargers left San Diego. The NBA and MLB have each, at different times, jilted Milwaukee and Philadelphia; the same goes for Kansas City, which also lost an NHL franchise.

But not since 1995, when the Raiders and Rams uprooted simultaneously from Los Angeles, has any city lost multiple teams in such close succession. After several years of fruitless stadium negotiations and grassroots campaigns to keep the Warriors and Raiders, Oakland's sports fans are learning how much those losses hurt.

"We're in the throes right now of trying to figure that out," Oakland sports historian Paul Brekke-Miesner said. "It's going to be such an incredible hole."

When dyed-in-the-wool fans across Oakland think about life without the Warriors and Raiders, a constellation of common concerns and convictions starts to emerge. They fear that basketball crowds at Chase Center won't be nearly as diverse or exuberant as at Oracle. They detest that their dynastic team was handed on a platter to an archrival city. They believe that since the Raiders' black-and-silver mystique originated in Oakland, Davis should find another name to use in Vegas. They understand the economic and aesthetic allure of moving to a lavish facility, but they know as well as anyone that these moves have an emotional toll.

The pain is theirs to share, but it's also atomized. When teams leave, there are many faces of grief.

These ones include Lloyd Canamore, 57, whose diehard Warriors fandom was born from a teenage gig selling peanuts and hot dogs at home games in the late '70s. He lives eight miles from the arena, in a house that a friend painted blue and gold as a goodwill gesture after two of Canamore's brothers died not long apart. Visitors duck under a replica championship banner to get to the door. When the rapper Bizzle wrote a paean to the team called "Warriors," he recorded his music video - complete with a cameo from Curry - on Canamore's front steps. The Warriors mean everything to him, Canamore said, and it has been awful to see them go.

They include Mark Acasio, 52, a landscaper, an ordained minister, and the Raiders superfan known as Gorilla Rilla. In his signature furry black mask and bodysuit, he's a fixture at the front of the Black Hole, the famously fervent section of the Coliseum where he once caught an errant pass from Houston quarterback Matt Schaub. (Al Davis himself sent word through security that Acasio could keep the ball.) NFL commissioner Roger Goodell joined him in Row 1 for a Thursday night rivalry game against Denver in 2012. He has officiated the weddings of couples he met through Raider Nation and struck up friendships at tailgates with people from around the world. People all over the East Bay wake up excited on game day, Acasio said, and it will be deeply sad when that spark is gone.

They include Wayne Mabry, 63, the Raiders superfan known as Violator, a persona it takes two hours to assume each week. He dons 10-pound boots, a leather headpiece and motorcycle pants, face paint, shoulder pads, and a jersey with protruding spikes. He drives seven hours north from Moreno Valley, California, for every home game, never failing to admire the sight of the Coliseum - "hallowed ground" - as he exits right off the Nimitz Freeway. It has been bittersweet to sit through Sundays this season, he said, expecting the infectious, intimidating energy in the stadium won't translate to tourist magnet Vegas - and knowing it will never invigorate Oakland again.

"It's going to leave an empty hole in the city," Mabry said.

The Raiders have done this to Oakland before. Al Davis whisked the franchise to L.A. in 1982; the team won a Super Bowl the following year and stayed in SoCal for another decade. But the Raiders' aura is inextricably connected to their original and present home. "Just win, baby," is a product of Oakland, as were the John Madden-coached teams whose blood feud with Pittsburgh gave malicious meaning to the motto in the '70s. Quarterbacks Ken Stabler and Rich Gannon won MVP awards there on either side of the L.A. years. "Oakland and the Raiders," Hall of Fame defensive back Ronnie Lott once wrote, "are synonymous with each other - a compound word."

"Oakland has been a tough, working-class port and railroad town over the years. It's no accident that the Raiders have that tough image that they've always had," Brekke-Miesner said. "What they are is Oakland. You can't just rip them out of Oakland and everything is the same."

Like the Raiders, the Warriors' backstory includes a transitory chapter: The team was founded in Philadelphia, based in San Francisco from 1962-71, and never explicitly branded itself an Oakland entity. But the bulk of Golden State's history was crafted in The Town. The 1975 NBA title. Sleepy Floyd's 39-point half against Magic Johnson and the Lakers. The span of 35 seasons that yielded only six playoff berths, and the five seasons that culminated in as many runs to The Finals. The Warriors' last 343 games at Oracle were played in front of a sellout crowd.

Thirty percent of Warriors season-ticket holders didn't renew their seats this season, opening the door for a new segment of Bay Area fans to support the team up close. The demographics of San Francisco and Oakland suggest that in the years to come, Chase Center crowds will differ, generally, in two ways from the throngs that used to pack Oracle: They'll be more affluent and they'll be whiter.

| U.S. Census Bureau data (2018) | OAK | SF | U.S. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 429‚082 | 883‚305 | 327‚167‚434 |

| White pop. % | 36.7 | 47.2 | 76.5 |

| Black or African-American pop. % | 24.3 | 5.3 | 13.4 |

| Asian pop. % | 15.9 | 34.2 | 5.9 |

| Hispanic or Latino pop. % | 27.0 | 15.3 | 18.3 |

| Median household income | $63‚251 | $96‚265 | $57‚652 |

The latter distinction troubles Oakland civil rights attorney John Burris, a longtime Warriors fan who told The Undefeated earlier this year that the relocation to San Francisco would inevitably curtail the number of black people who attend home games. That means something, Burris believes, in a league where about three-quarters of the players are African-American, according to The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports.

In Oakland, "you didn't have this feeling that I did (at other NBA arenas): that there were black men performing just for white, well-to-do (people)," the 74-year-old said in an interview. "To me, it was important and is important that the black community itself, the African-American community itself, shares in their skill level and shares in observing them and being present and cheering them on."

On a personal level, Burris said, the Warriors' move leaves a hole in his heart. He'll go to far fewer games than the 20 he'd attend each year in Oakland, and his distance from the team will feel greater than the width of San Francisco Bay. Oracle was a joyous, uproarious venue, he said. About a month before the home opener at Chase, he encountered at the grocery store a friend he'd often see at games. They took a minute to lament the end of the good times they shared.

"That's yesterday's news," Burris said.

Brekke-Miesner, 74, has his own reasons for feeling stung. He bemoans the irony of the Warriors and Raiders departing a city that has raised so many talented athletes: Frank Robinson and Bill Russell, Rickey Henderson and Joe Morgan, Jason Kidd and Gary Payton, Damian Lillard and Marshawn Lynch. Money seems to matter over everything when a team skips town, he said. It's an aching lesson, and the ache lingers.

A couple of years ago, after the Raiders' plan to move to Vegas was set in stone, Brekke-Miesner ran into an acquaintance at a downtown tapas restaurant. The man hailed from a Raiders family. His dad took him to games and tailgates as a little kid. He passed down his zeal for the team to his two sons. The boys were 9 and 12 when they heard about the relocation, and in the course of processing the news, they started to cry.

"This is family roots. This is what we do," the man told Brekke-Miesner, tearing up himself. "I don't believe that owners really understand how deeply rooted we get with our professional teams. And then they leave."

Two Saturdays ago in Oakland, the day before the Raiders played at the Coliseum for the first time in seven weeks, Mark Acasio - the landscaper in the gorilla suit - spun on his heel and found himself face-to-face with Wayne Mabry, outfitted for the afternoon in his faux linebacker garb. The men grinned and greeted each other with a hearty bro hug.

"Old soldiers," Mabry said, sizing up his longtime Black Hole contemporary.

Acasio and Mabry - Gorilla Rilla and Violator - were holding court on the gym floor of a community center one freeway stop south of the football stadium, slapping backs and happily obliging a continual stream of photo requests at a gathering of their team's most devout followers. The Raiders Fan Convention is a traveling production; hundreds of Al Davis disciples flocked to stops in Seattle, San Diego, and Las Vegas in the past few months. This event was billed as a return to roots: a reunion and weekend kickoff party in the city "where it all started."

Black and silver clothing was ubiquitous, but that guideline allowed ample space for sartorial flexibility. People wore ghoulish masks, biker vests, and butterfly wings. Jerseys paid homage to a host of favorite players through the years: Fred Biletnikoff, Jim Plunkett, Amari Cooper, Marshawn Lynch. More than one man came dressed as a pirate. On stage at the front of the room, a rapper laid down a Raiders-themed rendition of "Old Town Road" that included a shoutout to the Hall of Fame punter Ray Guy. Plunkett, the featured celebrity guest, signed autographs all the while in a nook outside the gym, away from the noise.

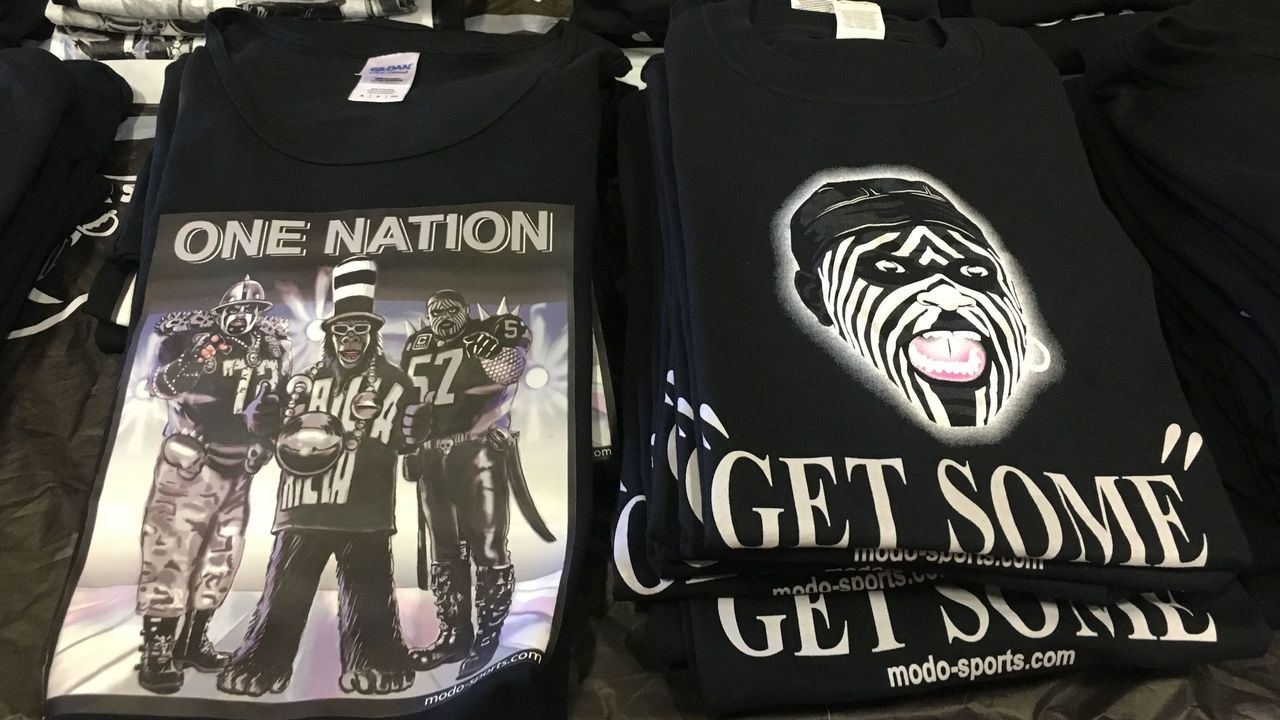

As Acasio and Mabry chatted near a table covered in T-shirts, on sale for $20, that bore their likenesses, an imposing, goateed man wearing a sombrero, silver football pants, and a No. 69 jersey with "Señor" on the back walked over to say hello. "The circle is complete," Mabry said, as a fourth man swept in, phone in hand, to ask for a photo.

"Señor," or "Señor Raider," is Sean Camacho, a former U.S. Marine of Mexican heritage who adopted the moniker in tribute to the Raiders' short-lived original nickname, the Señors. Camacho used to live in Southern California, but the grind of flying in for home games - he and Mabry sit together in the front row at the 50-yard line - helped inspire him to relocate to Hayward, fewer than 10 miles from the Coliseum. Raiders fans are family, he said, and Oakland is their home, making everywhere else the logical opposite: "not home."

Up on stage, the event DJ paused for a minute to recall the very first Raiders Fan Convention, held in Oakland on a much smaller scale 11 years earlier. A few friends, he said, had "just decided to get together and" - here he waited a beat - "love each other. And now look at what it's grown into."

The lovefest spilled into the following morning, when many thousands more fans - bearing grills, lawn chairs, and loudspeakers; craving barbequed meats and a win over the Detroit Lions - occupied huge swaths of the parking space that encircles the Coliseum. Tents, neatly organized into long parallel rows, shielded much of the crowd from the sun. Beer and discussion flowed as others milled about the lots, taking in the spectacle of the Oakland Raiders tailgate scene's last hurrah.

There was a lot to see. An inflatable Darth Vader figurine perched atop one tent, standing guard over a flat-screen TV tuned to highlights on CBS. Nearby, Raiders superfan (and Hulk Hogan impressionist) Malkamania shouted into a microphone during a live taping of a fan-run podcast. Clutching a football, two men in Derek Carr jerseys stood 50 yards apart and lobbed deep bombs back and forth. An interloper in a San Francisco 49ers jacket dropped a slip of paper on the ground, eliciting a playful heckle from the curb: "That's why you don't belong here!"

Camacho strolled by, pausing for a few selfies on his way to the Black Hole's outpost at the back of the far lot. The image of a hooded reaper, superimposed onto a banner along with photos of Camacho, Acasio, and Mabry, heralded entrance to the enclosed area, where visitors clustered around picnic tables with hot dogs and Corona cans. People crowded the adjacent walkway, snapping photos and cheering a Raider Nation-branded limo's attempt to inch in the direction of the stadium. A little later on, everyone at the tables raised their drinks and sang "Happy Birthday" to Acasio, who'd turned 52 a few days earlier.

"Wait a minute," a man in a Charles Woodson jersey said from the walkway. "It's my motherf------ birthday!"

That afternoon's Raiders-Lions game was telecast on FOX, whose cameras cut repeatedly to Acasio and his fellow Black Hole denizens. His section went wild in the second quarter, when Raiders running back Josh Jacobs leapt into their ranks to celebrate a touchdown plunge. They exulted again with two minutes to go, when receiver Hunter Renfrow toe-tapped in the end zone for a tiebreaking score. Oakland won 31-24, and after time expired, head coach Jon Gruden rushed toward the Black Hole to get mobbed.

The jubilation ebbed as the Coliseum cleared. Some spectators lingered in the parking lot for another drink, while many more continued toward a footpath that leads to a transit station and the street. Somewhere in the pack, two men cut through the hum of murmured conversation with a chant: "F--- Las Vegas!"

In the coming months, how will Oakland fans process all of this change? The disappearance, after three more regular-season home games, of Raider tailgates from the Coliseum grounds? The likelihood - a consensus among this subculture's fiercest adherents - that opposition fans will neuter the Raiders' home-field advantage in Vegas? The type of stirring scene that unfolded at Chase Center the night after the Lions game, when the Warriors wore San Francisco retro uniforms and withstood 39 points from Oakland's own Damian Lillard to stun Portland? The possibility, floated by MLB commissioner Rob Manfred, that the Athletics, too, might leave town if they're unable to finance the construction of a new stadium?

Sports grief can assume any number of forms. One manifestation already overcame Ray Perez, a former Raider Nation stalwart known as Dr. Death. In November 2016, Sports Illustrated featured a photo of Perez on its cover. That Christmas Eve, he attended his final game at the Coliseum, a Pyrrhic victory over the Colts in which a sack broke Derek Carr's fibula. Three months later, on the day that NFL owners approved the Raiders' relocation to Vegas, Perez opened his iPad and live-streamed the retirement of his persona, crying as he slammed ownership for taking for granted and abandoning its community of supporters.

"They're dead to me. Anytime I see somebody wearing a Raider emblem, I just scowl," Perez, 31, said in an interview. "My sentiment now is I just want nothing but the worst for that franchise."

United in their roles as Raider Nation talismen, Gorilla Rilla, Señor Raider, and Violator's future plans fall along different points of a spectrum. Acasio will keep his tickets when the team moves, steadfast as ever in his desire to "spread the Raider love." Camacho hasn't committed to traveling to Vegas, convinced as he is that the atmosphere won't be anywhere close to the same. Mabry won't tailgate under the beating Vegas sun, but summarizes his intent to travel to some home games thusly: "I'm a Raider fan till they put me in the box, and then after that."

Back in Oakland, Brekke-Miesner, the historian, has soured on pro sports in recent years, a perspective in line with the dispiriting message he feels the business has sent to fans: "Don't get too attached."

Wong, the progenitor of "We Believe," works these days as a realtor, a world in which he has styled himself the Dub Agent. He has sworn to never wear San Francisco-branded Warriors gear; "The Town" remains his insignia of choice. And yet the move across the bay didn't sever his allegiance. When Wong was 5 years old in Burma, he got the chance to attend a single soccer game with his dad. He treasures that memory for the same reason he came to consider Oracle a second home - the place where for 22 years he spent wonderful nights with his wife, Mai, and their sons Jordan and Tommy, savoring the heights the Warriors finally reached and his unique proximity to that success.

"I feel we're sort of part of the Warriors' history," he said.

Histories are forged through stories, and so here is one more, about a birthday gift to a 9-year-old girl and the lifetime of fandom that followed. Leslie Sosnick's parents, Peter and Sylvia, were sports-crazed. They cared about the Raiders and the 49ers. They kept tabs on the A's and the San Francisco Giants. In 1962, the Warriors moved to San Francisco from Philadelphia, and that season the Sosnick clan adopted its newest and dearest pastime. Late timeouts in close games doubled as tutorials in basketball strategy: Peter would turn to his daughter, flatten his palm, and trace the play he expected the Warriors to run. Sometimes they sat courtside, where the hard-nosed guard Al Attles - Leslie's first favorite player - once dove headlong over her for a loose ball.

The Warriors moved to Oakland, and Attles was hired as head coach, and in spring 1975 Leslie was by her parents' side as Golden State swept the Washington Bullets for the NBA title. Three years later, Peter passed away; Leslie took over his season tickets. She was there for the down years, each and every one, suffering but loving it, contributing to a home-crowd din that remained stubbornly, pleasantly insane. Sylvia died in 2000, and Leslie retired early. In 2015 she celebrated another championship with the sense that her parents were there, too, watching on each of her shoulders.

Leslie, now 65, resided in the Oakland Hills for some of this time. She ran into Steve Kerr on a couple of walks and, for a few years, lived next door to Andre Iguodala. Eighteen months ago, she and her husband, Ron Saxen, moved an hour east to Brentwood and gave up her family's season tickets of 54 years, squeezed out by price increases and aware that relocation in the other direction loomed. They'll go to some games at Chase Center, but mostly she'll tune in on TV, texting Saxen, elsewhere in the house, score updates anytime he finds the live action too stressful.

With Curry and Thompson shelved, she knows this season will be a struggle, yet still, she believes. Soon enough, she figures, she'll get to reprise her new tradition of blocking off her social calendar from April through June. Curry will return to run the offense, which she likens to watching a beautiful dance. She'll continue to appreciate the tone Kerr sets, empowering players to speak out on social issues and be themselves. She'll reflect on how, at Oracle, she had a seventh-row seat to the entire careers of legends - Bird, Magic, Jordan - and marvel at her good fortune.

Chase Center will be unfamiliar, and her heart will wish that the Warriors stayed in Oakland. But they'll still feel like family, and that is all the assurance she needs.

"What can I say?" she said. "I'm loyal."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.