New England was a pitiable franchise until the 2001 Patriots went on a roll

Following our recent series on the best teams never to win a championship, we're flipping the concept. This series will examine a selection of the most unlikely teams to reach the mountaintop. These teams can be ones that got hot at the right time, or those who belong to franchises that have not often tasted the Champagne of champions. Previous entries covered MLB, NFL, NHL, NBA of the 1970s and 2010s, and NCAA football.

The suggestion reads like revisionist history. The twice-dynastic Patriots, unlikely champions? Today's college freshmen have never lived in a world where New England suffered so much as a losing season.

We call that world the 20th century. Back then, the Pats' rare Super Bowl trips were fruitless, producing one 46-10 thumping from the generationally fearsome 1985 Bears and a 35-21 loss to the 1996 Packers. Worse, they didn't exceed five wins in a third of their first 30 NFL seasons of 14 games or more. In several cases, the Patriots fielded squads that rivaled, say, the recent Browns for ineptitude.

Two telltale stats illustrate the depths to which this franchise once slumped. The 1990 Patriots went 1-15 and posted the NFL's second-worst point differential (-265) across a 16-game season. The 1981 Baltimore Colts, owners of the all-time low at -274, managed to win twice that particularly hideous year - in their season opener and finale, both times over a New England team that was also 2-14.

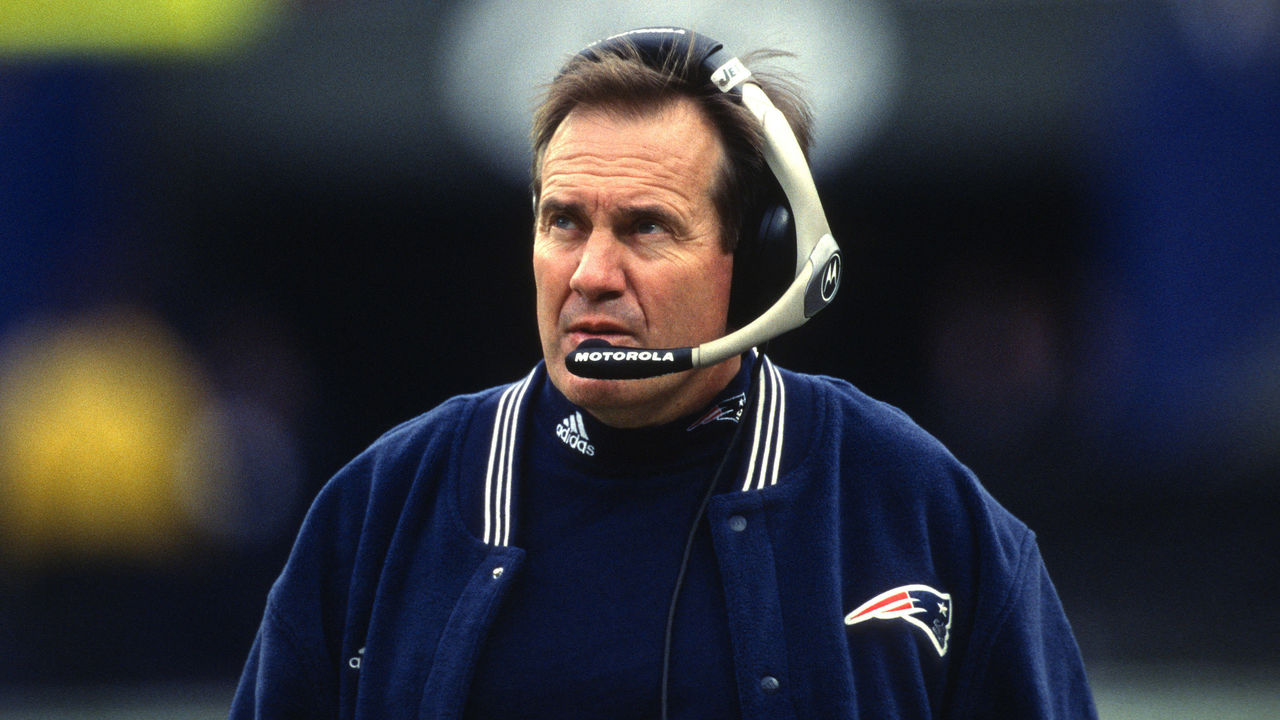

Last week, theScore's Dom Cosentino identified the 2002 Super Bowl champ Buccaneers as the NFL's supreme outlier. Inferiority is Tampa Bay's everlasting default state; that team, and only that team, won it all nevertheless. The 2001 Patriots were no outlier, as the entire Bill Belichick era attests, but only with 20 years of hindsight.

New England's ascent had to start somewhere, and the origins of those '01 Pats were humble. In the face of nonexistent preseason expectations, they rallied to a division title, benefited - Raiders fans, look away - from the infamous reversal of a called fumble on the field, and bucked the weight of a difficult few decades by beating the best offense ever assembled, all as their No. 1 quarterback evolved into a star.

It just wasn't the guy they expected to fill the role.

The run-up to New England's first Super Bowl triumph began in earnest on March 7, 2001, when team owner Robert Kraft signed his franchise signal-caller to a 10-year, $103-million contract. The deal was the most lucrative in NFL history, a vehement endorsement that the player would be the Pats' go-to QB for life.

"Quarterbacks like this come around once in a lifetime," Kraft told Sports Illustrated that offseason.

The QB was Drew Bledsoe, the No. 1 overall pick in the 1993 draft who guided New England as far as that Super Bowl defeat against Green Bay. Twice a 4,000-yard passer, and now 29, Bledsoe's play had slipped in concert with the Pats' slide down the standings over the past couple of seasons, bottoming with a distant last-place finish in the AFC East in 2000. Still, it didn't seem likely that any of his backups would supplant him: not the veteran John Friesz, soon to retire; not the youngster Michael Bishop, soon to be out of the league; and not fourth-stringer Tom Brady, who attempted three passes as a rookie.

Brady, for what it's worth, was held in high regard by Dick Rehbein, the Patriots QB coach who died of heart failure at age 45 during the first week of the 2001 preseason. More than a year before Rehbein's sudden passing, he'd seen something in Brady during scouting visits to the University of Michigan - maybe his competitiveness, maybe his aptitude in the clutch - that reminded him of Brett Favre and Joe Montana. Rehbein encouraged Belichick to select the spindly, slow-footed prospect late in the 2000 draft.

"Twenty years from now," Rehbein said at the time to his wife, Pam, as recounted in a 2015 ESPN story, "people will know the name Tom Brady."

Twenty years remained far off early in September 2001, when SI's NFL preview issue declared St. Louis Rams running back Marshall Faulk the best player in football, made no mention of Brady, and picked the Patriots to repeat as AFC East cellar dwellers. "If Drew Bledsoe ever needed to play like a $103 million man, it's now," the magazine wrote, evidently doubting that the 22 free agents New England signed - among them running back Antowain Smith, wide receiver David Patten, and linebackers Bryan Cox, Roman Phifer, and Mike Vrabel - would make much difference.

After the Patriots lost to the lowly Bengals on Sept. 9, their Week 2 home opener against the Jets produced the season's first indelible moments. One resonated beyond football. Following the 9/11 attacks, the NFL paused play for a week and then returned on Sunday, Sept. 23 with nationwide tributes to the victims and emergency rescuers. In Foxborough, Pats guard Joe Andruzzi was introduced carrying two American flags, and his three brothers, each a New York City firefighter who served at Ground Zero, were honored ahead of kickoff at midfield.

New England lost the game 10-3 - and lost Bledsoe to injury in the oft-cited, inadvertent turning point in franchise history. Trailing by that score late in the fourth quarter, Bledsoe hustled to the right sideline on a third-down rollout, decided against ducking out of bounds for safety, and was crunched by oncoming linebacker Mo Lewis.

"It was the loudest hit I could ever remember hearing," Brady told the late journalist Don Banks for a 2016 NFL.com story. "Drew was so tough, and he got up and came to the sideline and his face mask was smashed."

The blow concussed Bledsoe and sheared a blood vessel in his chest, causing internal bleeding, but that damage was identified only after he returned for the next series. Bledsoe executed two handoffs and completed a short pass that was fumbled away before he left the field and, eventually, was rushed to hospital.

In the meantime, the Patriots became Brady's team, starting with the second drive of the 24-year-old backup's career. Pressed into action with 2:16 left, Brady marched New England 55 yards in seven plays, but failed to connect on two last-gasp heaves to the end zone.

If the significance of the substitution wasn't immediately apparent - Bledsoe was expected to miss some time and then resume starting - that was only true for a few more weeks. Brady showed himself to be a competent new No. 1 option; sometimes, he looked magnificent. In Weeks 3 and 6, he was efficient as New England blew out a soon-to-be familiar foe, the Colts and their All-Pro QB Peyton Manning. (This was the disappointing Indy season of Jim Mora's "Playoffs!?" fame.) In Week 5, Brady shredded the Chargers for 364 yards and two TDs, including one in the final minute of regulation that set up an overtime victory.

The Pats were 5-4, and 5-2 with Brady starting, when the Rams arrived in Foxborough for a Sunday Night Football matchup on Nov. 18. Doctors had just cleared Bledsoe to return at a seemingly opportune time: New England had to try to keep pace with "The Greatest Show on Turf," the Faulk- and Kurt Warner-led offense that helped St. Louis surpass 500 points scored in three straight seasons.

How's this for evidence of a sea change: the news barely registered. As Hartford Courant reporter Alan Greenberg wrote ahead of the game, "At this juncture, it could be argued, Bledsoe needs the Patriots more than they need him."

In the end, St. Louis won 24-17 on ESPN, but despite Warner throwing for 401 yards and three TDs, New England's defense forced three turnovers and made an impression on the NFC side, the Super Bowl champs in 1999. As Bledsoe relayed to the Boston Herald in 2016, Rams coach Mike Martz sought out Belichick postgame to say something to the effect that the teams would probably face off again.

“Which meant the Super Bowl," Bledsoe said, "because that’s the only other way we could have played them."

Belichick's charges not only proved Martz prescient, but did so emphatically. Nine games remained for the 2001 Pats to play, including six before the playoffs, and New England won all nine.

Of the Pats' laurels from their 11-5 regular season - the AFC East title; Pro Bowl nods for Brady, receiver Troy Brown, cornerback Ty Law, and safety Lawyer Milloy - none were more important than the No. 2 seed in the conference, which granted them a first-round playoff bye and home field for a divisional round game held in a blizzard.

This was the Jan. 19, 2002 matchup that New England fans remember as the Snow Bowl, and that Raider Nation still bemoans for referee Walt Coleman's enforcement of the Tuck Rule. A primer for the uninitiated: after an arduous first three quarters that featured 13 punts, and after a fourth-quarter drive on which Brady hit nine consecutive passes and ran for a touchdown, Brady dropped back to pass with 1:50 to go and the Patriots trailing 13-10. He pumped the ball and was rocked by blitzing defensive back Charles Woodson, forcing a fumble that would have ended the game.

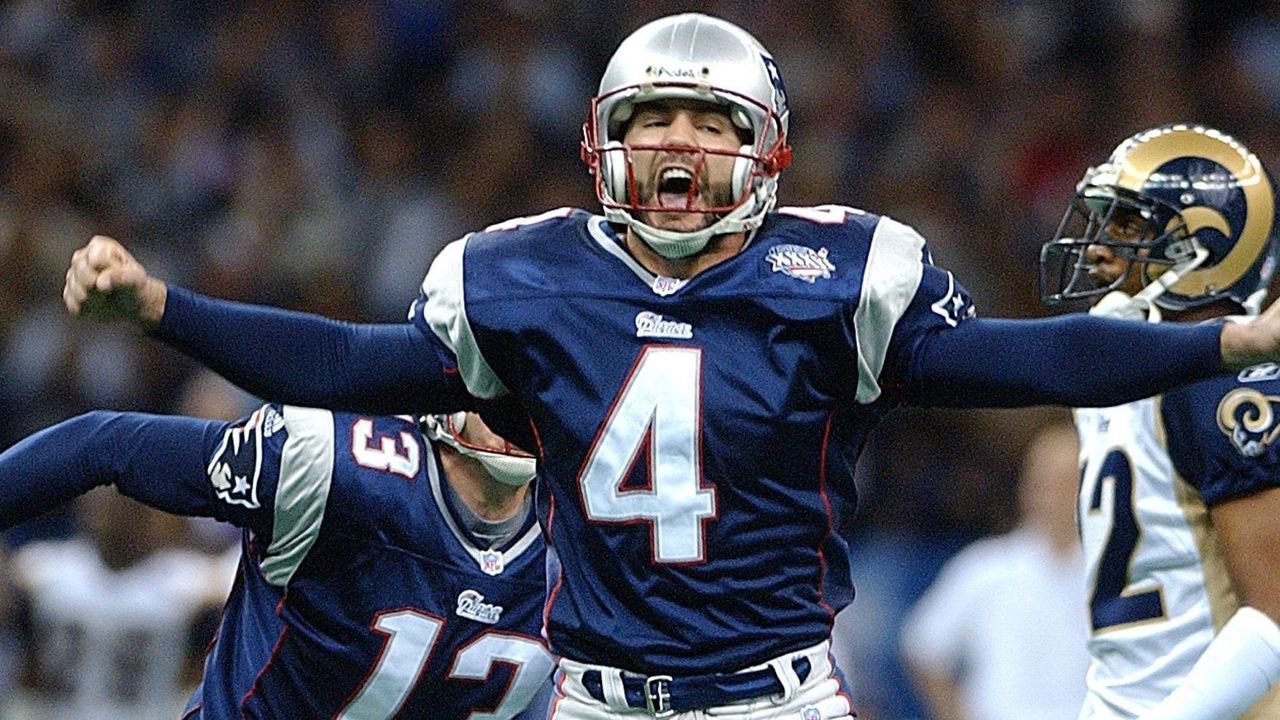

In the 32nd year of their NFL existence, maybe the Patriots were due a little luck. What happened next is the stuff of legend: Coleman, upon review, overturned the call by ruling that Brady's arm motion made the play an incomplete pass; Pats kicker Adam Vinatieri subsequently nailed a 45-yard field goal through the storm; Brady completed eight straight passes on the first drive of OT, the last a 6-yard gain on fourth-and-4 in Raiders territory; Vinatieri, several plays later, booted a simpler 23-yard FG to send New England to the AFC championship.

That game contained its own unforgettable storyline: the revival of New England's $103-million man. At Heinz Field on Jan. 27, with the Patriots leading the top-seeded Steelers 7-3 in the second quarter, safety Lee Flowers buckled Brady's legs on a blitz, spraining Brady's left ankle. In came Bledsoe for his first action since Week 2; he hurled a TD pass to Patten and, after halftime, watched from the sideline as the Pats' Antwan Harris scored on a blocked-FG return. Two late interceptions quelled Pittsburgh's comeback attempt, and New England won 24-17.

The next passes Bledsoe threw were for the Bills, the division rival to which the Patriots traded him that April in exchange for a first-round pick. To Belichick, the dilemma before him heading into the Super Bowl - stick with the nine-figure backup or trust the nerve of his fledgling replacement - hardly constituted a controversy. "Tom Brady demonstrated in practice today that he is fit to play," the coach said, with characteristic concision, in a statement the Pats issued the Wednesday night before the game. "He will be our starting quarterback on Sunday."

Today, Super Bowl XXXVI in New Orleans is the Pats' ninth-most recent championship appearance - and, remarkably, the last that their opponent was favored to win. The Vegas line, Rams -14, suited a 14-2 NFC champ that didn't trail by double digits all season, and whose leading stars, Warner and Faulk, finished first and second in MVP voting, respectively.

What followed was a transformative upset that ended one potential dynasty and launched another. The Pats hadn't allowed 20 points in any game since their midseason loss to the Rams. On Feb. 3 at the Superdome - coincidentally the site of New England's previous Super Bowl defeats - the defense intercepted Warner twice (once for a pick-6) and generally pounded his playmakers for three quarters. However, the Rams' Greatest Show on Turf found its form in the fourth and erased a 17-3 deficit with two clinical TD drives.

The Patriots' game-winning final drive typified New England's season - who could have seen it coming? - and established Brady as a folk hero. With 1:21 on the clock, no timeouts, and the ball on the Pats' 17, Belichick dispatched his QB with instructions to score, not to kneel and reset for overtime.

"With a quarterback like Brady, going for the win is not that dangerous," Belichick said postgame, explaining his rationale via the same publication that had figured New England would finish last in the division. "He's not going to make a mistake."

Smart thinking. Dick Rehbein's protege's passes were on point: a 5-yard completion to running back J.R. Redmond; eight yards and then 11 more to Redmond again. From his 41, Brady hit an open Brown for 23 yards and he was able to scamper out of bounds. Soon New England was in field-goal range, and soon Vinatieri's offering from 48 yards was true, sparking elation as time expired and effectively ensuring that every Patriots letdown that preceded the moment wouldn't be remembered much longer.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- Report: Raiders expected to promote Leonard to defensive coordinator

- Report: Jags plan to utilize Hunter as full-time CB, part-time WR in 2026

- NFL wins grievance against players' union, banning 'team report cards'

- Patriots' Diggs pleads not guilty to charges in alleged assault

- Carr: I'd only unretire for a Super Bowl contender