The backup QB who proved to be more than a second banana

After "The Last Dance" reminded fans of the greatness of Scottie Pippen existing in the shadow of Michael Jordan, theScore's feature writers decided to examine some of the most compelling second bananas in other sports. Previous entries in the series came from college football, MLB, and NHL.

Earl Morrall was a kind of football everyman. But that pithy description doesn't come close to doing him justice. He basically packed multiple careers into his 21 seasons with six different teams. He was the best backup quarterback in NFL history, his path constantly pocked with both failure and success.

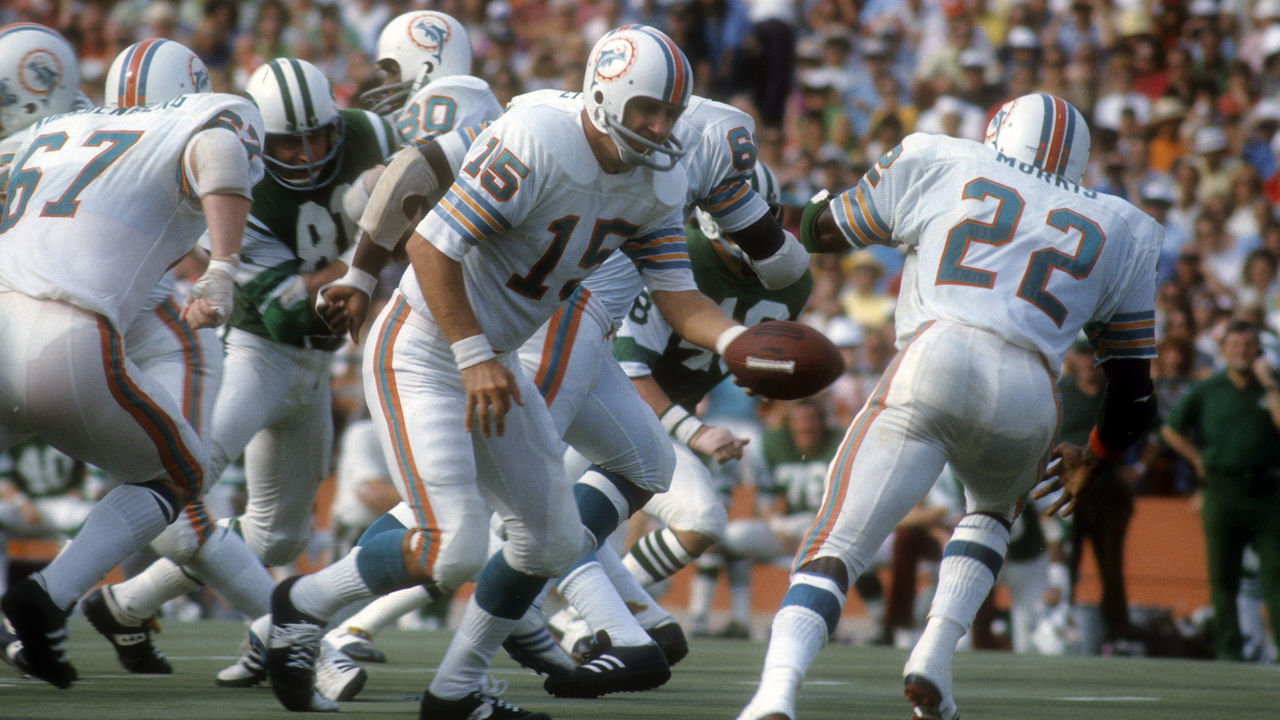

Morrall died in 2014 at 79. He's most famous for his stints with the Baltimore Colts and Miami Dolphins, for whom he zigged as a backup and zagged as a starter - with decidedly different outcomes under markedly different circumstances. He reached the Super Bowl with the Colts and Dolphins four times, winning three. But he did all that by playing four distinct roles as a stand-in for future Hall of Famers Johnny Unitas and Bob Griese - after he'd reached the age of 34. He also did all that after he spent a dozen seasons as the textbook definition of a journeyman.

The list of QBs to begin a season as a backup before taking over to win the Super Bowl is longer than one might think. It includes Jim Plunkett, Doug Williams, Jeff Hostetler, Kurt Warner, Trent Dilfer, Tom Brady, and Nick Foles. It's a footnote now, but even Roger Staubauch and Terry Bradshaw first won Super Bowls in seasons they began on the bench. But compared to all the others, Morrall's career was supremely unique.

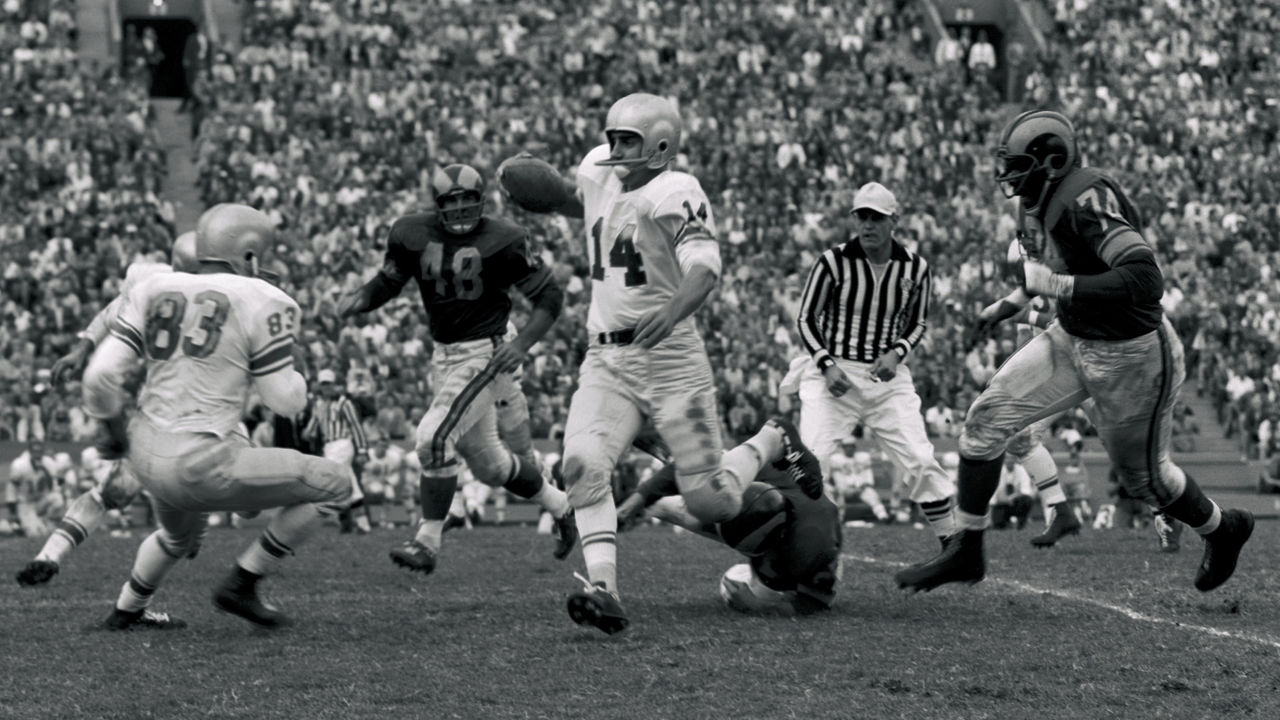

Before his golden years with the Colts and Dolphins, Morrall clocked in with the San Francisco 49ers, Pittsburgh Steelers, Detroit Lions, and New York Giants. He always seemed to be good enough - but only to a point. All told, Morrall made 102 starts out of 255 regular-season games played; he posted a .632 winning percentage in those starts. He also won four of the five playoff games he started.

Yet that barely begins to tell the story. Morrall lost a Super Bowl as a starter, won one as a replacement, and served as a backup in two others, one of which involved a season in which he went 10-0 for the only NFL team to ever go undefeated, only to wind up back on the bench anyway. To this day, Earl Morrall's career stands as a testament to the value NFL teams continue to place on the quarterback as a position.

"He was always in the right place at the right time to come in and relieve (other) guys," Morrall's son Matthew told me. "But as far as starting as a long-term player, he was not ever given that opportunity. Everywhere he went, he played with a Hall of Fame quarterback."

Indeed, Morrall teamed with a Hall of Famer at five of his six NFL stops. He had pedigree, but his NFL journey up to the age of 34 always seemed to be jagged by circumstance. Let's quickly run through it.

49ers: After winning the Rose Bowl at Michigan State, Morrall was selected No. 2 overall in the 1956 draft by the Niners. He largely played behind Y.A. Tittle for a year before the Niners took John Brodie with the No. 3 pick a year later.

Steelers: After passing on Morrall with the top pick in 1956, the Steelers attempted to chase that mistake by trading for him. Pittsburgh did this even though it also took future Hall of Famer Len Dawson with the No. 5 overall pick in 1957, and even though it also had future AFL star (and eventual politico) Jack Kemp on the roster. None of this appeared to be rooted in any grand plan to backstop the QB position with depth - the Steelers just didn't know what the hell they were doing. They also drafted Unitas in 1955, only to cut him before he played a down. Pittsburgh is now considered a blue blood NFL franchise, but before the 1970s, its general operating principle was to consistently pie itself in the face.

Lions: Morrall made the Pro Bowl as the Steelers' starter in 1957, but he was traded to the Lions two games into the 1958 season because Pittsburgh head coach Buddy Parker wanted to reunite with Bobby Layne, whom Parker coached in Detroit. Morrall spent seven seasons with the Lions, where he was often part of a rotation that variously included Tobin Rote, Jim Ninowski, and Milt Plum. Even then, the Lions had a way of being the Lions: At one point before a game, head coach George Wilson couldn't bring himself to choose a starter, so he flipped a coin. Morrall lost. In 1965, the Lions traded Morrall to the Giants, where he replaced the recently retired Tittle.

Giants: Morrall went 7-7 in his first season with the Giants, a year after they went 2-10-2. He then struggled in 1966 before a broken wrist ended his season. To jump-start things, the Giants traded for future Hall of Famer Fran Tarkenton, which relegated Morrall back to the bench, where it looked like he'd remain. "At 34 years of age and with a 30-33-2 career record, Morrall appeared finished," Football Perspective's Chase Stuart once wrote. "But with Morrall, things were never as they appeared."

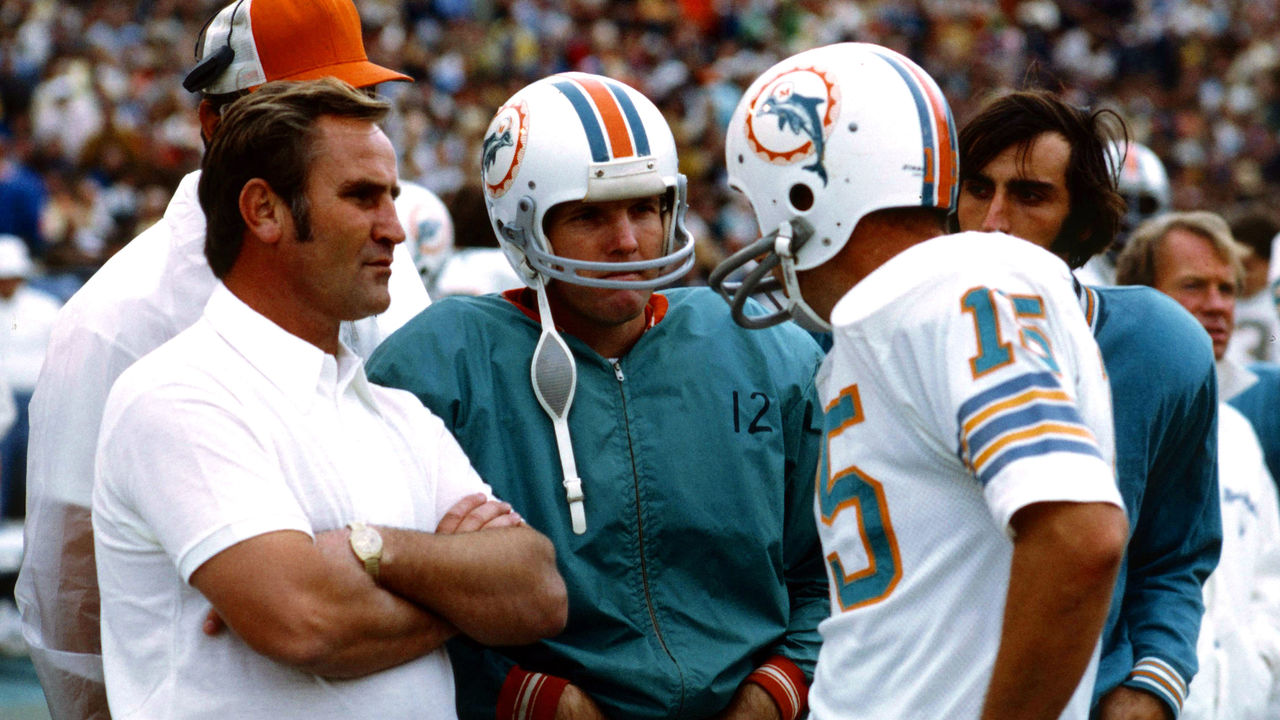

In August 1968, with Unitas battling some elbow troubles, Colts head coach Don Shula traded for Morrall. Shula, who died on May 4 and is still the winningest coach in NFL history, knew Morrall. His three seasons as a Lions defensive coach from 1960-62 overlapped with Morrall's tenure. The two men were only four years apart in age, and Shula felt Morrall could be a stable backup. The move proved to be prescient after Unitas felt a pop in his elbow during the Colts' final preseason game.

Finally getting his chance with a championship-caliber team, Morrall threw for 2,909 yards and 26 touchdowns - big numbers for the NFL in 1968 - and was named league MVP. It remains one of the greatest age-34 seasons for a QB in pro football history. The Colts finished 13-1 and avenged their only loss with a 34-0 destruction of the Cleveland Browns in the NFL Championship Game. They entered Super Bowl III against the New York Jets as 18-point favorites.

Joe Namath, the brash Jets QB, publicly and famously guaranteed a victory over the Colts. But he also dissed Morrall more than once, first by insisting just after the AFL title game that Raiders QB Daryle Lamonica - whom the Jets had just beaten - was better than Morrall. Then, when asked about those remarks by Dave Anderson of The New York Times just before the Jets flew to Miami for the Super Bowl, Namath suggested his own backup, Babe Parilli, was better, too.

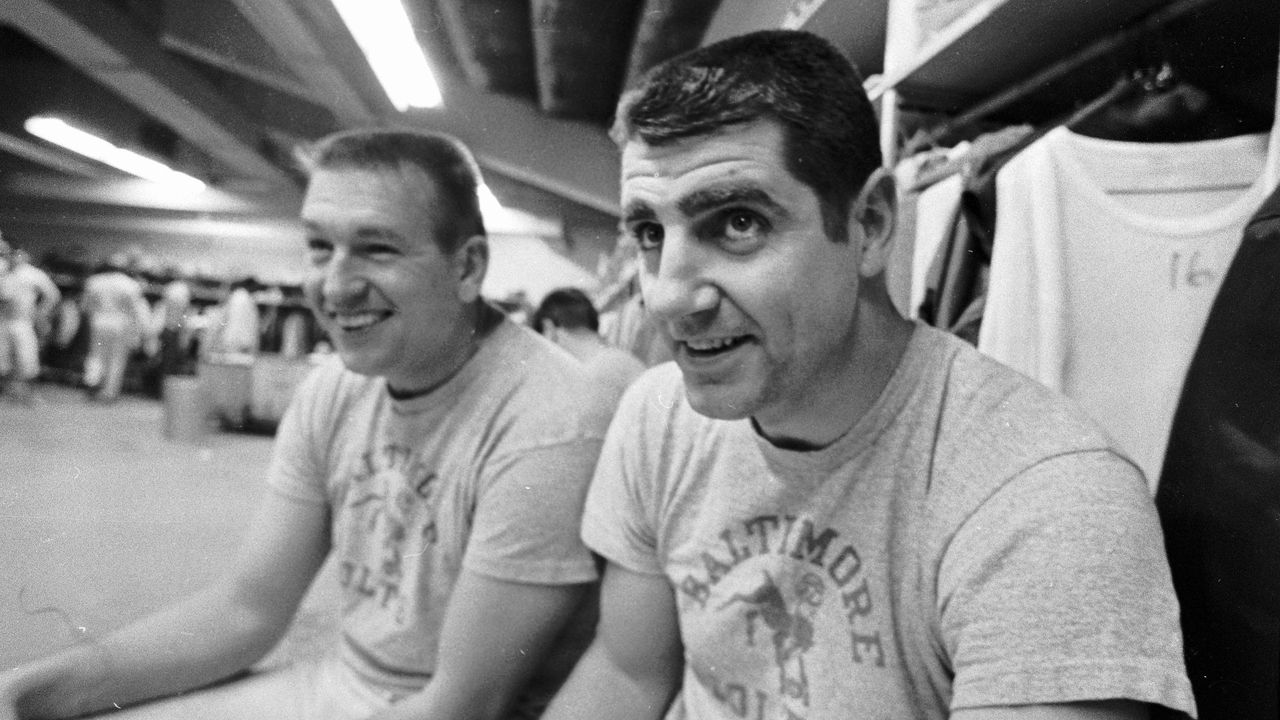

There was a broader significance to Super Bowl III that mirrored the culture at large. The crew-cutted Morrall and Unitas represented the NFL's old guard and the quiet rectitude the league liked to project, while the sideburned Namath - who made no effort to disguise his taste for booze, women, and colorful talk - stood for the wide-open, freewheeling AFL. The two leagues were slated to soon merge, but the AFL was still trying to prove it belonged. Super Bowl III would settle the matter once and for all.

Morrall famously struggled in Super Bowl III, completing just 6 of 17 passes and throwing three interceptions before being benched for Unitas in the second half. On one of Morrall's picks, he never saw a wide open Jimmy Orr streaking up the left sideline toward the end zone, frantically waving his arms. Baltimore's 16-7 loss remains one of the biggest upsets in league history, and it hastened Shula's eventual departure for Miami after the 1969 season. But Shula wouldn't forget about Morrall - and Morrall wouldn't forget about Namath.

A few years later, when Morrall was with the Dolphins, he let down his guard, though he would later claim he didn't know he was talking to a sportswriter. According to Mark Kriegel's 2004 book, "Namath: A Biography," in a moment of what Kriegel described as "uncharacteristic candor," this is what Morrall had to say about Namath:

I don't respect him. His lifestyle, his actions. I wouldn't want to follow in his footsteps. I don't want to be like him and I hope my kids and the younger generation don't grow up to be like him. I don't think that's the style, for everybody to be big talkers, to be high-livers, and to be out chasing.

When Namath and Morrall met on the field a few days after those words were published, Namath refused to shake Morrall's hand during the pregame coin toss. "Morrall only chuckled," according to Kriegel. "This wasn't his revenge, but it was as close as he would get. Morrall, thirty-nine years old, ran for a thirty-one yard touchdown that day." The Dolphins won.

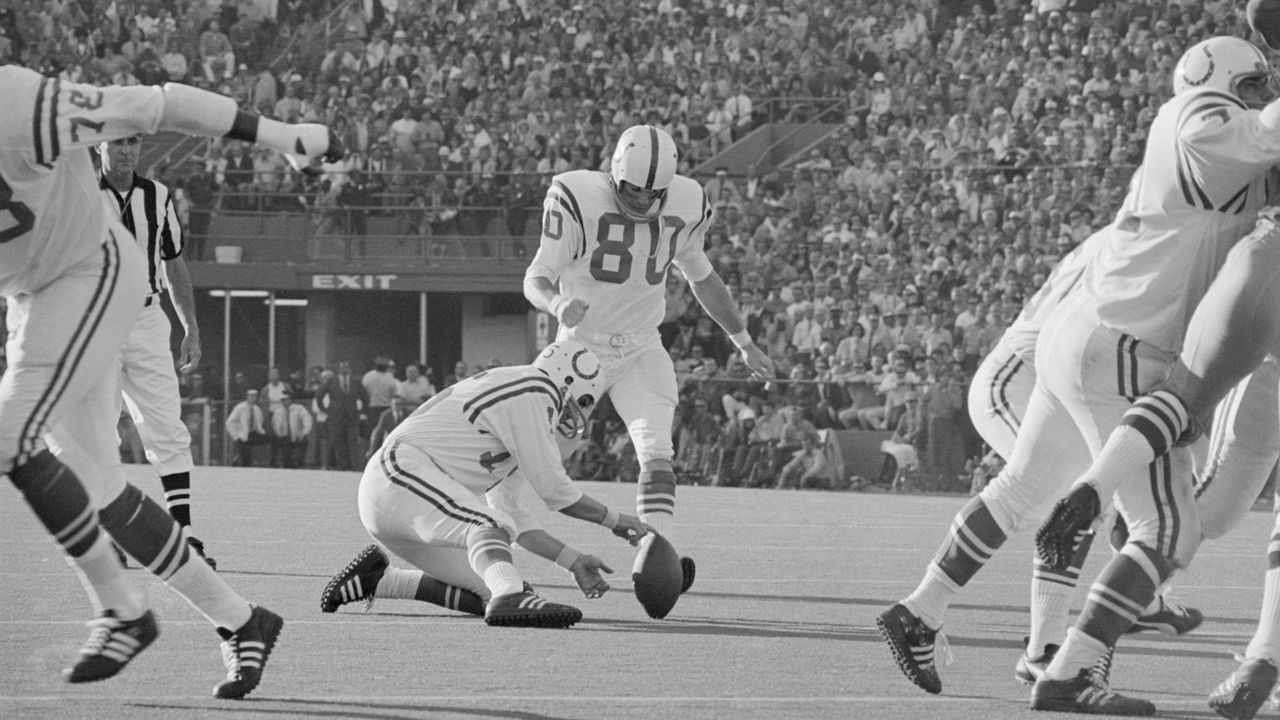

Morrall made just three starts for the Colts in 1969 and 1970, but he'd get another crack at a Super Bowl two years after that heartbreaker against the Jets - this time by replacing Unitas. In the second quarter of Super Bowl V against the Dallas Cowboys, Unitas was knocked out of the game with the Colts trailing 13-6. Morrall came on in relief and completed 7 of 15 passes for 147 yards. A pair of interceptions deep in Dallas territory led directly to the 10 points Baltimore needed to win it. Morrall was a Super Bowl champion, and he had a direct hand in making it happen that went beyond being the holder on kicker Jim O'Brien's game-winning field goal with nine seconds remaining.

Morrall and Unitas split time for most of the 1971 season, with Morrall starting the first nine games before Unitas got the keys the rest of the way. The Colts' season ended with a loss to Shula and the Dolphins in the AFC Championship Game. Morrall, who was about to turn 38, was waived the following April, and Shula sought him out again - this time to back up Griese, who guided the Dolphins to the Super Bowl a year earlier. There was one catch.

Shula had to convince Dolphins owner Joe Robbie to agree to pay Morrall $90,000 - a salary the South Florida Sun-Sentinel later reported was higher than what was to be earned by all but one other Dolphins player.

"That just tells you the conviction my dad had for what Earl brought to the team," Shula's son David told me.

The move was ahead of its time: Such acute resource allocation is today an organizational philosophy for quantitative-minded teams like the Philadelphia Eagles, who just used a second-round pick on Jalen Hurts even though they're financially committed to Carson Wentz as the starter.

Shula in 1972 obviously wasn't crunching any numbers to understand the value of the QB position beyond the starter. But David Shula said his father had learned from experience. In 1965 with the Colts, Shula was reduced to starting running back Tom Matte at QB in a playoff game. Three years later, of course, Morrall had his MVP season in relief of Unitas.

"He knew that you needed to have a quality backup, for sure," David Shula said of his father. "Lo and behold, he ends up being the guy."

Yep. In 1972, that investment would prove to be worthwhile. Griese injured his leg and ankle in Week 5, but Morrall took the reins and guided the Dolphins to a 14-0 regular-season finish and a playoff win. He was also named first-team All-Pro. But Griese eventually returned to health, and after Morrall struggled a bit against the Steelers in the AFC Championship Game, Shula elected to play Griese in the second half. The Dolphins won, and Shula chose to stick with Griese for Super Bowl VII, later saying, "It probably was the toughest decision I've ever had to make." Miami would go on to beat Washington 14-7 to cap a perfect season.

"Picture the public debate today about who should be the starter," David Shula said. "But when I think about Earl Morrall, I think about his dignity, his grace. I never saw - and I was around him a lot, from being around his kids - him say anything negative at all about what had happened. He was just so happy to be a part of an undefeated team, and he was that way for the rest of his life."

Morrall's son Matthew acknowledged his father was a competitor who was "frustrated" by so often having to be a second banana, especially in Super Bowl VII. But deep down, Matthew Morrall said, his father saw that was part of the job he was asked to do.

"He always believed in himself, but his frustration never showed during his time of playing, and for many years afterwards," Matthew Morrall said. "He never said, 'I should have played in the Super Bowl.' He told Coach Shula at the time during the perfect season, 'I disagree with your decision, but I'm going to support you.' And Coach Shula basically said, 'Earl, you're very capable of coming off the bench, you've done that for many years, and that's something that we can use, if necessary.'"

Earl Morrall played sparingly as Griese's backup as Miami repeated as Super Bowl champions in 1973. He stayed on with the Dolphins through the 1976 season, when he retired at the age of 42. In his seven seasons playing for Don Shula, playoffs included, Morrall went 29-3-1 as a starter.

After retirement, Morrall became the quarterbacks coach at the University of Miami, where we worked with Jim Kelly, Bernie Kosar, and Vinny Testaverde. He later served on the city council and became mayor of Davie, Florida, before making an unsuccessful run for the Florida House of Representatives. In his later years, Morrall suffered from a variety of ailments including Parkinson's disease. A posthumous examination of his brain revealed he had Stage 4 CTE, confirmation of a long decline Matthew once described to the Palm Beach Post as "horrific."

I asked Matthew Morrall if he felt his father has been appreciated for his football career.

"Of all of his teammates and all of the people that knew him throughout his career - opponents, teammates, everybody - I don't know that I've ever heard anyone other than Joe Namath say anything bad about my dad," Matthew Morrall said. "Even today, when I meet people that he played with that I did not know that well, they'd tell me what a tremendous pleasure it was to have played with my father."

Not a bad legacy for a backup quarterback.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.