So many traps await NFL teams trying to find a star QB in the draft

During this week's NFL draft, the first 10 selections could include as many as five quarterbacks. Such an early run on QBs would be unprecedented, even for a league that places so much outsized value on the position. Yet for all the attention the top draft-eligible quarterbacks annually receive, the likelihood is that most will not pan out.

A recent ESPN report found that of the 45 signal-callers taken in the first round between 2000 and 2016, just 19 (42.2%) landed second contracts with the team that selected them. Not one of the 22 first-round QBs chosen between 2009 and 2016 is still with the team that picked him. And you're probably aware that the greatest quarterback of all time - some dude named Tom Brady, who just won his seventh Super Bowl at the tender young age of 43 - was selected in the sixth round, with the 199th pick, behind six other quarterbacks.

The draft is largely a crapshoot as a whole. A boatload of deep dives over the years has shown that NFL teams - all of them - are generally bad at picking players, regardless of position. This cold reality stands in stark contrast to the popularity of the draft industrial complex, that annual season of hype and anticipation that exists to offer fans the constant illusion of hope. Your team is absolutely going to be fixed by this year's draft crop, I swear. Unless your team totally screwed things up, which is also entirely possible, too, I guess. Who knows!

Anyway, let's turn our focus toward drafting a quarterback, because the quarterback is at once the game's most important position and its most inscrutable.

Overconfidence

Quality quarterbacks are scarce. It's what sets them apart, and it's the reason they're so expensive, with the top of the veteran contract market averaging nearly $20 million more in annual value than any other position.

Yes, teams have won Super Bowls with an OK QB surrounded by a solid supporting cast: Nick Foles, Joe Flacco, Brad Johnson, Trent Dilfer, to name four from the last 20 years. But the surest path to sustained success, to consistently remaining in the chase for a championship, where the difference between winning and losing can be painfully small, is to have a great QB.

Take what 49ers head coach Kyle Shanahan said last month after San Francisco traded away two future first-round picks plus a third-rounder to move up from No. 12 to No. 3 in this year's draft: "There's a risk any season you go into without a top-five QB."

Seems pretty simple, right? Yet despite the hype that engulfs the run-up to every draft, the process of identifying a great QB is far more complex than just drafting the best one on the board in a given year. For every sure thing like John Elway, Peyton Manning, Andrew Luck, and now (maybe?) Trevor Lawrence, there are great ones like Patrick Mahomes, Russell Wilson, Aaron Rodgers, Drew Brees, and Brady who were selected outside the top five or even in the third round or later.

One reason is overconfidence on the part of scouts, personnel executives, front offices, and owners. It's a phenomenon that was first detailed empirically in a seminal 2005 academic study of the entire draft that was co-authored by University of Pennsylvania professor Cade Massey and University of Chicago professor Richard H. Thaler (emphasis mine):

Our modest claim in this paper is that the owners and managers of National Football League teams are also human, and that market forces have not been strong enough to overcome these human failings. The task of picking players, as we have described here, is an extremely difficult one, much more difficult than the tasks psychologists typically pose to their subjects. Teams must first make predictions about the future performance of (frequently) immature young men. Then they must make judgments about their own abilities: how much confidence should the team have in its forecasting skills? As we detailed in section 2, human nature conspires to make it extremely difficult to avoid overconfidence in this task. The more information teams acquire about players, the more overconfident they will feel about their ability to make fine distinctions.

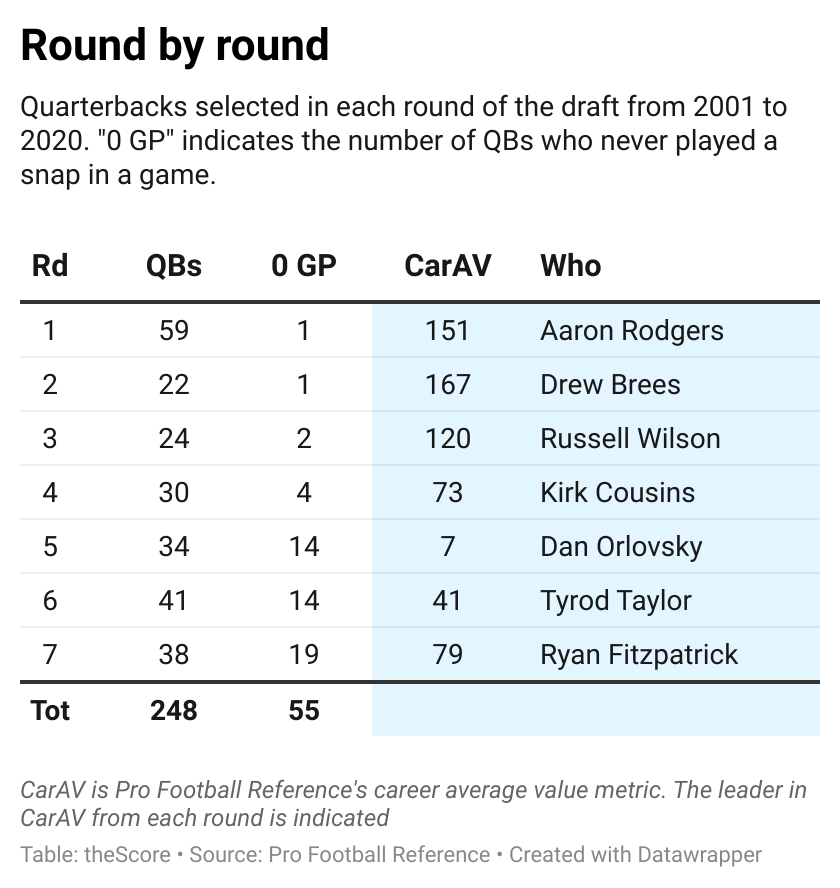

Interestingly, a self-assurance that's specific to drafting quarterbacks has only increased since the publication of that paper. Peter King of NBC Sports recently noted that the average draft slot of the first QB selected between 1980 and 2000 was 13.9. But from 2001 to 2020, that number was 2.1. And while a QB was taken No. 1 overall just seven times between 1980 and 2000, that number jumped to 15 in the last 20 drafts. In the last six drafts alone, 15 quarterbacks were chosen in the top 10.

A lot of quarterbacks have been chosen in the later rounds, too, though most of them haven't been good. Starting with 2001 - the year after Brady was selected in the sixth round - 142 quarterbacks have been selected with pick No. 101 or later. Of that group, Kirk Cousins, Ryan Fitzpatrick, Dak Prescott, and Tyrod Taylor have had some staying power. But more than a third - 51 in all - never even appeared in an NFL game, let alone started one.

Why do teams keep drafting quarterbacks when so many don't succeed? It seems a lot of teams follow the philosophy of former Green Bay Packers general manager Ron Wolf, who believed in drafting a QB as often as possible to maximize the chances of grabbing a good one. Even the New England Patriots, who spent 20 years owning the rest of the league, spent 10 draft picks on quarterbacks during that time despite having Brady on the roster.

Additionally, the rookie wage scale that went into effect with the 2011 collective bargaining agreement made drafting quarterbacks more cost-effective. Arizona might have made a mistake by drafting Josh Rosen No. 10 overall, but it could financially afford to move on and select Kyler Murray No. 1 overall a year later. Also, there's now a lot of turnover for coaches and general managers, which puts more pressure than ever on teams to win right away, which sometimes leads them to overdraft by reaching for a quarterback.

"I think it's just been a total shift over the last couple years, and I don't think it's going away," NFL Network analyst Daniel Jeremiah said on a recent conference call with reporters. "That's why, to me, I think we identify who the teams are that are in the quarterback market, but when you really look at it and you say, well, if you think you can just get this much better, then there might be more teams in the quarterback market than we all know."

Coaching

The same hubris that Massey and Thaler identified also frequently applies to coaches, as Pro Football Network draft analyst Tony Pauline told me.

"Teams and scouts look at things as to what a player does well - what can he do?" Pauline said. "And sometimes they'll stay away from what things a guy doesn't do well, because they're football coaches. They see a guy that's 6-2½, 6-3, 6-3½, 220, 225 pounds, he's athletic, but he can't hit the broad side of a barn. They'll say, 'I'll teach this kid to be accurate,' or 'I'll show him how to read defenses.' And it's like trying to teach me to speak Chinese - it's never going to happen."

The quarterback position is further complicated by the stylistic differences of the high school and college games, where quick-read spread systems increasingly became the norm during the 21st century. Yet even as pass-heavy approaches and three-receiver formations came to dominate NFL offenses well into the 2010s, there remained a stubborn insistence that quarterbacks had to be traditional pocket-style passers. This resulted in a quarterback crisis that explains a fair number of the first-round flameouts between 2009 and 2016. Then smart coaches began tailoring their schemes around what their young QBs do best.

Mahomes, drafted 10th overall in 2017 after the Chiefs traded up to nab him, is the perfect example. Most draft experts at the time ranked Mahomes behind Mitchell Trubisky and Deshaun Watson in a class NFL.com once headlined as "lacking elite talent." Dane Brugler, another draft analyst now with The Athletic, even ranked Mahomes behind Trubisky, Watson, and DeShone Kizer. Brugler told Cleveland.com that Mahomes was "a complete projection because he's playing backyard football out there. Not much structure. It's easy to say, 'Well, give him a year or two in development and you'll have something.' Except that a lot of it's muscle memory. He's used to playing quarterback his way. It's not easy to take him out of what he's always done and turn him into something else."

This is not to pick on Brugler, who also said in that same interview that Mahomes "has the arm talent, the size, the mobility that you want." Rather, it's to demonstrate how much coaching and circumstances can shape a quarterback's trajectory. Jordan Palmer, a former quarterback who now works as a private throwing coach for a number of NFL QBs and college prospects, elaborated on this during a recent panel discussion at MIT's Sloan Sports Analytics Conference.

"I don't think Mahomes would have had the same success anywhere," Palmer said, before launching into a story about a conversation he had a few years ago with Cardinals head coach Kliff Kingsbury, who coached Mahomes at Texas Tech.

“Kliff said he went to the perfect spot because Andy Reid’s one of the only people who had the confidence to say, 'I'm not going to change you,'" Palmer added. "It took humility from Reid to not try and change him, and I could build a long list of coaches who would have tried to change Patrick."

Palmer's take isn't new or unique, either. In "The Blind Side," Michael Lewis' 2006 book about the evolution of offensive football, the innovative head coach Bill Walsh had this to say about the penchant of a quarterback to succeed or fail:

The performance of a quarterback must be manipulated. To a degree coaching can make a quarterback, and it certainly is the most important factor for his success. The design of a team's offense is the key to a quarterback's performance. One has to be tuned to the other.

Ryan Tannehill's improved performance with the Titans is another excellent demonstration of Walsh's hypothesis. The Colts' acquisition of Carson Wentz and the Panthers' trade for Sam Darnold were also done with Walsh's line of thinking in mind. The point is that if Wentz and Darnold are unable to produce at their next stops, they'll both be out of excuses.

What it takes

There are a number of traits most commonly associated with successful quarterbacks. Accuracy is one of them. Arm strength is another. For a long time, size was considered a factor, though the successes of Brees and Wilson upended that paradigm, with Baker Mayfield, Murray, and Tua Tagovailoa now serving as their natural (smaller) successors.

The application of quantitative analysis and player-tracking data has helped teams (and fans) gain a better understanding of characteristics like accuracy and situational performance. Advanced metrics like expected points added (EPA), completion percentage over expected (CPOE), and air yards versus yards after the catch can provide a much better gauge than traditional volume stats and archaic benchmarks like passer rating.

“Our understanding of what makes a quarterback good versus bad has come a long way," former Browns director of research and strategy Kevin Meers said at Sloan. “So we’re able to get smarter statistics from these different data sources.”

But beyond these attributes and what can be quantified - and beyond what coaches can do to "manipulate" a QB's performance, as Walsh put it - there is something deeper. Quarterback play is also about two distinct qualities that are often too abstract for teams to suss out: confidence and decision-making.

"There's two types of confidence," Palmer said at Sloan. "There's reactionary confidence and there's self-generating confidence. And reactionary confidence is dangerous. It's dependent on the environment: If everybody says you’re good, you believe them. If everybody says you're a bum, you wonder if they're right. Self-generating confidence is completely independent of the environment: 'I don't care what you think. This is what I believe about myself.'

"If you don't have self-generating confidence or if you have reactionary confidence, (that's) a bigger red flag than anything else."

Decision-making is also tricky to pin down, though the math folks are working on it. At the 2019 Sloan conference, ESPN's Brian Burke presented a paper that used player-tracking data from the 2016 and 2017 seasons "to assess and compare individual quarterback pass target selection based on a snapshot presented to the passer by the receivers and defenders." Burke also used video analysis to decipher whether a QB was under pressure or used play-action. Armed with all that data, he developed a neural network that was designed to predict who a QB should be targeting.

"Over time, (the neural network) learned the patterns,” Burke told The Ringer's Robert Mays last year. "(I could) tell it the X and Y position of all the receivers and all the defenders and a whole bunch of other information, and it would learn the pattern. It would learn, 'Oh, this player's wide open.' Or, 'This player's not wide open, but he has a step on his defender.' Or, 'Oh, there’s no safety in the middle of the field. So he's probably going to throw the post.' Over time it learned to predict with pretty good accuracy which receiver would be thrown to."

But Palmer, who's come to embrace analytics in his QB development program, isn't as bullish - at least not yet - on the application of machine learning to QB decision-making because coaches and teams are constantly tweaking commonly understood play concepts.

"The hard one for me on decision-making is going to be that a lot of times (watching tape can be misleading). And, by the way, I watch people on tape, and I look at a concept that I recognize, that I go, 'Oh, this is the concept. Why is he throwing it here? This guy should be No. 1 in that progression,'" Palmer said at Sloan. "But what I don't know is whether they talked about that play differently that week. And that happens all the time."

As more data becomes available, however, more will be possible.

"You need to understand how the play is designed and where the quarterback is supposed to be going with the ball," Meers said at Sloan. "But if the analytics movement can start to build metrics that understand those intricacies, then we can really go a long way to understanding not just which quarterback is accurate and which one creates for value for his team, but which ones are making good decisions with the football and which ones aren't."

In the meantime, teams will keep taking quarterbacks, and they and their fans will keep hoping for the best.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.