Why players must keep reminding the NFL what 'voluntary' means

The NFL Players Association had the right idea when it encouraged players to skip this offseason's organized team activities. These workouts, after all, are voluntary - a word with a specific meaning that long ago was bargained into the NFLPA's collective bargaining agreement with the league.

What the players didn't count on was the NFL's willingness to weaponize a good-faith loophole in that same CBA. But the union's blind spot here is less revealing than the league's attitude toward the safety and well-being of its workforce.

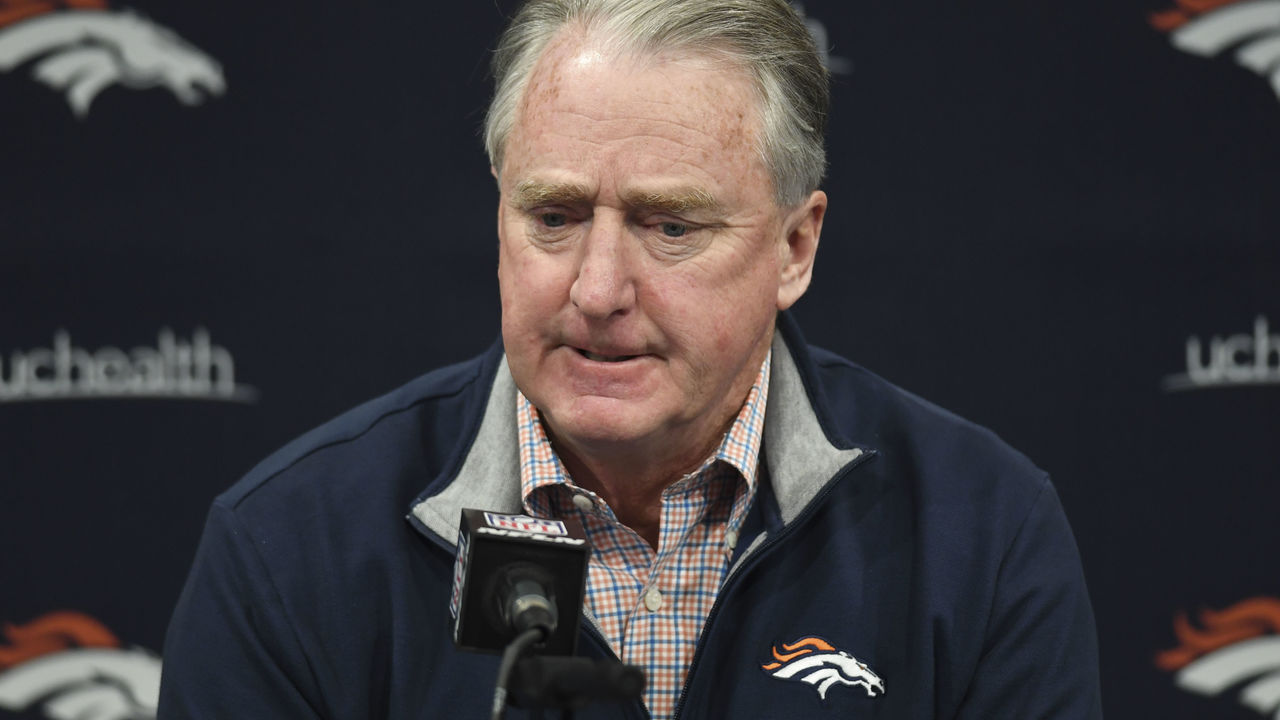

Let's be clear about something: Denver Broncos right tackle Ja'Wuan James tore his Achilles not by hang gliding, or by playing with fireworks, or by walking a tightrope between skyscrapers while blindfolded and smoking a cigarette. He was working out to prepare himself for a football season that doesn't begin for another four months. He was doing his dang job. The Broncos designated his injury as non-football-related anyway. They later rescinded millions of dollars in salary guarantees and released him.

The NFL, for good measure, piled on by sending teams a gratuitous memo reminding them that injuries "sustained away from the club facility, without authorization by club staff, will be considered a non-football injury for which a club will not be responsible for the player's compensation or other benefits." But this is a bad-faith reading of how that CBA provision has long been interpreted by both sides, as NFLPA executive director for external affairs George Atallah pointed out on a recent podcast with USA Today's Mike Jones.

"In most cases, there is a settlement or some sort of agreement if a player is working out in order to get better, under the coach's direction, away from the facility," Atallah told Jones.

This should apply to James, too, since he had been working out "under a program recommended to him by his coach," the NFLPA said in a memo crafted in response to the NFL's.

"I'm sure that locker room's waiting to see," NFLPA president and Cleveland Browns center JC Tretter told ESPN's Dan Graziano. "Because why would I prepare as hard as I can to come back at training camp in the best shape ever when, if something goes wrong, the team's going to throw me under the bus the first chance they get? So I think it's going to be an interesting decision by Denver on what they want to do because I'm sure the guys in their locker room are looking, and I'm sure guys in other locker rooms are looking too."

Understand: The CBA is quite clear that "no Club official may indicate to a player that the Club's offseason workout program or classroom instruction is not voluntary (or that a player's failure to participate in a workout program or classroom instruction will result in the player's failure to make the Club or result in any other adverse consequences affecting his working conditions)."

Yet the league's own memo - an unprecedented action, even for an outfit as paternalistic as the NFL - actively encourages teams to do exactly what the CBA says they cannot while also leveraging a player's injury to instill fear in its workforce. Keep that in mind the next time the league tries to tell you about its interest in players' health.

In his interview with Jones, Atallah followed the league's position to its logical conclusion.

"There are 29 weeks between the end of the Super Bowl and the start of training camp," Atallah said. "The logical extension of the argument that people are presenting is either a) nobody should work out for 20 of the 29 weeks, or b) the only place they should ever work out is at the facility. Those are the only foolproof ways for players to protect themselves if you're going to make the argument that they should only work out at the facility."

Obviously, players aren't going to stop working out during those other 20 weeks; they're professionals, and the nature of their work requires them to maintain their peak physical shape, even out of season. But this is why Atallah's point matters: As Tretter recently blogged, the league sought to make the offseason program mandatory during the 2011 CBA talks, but the players successfully negotiated to keep it voluntary.

(Coaches want it to be mandatory for obvious reasons. But owners - i.e., the league's negotiators, don't much care because the structure of the offseason program has no effect on revenues. That's something else to keep in mind here. And while agents are frequently quoted calling out the NFLPA, an agent's job is to represent a specific client's interest, rather than to take a macro view of collective labor dynamics.)

To put things in context, the NFL is basically attempting an end-around on the collective bargaining process simply because it thinks it can. Management has always counted on fans and voices in the football press to take its side, to see no difference between the playing of a game and the multi-billion–dollar business that game supports. And there's nothing trivial about that distinction: Even if your instinct is to scoff at the money players make and the workplace conditions they want for themselves - compensation that is far more precarious than most people realize - why root for someone like Jerry Jones to accrue more for himself instead?

"I think it's coming down to control - you'll do what we tell you to do, when we tell you to do it, how we tell you to do it," Tretter told Sports Illustrated's Albert Breer. "They haven't really heard players tell them no before."

It's the players, rather than the union's staff, who are pushing so hard to make voluntary workouts truly voluntary. A sizeable contingent of players is frustrated about being pressured to show up for something that's not required, even as these players do all they can to stay in shape and prepare for the season. The pandemic wiped out last year's offseason program entirely. By September, did anyone notice?

Many players on most teams showed up this week for Phase 2 of the offseason program, which includes some on-field work. But as Graziano reported last week, roughly half of the league's teams negotiated changes to their offseason schedules as a result of the NFLPA's push. That's a win for the players. Perhaps they're catching on to the idea that they have something - their labor - that can be weaponized, too.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.