How to think about football and analytics like a coach, not a fuddy-duddy

In the last two weeks, the NFL's analytics discourse finally reached a breaking point.

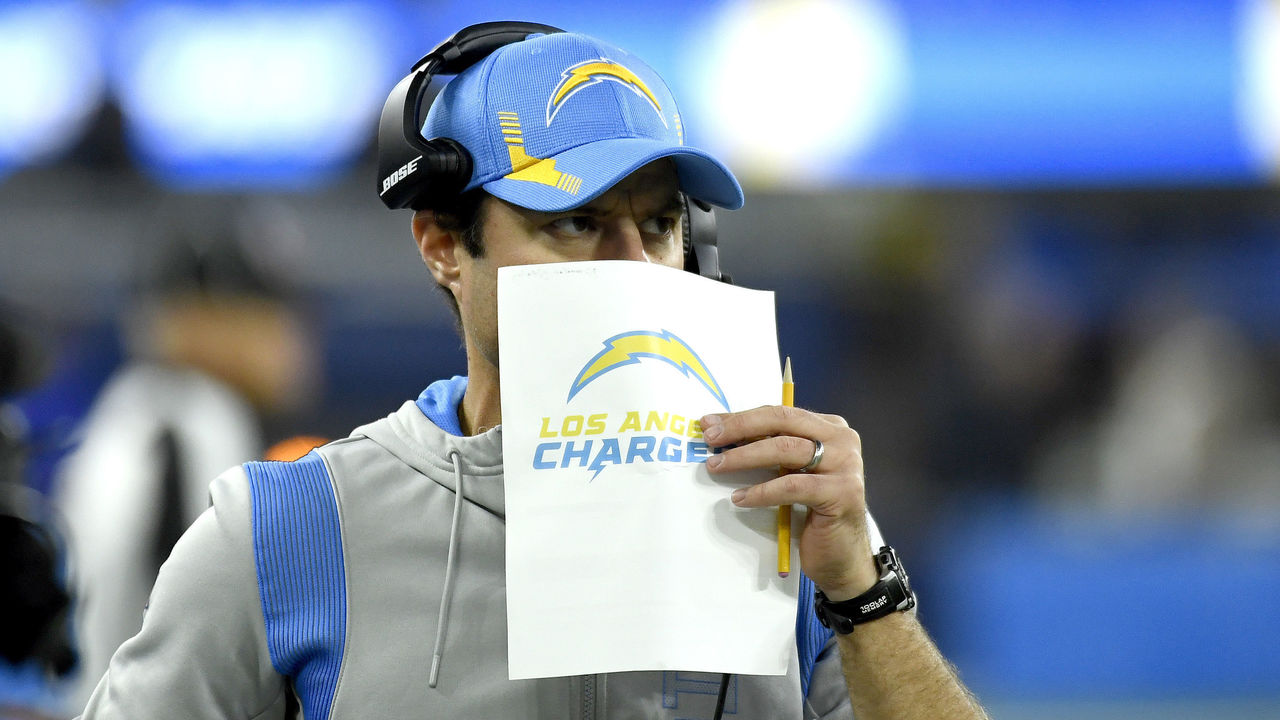

After coaches Brandon Staley of the Los Angeles Chargers and John Harbaugh of the Baltimore Ravens (among others) made a handful of unconventional decisions in games their teams lost, the Traditional Football Men began smashing the nerds' pocket protectors and shoving them into lockers.

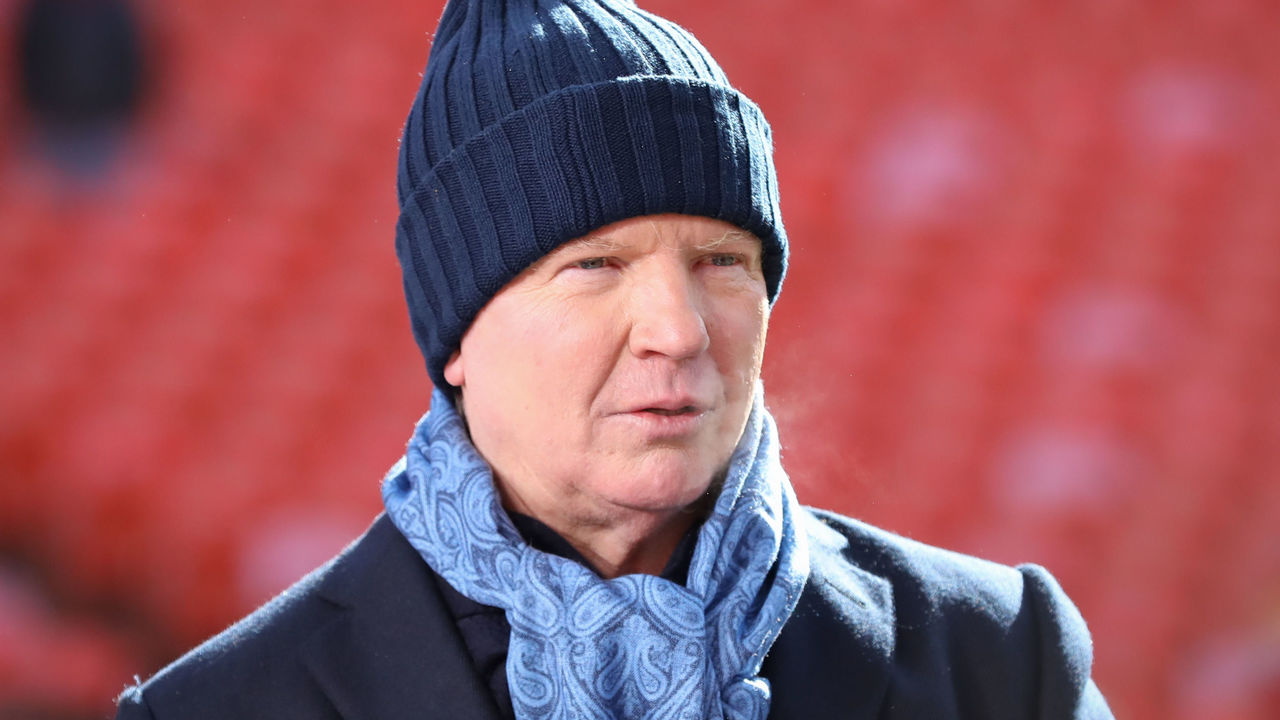

Here's CBS analyst Phil Simms, after Harbaugh's Ravens attempted a two-point conversion while trailing the Cleveland Browns by nine points with a little less than nine minutes to play in Week 14. Baltimore went on to lose, 24-22:

I want to see the analytics people come up and do the interview after the game. Tell me why you did it. When you're down two scores, the other team ... they change their play-calling and how they direct the game. So we don't put that into the analytics, I don't think ... I don't know, I don't care. We saw the Pittsburgh Steelers do the same thing (three nights earlier) against the Minnesota Vikings, and it kind of caught them.

Here's Fox's Howie Long, speaking to Terry Bradshaw, after Staley's Chargers went 2-for-5 on fourth downs - including a pair of failed attempts from the 5-yard line or closer - in a 34-28 overtime loss to the Kansas City Chiefs in Week 15:

Neither one of us can spell "analytics," but it took a beating tonight.

Here's Fox's Mark Schlereth, just before the New York Giants attempted a QB sneak and failed on fourth-and-1 from their own 29 while trailing the Dallas Cowboys 15-6 with 4:30 remaining in the third quarter in Week 15. The Cowboys quickly scored on their next possession and the Giants wound up losing, 21-6:

People will tell you the analytics will say go for it, but the analytics have never thrown one block or carried the ball one time.

And here's former Browns general manager Michael Lombardi on his podcast, impressively marking every imaginable cliché about analytics on his bingo card:

There's no consequences anymore. Ten years ago if you did this, you'd get fired. Ten years ago there was no social outrage, there was no this something called analytics that you could hide behind. "Well, I'm just going with the analytics." What does that mean? It's like the Wizard of Oz. Is he behind the curtain? Like, seriously. What is analytics? Like, who are these people? Are they some kid in a basement in Des Moines that's just run the numbers?

It's true that coaches and teams are increasingly being more aggressive about going for it on fourth down and attempting two-point conversions, and that these are trends rooted in data analysis (i.e., analytics). But what's striking is the pride these Traditional Football Men all take in not only failing to comprehend how any of this stuff works, but also that they can't even be bothered to try to understand it in the first place. It's just "I don't care" and "What is analytics?" and "Analytics never threw a block" and then spiking the football.

Other sports went through similar phases in which the fuddy-duddies shook their canes at all that newfangled math that fundamentally changed the way the sport was being played. It's always been harder to isolate the variables in a game as complex as football, but the data scientists are finding ways to do it - and the Traditional Football Men are reacting accordingly.

"I think it's part of the journey," Michael Lopez, the NFL's director of data and analytics, told me. "The reality is the landscape for football analytics has changed. We have easier access to data, we have bigger and better data samples, we have easier access to the tools that you would do analysis with. And you put that together and there’s a lot more discourse out there for folks to participate in."

So how does this analytics stuff work, and why has it become a such trend in today's NFL? Let's try to suss this out as simply and as clearly as possible.

OK, so what is analytics and why is it such a hot topic in football?

In a nutshell, analytics is information. Specifically, that information is data gleaned from statistical models and analysis that are used to provide better context to inform a decision. Concepts such as expected points and win probability, which both influence fourth-down and two-point aggressiveness, have been around for a long time. (For more on expected points and expected points added, read this.)

Those concepts are being applied more and more because every NFL team now has its own analytics department - a phenomenon that's only caught on beyond a handful of teams in recent years.

What's important to stress is that analytics are a piece of that decision-making process. Sometimes, that process will favor a decision that goes against what has long been what we're used to seeing when we watch football, such as going for it on fourth-and-goal from the 5 on the game's opening possession and later going for it on fourth-and-goal from the 1 on the last play of the first half when leading 14-10, as the Chargers did in Week 15 against the Chiefs.

Why would the process favor that? Why not just kick the field goal in both circumstances?

Because according to statistical models, the increase in the probability of winning the game by going for it in both circumstances exceeds what can be gained from kicking it. Take a look at this:

---> KC (0) @ LAC (0) <---

— 4th down decision bot (@ben_bot_baldwin) December 17, 2021

LAC has 4th & 5 at the KC 5

Recommendation (STRONG): 👉 Go for it (+3.1 WP)

Actual play: 👉 (Shotgun) J.Herbert pass incomplete short left to D.Parham. LAC-D.Parham was injured during the play pic.twitter.com/mUDKzepQce

Going for it on that initial fourth-and-goal from the 5 increased the Chargers' win probability by more than three percentage points over kicking a field goal, regardless of the outcome. Going for it and succeeding would put L.A.'s win probability at 54%; kicking and succeeding would put it at just 40%. Or, to put it another way:

To add to this, I think some coaches think of the 4 points (diff. between TD and FG) as already lost. The nerds maintain hope that those 4 points might still be scored.

— Cowboys Stats & Graphics (@CowboysStats) December 21, 2021

Traditionalists ask why nerds would risk 3 points. Nerds ask why they'd give up on 4. https://t.co/4mTIxwaE2D

OK, but when the Chargers go for it there and fail - as they did three different times - isn't that bad?

It is in terms of the outcome, sure. But look again at that tweet that lays out all those probabilities for the Chargers. Notice that the model bakes in the probability of success for either decision. A field goal in that scenario was 98% likely to succeed, while going for it had just a 35% success rate.

That's part of what Staley had to consider. But something else he had to consider - and that no doubt was part of his plan before kickoff - is that he was playing against the dang Chiefs, and that he figured he'd need to maximize every opportunity to score as many points as possible to win the game. And if it was possible to score seven points there instead of three, that was a risk worth taking. Patrick Mahomes isn't a dude you beat with field goals.

Is that how Staley explained it?

Basically, yeah. As he put it in a Zoom call with reporters the next day: "The real football people understand that what I'm doing is playing to the strengths of our football team, and what I'm doing is I'm trying to make the decisions that I think are going to win us the game - that are going to win us the game. And I'm ready to live with all that smoke that comes with it, and I've been very transparent about that."

Staley coaches a team with a terrific young quarterback in Justin Herbert. The Chargers' offense has a series conversion rate - the rate at which a series starting on first down produces a new first down or a touchdown - of 78.2%, one of the highest in the league dating back to 1999. Given that context, why wouldn't he try to maximize his chance to score seven points there at the risk of losing a likelier three?

What about that fourth-and-goal from the 1 at the end of the half?

Here you go:

---> KC (10) @ LAC (14) <---

— 4th down decision bot (@ben_bot_baldwin) December 17, 2021

LAC has 4th & 1 at the KC 1

Recommendation (MEDIUM): 👉 Go for it (+2 WP)

Actual play: 👉 (Shotgun) J.Herbert pass incomplete short right to K.Allen (D.Sorensen). pic.twitter.com/Wkwok4yq0S

Again, the numbers suggest going for it there was a reasonable decision. But an additional part of the context, as Frank Frigo of the analytics firm EdjSports recently explained to NBC's Peter King, is that "all the benefit of leaving Kansas City with the ball at the 1 if you fail is taken away because it's at end of the half.” For that reason, Frigo told King, he liked that decision less, but he didn't hate it.

So a lot of this is less about outcome than the process?

Yes! Exactly! You're starting to get it. A lot of people who are unfamiliar with how analytics is supposed to work tend to judge these decisions based on the outcome, which of course is overwhelmed by hindsight bias: If it works it was great; if it doesn't it was a mistake. But there's no way to guarantee an outcome.

Outcome is influenced by a bunch of factors like execution, the actual play call, luck, personnel, and weather. Analytics, as properly understood, is about factoring all of that and more into the process that influences which decision gets made. But a player or players can still fail to execute, or a defense can counter by making the right call or the right play to make a stop, or the ball can just bounce in an unfavorable way.

When the Ravens went for two and failed at the end of their Week 13 loss at the Steelers, they ran a terrific play, and tight end Mark Andrews was wide open. But Steelers edge rusher T.J. Watt had a fast-enough burst to charge hard at quarterback Lamar Jackson, forcing Jackson to alter his arm angle and rush his throw, which was off target and landed incomplete after going off Andrews' fingertips. None of that means the decision was incorrect. Harbaugh's explained all this quite clearly, in fact.

He has?

Yep. This is what he told reporters on a Zoom call Monday about how analytics influence his decision-making:

It's not how often you use it or don't use it; it's more to what degree does it factor in. We definitely don't follow the model 100% by any stretch of the imagination. The model tells you to go for two, it tells you to go for fourth downs a lot more than we did.

See that? Harbaugh isn't just making decisions because someone in some basement in Des Moines spit something out for him. Harbaugh went on to say that the use of analytics goes beyond in-game decisions. Even the process of watching tape - and using the eye test - is combined with data from the NFL's Next Gen Stats and the player-tracking data that's available to all teams. It creates "a body of information" that's analyzed and used to affect game planning. And on and on.

And the models can change, too, right?

Yep. As more information becomes available, there's more to be analyzed, which can lead to more ways of looking at things. Offenses are getting better than ever. As more teams opt to be aggressive on fourth down, those statistical models can and will change accordingly.

Why did Harbaugh go for two against the Browns when down by nine?

He explained that, too, actually, in his press conference right after the game:

You do it at that point in time because you're going to have to win a two-point conversion. So you understand if you get it or don't get it early where you're at going from there - how many possessions you're going to need, and what you're going to have to do. If you wait until the last two-point conversion and you don't get it, the game's over. You've lost. So you try it early, we're in a seven-point game, we know where we stand. We don't get it, we're in a nine-point game and we know that we need two possessions.

Has Phil Simms seen this?

*Shrugs*

What about the two-point conversion try at the end of the Green Bay Packers game?

According to the analytics, the Ravens would have been better off going for two after their previous touchdown, when they were down by eight. Doing so would have maximized their chances of winning in regulation, since going for two and getting it meant that kicking an extra point after scoring again would win the game, while going for two and failing would still leave them with a chance to go for two a second time to tie it.

Interestingly, though, Harbaugh was mic'd up during the game and he clearly consulted with his other coaches and players before deciding to go for two at the end of the game. He wasn't just reading off a sheet or listening to what the analytics wizard behind the curtain told him.

What did the analytics say about going for two and the win, though?

It was basically a toss-up, according to what Ryan Paganetti, a former Philadelphia Eagles assistant coach and analytics manager, tweeted after the game.

At the same time, kicking the extra point and going to overtime carries the 50/50 risk of the Packers winning the coin toss, after which Green Bay could get the ball and march up the field to score a touchdown against a Baltimore secondary that's been ravaged by injuries. The Ravens could lose without ever having the opportunity to possess the ball.

"You don't get a point for going to overtime in football," the NFL's Lopez said. "If this were hockey, it'd be a different story; like, kick the extra point, try to get it to overtime, you get half a win or whatever it is. You don't get that in the NFL; ties happen less than 10% of the time when you go to overtime.

"The attractiveness of getting to overtime does not make any sense, especially because you put players at further risk for injury, your load for your players is going to be higher come the next week. If you can get the game over with and win in regulation, there's a lot of value there. It's just easier to look at the failure and base your commentary on that."

Is analytics going to ruin the game like it did with baseball?

Nah. Sure, baseball has become an incessant sequence of strikeouts punctuated by home runs, but basketball has capitalized on the efficiencies of taking more 3-point shots as opposed to low-percentage mid-range 2-pointers, and that's been a good thing.

Similarly, as ESPN's Brian Burke has said, the growth of the passing game and the increased acceptance of going for it in high-leverage situations such as on fourth down or during a point-after conversion has made football much more thrilling to watch. The nerds bring the fun!

Despite all this talk about process, a lot of analytics-based calls have had favorable outcomes, too, right?

Yep. The first time the Chargers and Chiefs played back in Week 3, Los Angeles lined up to go for it on fourth-and-4 from K.C.'s 30 with 48 seconds to go in a tie game. A false start penalty backed them up 5 yards, but Staley opted to go for it on fourth-and-9 anyway. He clearly didn't want to give Mahomes the ball back without exhausting every opportunity to win the game while his team had the ball. The Chargers converted due to a pass interference call, and they were in the end zone two plays later. L.A. won by six.

When the Detroit Lions got their first victory, in Week 13 against the Vikings, they went for it on fourth-and-1 from their own 28 while leading by two with 4:08 to go. Ben Baldwin's model strongly suggested this was the right call. Jared Goff was sacked and lost a fumble, which seemed like a disastrous outcome. Yet even though the Vikings scored a TD two minutes later, the Lions still had plenty of time to march back up the field to win the game.

Heck, just last Saturday in Week 15, the Indianapolis Colts had Carson Wentz attempt quarterback sneaks on fourth-and-1 three times against New England: from their own 44 in the second quarter, from the Patriots' 38 in the third quarter, and from their own 43 in the fourth quarter. They converted all three and won the game.

Also, when trailing 20-7 with nine minutes remaining, Bill Belichick went old school and opted for a field goal instead of going for it on fourth-and-goal from the 7. Baldwin's model called that decision a toss-up. The anti-analytics dinosaurs must have missed that one.

How can some of these fuddy-duddies have their minds changed?

According to Lopez, the same way a lot of coaches became convinced: By emphasizing when this stuff has worked.

"The best way to convince football coaches to do anything is to show them film," Lopez said. "They maybe don't respond as quickly to graphs or tables or win probability or expected points. I think one of the things that's really helped get some of the coaches that maybe you would have perceived as against this stuff is to say, 'For every example that you're thinking of, here are all the examples where it worked.'

"I think it's funny that we're having this conversation after the Colts had three quarterback sneaks (on fourth down) against the Patriots. That's the kind of game that should be celebrated. That's the anecdote that we want to draw from, as much as what's happened to the Chargers and the Ravens.

"That's how the discourse has to happen. It's not about just saying, 'Hey, you're wrong.'"

Yeah, but what about the dude in his basement in Des Moines?

It's ironic that Lombardi used that metaphor in his anti-analytics rant. Dennis Lock, the Buffalo Bills' director of football research and strategy, earned his Ph.D. in statistics from Iowa State, which is about a 40-minute drive from Des Moines. Lock is now working to help inform the way the Bills actually make decisions. Lombardi is just a guy talking into a microphone - probably from his basement.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.