The Stingleys: A football story in three acts

On Sept. 21, 2019, Derek Stingley Jr. snared his first college interception, leaping to beat Vanderbilt's wideout on a jump ball for an underthrown deep pass. They crashed to the turf and Stingley's helmet wound up in the receiver's hands. Unmasked, he sprung to his feet smiling and waved his fingers to the crowd.

"He is keeping alive a wonderful football family name," Tom Hart, the play-by-play commentator, said on the telecast.

In 2019, Stingley was the freshman fulcrum and hometown headliner of LSU's last championship defense. The shutdown cornerback from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, nicked passes in four straight games during the Tigers' undefeated season. Stingley's dad, Derek, an arena football great and his mentor in the sport, secretly brought to the national final a vintage New England Patriots jersey, red with the No. 84 and their surname on the back.

The jersey belonged to Darryl Stingley, the wide receiver who was paralyzed on a brutal hit that made the Stingley name famous without defining it. A go-to deep threat for New England in his mid-20s, Darryl died in 2007 at 55, of causes that included quadriplegia and his spinal cord injury. He'd seen his son Derek establish a niche as a pro - defensive playmaker on a title team - and begin to coach.

Football's third Stingley is about to ascend to the NFL. theScore dubbed Derek Jr. a top-five talent in a recent mock draft while projecting he'll go No. 11 in Thursday's first round. That incongruity reflects the gap between his freshman transcendence and the quiet, injury-marred remainder of his LSU career. Where he'll land - where the Stingley story is to continue - is a captivating question.

Performance on the field shapes a family's football legacy. So do the stories that teammates tell about each successive player. It's Derek Jr.'s turn to apply his dad's teachings, transposing to the NFL the textbook cover technique for which he's praised. And it's his turn to try to affect people like his late grandpa did.

"Darryl's in my mind. I think about him quite often," said John Hannah, the Hall of Fame offensive lineman who was his New England teammate in the 1970s.

"He was a great example to me. I just always loved him. I appreciate who he is. And I hope his grandson lives up to being half the man that Darryl was."

The grandfather

On Oct. 3, 1970, the breakout performance of Darryl Stingley's freshman season helped power a road upset of Stanford, the country's No. 3 team. Purdue quarterback Chuck Piebes completed 15 passes, nine to Darryl. When the Boilermakers missed a field goal short in the first half, Darryl tackled the returner in the end zone, salvaging a safety.

Darryl Stingley was a natural in football and life, adept at everything he tried, said Gary Danielson, another Purdue QB who later played in the NFL and is now an analyst with CBS. Darryl could run, catch, leap, dive, dunk, dance, swim, and putt. One Sunday night with the Patriots, he convinced the patrons of a Boston seafood joint that Stevie Wonder was performing live, so persuasive was Darryl's impression of his favorite singer.

There was a duality to his playing style. Able to contort his body at will, Darryl rarely had to stretch to make spectacular grabs, so precise were his routes.

"Like a center fielder making everything look like an easy catch," Danielson said. "That was, to a tee, how Darryl played."

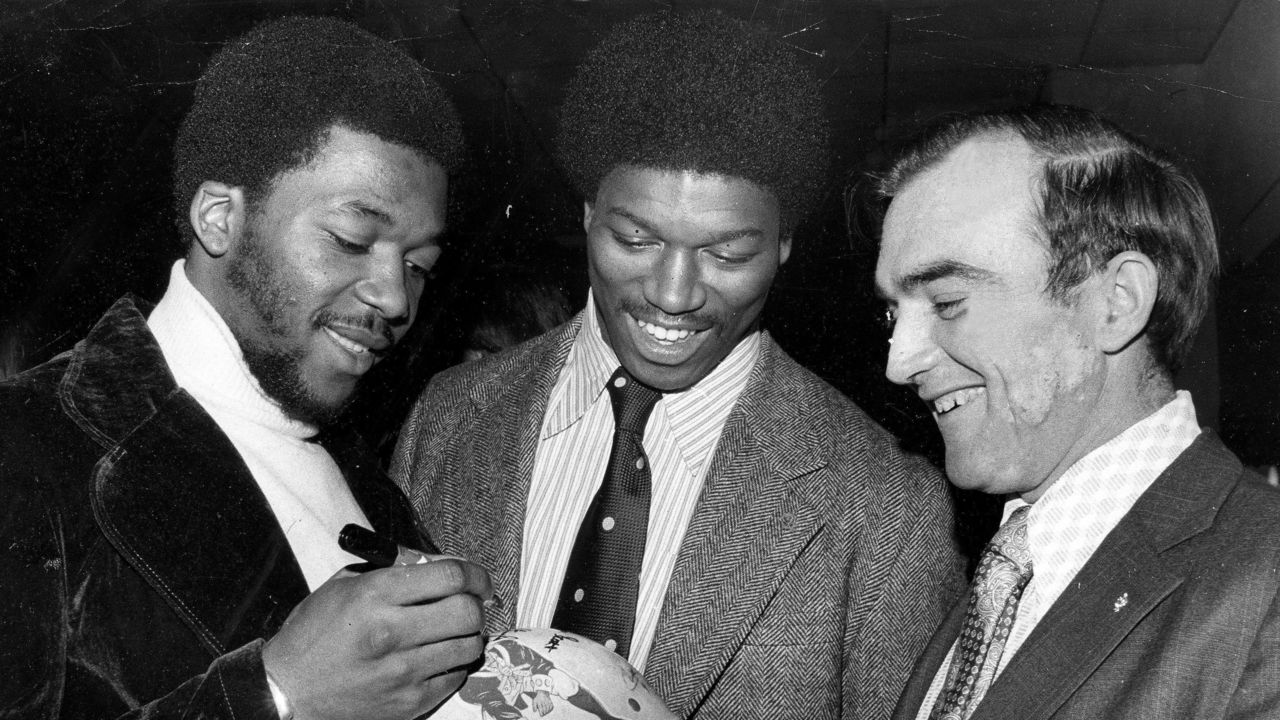

Born in Chicago in 1951, Darryl Stingley progressed from Purdue to the Patriots as part of the club's fine 1973 draft class. New England drafted Hannah fourth overall that year, snagged the future 1,000-yard rusher Sam "Bam" Cunningham at No. 11, and added Stingley at No. 19 with a pick acquired from his hometown Bears.

By 1977, Stingley's fifth season, he ranked in the top 20 league-wide in receiving yards and touchdowns. Dexterous at 6-feet and 194 pounds, he was QB Steve Grogan's favorite downfield target.

Teammates admired Darryl's discipline, dependability, work ethic, and warmth. He carried a boombox around at training camp to blare Stevie songs. He kept his hair combed, his shirt tucked, and his socks up in practice. He wrote color-coded notes in team meetings. He asked Pats cornerbacks to mimic in practice an opponent's tendencies that he'd noticed on film, and he yapped back at defenders who goaded him in games, showing pluck.

"He was fearless going after the ball," Hannah said. "He ran a lot of across-the-middle patterns. Those are tough patterns. If a quarterback throws the ball a little high, he's exposed wide open. That's what happened against Oakland. But he never cowered away from catching the ball."

In August 1978, Darryl ran a 15-yard slant route into the red zone during a Saturday preseason game in Oakland. He lunged to reach Grogan's overthrown pass. Momentum rendered Darryl defenseless as Raiders safety Jack Tatum, nicknamed "Assassin" for his violent hits, rammed his shoulder into Darryl's head.

The consequences were terrible. Crumpling to the ground, Darryl touched his head and then lay motionless. Trainers removed his cracked helmet and loaded him on a stretcher to be raced to hospital. A sick feeling engulfed the stadium, Hannah said, recalling that some Patriots cried in the locker room following the game. They learned the hit broke two vertebrae and damaged Darryl's spinal cord, paralyzing him from the neck down.

"It's a tragedy like a plane crash or a car accident, or anything that strikes somebody that you know. It takes the breath away from you," Danielson said.

"His body could do things that most of us can only dream of. In his prime, it was taken away."

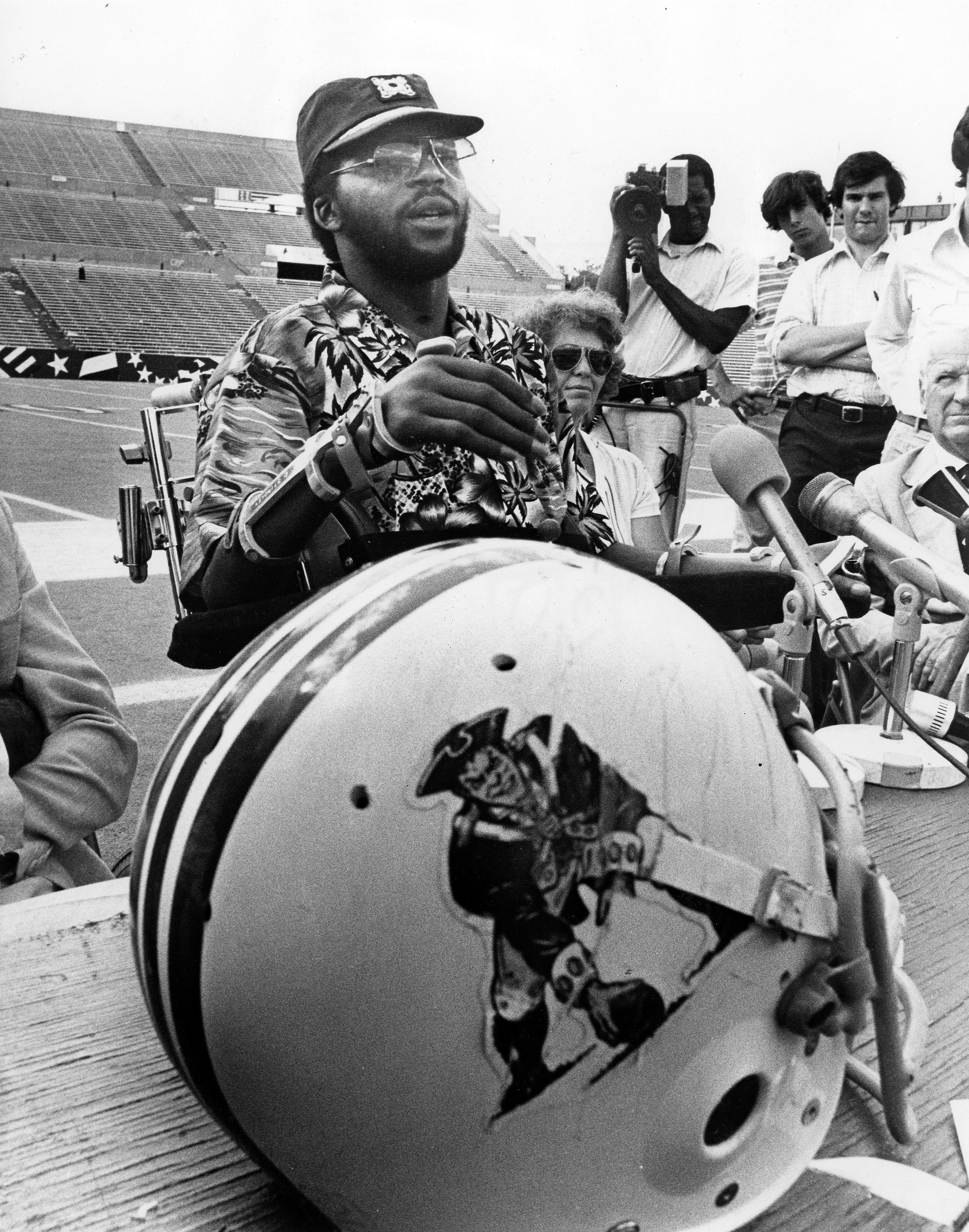

Football got safer after it upended Darryl's life. The Patriots stopped running that slant pattern. The NFL started to penalize helmet hits like Tatum's. League insurance paid for Darryl's medical bills and therapy restored some use of his arms. He drove an electric wheelchair and in 1982 described to The New York Times a recurring dream he'd been having, in which he stood in a stadium tunnel ready to charge onto the field before he woke up to face reality.

Paralyzed at 26, Darryl adapted to his fate when he stopped lamenting it, he once said to the Associated Press. He resumed and completed his Purdue studies, his agent told the Boston Globe for his 2007 obituary. He went to Bulls and White Sox games, chaired a spinal cord injury foundation, and ran a namesake nonprofit to uplift Chicago youth. Tatum died in 2010 having never apologized to him, but Darryl refused to hold a grudge.

Teammates admired his resilience and grace.

"I don't think I could have handled it had I lost my career that early in pro football. It was hard enough after 13 years," Hannah said. "But, gosh, to be as good as Darryl was and to have his career cut short like that … to watch him live life the way he lived it, with that grin on his face, it was an inspiration. It's something beyond belief."

Something unforgettable, too. During the 1978 season, the Patriots taped postgame phone messages to be played for Darryl in hospital. When Pats teammate Pete Brock retired in the '80s, he worked in IT for Hannah's pension investment firm, and the Hall of Fame lineman summoned Brock to his office monthly. Hannah would light a cigar and suggest they phone their old friend in Chicago.

"You wanted to be around a guy like Darryl. He never lost that," Brock said.

"Most of my memories are of Darryl at 18," Danielson said. "When you're 17, 18, 19, and you're being recruited, we all think we're the best, the brightest, the fastest. And then we saw somebody who was better than us at everything. Almost (at) throwing, to tell you the truth. He could do anything."

The father

On Aug. 21, 1999, right before ESPN televised a halftime segment on his bond with his dad, Derek Stingley dove to deflect a pass in Arena Bowl XIII, the defunct Arena Football League's championship game. His Albany Firebirds led the Orlando Predators 35-21. When Orlando threatened to score on fourth and goal, Derek broke up a slant route in the end zone.

Derek lived in an apartment complex in the unit below Eddie Brown, dad of Antonio Brown and the best receiver and player in AFL history, as voted by an expert panel in 2006. Stingley, a budding star defender who "could run like a deer," sought to learn from his Albany teammate, Brown said. They studied one-on-one matchups on film at home together and battled in practice at game speed, bodying each other with a ferocity that raised eyebrows.

"He would hit me. I would hit him. It'd be like: Damn, are you guys friends?" Brown said. "It was heated. But we had our mission. Our mission was to make each other better, and we wouldn't pull any punches."

In August 1978, Derek was seven and asleep in Chicago when his mother Tina, Darryl Stingley's wife and high school sweetheart, woke him to say she was departing for Oakland. Tina stayed there until Darryl was able to fly home. Around Christmas, Derek has said in past media interviews, he crawled on Darryl's chest in a Chicago hospital room and kneaded his fingers and arms, trying to stimulate movement.

Never told he shouldn't play football - only that he shouldn't play fearful of injury - Derek intended to suit up at Purdue but transferred to junior college. His prowess as an outfielder commanded MLB attention. The Philadelphia Phillies drafted him in the 26th round in 1993. Derek toiled in the low minors for three seasons, swiping 55 bases in 169 career games, but quit baseball in '95 with more strikeouts than hits.

It's something else to see LSU freshman CB Derek Stingley Jr. play in the CFP semifinals tonight. He wears No. 24, just like his father did for the Albany Firebirds 20 years ago. Here's Derek Sr. in the '99 ArenaBowl and with his daughter Isis before Derek Jr. was born: pic.twitter.com/B7zASE0bsv

— Mark Singelais (@MarkSingelais) December 28, 2019

The gridiron beckoned. Scoring a dozen return TDs the next winter for a Louisiana semi-pro club got Derek recruited to arena ball, the eight-a-side sport played inside hockey rinks on 50-yard fields with padded walls. Supercharged offenses routinely combined to score 100 points in a game. Derek didn't inherit Darryl's soft hands - "Couldn't catch a lick," Firebirds QB Mike Pawlawski said - but his speed made him a defensive weapon.

"Our coach had a very fast clock. You have to take that into account. But they timed Stinger in, like, the 4.1, 4.2 range running the 40 in Albany," Pawlawski said. "Everybody claims (to be able to run) 4.3. Very few dudes actually run it. He was a clear and plain 4.3 or better guy."

Derek joined Pawlawski and Brown on the All-Arena First Team in 1999, when Albany beat Orlando 59-48 in the Arena Bowl. He deflected a few throws in the title game, including a Hail Mary with no time left, on either side of ESPN's halftime feature. Over footage of Darryl taking in a Firebirds contest from his wheelchair, Darryl told the narrator, correspondent Jeremy Schaap, that watching his son play brought him joy not angst.

In 2001, Derek made the AFL's 15th anniversary All-Star team alongside Brown and Kurt Warner, the Iowa Barnstormers alumnus who became a two-time NFL MVP. Except for a stint on the New York Jets' practice squad, arena greatness didn't elevate Derek to the NFL. Instead, Brown said he lived in the moment and gave his all to the Firebirds, refusing to dwell on what-ifs.

"The superstars in the NFL, those guys are really, really, really special. You're not going to replace those guys. But 80% of that league, it's a razor's edge. You can be a guy who could make the team and play for 10 years, or not, just based on a coach's decision or a coach's impression of you," Pawlawski said.

"A lot of guys I played with in the Arena Football League - guys like Stinger - could have been on a roster in the NFL for quite a while had they gotten the right place, right time, just like life in general."

After he retired, Derek coached or coordinated the defense for teams that, thanks to arena ball's decline, no longer exist. The South Georgia Wildcats. The New Orleans VooDoo. The Pittsburgh Power. The Philadelphia Soul. He was coach of the year in 2008 in the AFL's minor league, AF2. Coaching the Shanghai Skywalkers in 2016, he tuned into the streams of Derek Jr.'s high school games on Saturday mornings in China, tracking his protege's progress.

Derek and Derek Jr. declined to be interviewed for this story, but Derek has explained before how he raised his son to excel at cornerback. He told Derek Jr. to walk backward at age four to master the motion. He taught him to tackle and defend jukes in the family yard in Louisiana. He fastened a diagram of pass routes to Derek Jr.'s bedroom wall. Derek Jr. watched a lot of game tape, and he took part in footwork drills that Derek devised for pros.

"There are clips of him with his dad coaching arena, and he's there training with 20-year-old, 25-year-old, 30-year-old guys," said Devin Taylor Jr., Derek Jr.'s friend and former teammate at The Dunham School in Baton Rouge.

"You see those old clips of Steph Curry shooting a basketball (as a kid) on an NBA court. It's just like that. It's second nature to him," Taylor said. "It's just something he feels like he's destined for."

The son

On Dec. 7, 2019, Derek Stingley Jr. ran in lockstep down the sideline with a Georgia receiver, shadowing the route so that when he turned to track the ball, it landed in his arms - like Jake Fromm meant to hit him in the numbers. That wasn't the QB's intent. But Fromm couldn't avoid Derek Jr. in the SEC title game, not then nor when he jumped an out route deep in Georgia territory, nabbing his second interception in a blowout win.

Those were the last picks of a college career that teemed with promise. Derek Jr. was the nation's top recruit in the class of 2019, the whiz kid who intercepted Joe Burrow ahead of a bowl game - LSU invited him to December practices when he signed his letter of intent - before he was eligible to play a down. His six interceptions as a freshman led the SEC. Among cornerbacks, Pro Football Focus graded his 2019 season the best in the country.

"DBU" is tattooed in red on Derek Jr.'s right tricep, saluting LSU's record of producing All-Pros in the secondary, from Patrick Peterson to Tyrann Mathieu to Jamal Adams to Tre'Davious White. Draftniks and peers foresee that potential in him too. Before LSU won the national title and Burrow was selected first overall in 2020, he said Derek Jr. already was good enough to go in the first round.

That potential persists, but his momentum sputtered. Leg injuries limited Derek Jr. to 10 appearances since his freshman season. Opposing QBs didn't challenge him as often. His play rarely impacted the scoresheet, and not at all from last October onward, when Lisfranc surgery on his left foot ended his junior year prematurely.

"(2020 and 2021) didn't match up with what he did his first year. But his first year was his most healthy year. I think for all of those NFL guys, your health and your ability to compete every single week, and be at your best physically, is always the No. 1 challenge," said Neil Weiner, Derek Jr.'s high school coach at The Dunham School.

"When he's healthy, there's nobody better than him."

When Taylor played at Dunham, Derek Jr.'s elite traits - the fluidity, the sure hands, the speed to rival his dad in his prime - coalesced on one memorable snap. Doubling as a receiver during his senior year, Derek Jr. palmed a slant pass while planting his foot to change direction, freeing space for him to sidestep a linebacker and race from midfield to the end zone untouched.

Adults couldn't upstage him, either. When Derek Jr. was 16, he lined up in practice opposite Chris Briggs, the 6-foot-5 former Division I receiver who helped Dunham prepare for a state playoff game. Bested by Briggs in Monday's drills, Derek Jr. reviewed the practice film with his dad and returned Tuesday to lock him down.

"Some things are God-given. But I'm a firm believer in: hard work beats talent when talent doesn't work hard," Taylor said.

"Derek, he has both. I believe it's a combination of his genetics and him putting in hours upon hours of work, man. Him and his dad, they were inseparable, and his dad always stayed with him - always made him work."

As the draft neared, Derek ran 4.37 in the 40 at LSU pro day, suggesting his foot's alright. The retired teammates of his dad and grandpa contextualized the magnitude of his next step. By shining in the NFL, Brown said, he'd make good on the opportunity that eluded Derek Sr. and was stripped from Darryl. On the off chance he slips in the first round, Brock mused, "wouldn't it be wonderful if he fell to the Patriots?"

"As a former player, I don't root for teams, because teams are built by management. I root for dudes. Dudes that I like," Pawlawski said. "I don't know Junior. I haven't met him. I know his father. I know what an amazing and wonderful person he is and how much I admire and respect him. Wherever Baby Stinger goes, I will be a huge fan."

Him and Weiner both. The Dunham School retired Derek Jr.'s jersey last summer. Dunham's annual athletics dinner is Thursday, and organizers plan to screen the first round of the draft. Weiner said he'll be in Las Vegas at the Stingley family party, celebrating the kid who used to give piggyback rides to Dunham kindergarteners, humble despite the crush of attention he got from the wider football world.

It's what he was destined for.

"I know his grandfather has a big smile on his face up in heaven," Brown said, "watching his grandbaby do what he's getting ready to do."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- NFL Week 16 Prop Party: How to back Prescott in crucial game

- Injured Adams likely to remain sidelined vs. Falcons

- Kelce ready to give 'everything I got' in potentially final 3 games of career

- Week 16 anytime TD bets: Metcalf highlights 5 value picks

- Tua's time is up. Now the hard part starts for the Dolphins