How top QBs can lead the way on fully guaranteed deals across the NFL

The NFL is famously the only major sports league in North America that does not customarily guarantee the full amount of player contracts. But contrary to popular belief, the players' unions in the NBA, MLB, and NHL did not establish a pattern of guaranteed deals through the collective bargaining process. Instead, individual players used their negotiating positions to secure guarantees across multiple seasons. That set a precedent that other players soon followed.

All first-round picks now receive deals with full guarantees, but the length is set at four years (with a team option in Year 5), and the salary terms are non-negotiable and well below market value. Any undrafted or veteran NFL player is free to broker a multi-year, fully guaranteed, market-level contract like the one the Cleveland Browns gave quarterback Deshaun Watson in March. But several structural problems typically prevent this from happening, and that probably won’t change any time soon.

Watson's deal was indeed an eye-opener - and not just because he still faces lawsuits from 22 women who say he committed sexual misconduct or sexual assault. The terms of the contract - five years, $230 million, all fully guaranteed - broke all sorts of financial norms and evoked strong reactions from around the league.

NBC's Peter King reported that "the guarantee for Watson stunned GMs and club presidents." Baltimore Ravens owner Steve Bisciotti called the deal "groundbreaking" before quickly adding that "it'll make negotiations harder with others." NFLPA president JC Tretter blogged that the deal could be "a "turning point" in creating a new standard.

If only if were that simple.

For starters, Watson had unique leverage. He's one of the league's best players at a position where quality tends to be in short supply. And before the lawsuits were filed, he had made it clear he no longer wanted to play for the Houston Texans, who were eventually compelled to trade him. Once the first of two grand juries decided not to criminally charge Watson, the bidding war escalated - and the Browns were willing to fork over six draft picks in addition to handing him a long-term contract with full guarantees.

"Watson was effectively operating as a free agent given his situation, and we don't really see top-five, top-10 quarterbacks ever reach free agency," Pro Football Focus salary-cap analyst Brad Spielberger told theScore.

The closest analogue is Kirk Cousins, who defied convention by bargaining for a three-year deal with $84 million fully guaranteed when he joined the Minnesota Vikings in 2018. Like Watson, Cousins had unique leverage: He was an unrestricted free agent who had played on back-to-back franchise tags during his final two seasons with Washington.

"The talk in our locker rooms," Tretter wrote, "was a hope that other top free agents - especially QBs who were negotiating immediately after Cousins - would demand the same."

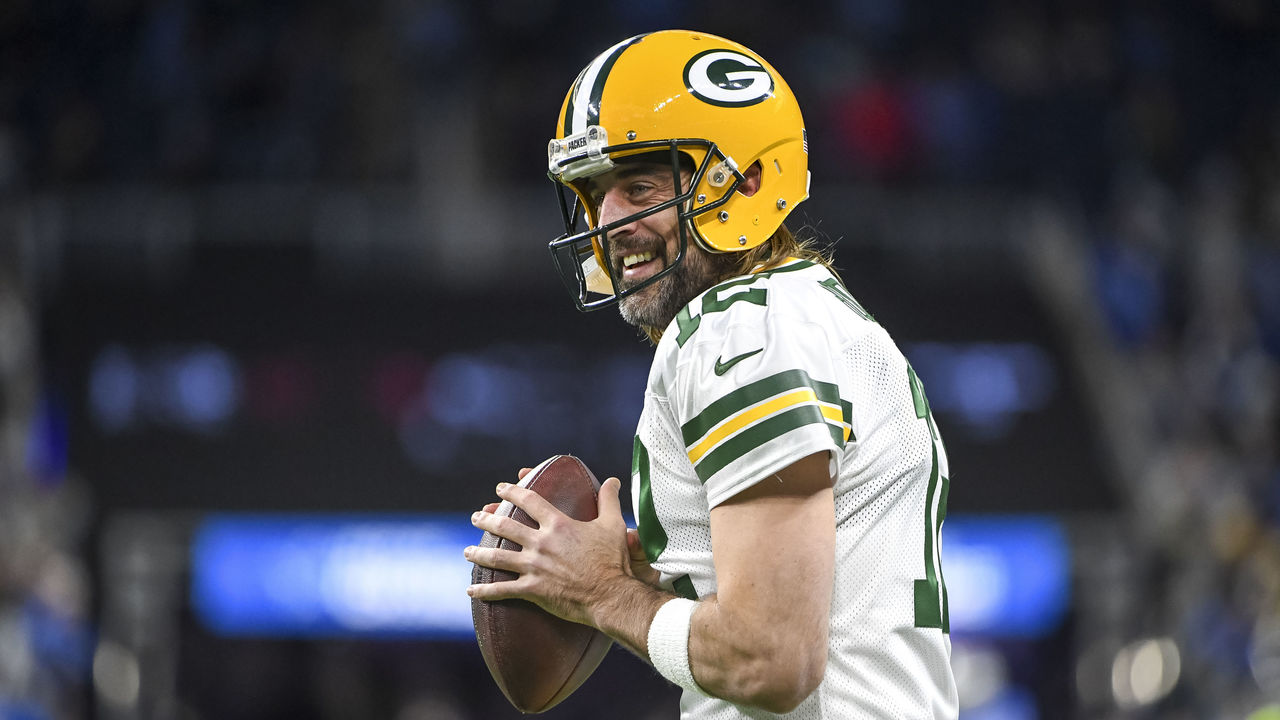

This didn't happen, however. Over the course of the next year or so, there indeed were rumblings that passers like Aaron Rodgers and Russell Wilson might insist on an unusual structure such as a full guarantee or an unprecedented trigger that tied their salaries to growth in either the salary cap or the quarterback market. In the end, both opted for traditional deals that substantially raised the bar for what star quarterbacks stood to earn while maintaining the status quo.

The numerous deals with star QBs that were completed before Watson joined the Browns - including Watson's initial veteran deal with Houston - all likewise adhered to relatively similar parameters, even as they featured average annual values of at least $39 million. This list includes contracts for Patrick Mahomes, Dak Prescott, Josh Allen, Matthew Stafford, and Rodgers again. Tom Brady is of course an exception, but Brady has been fine with playing for far less than top-of-the-market value for more than 10 years now.

Derek Carr had the first crack at capitalizing on Watson's full guarantee, but he too signed a contract extension in April that will average $40.4 million with nothing guaranteed beyond 2022. As a prominent player agent explained to theScore on the condition of anonymity, Carr's agent probably leveraged the lack of a guarantee into a much higher average per year than Carr might be worth.

"Is Derek Carr really worth 40?" the agent asked. "Is he probably more of a 35 guy? I would say so. The leverage point of the guarantee does help you get more money."

This dynamic speaks to a paradox at the root of bargaining for multi-year guarantees: negotiating for one typically means sacrificing real money. And because most star quarterbacks understand their teams aren't likely to cut them after signing them to a mammoth contract, it's often better to take the additional money, since the entire contract is likely to function as effectively guaranteed anyway.

"There's two components - and nobody ever talks about this," the agent said. "It's cash and structure, and it's hard to get both. Deshaun got both. Deshaun was basically a free agent, he had unusual leverage, and he had a team that was beyond desperate."

Carr also ran into a major structural factor that favors owners: the so-called funding rule that's baked into the CBA. This rule mandates that any deferred guaranteed money (minus a $15-million deductible) be placed into an escrow account at the start of the following league year. Browns owner Jimmy Haslam, for example, will have to cut a check next March that sets aside $169 million of the remaining $184 million he owes Watson.

The funding rule, which had just a $2-million deductible in the previous CBA, dates from a time when some NFL owners had genuine cash-flow problems that affected their ability to meet payroll. But it's long provided an excuse for owners to avoid paying large, multi-year guarantees to players.

These days, thanks to the exponential growth of national television revenues, owners bring in more than enough money to cover team payroll and benefits before they so much as sell a single ticket. But unlike newer billionaire owners such as Haslam and David Tepper of the Carolina Panthers, the league's older, family-run franchises like the Las Vegas Raiders often aren't liquid enough to part with nine figures in cash.

This context is important to remember when Justin Herbert of the Los Angeles Chargers and Joe Burrow of the Cincinnati Bengals are eligible to bargain for second contracts next March, after the conclusion of their third seasons. Both quarterbacks play for franchises owned by so-called "cash-poor" owners (Dean Spanos and Mike Brown, respectively) who may not be able to front the dough for a monstrous fully guaranteed deal. Kyler Murray, who is currently eligible for a second contract, faces a similar scenario with the Bidwill family that runs the Arizona Cardinals.

(That's not to suggest that any of these inheritance babies deserve your pity, by the way; it's simply to demonstrate the ways the league's financial system is set up to limit a truly free market for player compensation.)

Those three owners have the additional option of riding out their quarterbacks' fifth-year options and then using the franchise tag to control their rights. But the tag gets progressively more expensive each year it's used, as Cousins discovered to his benefit and as the Dallas Cowboys learned by waiting so long to extend Prescott.

Lamar Jackson, who is also eligible to bargain for his next deal, is a bit of a wild card. Unlike Baker Mayfield, whose performance slipped in his fourth season to the point that the Browns sought to replace him, Jackson benefited by waiting things out. He very well could land an extension in the $40-million range, but he's also negotiating without an agent, so there's no telling what parameters he might prioritize. At the same time, Jackson's run-heavy style of play might also make the Ravens hesitant to commit to significant long-term guarantees.

"I could see (the Ravens) continue a recent trend of theirs, which is stronger guarantees for lower total value, which perhaps pushes fully guaranteed money into Year 3," Spielberger said. "But I don't think he'll get both the big-time value and full guarantees into Year 3, Year 4, etc."

Spielberger thinks the rolling guaranteed structure that Mahomes and Allen have in their deals, which triggers a future year's guarantee at the start of a given year, might soon become more common. But the agent who spoke to theScore suggested that if, say, Burrow and Herbert wanted to establish a guarantee standard for others to follow (in lieu of top-of-the-market money), they might want to bargain for a shorter deal with a length of, say, three years. A contract like that would also allow the player to return to the bargaining table sooner, helping them keep up with any growth in the market.

This agent thinks also it's possible for guaranteed deals to become a precedent that can trickle down to become attainable for star players at other positions.

"But it's got to happen multiple times at the quarterback position first," the agent added.

There are only two questions left to ask, then: Will multiple quarterbacks be willing to use their significant leverage to prioritize setting a standard of a full guarantee across multiple years? History says no. But what about the future?

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.