Larry Csonka on the '72 Dolphins and NFL perfection: 'I guard it jealously'

Fifty years ago, the Miami Dolphins fielded the NFL's best offense and its stingiest defense. They ran the ball up the gut and recorded three shutouts while holding four more opponents to 10 points or fewer, including when they triumphed in Super Bowl VII to finish the 1972 season undefeated.

They're proud of the achievement. Legend holds that the '72 Dolphins pop Champagne annually, toasting the exclusivity of their famous feat every time the league's last unbeaten team loses.

"The Champagne toast is (more) of a cold beer celebration, in my opinion. It's the players talking to each other because it keeps us in an active mode, even though some of us have been retired for 40-some years," Larry Csonka, the Hall of Fame fullback who was Miami's rushing leader in '72, said in a recent interview.

"We're the only ones sitting on top of the mountain," Csonka continued. "When someone starts getting up close, we start to get nervous. We start to talk to our teammates about it and get their opinions.

"Together, we get competitive again."

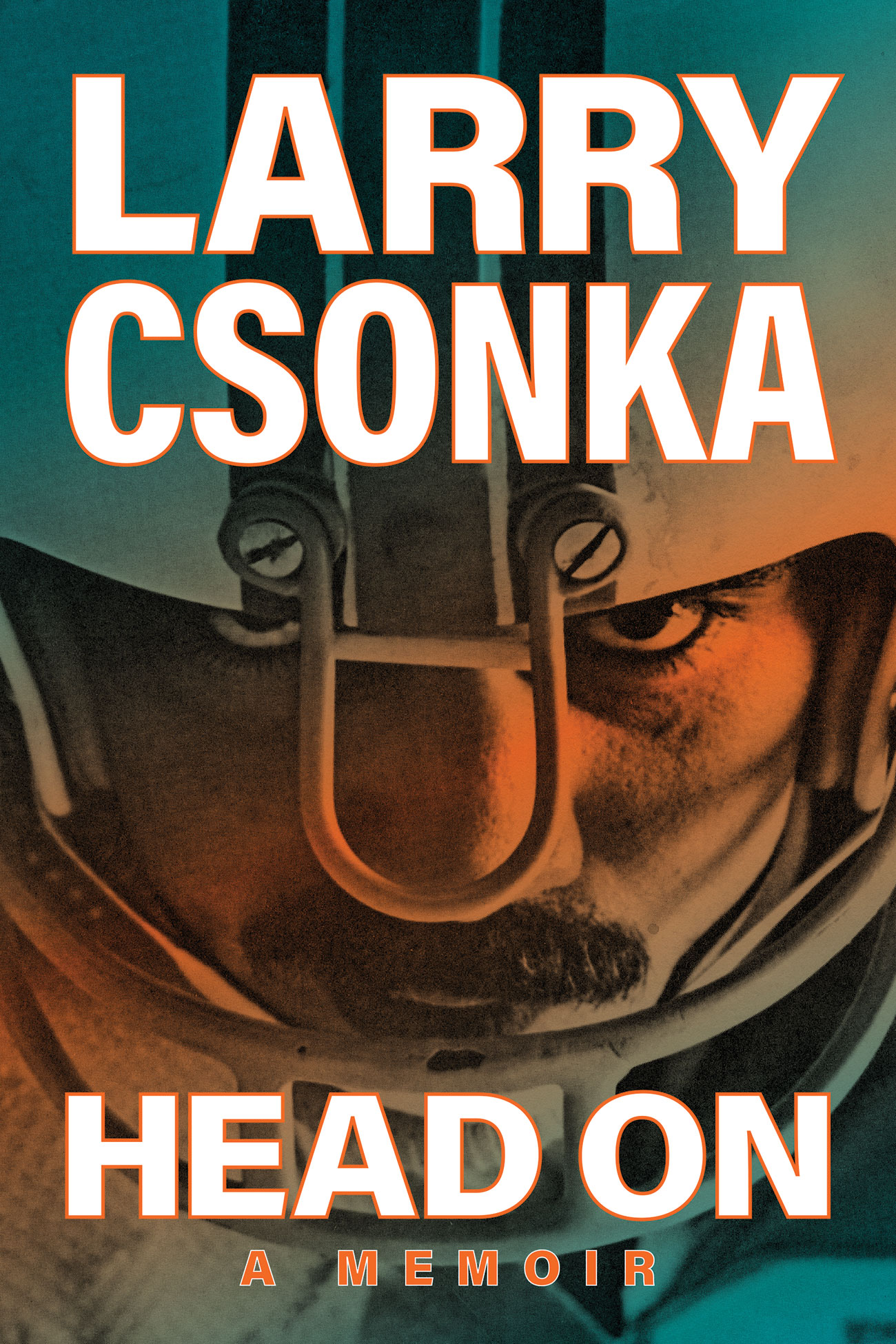

Csonka is 75 years old and wrote a memoir, "Head On," that is in bookstores Tuesday. The book explains how the Dolphins summited the peak in '72 and chronicles his travels away from the gridiron.

Csonka grew up befriending crows on his family's Ohio farm. As an All-American at Syracuse, he watched classmate Joe Biden wheel around his neighborhood in a green convertible. Csonka shot pool with Elvis at Graceland and evaded sniper fire over Vietnam when he visited troops. While filming the Alaskan adventure TV series he used to co-host, Csonka was stranded at sea overnight and signed a football for his crew's Coast Guard rescuer.

He reminisces in "Head On" about the perfect season. Miami dominated with a smashmouth run game that minimized mistakes and monopolized possession. The legendary late coach Don Shula led the Dolphins to a 14-0 record and three playoff victories, which set the club on course to repeat as champions the following year.

Csonka spoke to theScore about Shula's genius, tailgating with fans throughout the unbeaten run, the New England Patriots' brush with perfection, and the faint possibility that some team will run the table in a 17-game regular season. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: What, to you, is the legacy of the '72 Dolphins?

Csonka: It's the only perfect team to ever happen in 100 years. To attain that perfection from Game 1 all the way through to the championship, even in the '30s and the '40s, it didn't happen. Since then, they've added more games, so it'll be even tougher.

The power running game is where I lived and that's what we were famous for: being a ball-control offense, not giving the other team's offense a chance to have the ball much, and being able to take it away with a great defense. Those things added up to a perfect season. But the power running game has faded considerably. The position I played, fullback, is mostly nonexistent.

The emphasis has been put on the passing game, and why not? From a spectator standpoint, you see a man throw a ball and a man run down the field and make a great catch - you're seeing it all at face value. The power running game and the intricacies of coordination between offensive linemen and running backs are hard to see from the stands, and probably even harder to understand if you're not an avid fan.

You and Mercury Morris made NFL history in 1972: you were the first teammates to rush for 1,000 yards apiece. What made you, Mercury, and Jim Kiick (who rushed for 521 yards) a great backfield trio?

The relationship between Jim Kiick and Mercury Morris. Mercury and Jim were substituting every other play or so. It's hard to accept that you're not solely the first-team guy at (running back). But to split that and not get envious of each other - they both aspired to play more time than the other, but they understood each other's positions.

It's not just having the talent on the field. It's also the collaboration between the players and the intelligence factor of knowing what to do and when to do it - and not letting your ego get in the way.

That's what Jim Kiick and Mercury Morris did. They got to be quite close and ended up being great friends even after we retired. Right up till the time that Jim passed (in 2020), Mercury was calling on him two or three times a week.

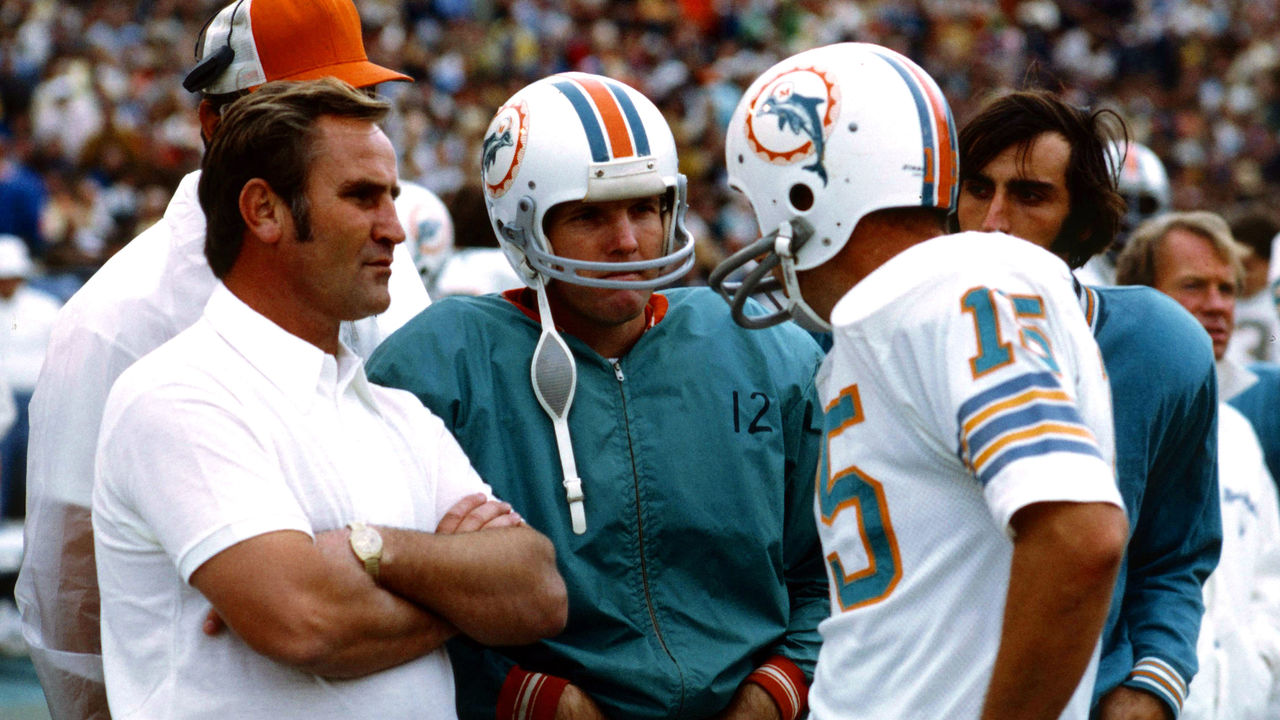

Why did Don Shula win more NFL games (347 between the regular season and playoffs) than anyone?

Details. He called it "the winning edge." You not only use force on the opponent, but you use intelligence. You persist on the details. Nothing's too small to overlook.

He knew we were playing (Super Bowl VII) in Los Angeles, and he wasn't familiar with that stadium. When we had Sunday off a week ahead of the game, he flew out in the middle of the night and sat in the stadium during the time that the game would be played. He charted the sun and where it was at - what the conditions were on the field in (relation to) where the sun was.

He didn't want the sun in his receivers' eyes and certainly not in his quarterback's eyes. That's how minute Don Shula would get on the details.

The worst thing you could do if you were playing on a Don Shula-coached team - believe me - was go through the motions. You knew it, but you were half there in practice. The very second he sensed that, he became a dominant head coach and would get in your face about it. He kept his practices short and to the point, and everyone was full attendance and full-throttle with your brain.

Miami's 52-0 win over New England in 1972 was an all-time beatdown. That was one of three shutouts the defense put up that season. Why was scoring on them so difficult?

The intelligence factor. That was one of the smartest defenses, IQ-wise. When (Shula was hired) in '70, we took a series of tests. Physical tests: we all ran 40s for time and had a conditioning rigamarole that we had to go through. We had to lift weights and be documented on what we could lift. Then we took a basic intelligence examination to make sure we could all pass that.

The absolute last team in the NFL (when Shula became head coach) was the Miami Dolphins. We were at the bottom of the pit. He did not expect to inherit as many smart and talented players as he got. He was greatly surprised and happy about it. Then he put a spectacular coaching staff together.

The Dolphins were blown out in the coldest Super Bowl ever to end the 1971 season, then won the warmest Super Bowl ever the next year. How did losing Super Bowl VI prepare you to win Super Bowl VII?

It goes back to the head coach. After we lost Super Bowl VI, he stood before us and said, "I want everyone to remember this moment."

On the first day of camp when we got back, we watched the film of the previous Super Bowl. He stood before us again and said, "We're going to draw on this throughout the course of this year. We're going to remember this game and what the details were that we overlooked." Jim Kiick looked at me and winked his eye in the meeting and said, "Buckle up." (Laughs) I thought, "Well, he's demanded a lot since 1970. Now he wants us to double down."

He said we'd use heat as an asset. We would practice longer in the hot part of the day. Go without water breaks. Do the things we had to do to make ourselves camel-like, so that we would have a winning edge in a heated game in the Orange Bowl. That's when I said something like, "That's if we don't die." He said, "My office after the meeting." (Laughs)

I'd like to tell you that the '72 team was far above and a lot stronger than the other teams. It was not. It was better coached and it was more efficient. It carried a winning edge because it paid more attention to detail.

You write that the '72 Dolphins' success unified a fractured city and changed Miami for the better. How so?

When Don Shula came to the Dolphins, we were the losingest team in the NFL and were kind of second-class citizens in the city of Miami. Game day, if we got 25,000 or 30,000 people in an Orange Bowl that held 70,000, that was doing pretty good.

When we started to win in 1970, the crowd started to get bigger and bigger. Finally, it was standing room only. The fans and the people were very excited because there was winning football happening right in their midst.

Our fans were from all walks of life. They started to come in early and park in the same lot we did. We got to intermingle with the fans. After the game, they would stay late to the point that the Miami police would show up and say, "Folks, you've got to cut this out. We've got to lock up the lots."

We talked to the mayor and the mayor decided to extend it so that we could stay there as late as we wanted. They would wait for us to come out of the locker room after getting a shower and dressing, and then we'd sit around and have hot dogs and cold beers and talk about the game with the fans. Tailgating got to be quite a thing.

That tremendous combination of fans represented a community that was ethnically divided. The racial situation was at a crisis. In the early '70s, riots were going down in lots of places. I think it was a (process of) coming together with a concentration on sports, and finding out that we're all Americans and we all have something in common in the football arena. The Orange Bowl was a giant blending pot.

When 15,000 of your fans come to the airport halfway through the season to welcome you back on Sunday night after you had a victory or close call on the road, you know you've got some avid support. They go from being fans to sort of like family. You start to know them by name. It was a different world and it was very celebrated. I think that helped an otherwise strained situation in Miami.

Tom Coughlin, the retired NFL coach, was your college teammate at Syracuse in the 1960s. His New York Giants ruined the 2007 Patriots' would-be perfect season. What was on your mind throughout that season as New England came close to perfection?

(Laughs) I'm sure you know exactly what was on my mind. I was hoping they wouldn't do it, and so were many of my teammates. That's why the '72 team lives in infamy. Each year, when some of the teams are 4-0, I start to hear from my '72 cohort. They start calling me on the phone, putting the hex on the team that looks like it might be going undefeated.

The Patriots did a fabulous job. They went through that season and it got right down to the wire. (David) Tyree made that catch at the end of the game with the ball on the side of his helmet that made the difference. I jumped out of my chair in the rec room watching the TV set and about brained myself on the fan.

It was a great, tense moment and it went the way I hoped it would go. Tom came through. I constantly remind him. We talk about it every once in a while.

Several of your '72 teammates have posthumously been diagnosed with CTE. In the book, you reference a New York Times headline about their lives and deaths: "For NFL Perfection, a Steep Price." How have your teammates' health issues shaped how you view football today?

I think (the NFL is) doing what they can do to lessen that. I think it's a much more safe game, because they've taken the direct hit - targeting - and put in rules to protect the players. The pads they utilize and the helmets - oh, my gosh, it's three times better than what it was 50 years ago. There's no question. They're very shock absorbent.

They're doing everything they can do rule-wise to minimize that situation. It appears it's going a very positive way because of the rule changes and the quality of the equipment increasing. Hopefully, that will become a small factor. But I think in the days gone by, of course, it was a much larger factor. Some of the fellas, I believe, suffered early demises because of that.

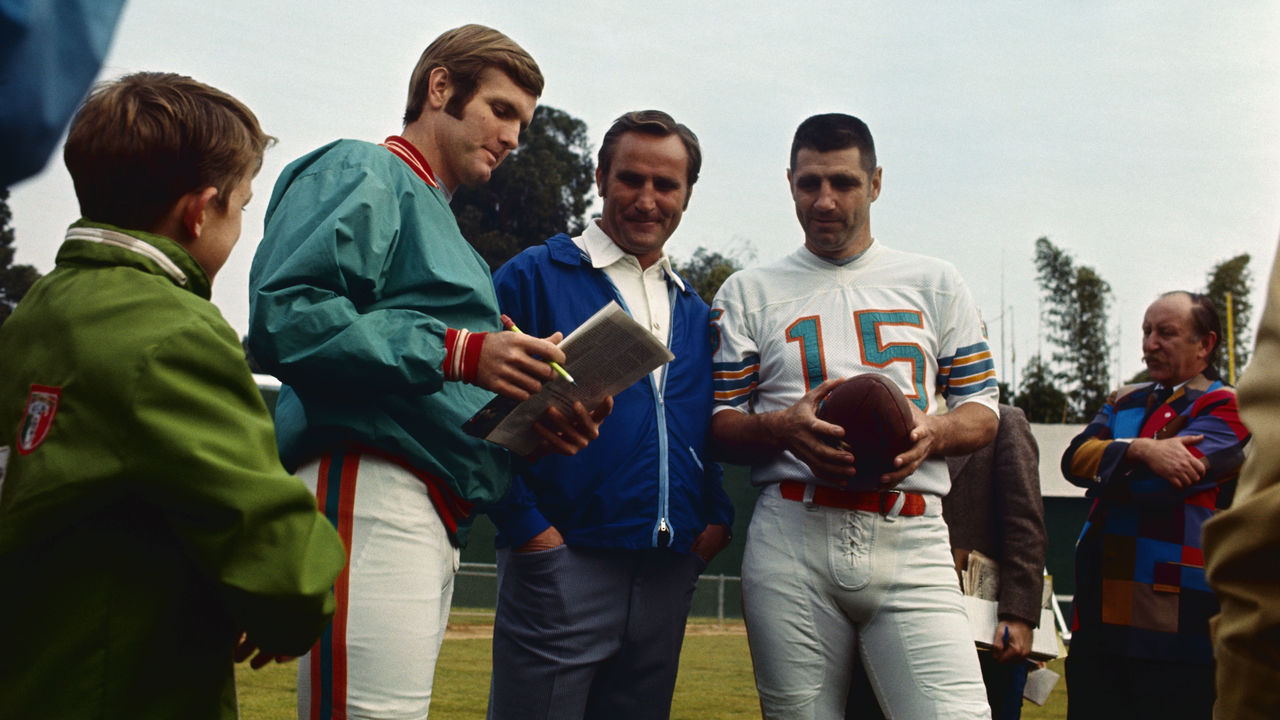

The '72 Dolphins bought a rocking chair for Earl Morrall when he was acquired to be the backup quarterback. Morrall was 38 but started most of the season after Bob Griese broke his leg. Where does that rank among all-time QB accomplishments - him stepping in to preserve the perfect season?

There was a guy who was cut out to do that, and his name was Earl Morrall. He'd been to three or four teams before he stopped at our place. He'd worked with Shula in Baltimore backing up (Johnny) Unitas and stepped in and accomplished some very positive things. (Morrall won NFL MVP in 1968 when Unitas was limited by injury.)

At that time, to play at that age and have been with three to five teams, we considered that grandpa-itis. We all got together and bought a rocking chair.

Earl walked in and saw the rocking chair and absolutely loved it. When the joke was over and they were going to move it out, he wouldn't let them do it. He would sit there and put his feet up and look at his playbook and talk to us and hold court. Instead of shrugging that off and making a joke and letting it pass, he wore it like a badge of honor.

There was no radio in Earl Morrall's helmet like there is today. He had to remember things. If he'd been paying attention, we were going to win the game. If he hadn't (paid attention) in the meetings - as a backup player, if he wasn't on the spot ready to go - we would have lost that game. But instead, we won.

A lot of fans remember kicker Garo Yepremian's late gaffe in Super Bowl VII. What else should people know about Garo?

We depended on him. He came through multiple times.

He never really got into the practices with us. He was always over on the other field kicking the ball. Shula would stop every once in a while, look at him, and say, "Remember, if anything bad happens, fall on the ball." When it came to football savvy, I think Garo was very limited. When the ball bounced up into his hands (in the Super Bowl), he forgot about "fall on it" and he tried to throw it. For that, he's always remembered in that moment.

But think about the longest game against Kansas City a year earlier. (On Christmas Day 1971, Miami edged the Chiefs 27-24 in double overtime in the divisional round.) People were going down on the field left and right, because we were beating the hell out of each other. Finally, Garo comes in and kicks the winning field goal.

I've never been happier with any player than that moment with Garo Yepremian. Number one, I was glad it was over. Number two, I was glad we won. (Laughs) There were a lot of people on the other team who were just as happy it was over. It had to end. It went on for six full quarters. That's a lot of football, particularly against someone who's eyeball to eyeball with you as far as quality and stamina.

"Head On" is the title of your memoir. What does that reflect about how you've approached life?

Well, you approach life through the cards that were dealt to you.

I grew up in the farm country of Ohio. I had brothers and sisters who were much older. I had a couple of brothers and sisters who were much younger. I was kind of on my own. I grew up with nature. I had a lot of friends who lived in the woods. (Laughs) I didn't really socialize well at first at school and was kind of an outcast. You just have to meet those things head-on. That became kind of a slogan.

I was afraid of the dark when I was a tiny child. My grandmother stood me on a stool one night in the farmhouse. She was washing my hands and face before I went to bed. The other kids were in the other room watching TV with the curtains pulled. She said, "What's wrong?" I said, "I have to pee." She said, "Well, go outside and pee." I said, "I can't. It's dark. I'm afraid of the bogeyman."

She said, "Oh, no one's told you, son?" She went and shut the curtains and came over. This is my grandmother, who I thought the world of. She said it and I believed it. She whispered in my ear, "You are the bogeyman." It changed my life right there.

Little things that happen in the course of your life, you just have to adapt. You have to look at it a different way. Decide it's not going to be bad - it's going to be a good thing. You go with what happens.

What would it take for another NFL team to go undefeated?

I don't know and I hope they don't, either. (Laughs) I guard it jealously.

It's got to be more than just wanting to play, get paid, and go to the Super Bowl if we can. It's got to be a dedication that's extremely deep. The team has to be smart enough to realize that. If you've got one player or two players who go weak one time, one play in that week, it can make the difference in the game.

That is the edge: having 40 to 50 players who are that intense and that rehearsed and that serious about it. They want to win that bad.

The circumstances that we came out of - (Shula) losing a Super Bowl and coming to us, then us getting to the Super Bowl and losing it - those were all motivational factors that gave us what we needed to sacrifice. You have to sacrifice your time and make sure that you're not going through the motions. That's a big order for 17 weeks in a row.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.