Schultz: Inside the medical preparedness that saved Damar Hamlin

The well-being of Buffalo safety Damar Hamlin has been at the top of mind for the NFL, the Bills, and personnel throughout the league this week. The incident, broadcast live during Monday Night Football, shook the league to its foundation.

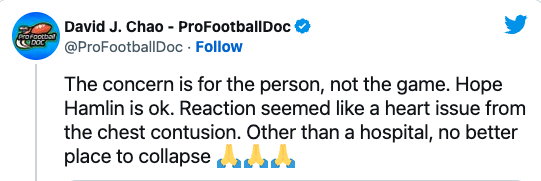

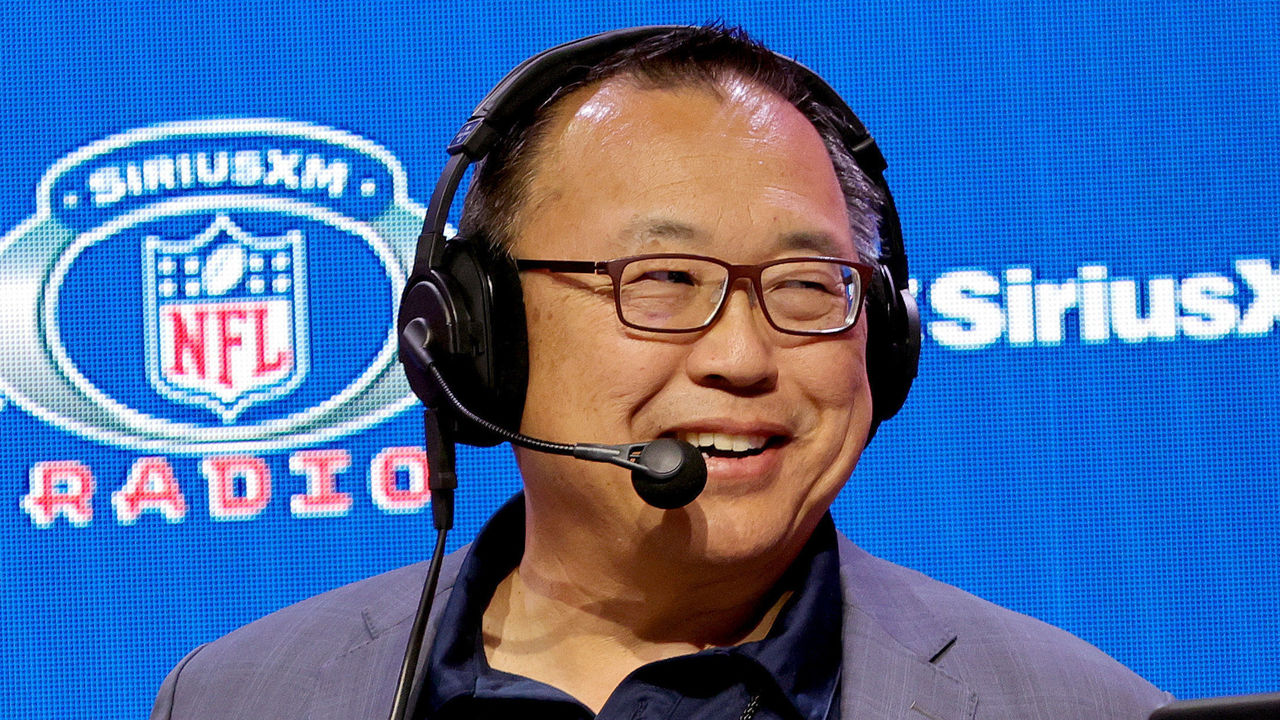

"When this happened, I tweeted basically instantaneously when I saw the replay that, let's worry about the player," said orthopedic surgeon David Chao, who was the Chargers' team doctor from 1997 to 2013. "This is his heart. But I had no idea they were doing CPR and all this other stuff.

To get some insight into how medical care is provided during games, theScore's NFL insider Jordan Schultz spoke with Chao this week. In addition to his practice, Chao now provides injury analysis at the Sports Injury Clinic website and on Twitter.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: How has on-field medical care changed since the '90s?

Chao: Well, a lot of things have changed from the '90s. I mean, heck, we didn't take concussions as seriously as we should have as an entire profession, not just the NFL. We didn't know about CTE in the '90s.

I don't know that it was the '90s, but certainly in the 2000s, we drilled an emergency action plan. And part of this whole frightening situation that I want to call everyone's attention to is that the Bills, and especially the Bengals, did a great job. Every team in the NFL drills an emergency action plan every preseason. You get the emergency doctor, the airway physician there, the paramedics there. … All the doctors, athletic trainers, everyone on the home staff get together and run a drill for cardiac and for spine. And then you put it away, and that's it.

For everyone who has criticized the NFL's concussion protocol, rightly or wrongly, they should be singing the NFL's praises for their forward thinking. For two decades-plus, teams have been preparing for this one incident that really hasn't happened. At least the cardiac side; the spine-board side happens not infrequently - had this last week in Josh Sweat, and he was discharged and he's back at the facility.

The other thing I'd say - this is clearly not just (commotio cordis). Chris Pronger had commotio cordis in 1998, I believe, during the Stanley Cup Playoffs. (Pronger returned to the ice four days later and played 13 more seasons.) This is not Damar Hamlin. Christian Eriksen, the Denmark soccer player that collapsed (with) sudden cardiac arrest and was revived and returned, is not Damar Hamlin. Damar Hamlin had some pulmonary issues, pulmonary contusion, pulmonary edema, and cardiac. Commotio cordis may be part of this, but this is not just commotio cordis.

From a medical standpoint, what about the defibrillators? When did they become available on the NFL field?

The AEDs (automated external defibrillators) have been around for over 20 years, I believe. In the NFL, each team travels with an AED device. I mean, literally, one of the athletic trainers brings it on the team bus and brings it to the team plane and brings it to a walkthrough practice when we're on the road. And just like we bring a medical bag, they bring the AED device everywhere. So, there were at least three AED devices on the field. One on the Bills' sideline, one on the Bengals' sideline, and one on the paramedic in the back of the ambulance. And that's how prepared everyone is. Medicine, (an) oxygen tank, the whole deal. I mean, like I said, unless you're physically in a hospital when you collapse and have (a) cardiac arrest, there's no better place than an NFL field.

I hope and wish the biggest thing to come out of this - Commotio cordis is most common in young male adults. Young as in Little League, young as in high school. It's actually less common as you get older in life because your chest wall gets thicker, and that's when a baseball hits you in the right spot on the chest in the right moment, or that hockey puck, or that lacrosse ball. So, what I think I would love the messaging to be coming out of it: There should be an athletic trainer and an AED device at any sporting event for youth that involves a projectile ball or any type of contact. And that device should not be locked up in the school nurse's office, it needs to be out on the field.

I am wondering if we can expand on (that) a little bit. What changes can be made, if at all, from a concussion-spotting standpoint? Can we get better at that?

Well, you know, I have sympathy for the people involved in concussion spotting because I have been there, and I (believe) that the NFL and NFLPA are trying to do the right things. But in reality, there are some things that can maybe be done, but boy, it is an impossible task. If you just take (Tua Tagovailoa)'s most recent concussion, where now everyone looks back and says he clearly hits his head. If the spotter runs down to have him checked there and he doesn't have a concussion or doesn't develop a concussion, and they don't get a first down, you have people yelling that you are affecting the game. The referee has a role in that, too, since he watches the play until the end.

If (the player) doesn't have any symptoms of a concussion, which is entirely possible since sometimes symptoms from concussions develop later, even then, you still get blamed for missing it. So, it's a very tough job. Should they maybe have even more spotters in the booth? There are three of them right now. There's (an unaffiliated neurotrauma consultant) in the booth, two (athletic trainers) and a fourth video guy who is not medical.

Yeah, that's a lot of guys.

But then again, on any given play, there are 22 guys on the field. How can your eyes stay with all 22, scan the game, and follow all of that? We're looking at it in retrospect. I didn't see it in live time, either. Because concussions are hard enough to diagnose, and because you have to rely on players reporting symptoms, and because concussions can go in different directions, what I've used over time is, this whole thing is either one degree too hot or one degree too cold. Doctors and spotters are asked to use a Goldilocks analogy: Tell me the temperature of the porridge an hour from now by just looking at it and not touching it or tasting it. I mean, come on.

What was the process of getting all these protocols in place?

There was a player - and I don't even remember his name right now - who collapsed in the locker room after a game. And this was decades ago, but that was when the league said, OK, we need to be prepared. One of the immediate changes that they made was to say that the paramedics can't leave until they check out with both head teams, no matter what. They are there until the buses roll out for the visiting teams and the locker rooms are empty.

That was one immediate change that was easy, we always had paramedics. And out of that I believe, there was a call to have trauma positions on the sidelines. And our team said trauma positions are great, but we're not cracking any chests on the sideline or in the locker room, we need emergency medicine to help run a code and/or an airway physician. That's what they are called now. That came out of that, and that has been instituted for a couple of decades. The NFL gets a lot of grief, and I can tell you from behind the scenes that they do try and do the right thing.

Doctor, this is phenomenal and very helpful.

I think there's a way to provide a medical perspective without speculating. And that's kind of our discussion here of perspective and framework without getting into what he had and the long-term effects and the specifics.

To this day, he's not out of the woods yet, but I remain cautiously optimistic. Why? Because the medical team got there so quickly. There were so many of them.

When the Bills said his heart was restarted in the field, that gave me added optimism and hope. I'm still cautious, but I think those are the things that the lay public could benefit from and know in these types of horrifying, frightening, visual situations.

Jordan Schultz is theScore's NFL insider and senior NBA reporter. Follow him on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok.

HEADLINES

- Stafford beats Maye to win MVP in closest race since 2003

- Brees, Fitzgerald headline 2026 Pro Football HOF class as Eli, Belichick miss cut

- Garrett named DPOY for 2nd time in 3 years after 23-sack season

- Vrabel wins COY over Macdonald ahead of Super Bowl LX

- Patriots legends call out Brady for not picking sides in Super Bowl LX