How alternative forms of football help the game grow

When the NCAA launches women's flag football next spring, schools will seek to duplicate the dominance of the Ottawa Braves. The university in Ottawa, Kansas, rules the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) as its four-time reigning champion.

Braves head coach Liz Sowers prizes transferable skills. Kansas is close to Arrowhead Stadium, the home turf of the NFL's dynastic Kansas City Chiefs, but there isn't an excess of high school players around the state. To construct a small-school powerhouse, Ottawa recruited athletes with two essential traits - hand-eye coordination and lateral quickness - that they'd sharpened away from the gridiron.

"You find me the best basketball players," Sowers said, "and I can arguably tell you they're some of the best flag football players."

Ottawa's success highlights a phenomenon. Thanks to an influx of new talent, football is flourishing across America in alternative forms. The spread of spinoffs that deemphasize the game's violence has created space for more players to showcase their speed, toughness, intensity, and flair.

Demand for football is fervent. A handful of colleges, including six in the 2024 season, add tackle teams annually, bringing the current nationwide count to 774. National Football Foundation chairman Archie Manning, the patriarch of American football's first family, said in a release that these programs invigorate campuses and prolong the careers of passionate high school players.

Unserved demographics - women and small guys - are getting in on the action.

In 2025, more than 30 women's varsity flag teams will populate a few NCAA conferences and the NAIA. The number of schools competing in men's sprint football - a full-contact variation with a player weight limit of 178 pounds - doubled in the past couple of years to 16.

"Why is that important? I don't know your size, but for guys like me who will never be 6-foot-5 and 240, sprint football for smaller body frames (provides) more opportunities," said Steve Hatchell, the National Football Foundation's president and CEO.

"The same with women's flag. Women's flag in high school and college is not a growth sport - it's an exploding sport."

Flag football is providing an opportunity for girls and women to #PlayFootball.

— Troy Vincent, Sr. (@TroyVincentSr) March 24, 2022

Thanks to Coach Liz Sowers and Ottawa University for showing that football is for EVERYONE 👏🏾#WomensHistoryMonth | @NFLFLAG pic.twitter.com/oiG8YjRN1V

Flag's reinterpretation of the four-down format is accessible to the masses. The NFL sponsors youth leagues in every state and combines a flag game with skills challenges to crown the winner of the retooled Pro Bowl. Novice players can take the field and deepen their understanding of the sport without being pigeonholed into a position or bowled over.

"It's a different way for young people to grab onto the sport without having to wear a helmet and pads," Hatchell said.

Football's changing shape has made it more inclusive. Frequent participation in tackle football - defined as playing it at least 26 times a year - slipped by 2.8% between 2018 and 2023, according to data from the Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA). Flag players outpace tackle players by more than a million Americans aged 6 and up, per the SFIA, since tackle is largely limited to young men.

Some women enjoy hitting, Sowers emphasized in an interview. Her own pro and international tackle playing experience helped her discover and embrace flag. The Braves benefit from expertise gleaned in the NFL by their defensive coordinator, Sowers' twin sister Katie, a trailblazing former 49ers and Chiefs assistant.

Flag rewards finesse, not brute force, but its resemblance to regular football explains the offshoot's appeal.

"Young girls are growing up watching football. Whether they're watching their brothers or their uncles or dads coach, they're seeing the game," Sowers said. "Girls want to play this game that they've never had an opportunity to play."

Sprint football's growth revived a format that Ivy League and military schools adopted to level the field for light players - the original maximum weight was 150 pounds - beginning in 1934. Sprint shares the rules and look of the standard college game, just without behemoths.

An early sprint advocate, the late Penn president Thomas Sovereign Gates, dubbed it "football for all," Philadelphia Magazine once wrote. Patriots owner Robert Kraft and U.S. President Jimmy Carter played in distant decades for historic teams - Columbia and Navy, respectively. Alumni range from George Allen, the Hall of Fame coach who got his start with Michigan's defunct sprint program, to the frat rapper Hoodie Allen, a recent Penn defensive back.

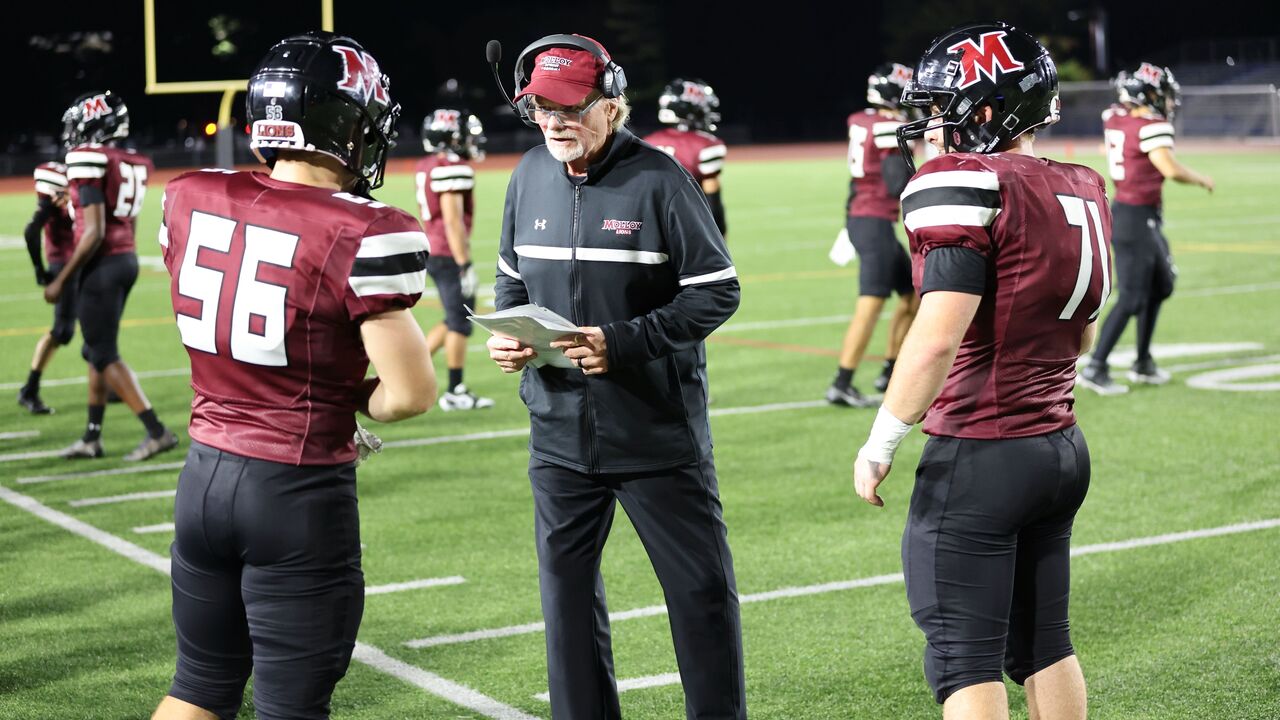

Sprint's newest entrant, the Long Island-based Molloy University Lions, went 0-7 in their 2024 inaugural season with an average margin of defeat of 46.9 points. Established powers, including league finalists Army and Navy, predictably drubbed a lineup built from scratch.

The blowouts didn't faze Brian Hughes, a lifelong local college coordinator tapped to be Molloy's head coach. He identified a recruiting wheelhouse - undersized, overlooked Division III prospects from the island - and began to actualize Molloy president James Lentini's plan for football to expand and energize the student population.

"This is a vision that he had - a way to unite the campus. Nothing gets people more excited than Friday night lights," Hughes said. "We're a Catholic nursing university first. Now we're great at business and criminal justice and education. To get another 60-75 males enrolled, regardless of their major, is also a university goal, which makes great sense."

One highlight of Molloy's first year was a 65-yard touchdown dime fired at Cornell by junior quarterback Paulie Drummond V, a Long Island native and Division III transfer. Hughes taught the fundamentals of line play to converted fullbacks and linebackers who showed they could battle in the trenches while adhering to the 178-pound limit, enforced by the league at multiple weekly weigh-ins.

A 2006 New York Times story highlighted the unique trajectories of sprint players. It noted Iraq War veterans were suiting up for Navy and a ballpark estimate of 70 doctors played for Cornell's longtime coach.

"They want to play college football, and they get a good coach and an opportunity to play against other institutions. They use what they learn to go on in life," Hatchell said. "We want you to build a house in four or five years that you're going to live in for 40. The football players of today are the leaders of tomorrow."

Elite players look forward to flag's Olympic debut. The sport's addition to the 2028 summer slate inspired NFL QBs to muse about representing the home team in Los Angeles. Darrell Doucette, the veteran face of the U.S. men's national squad, bristled at the assumption NFLers would supplant him and argued they won't have a feel for flag's shiftiness and trickery.

Today’s Wall Street Journal article referenced Darrel “Housh” Doucette, the star quarterback of the US team, as one of the best flag football players ever. Check out this clip from the 2018 AFFL Championship, where Housh made one of the greatest plays in flag football history.🏆 pic.twitter.com/reWLm1DUbh

— American Flag Football League (@FlagFootball) October 18, 2023

Sowers, who played and coached for Team USA, said the women's teams from Canada, Japan, Mexico, and Panama could seriously challenge American supremacy and underline flag's worldwide growth. Buzz about the tournament will spur youth participation. The Olympic flame is a guiding light for grassroots talent.

"It's absolutely going to motivate young girls and boys to play. More so young girls," Sowers said. "The Olympics are the highest honor in sports and a goal of everyone. It gives purpose to something they might have thought there was no future in."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- Report: Dolphins benching Tua, giving Ewers 1st start vs. Bengals

- Chiefs' Kelce: Mahomes' injury, no playoffs felt 'like it wasn't real'

- Notre Dame's Love declares for 2026 NFL Draft

- NFL Power Rankings - Week 16: Every team's unsung hero

- Fantasy: Must-add targets who can help carry you to a championship