The accidental coach: How a near-fatal injury changed Eric Wellwood's path

FLINT, Mich. - Flint Firebirds head coach Eric Wellwood gathered his players near the end of practice on a crisp November day to announce a sudden change of plans.

Practice was supposed to conclude with running stairs in the arena. But Wellwood canceled the exercise, citing his team's hard work over the previous 90 minutes. Perhaps he was also rewarding the group for capturing its first win the day before, a 7-4 triumph over the rival Sarnia Sting following an 0-16-1 start to the season.

Wellwood, 28, inherited the worst team in the Ontario Hockey League three weeks prior. As evidenced by his patchy facial hair and the fact some players know him as "Welly," he is the league's youngest head coach.

He wasn't looking for this job. A few years back, he became a coach practically by accident. And just six months ago, the former NHLer was out of hockey completely.

Yet the sport that once nearly killed him proved once again to be his life's passion. So at the close of practice, Wellwood reclined at his desk and did his best to explain how he wound up there.

"What I've realized is that you can't plan for life," he said, laughing. "And you might as well just go with it."

__________

From the time he first laced his skates as a toddler, at his backyard rink in Oldcastle, Ontario - nine miles south of Windsor - Eric Wellwood had a gift for speed.

"People would come over, literally, around the entire neighborhood, and come and just watch me skate," he said. "Like, they would want me to do circles as fast as I could because they couldn't believe how fast I was."

One of those people watching closely was Eric's older brother, Kyle, who went on to play 489 games in the NHL. He knew Eric's natural swiftness could take him a long way in hockey.

"He always had a skating stride right from a little kid that was above everybody else," said Kyle.

Eric's skating prowess led his local team, the Windsor Spitfires, to select him in the 2006 OHL Draft. Under the new ownership of former pros Bob Boughner and Warren Rychel, the Spitfires found themselves in a similar situation to today's Firebirds: losing a lot with a young team. Wellwood was part of the group who changed that.

In Wellwood's first year, Windsor finished second-last. But in 2009 and 2010, led by Taylor Hall, Ryan Ellis, and Adam Henrique, the Spitfires won back-to-back Memorial Cups. An astounding 16 players from those championship teams have since played in the NHL.

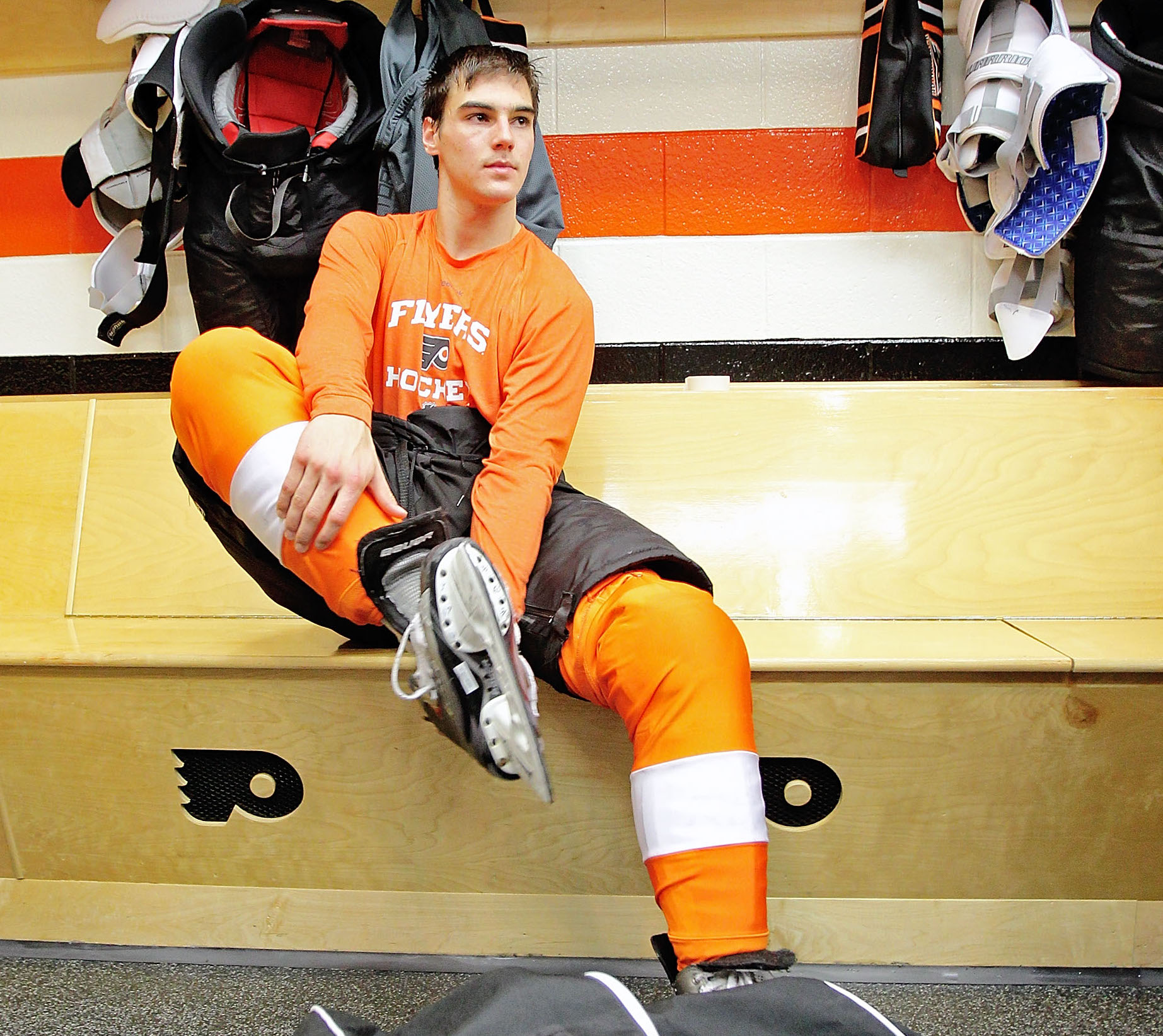

Among them was Wellwood, a long-shot sixth-rounder who debuted with the Flyers in 2010. For context, only 13 players picked after the fifth round have reached the NHL in the past five years.

"He willed his way into the NHL with his tenacious penalty killing and his speed," Rychel said.

Wellwood caught a break as a second-year pro, when the Flyers called him up for the final quarter of the regular season (and playoffs) to replace an injured player.

A lockout forced Wellwood to start the 2012-13 season with the Adirondack Phantoms, the club's AHL affiliate. He went back to Philadelphia when the NHL season began in January, struggled to produce, and was sent down after four games.

Wellwood was frustrated, but he was only 22. Sticking in the NHL takes time and the Flyers had already demonstrated a willingness to provide opportunities. This was still part of the plan.

That particular plan never came to fruition.

On April 7, 2013, a Sunday afternoon, he played his final professional game. His Phantoms lost on the road to the Bridgeport Sound Tigers - and Wellwood nearly lost his life.

Wellwood has never seen footage of the play, but it's something he'll never forget. "I could tell you everything," he said.

Bridgeport's Nino Niederreiter dragged the puck toward the blue line, put it through Wellwood's legs, and juked to the sideboards. Wellwood reacted quickly, but lost an edge and tumbled into the wall.

He was in pain. He knew something was wrong. But he didn't know how bad it was as he staggered to the bench on his own.

When he got there, his teammate Jon Sim looked down and said, "Welly, you're bleeding everywhere."

When Wellwood fell into the boards, his left skate blade cut deeply into his lower right leg, severing three tendons in his foot and 70 percent of his Achilles tendon. He'd also sliced multiple nerve endings and his posterior tibial artery. Now, blood was gushing out the top of his skate.

"Panic set in," Wellwood said.

Scary incident today. Here's to hoping Eric Wellwood and his Curt Schilling Skate recover quickly. #Phantomaniac pic.twitter.com/UjPQr3uQOk

— Danny Syvret (@DannySyvret) April 8, 2013

He was minutes from fatal blood loss. The puck was still in play when he left the bench and hobbled across the ice, where the trainer's room and ambulance waited on the other side. Phantoms trainer Greg Lowden sped out to help. Wellwood, leaving a trail of blood, could barely keep his balance.

The ride to the hospital was a blur. Wellwood felt weak from the blood loss, but his adrenaline was surging. He tried to keep his mind from wandering to a worst-case scenario.

"You had that sense that you were dying, I guess, which is an odd thing to say," he recalled. "But I just knew something was very, very wrong. And you can tell that your body is getting prepared, too."

Before undergoing two hours of surgery to tie off the artery, Wellwood spoke with his mother on the phone. She had been listening to the game online.

Days later, Wellwood underwent another surgery in Philadelphia, this one conducted by Dr. Steven Raikin, who'd previously worked on Scott Hartnell and James van Riemsdyk.

When the MRIs came back, Raikin made it clear that it wasn't just Wellwood's potential return to the ice that was at stake - there was a chance he might never walk normally again.

"Once he said that, you come to a realization that you're fighting for your normal life," Wellwood said.

The fight began with six agonizing weeks of bed rest. Most of that time, he had to keep his foot elevated, and he required assistance for simple tasks such as preparing dinner. Meanwhile, the body Wellwood had worked so hard to condition to professional quality was of no use. He was helpless - and clueless about what came next.

"You just feel horrible because you're not moving, you're not really eating, and you're on all these drugs," he said. "That was the most difficult part of the entire process."

After his cast was cut, Wellwood took his first unassisted steps on an underwater treadmill surrounded by cameras and monitors. He spent the summer of 2013 rehabbing in Philly. In August, he was back on the ice.

But he was far from ready to resume playing, so he headed home to continue rehab and skated regularly with the Spitfires. Neither the Flyers nor the Phantoms could offer him proper attention with their seasons starting.

What the Flyers did offer, however, was a rather generous extension. Wellwood's entry-level deal had expired, but the team granted him an AHL contract despite knowing he might never play again.

"They could've just said, 'Well, sorry about your luck,'" Wellwood said. "But they're a class-act organization … They essentially paid me to rehab."

As he did so, Wellwood participated in film studies and practices with the Spitfires. He also went to every game - home and away - as the team's "eye in the sky," watching from the press box and passing along observations between periods.

"It organically happened where I became a coach to them," he said. "But I was still a player."

By February 2014, Wellwood returned to Adirondack. Mentally, he was ready to attempt his comeback. Physically, he wasn't.

The reintroduction to pro-level size, speed, and skill was too much to handle. Wellwood missed half the practices in order to recover. Off the ice, he still used crutches. To compensate for the pain in his lower leg, he strained other areas of his body, creating a vicious cycle of injuries that required more treatment and caused more frustration.

After weeks of this, Wellwood visited Dr. Raikin again. The tests showed that Wellwood's current physical state was as good as it would get. And that wasn't good enough.

"I didn't want to, but sometimes you gotta look reality in the face," Wellwood said. "The next day, I called (Flyers president) Paul Holmgren and said, 'I need to meet you.' I went up and saw him and that's when I said I was gonna retire."

What now?, Wellwood thought. Hockey had been everything to him; he had no postsecondary education. The Flyers offered him a position as an off-ice assistant with the Phantoms, but he wanted more time to decide his next move. He considered firefighting in Windsor, where his mother is a captain.

And then, thanks to a casual run-in, Wellwood's plans changed again. He entered a restaurant when Windsor native D.J. Smith, then the coach of the OHL's Oshawa Generals, was walking out.

"I can remember vividly: I'm walking toward D.J., and he just yells, 'There's my new assistant coach!'" said Wellwood, who'd played for the Spitfires when Smith was an assistant coach. "And that's how it happened. That was the interview."

The job was official at the end of May. Oshawa won the Memorial Cup the following spring.

When Smith left to become an assistant with the Toronto Maple Leafs (a job he still holds), the new Generals head coach retained Wellwood. After that second season in Oshawa, another opportunity found him.

Flint Firebirds owner Rolf Nilsen fired, un-fired, and then re-fired the team's coaching staff. In response, players refused to practice. The OHL suspended Nilsen and took control of the coaching search.

Joe Birch, the league's senior director of hockey development and special events, was tasked with searching for the Firebirds' new head coach and an associate coach. Birch also happens to be D.J. Smith's first cousin. Through that relationship and Oshawa's recent success, Birch was familiar enough with Wellwood to consider him for the associate job. In the end, he didn't even interview anyone else.

Under head coach Ryan Oulahen and Wellwood, Flint reached the playoffs one year after finishing third-last. Things were looking up for the beleaguered franchise, and Birch envisioned both coaches sticking around to make sure it stayed that way.

Instead, Kyle Wellwood approached Eric with a business opportunity.

After retiring from hockey in 2014, Kyle went back to school to study business and eventually heard about HeadCheck Health, a concussion software company based in Vancouver. The two brothers decided to join the company as angel investors, and Kyle later moved into a position on the company's board.

Eric became involved with HeadCheck in the latter half of the 2016-17 season, when he was still coaching the Firebirds. In the offseason, after months of thought and many conversations with family and friends, he decided to put his full effort into the company, and eventually took on a role in business development.

The decision to step away from hockey "was not made lightly," Eric said, but it afforded him newfound freedom and flexibility in his schedule - including the opportunity to buy an RV and take a 62-day road trip across Canada with his girlfriend, Jacey Steen. They traveled over 5,000 kilometers from Windsor to Vancouver Island, hitting several provincial and national parks along the way.

Once Eric returned home, it wasn't long before his phone rang with another job offer. In April 2018, the University of Windsor men's hockey team needed to fill two assistant coaching vacancies.

Wellwood had been looking for a new venture, and though he reconsidered firefighting, he ultimately couldn't resist coaching.

"I definitely think that (he) was missing it and he wanted to get back into it," Steen said. "And then obviously he got right back into it a couple months later."

"Right back into it" means Wellwood's return to Flint in October. Oulahen stepped down after the Firebirds started 0-7, and Wellwood did not seek out the opportunity to replace him. But when Birch - again - offered him the job, Wellwood - again - couldn't pass it up.

In five years, Wellwood pinballed from New York and Philadelphia to Oshawa, then Flint, then Windsor, and finally back to Flint. He stepped out of hockey and walked back in. It hasn't always been pretty, and practically none of it has been planned, but now Wellwood is a head coach in the world's premier junior hockey league in his late 20s.

"You start looking around (for) things I'm interested in … and then you realize, you know what? Maybe hockey is what I want to do," he said. "You have a name. You built a long time to build this name. So why not continue it?"

__________

Wellwood's first act as the new head coach of the Firebirds was to take down the standings board in the locker room.

He inherited a team that started the season with 11 straight regulation losses and was allowing nearly six goals per game.

Wellwood knew several of the players because he'd been with the Firebirds two years ago, but joining a group in-season still requires a lot of catching up. He treated his first week-and-a-half like training camp, doing his best to assess the roster's strengths and weaknesses and implement his own systems.

Birch has made it clear that the team's primary goals are player development and experience. In other words, Wellwood has no pressure to quickly turn Flint into a juggernaut. That won't happen this year anyway, as the Firebirds are well behind the rest of the league (they have 10 points through 35 games; every other team has at least 21).

What matters is the feeling that Wellwood is here for the long haul to develop the Firebirds while he continues his own development as a coach.

"I think the Flint team needs some stability in their staff," Steen said. "And I think Eric knows that and he wants to be that for them."

Wellwood's eschewed stability since entering the coaching ranks a few years ago. But now, as he aims to someday coach at the NHL level, he appears to have settled in a place that can help him get there.

Then again, plans change.

HEADLINES

- Bruins' Marchand shrugs off trade speculation: 'Just fans having fun'

- Canada names Binnington starter for 4 Nations opener

- How the USNTDP's U17 crucible forged this 4 Nations team

- Why each team will, won't win the 4 Nations Face-Off

- Isles' Nelson using 4 Nations Face-Off as 'mental break' from trade talk