Concussions dominated the 2010s, but the NHL is still fighting its demons

Tim Thomas didn't expect this - the pain, the suffering, being open about both. Yet there he was, signature goatee and all, speaking candidly with a small group of reporters earlier this month in Washington.

His voice trembled. Tears streamed down his cheeks. He bore it all.

"I wake up everyday and basically have to reorder everything in my mind for the first couple hours of the day and then make a list and try to make some choices to get some stuff done," Thomas said.

The former NHL goalie feels better now than he did when he retired in 2014. But, overall, Thomas is not OK. His brain simply doesn't function like a 45-year-old's should. He says a 2015 medical scan revealed two-thirds of it was getting less than 5% blood flow while the other third was averaging about 50%. Concussions sustained between the pipes have scrambled his brain.

"I couldn't communicate with anybody for a few years," Thomas said of his early retirement days, when he'd ignore loved ones. He later mentioned he "sat out in the woods" for a while, presumably to limit contact with the world.

The decade began with such promise for Thomas, who played a starring role in Boston's 2011 Stanley Cup victory. At 36, he authored a season for Bruins lore, posting a remarkable .939 save percentage in 82 total games played, claiming both the Vezina and Conn Smythe trophies.

Thomas was in D.C. for the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame induction ceremony on Dec. 12. NHL commissioner Gary Bettman, who on several occasions has denied there's a link between hockey concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a neurodegenerative disease known as CTE, was part of the Hall's incoming class, too.

During Thomas' two-and-half-minute acceptance speech that night, Bettman was seated a few feet away, providing nods of support as the former netminder nervously stammered through some of his remarks.

The scene was surreal, all things considered, and a fitting end to the 2010s.

The concussion decade

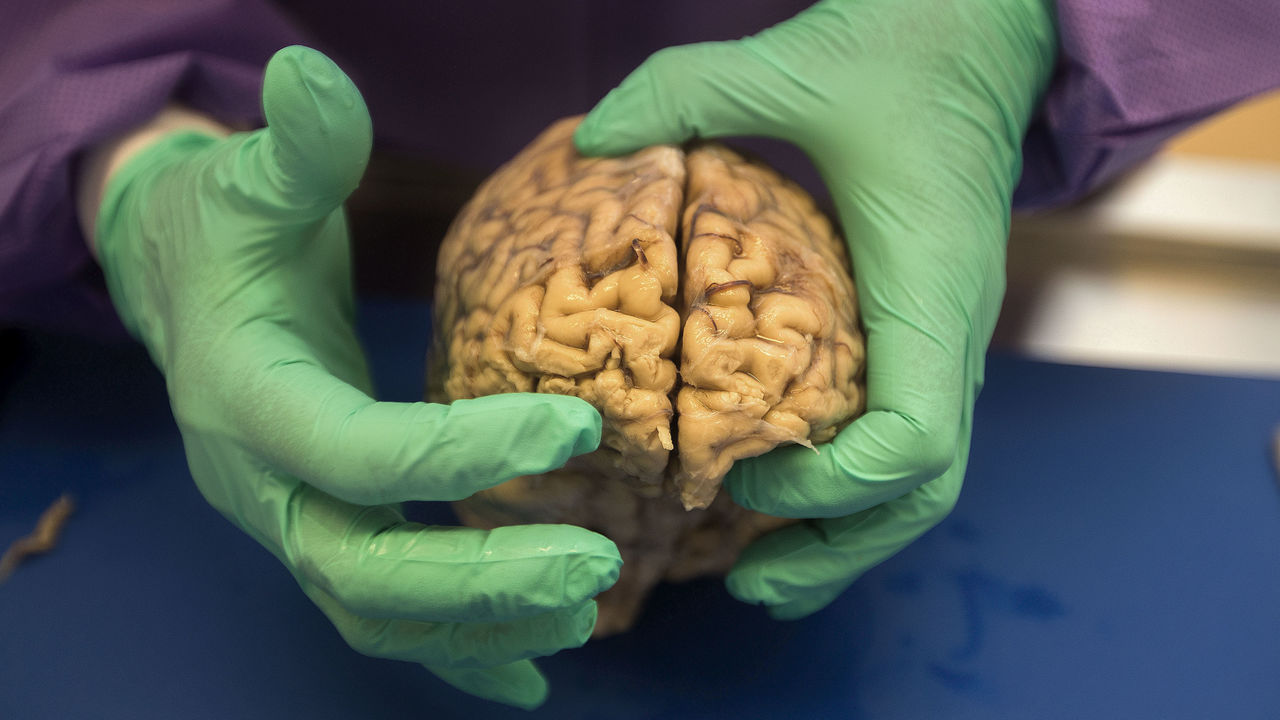

Dr. Ann McKee, a Boston University neuropathologist, made a key discovery in late 2009. Former NHLer Reggie Fleming, who died at 73 of progressive dementia, became the first hockey player diagnosed with CTE. The disease, she noted, should no longer be considered exclusive to football and boxing.

McKee's finding coincided with the NFL - the "it" league - finally acknowledging concussions can lead to long-term neurological problems. This set the tone for an enlightening past 10 years in the hockey world. "This idea of brain injuries being important in hockey has really sunk in during the last decade," University of Toronto neurosurgery professor Dr. Charles Tator said in an interview.

The issue truly hit critical mass when Sidney Crosby, the best player on the planet, took two blows to the head in the first four days of 2011. He left the Winter Classic following a blindside hit by David Steckel, and then was nailed from behind by Victor Hedman. From there, Crosby exhibited classic concussion symptoms, including headaches, balance problems, dizziness, and sensitivity to light. He battled setbacks, and didn't appear in a single game for 320 days. It was an extreme, worrisome, and very public situation.

The NHL reacted. New concussion protocol and an update to Rule 48 were introduced during Crosby's recovery period. Team physicians were authorized to send players into the "quiet room," and officials were authorized to call penalties on all hits to the head, not just some, with the ability to dish out either a minor or major penalty, not just a major.

Around this time, three former NHL enforcers were found dead over a span of four months. Derek Boogaard, 28, accidentally overdosed on medication while recovering from a concussion. Rick Rypien, 27, and Wade Belak, 35, committed suicide. Tests performed posthumously found all three had CTE. If it didn't already, the league now had a full-blown controversy to wrestle with.

In the wake of Boogaard's death, The New York Times asked Bettman about a possible link between hockey and CTE. "There isn’t a lot of data, and the experts who we talked to, who consult with us, think that it’s way premature to be drawing any conclusions at this point," he replied. Eight years later, with the list of former NHL players diagnosed with CTE reaching double digits, Bettman made a similar remark to a concussion committee in Canadian Parliament. "Other than some anecdotal evidence," he said this past May, "there has not been that conclusive link."

By the end of the decade, Bettman had ammo in the form of a legal victory. In 2013, a group of ex-NHLers filed a lawsuit against the NHL, claiming the league failed to protect its players from head injuries and didn't properly warn them of the game's health risks. The two sides settled for $18.9 million, or $22,000 for each of the 318 players involved. The 2018 payout, which included other medical help, was a fraction of the billion-dollar settlement between the NFL and a group of 20,000 former players. And, unlike the NFL, the NHL avoided liability. In a legal sense, they didn't admit any wrongdoing.

"When you have a defendant who has spent millions of dollars litigating a case for four years to prove that nothing is wrong with getting your brain bashed in, you can only get so far," NHL player attorney Stuart Davidson told the Associated Press shortly after the settlement.

In an interview with theScore earlier this month, player agent and lawyer Allan Walsh labelled the payout a "joke" that amounts to a "drop in the bucket" for the retired player community. Walsh, co-managing director for Octagon Hockey, has been one of Bettman's harshest critics, regularly taking the commissioner to task on Twitter for denying the concussion-CTE link both inside the courtroom and within the court of public opinion.

"(The denial) has huge significance, and the significance is this: Bettman is using that fallacy, that false narrative, to disclaim any responsibility for helping the players who are no longer in the NHL and who are experiencing issues," Walsh said. "It's a way of (saying), 'We are not responsible, we are not liable, and by the way, there's no association between blows to the head and CTE.'"

Walsh's passion for the issue has been fueled by difficult conversations with loved ones of former players and the players themselves. In one instance, a longtime client couldn't find his way home from a nearby market. The player, helpless and confused, couldn't connect the dots. "He didn't recognize streets," Walsh said. "He pulled over, started having a panic attack and called me and said, 'It's only two miles away and I can't find my way home, I'm lost.'"

According to Boston University, CTE symptoms include "memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, suicidality, Parkinsonism, and eventually progressive dementia." However, since CTE cannot be diagnosed in the living, doctors can only say a living player may have it. "If we don't know exactly who's got it, it's hard to start treating people," Tator, who has worked in this space for decades, said. "A lot of the treatments do carry a risk, for example, so you wouldn't want to give a drug to people you don't really know they've got CTE. Lack of ability to diagnose this in the living is really holding things up."

"There's a lot of fear out there with players who are experiencing symptoms," Walsh said of pro hockey alumni. "They're asking themselves, 'Do I have CTE? Am I going to get CTE?'"

As the 2010s moved along and investigative journalists continued to humanize the impact of concussions on former pros - TSN reporter Rick Westhead has led the charge in this area, profiling homeless ex-player Joe Murphy, among many others - a group of active NHLers hung up their skates earlier than planned. Marc Savard, Rick Nash, Clarke MacArthur, Johan Franzen, and Brenden Morrow all cited head trauma as a major reason for retirement. Ex-fighter Daniel Carcillo, who stopped playing in 2015, has been particularly outspoken about the issue, asking for accountability from the NHL.

Through it all, lawyer-speak has persisted. It became a theme of the decade, really, as various high-profile NHL figures - front-office executives, team owners, medical consultants - not only denied a conclusive link between hockey concussions and CTE through carefully worded statements, but also, in some cases, flat-out claimed while under oath during legal proceedings that they were unaware of CTE altogether.

Citing lawsuit deposition transcripts from 2015, Westhead reported Bruins owner Jeremy Jacobs was asked by a lawyer representing the players if he had ever heard of the neurodegenerative disease.

His answer? "No."

'Hockey can be saved'

To the NHL's credit, there seemed to be a shift towards better concussion awareness, prevention, and treatment in the back half of the 2010s. The concussion-spotter protocol, for instance, was updated again in 2016 to add another layer of support. There are now both in-arena spotters and centralized spotters in the league's New York office assigned to each game.

This past August, the NHL and NHLPA released a 13-minute educational video about concussion symptoms and how to identify a concussed player. Every NHLer must watch the video at training camp, according to the official concussion evaluation and management protocol. Brochures and posters are also resources for players, while medical personnel and coaches are required to attend separate concussion-related sessions at different points in the season.

Teams that do not comply with protocol guidelines - say, if a club doesn't use all the mandatory concussion-assessment tools before allowing a player to return to action - are subject to a minimum fine of $25,000. Subsequent offenses in the same season lead to "substantially increased fine amounts."

"We've put a tremendous amount of effort in diagnosing protocols, return-to-play protocols, making sure players are educated, changing the culture of the game so that players know that it's OK to say, 'I'm having symptoms,'" Bettman told reporters earlier this month at the U.S. Hockey Hall induction. "We want to make sure that we're doing everything possible, that we're staying on top of the medicine and the science as it's being told to us to make sure we're diagnosing and treating appropriately."

From Chris Nowinski's perspective as CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, the NHLPA's role in this process cannot be ignored. He says the players' union hasn't been proactive enough. "I think we are closing in on a decade since anyone from our research team had a formal meeting with anyone from the NHLPA," Nowinski said. "Considering 93% of NHL players studied (13 of 14) have had CTE, I would think they’d be more interested in understanding it, as they actually have the power to prevent it." For what it's worth, the PA donated $500,000 to concussion research in 2015.

Nowinski also hopes to see active NHL players pledge their brain for future CTE research. Only former New Jersey Devils defenseman Ben Lovejoy has made that commitment so far, when he announced his donation in late 2017. "Active players have the attention of the public in a way that retired players do not," Nowinski noted. "If they continue to choose to remain on the bench in the CTE fight, they’ll have no one to blame but themselves when there is still no treatment for CTE in 30 years, when some of them will certainly need it."

The NHL Alumni Association, meanwhile, is in the middle of a research partnership with Canopy that aims to "investigate the efficacy of cannabinoids as an integral part of a novel treatment for post-concussion neurological diseases in former NHL players." Roughly 100 ex-players are said to be participating in the randomized, double-blind study. Also, Westhead reported earlier this month that the NHLAA has established a "resource team" to support its membership, and hired a social worker.

Despite all of this, corners of the hockey world wonder if perhaps the way the game is played, promoted, and officiated needs to be recalibrated. Concussions are inevitable in all sports, since a direct blow to the head is not the only way to sustain a brain injury. "It could be just a jiggle of the brain," Tator said. "Anything that shakes the head on the shoulders can cause concussions." Logically, then, making hockey safer, at all levels, should result in fewer concussions. One way to do this is by minimizing physicality.

Hall of Famers Eric Lindros and Ken Dryden have gone on record about their shared desire to ban body contact. Lindros' career ended because of brain injuries; he's a tireless advocate for research and funding. Dryden released a biography about Steve Montador, who had CTE, in 2017; he's been a staunch Bettman opponent. The idea of no contact has its merits, but is a rather extreme idea at this point.

Walsh has a less drastic solution to propose: "I think the most sensible proposal out there - which makes absolute common sense in every way - is to actually have a ban on all hits to the head and to have the current rules that are on the books more strictly enforced," he said. "By a ban on hits to the head, that means a strict liability ban. You're not looking at intent, you're not looking at whether it's accidental. If there's a hit to the head, it's penalized."

There's hope for the future of hockey, Tator says, but only if certain rule changes pass and proper precautions are followed. "I'm not sure football will survive the ravages of brain injury. But I think hockey can be saved," he said. "There's enough prevention measures that (the hockey community) can follow to save the game."

As for Bettman and the denials, in Walsh's opinion, the clock is ticking.

"Time is working against the NHL and against Bettman," he said. "He's on the wrong side of the issue and he will ultimately be proven to be on the wrong side of history. I think his position on this issue here will be a stain on his legacy forever."

John Matisz is theScore's national hockey writer.

HEADLINES

- Slovakia takes Group B after late goal in loss to Sweden, Finland's win

- 5 key takeaways from Canada's hard-fought victory over Switzerland

- Report: Fiala to have season-ending surgery after Olympic injury

- Canada's Morrissey won't play vs. France, not ruled out of Olympics

- McDavid, MacKinnon shine in Canada's win over Swiss