Inside the wildest Stanley Cup Final ever played

Editor's note: This piece was originally published in April 2019.

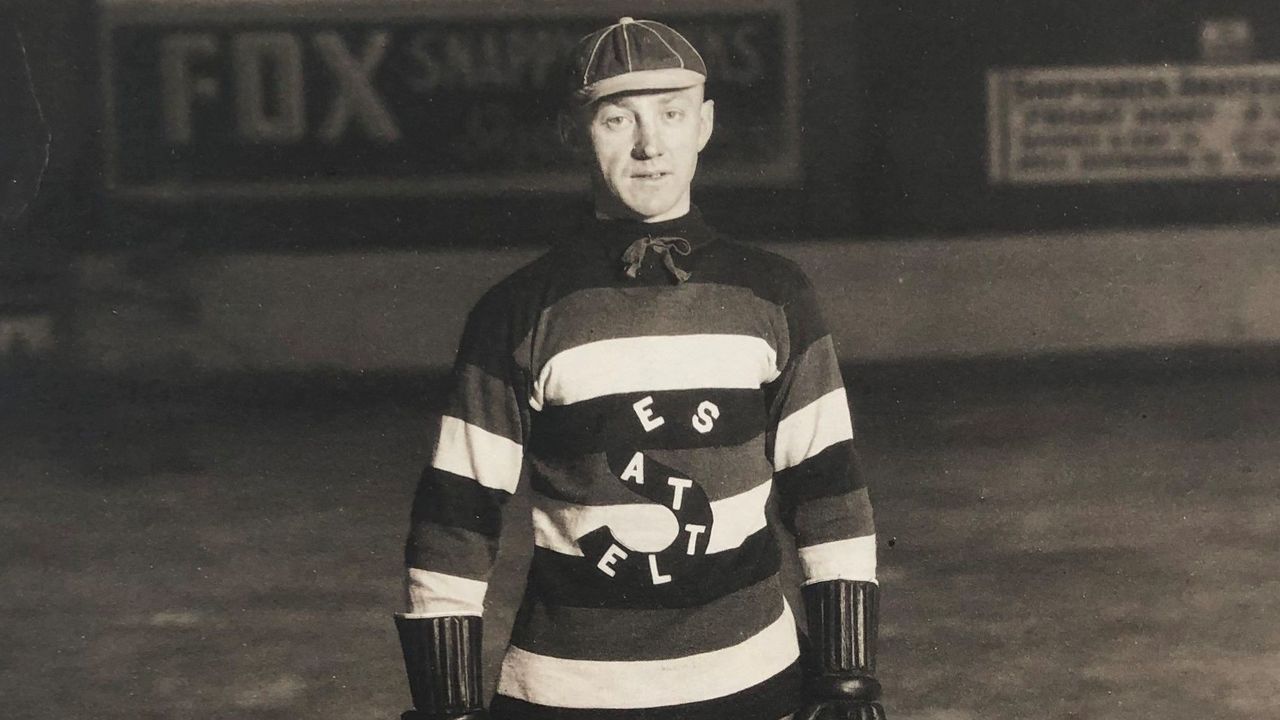

As spring bloomed in Seattle 100 years ago, Frank Foyston, the leading scorer on a team one game away from winning the Stanley Cup, received a letter from an inmate at a nearby U.S. military prison.

"Tell 'Happy' to board up the old tent, everybody shoot hard, and the Mets will cop the old championship," the note read.

Foyston's correspondent was a 28-year-old Canadian named Bernie Morris who'd been clinging for weeks to the hope that he, too, would get the chance to play in hockey's title series. Two years earlier, Morris had starred at center for the Seattle Metropolitans in the Stanley Cup Final. He scored 14 goals in four games as his squad rolled by the mighty Montreal Canadiens and became the first American franchise to win the trophy in the 25 years it had been awarded.

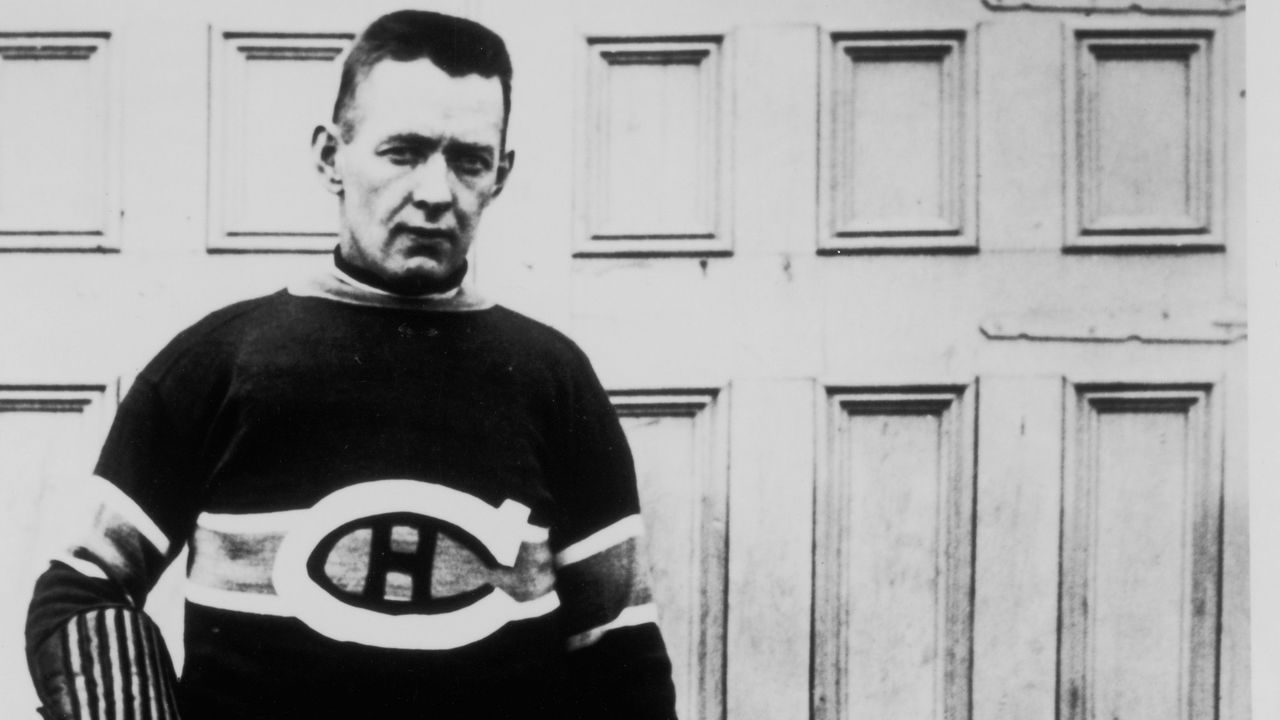

Had Morris been in the Metropolitans' lineup in March 1919, when they faced the Canadiens in a slightly belated rematch, his prediction that Seattle would soon fete another champion might have been regarded as obvious. Three of his Mets teammates were future Hall of Famers, including Foyston and goaltender Hap (or "Happy") Holmes. And by virtue of vying for the Cup in an odd-numbered year, Seattle got to host the whole best-of-five series, a quirk of the sport's scheduling patterns at the time.

But as the Canadiens journeyed across the continent by railcar, intent on securing redemption after their trouncing in 1917, Morris found himself stuck in Camp Lewis - a U.S. Army base where newly mobilized soldiers had been trained to fight in World War I, and where he now sat confined on a charge of dodging the draft.

"Morris … writes that he is with the team in spirit if not in person," the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper reported at the time, summarizing the rest of his message to Foyston.

More than any other playoff held so long ago, people remember the 1919 Stanley Cup Final because of the calamitous circumstances that brought it to an early end. A historically deadly influenza pandemic thwarted the proceedings before a champion could be crowned; the deciding game was canceled when five Montreal players were bedridden with the flu. One of them, rugged defenseman Joe Hall, died from the effects of the illness at the age of 37. "SERIES NOT COMPLETED" was eventually carved into the Cup.

But fewer people remember the extraordinary chain of events that led to the final's cancellation. It might be the wildest hockey series ever staged, not least because one of its principal characters spent it desperately, and unsuccessfully, trying to avoid being shipped to Alcatraz.

Frank Patrick, the president of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, had never witnessed a stranger combination of scenes. On April 1, 1919, the day the last game was called off, he said the final had been "the most peculiar series in the history of the sport."

In the first week of March 1919, when U.S. military officials apprehended Morris in Seattle, they let him play one game before they took him into custody: the last matchup of the Metropolitans' PCHA regular season. After Seattle beat the visiting Victoria Aristocrats 3-1, he was whisked away to plead his case.

Morris, a Manitoba native who lived in Seattle during the three-month PCHA season and worked at a remote site in the British Columbia woods for most of the year, had won an exemption from the U.S. draft - until, that is, his status changed and he was conscripted for service Nov. 5, 1918, six days before the end of the war.

Living so far off the grid at the time he was drafted, Morris contended that he'd never been notified of his call to duty. He and Seattle coach Pete Muldoon figured it wouldn't take long for the misunderstanding to be clarified. The shorthanded Metropolitans didn't stumble in the meantime: A week after his arrest, they outscored the Vancouver Millionaires 7-5 in a two-leg playoff to win the PCHA title.

Seattle's reward was a best-of-five showdown for the Stanley Cup with the Canadiens, who'd bested the Ottawa Senators to clinch the NHL championship. The 1918-19 season, the NHL's second in existence, had been rocky. The nascent league's only other team, the Toronto Arenas, had folded suddenly in February with two games left on the schedule. A couple of months before the season began, Ottawa player Hamby Shore had succumbed to pneumonia brought on by the influenza virus.

The Canadiens hoped to finish the year on a high note. To accomplish that feat on the road against steep odds, they would rely on their own stars. Legendary player-coach Newsy Lalonde had fileted Ottawa for 11 goals in five games in the NHL final. Didier Pitre was a potent scorer who went on to make the Hall of Fame. In goal was beloved veteran Georges Vezina, whose netminding prowess later inspired the namesake award after his death at 39 from tuberculosis. All three players were party to Seattle's resounding Cup victory in 1917.

"The crack Eastern team felt keenly their beating at the hands of the Seattle men several seasons ago," Post-Intelligencer reporter Royal Brougham wrote in a series preview on March 16, 1919, "and a few days ago (Canadiens manager George Kennedy) sent word ahead that he hoped Seattle would win the playoff, as his players were praying for another crack at the Mets."

Game 1, held at Seattle Ice Arena on March 19, proved a rude reawakening: The Metropolitans dusted Montreal 7-0 on the strength of a Foyston hat trick. Kennedy had praised the Mets' speed on the eve of the series, and Seattle's forwards, true to form, had broken through for umpteen clear shots on Vezina. The Canadiens seemed flummoxed by the PCHA rules under which the game was played, namely the fact each team iced a sixth skater - a rover - and was permitted to pass the puck forward in the neutral zone.

| Game 1 | Goals | Scorers |

|---|---|---|

| Seattle | 7 | Frank Foyston (3); Muzz Murray (2); Jack Walker; Ran McDonald |

| Montreal | 0 |

A few days later, Kennedy offered two novel excuses for his team's struggles: they were bothered by Seattle's "warm climate," with temperatures exceeding 50 F (10 C) during the day, and they weren't accustomed to walking on "cement sidewalks" in late March, as opposed to Montreal's soft, snow-covered walkways.

Nevertheless, the Canadiens evened the series with a 4-2 win played under NHL rules. Lalonde netted the first four goals of Game 2, upping his total for the postseason to 15, and Montreal withstood a stirring sequence midway through the third period in which Seattle scored twice within eight seconds.

| Game 2 | Goals | Scorers |

|---|---|---|

| Montreal | 4 | Newsy Lalonde (4) |

| Seattle | 2 | Bobby Rowe; Frank Foyston |

As Kennedy bemoaned the off-ice conditions, the Mets learned after Game 2 that Morris would be detained at Camp Lewis for several more weeks, ruling him out of the series. Their disappointment was tempered when Foyston, with Game 3 operating under PCHA rules, recorded a first-period hat trick and later beat Vezina for a fourth goal in a 7-2 Seattle victory. (Postgame, the Canadiens got dismal news of a different kind: an amphitheater where Kennedy promoted wrestling matches had burned to the ground in Montreal.)

| Game 3 | Goals | Scorers |

|---|---|---|

| Seattle | 7 | Frank Foyston (4); Cully Wilson; Muzz Murray; Roy Rickey |

| Montreal | 2 | Odie Cleghorn; Louis Berlinguette |

The absence of Morris, whose letter was delivered to Foyston after Game 3, meant Muldoon had only seven skaters at his disposal. The Mets never confronted a greater test of their stamina and willpower than Game 4 - "the hardest-played game in hockey history," Patrick said after the final whistle.

After combining for 22 goals through the first three games, neither team scored on the night of March 26. The brilliance of Vezina and Holmes forced the game to overtime. The run of play was even, and the pace unrelenting. Hall high-sticked Seattle forward Jack Walker for three stitches above his eye. Seattle thought it had scored at one point in regulation time, but the period had ended a second earlier. Mets enforcer Cully Wilson came within a hair of a game-winner early in OT; Lalonde almost ended matters for Montreal moments later.

"What a difference your leading scorer would have made in a tie game," Kevin Ticen, the author of a new book about the Metropolitans, told theScore in reference to Morris.

| Game 4 | Goals | Scorers |

|---|---|---|

| Seattle | 0 | |

| Montreal | 0 |

The contest ended without resolution after 80 minutes, at which point several exhausted players promptly keeled to the ice. Wilson had nearly fainted with a few minutes left on the clock. The following day, Seattle commissioned an osteopath to care for a severe strain in Foyston's thigh. Several of his teammates stayed in bed until well into the afternoon.

As the weary recuperated, officials decreed that Game 5 would be played under NHL rules, in effect serving as a replay of Game 4 - and that no Stanley Cup game would ever finish in a tie again.

The condition of Foyston's leg had improved by March 29, and when Seattle took a 3-0 lead into the second intermission of Game 5, it appeared his team's fleetness of foot would nullify any rules advantage Montreal should have enjoyed. But in the third period the Mets' fitness failed them, and the Canadiens, skating furiously, rallied to make it 3-3 on an Odie Cleghorn goal and two remarkable solo efforts from Lalonde.

Fifteen minutes into overtime, as Foyston lay flat on the Seattle bench after aggravating his thigh, one of Walker's skates broke and Wilson, utterly drained, chose that moment to beckon for a substitute. Before he could be replaced, one of Montreal's reserve forwards, Jack McDonald, gained possession of the puck, circumnavigated the Seattle defense, and scored the goal that tied the series.

| Game 5 | Goals | Scorers |

|---|---|---|

| Montreal | 4 | Newsy Lalonde (2); Odie Cleghorn; Jack McDonald |

| Seattle | 3 | Jack Walker (2); Frank Foyston |

Kennedy, who'd sent McDonald onto the ice amid the confusion in the Mets' ranks, was all smiles as he spoke to reporters. His team had erased its three-goal deficit without Hall, who'd become sluggish and left for the dressing room in the second period. Now one game remained to settle the title.

"I always claimed I had a game team, and the boys certainly proved it tonight," Kennedy said. "I expect them to win the championship now."

Kennedy and his club never got the chance. By the end of Game 5, the misery the series inflicted on all of its participants was plainly evident. Doctors determined that Foyston had torn a tendon. Seattle blue-liner Roy Rickey was 10 pounds lighter after playing 155 consecutive minutes over two overtime-prolonged games. His defense partner, Bobby Rowe, could barely stand on his bum ankle, the result of a hack from Hall several nights earlier.

The Canadiens' plight was cause for greater concern. Hall and McDonald awoke with high fevers the morning after Game 5. Kennedy, Lalonde, defenseman Billy Coutu, and left winger Louis Berlinguette were all confined to bed at Seattle's Georgian Hotel with illnesses of their own. By April 1, the day of Game 6, Hall and McDonald had to be rushed to hospital.

Even in his sickly state, Kennedy was set on icing a team for the conclusive game. He suggested he could wrangle reinforcements from the Victoria Aristocrats, Seattle's lowly PCHA opponent. Muldoon rejected the offer on the Mets' behalf, and Patrick insisted that he wouldn't compel Montreal to forfeit the Cup.

The circumstances, Patrick said, dictated that Game 6 couldn't be played that night or anytime soon. At noon on April 1, seven hours before puck drop, arena staff started removing the ice surface to make way for a summer roller rink, and by 2:30 p.m., officials confirmed what was already clear: The series was over.

"Not in the history of the Stanley Cup series has the world’s hockey championship been so beset with hard luck as this one has," read a dispatch in the Montreal Gazette and other newspapers on April 2, 1919.

"The great overtime games of the series have taxed the vitality of the players to such an extent that they are in poor condition indeed to fight off such a disease as influenza."

The observation was tragically prophetic. From 1918-20, the influenza strain that felled the Montrealers infected one-third of the global population and killed an estimated 50 million to 100 million people. Hockey historian Eric Zweig, whose children's novel "Fever Season" is based on the 1919 Cup final, said the pandemic could strike at terrifying speed: "You could be healthy when you went to bed, wake up in the morning feeling sick, be really sick by lunchtime, and be dead by dinnertime."

Reports of Hall's condition grew increasingly dire. On April 2, his fever was said to have reached 103 F (39.4 C). The next day, he contracted pneumonia. By April 4, each ailing Canadiens player was feeling better, except for him. He died at 2:30 p.m. on April 5.

Newspaper obituaries recounted his life story to mournful readers. Hall was born in England in 1881 and grew up in Brandon, Manitoba. He won Stanley Cups with the Quebec Bulldogs in 1912 and 1913 and joined the Canadiens in 1917. "Hall was a star of the first magnitude when many of the young players on his team were infants," the Post-Intelligencer wrote. The Toronto World called his two-decade career "long and checkered," but noted that despite his trademark aggression, he made friends wherever he played.

"I cannot tell you how deeply grieved I am to hear of Hall's death," said Frank Patrick's brother, Lester, whose long playing career ran parallel to Hall's. "Joe had a heart as big as a house and was a prince of good fellows."

Hall was buried in Vancouver on April 8 in the presence of his wife, Mary, and their three children. Lalonde and Berlinguette served as pallbearers, as did Lester Patrick. Lalonde departed on the long ride back to Montreal a few days later - but only after telling reporters that, had the last game of the final been played, the return to PCHA rules would have guaranteed Seattle the Cup.

The Metropolitans dispersed for the offseason. Wilson had accepted a job at Seattle's shipyards as soon as the series ended, while Walker undertook the same work back home in Ontario. Foyston, still hobbling on his injured leg, got married on the day after Hall's funeral with Holmes serving as best man. That summer, the Post-Intelligencer reported, the forward and the netminder planned to run a wheat ranch together.

A week after Hall's death, army officials at Camp Lewis decided where Bernie Morris would spend the offseason: the military prison on Alcatraz Island. Seattle's erstwhile star scorer was sentenced to two years of hard labor for desertion, a verdict Frank Patrick vowed he would help contest, if need be, all the way to the desk of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

In the end, Morris was imprisoned for a year before he was exonerated and released - just in time to suit up on the road against NHL champion Ottawa in the 1920 Stanley Cup Final. Rendered rusty by his lockup, Morris only contributed two assists all series, but Foyston scored six goals as the Mets won two of the first four games and pushed the Senators to a winner-take-all matchup for the title.

Seattle lost that game 6-1. Vancouver defeated the Mets in three of the next four PCHA finals, and the franchise folded in 1924, ensuring they'd never play for the Cup again.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.