The dazzling, forgotten hockey hero who rejected the NHL

Francis Xavier Goheen's chest wasn't really the size of a house, and it's hard to believe each of his thighs was as thick as a slighter man's waist. But Tony Conroy, his teammate in the 1910s, figured there's fun to be had in hyperbolizing, and hints of truth to be found in the comparisons, too. Goheen was maximally strong for his 172 pounds. Out went his given names, replaced by a nickname destined to stick: Moose.

"It wasn't just Goheen's size that impressed Conroy," hockey historian Alan Livingstone MacLeod wrote many years later. "He rhapsodized about Moose's remarkable speed and competitiveness, too."

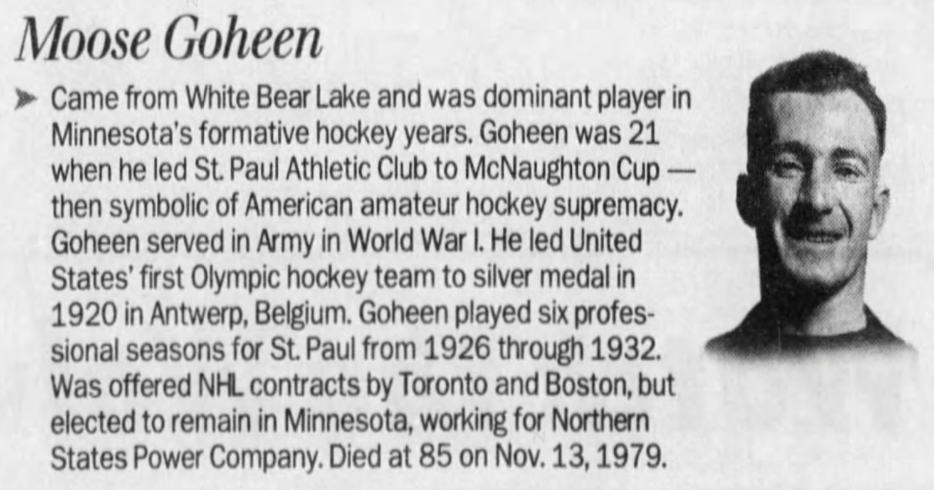

Moose Goheen was one of the best hockey players of his era, a distinction that endures without most people knowing it today. He was a defenseman from Minnesota, the "State of Hockey," a claim founded on the back of the national amateur titles his squads won around the time of World War I. He served in Belgium during that period, then medaled there when hockey made its Olympic debut at the 1920 Games.

The Boston Bruins and Toronto St. Pats (soon to be the Maple Leafs) craved his physicality and scoring punch. But Goheen declined contract offers at every turn, preferring to play at home in St. Paul - and to keep working all the while at the local power company.

That Goheen never suited up even in the embryonic NHL ensured history would overlook his feats. Roger Godin, another historian and author, lamented that fact in a book about Goheen's St. Paul teams. Sports Illustrated omitted Goheen from a list of Minnesota's 50 greatest athletes, Godin noted; a Twin Cities newspaper rated him 59th in a similar exercise. Those affronts wouldn't have flown in Goheen's day, when keen observers considered him the spitting image of Eddie Shore, the legendary hard-nosed Bruin.

Hobey Baker was the only American player to precede Goheen for induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame. When pioneering defenseman, coach, and team executive Lester Patrick called Goheen the best player the U.S. produced, his endorsement still fell short of the highest praise Moose received. A few years after he shone at the Olympics, the St. Paul Pioneer Press conferred him another towering title: "The Babe Ruth of American hockey."

Hockey's Babe excelled in baseball and football too as a kid in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, at the turn of the 20th century. Yet when Goheen reached young adulthood, his flair on the ice pushed him a few miles south to St. Paul, where his hockey career began at the elite amateur level with the St. Paul Athletic Club. Moose and the AC's won three national championships before and immediately following the U.S.'s engagement in the war, establishing a throughline of Minnesotan devotion to the game that later enabled the creation of the NHL's North Stars and Wild.

"The State of Hockey began with these men," Godin wrote in "Before the Stars," his 2005 book about Goheen and the AC's.

Happy 126th birthday today posthumously to former @HockeyHallFame defenseman - Francis Xavier 'Moose' Goheen born in White Bear Lake, MN. Goheen was often regarded as the Gretzky of his era, playing professional hockey with the St. Paul Athletic Club pic.twitter.com/kyG4KxczM7

— Vintage MN Hockey (@VintageMNHockey) February 10, 2020

Nominally a defenseman, Goheen had the ability, build, and drive to play any position, from rover - back when teams iced seven players a side - to a single reported appearance in goal. But he was at his best on the blue line. From there, he spearheaded dazzling end-to-end rushes several decades before Bobby Orr popularized the act. Minnesota sportswriter Halsey Hall opined in print that no spectacle in sports "could ever beat the sight of Moose Goheen taking the puck, circling behind his own net, and then taking off down that rink, leaping over sticks along the way."

"His body was just like a rock," Bev Goheen, Moose's daughter-in-law, once told the author Seamus O'Coughlin. "When he came straight down center ice, he was going through no matter who was there. He had one thing in mind and that was to get the puck in the net."

Then as now, gaining possession to try to score meant displacing opponents from the disc. Goheen endeared himself to the home faithful - and galled countless onlookers outside of St. Paul - with his affinity for crunching checks. Late in his career, word surfaced in newspapers that he and Shore had separately challenged Art Shires, a major-league first baseman who moonlighted for a time in boxing, to a bout.

That isn't to say Goheen had to stray from his usual domain to stoke conflict, as exemplified by Hall's memory of a road game in which Goheen broke the wrist of an opposing star.

"The town was furious. It thirsted for Goheen's blood, promising danger to his existence if he played the next night in the two-game series," Hall later wrote. Against his coach's wishes, Goheen insisted that he dress and brave whatever wrath awaited him.

"The players ganged on him. The fans grabbed at him as he roared along the boards," Hall continued. "And, to nobody's particular surprise but to their overwhelming admiration, the star of the game was Moose Goheen."

While the likes of Shore and Patrick competed for and lifted Stanley Cups, the self-avowed pinnacle of Goheen's hockey life was the 1920 Olympic tournament in Belgium, where two years earlier the U.S. Army Signal Corps had tasked him with laying telephone wire over reclaimed battlefield terrain. Those Summer Olympics were held in Antwerp to boost depleted Belgian spirits in the wake of the war. 1920 marked hockey's introduction to the Olympics, and the occasion called for Goheen to return to the country in a different kind of American uniform.

To maintain the ice at Antwerp's Palais de Glace, the seven-team hockey bracket took place in April, several months before the rest of the games, though puck drop was postponed a few days because of the Americans' late arrival by ship. Goheen, three St. Paul teammates, and the rest of the U.S. squad were saluted by a crowd when they docked, and the schedule delay didn't deter them from racing to a 29-0 win over Switzerland, whose 46-year-old winger Max Sillig was elected president of the IIHF midway through the tournament.

Sillig's inclusion on the Swiss roster at his age was hardly the most extreme thing about the event. Each game lasted 40 minutes, split into two periods, which still was ample time for lopsided scores to proliferate. The knockout format of the day eliminated the host Belgians and France after one game apiece, each a shutout loss to Sweden. The Winnipeg Falcons, the senior amateur club that represented Canada, thumped Czechoslovakia 15-0 and the Swedes 12-1, but the hard-fought win that effectively sealed the gold medal came in between, a 2-0 victory over the Americans.

Losing to Canada still afforded the U.S. a shot at silver, which they clinched by blanking Sweden 7-0 and Czechoslovakia 16-0 on consecutive days. (The lone goal Czechoslovakia managed to score in Antwerp was timely, coming in a 1-0 win over Sweden for bronze.) North American speed and skill had triumphed in Europe, and St. Paul's contingent got to sail home as lauded men. Goheen, the anchor of the back end, scored seven goals - six against the Swiss - and electrified the Palais de Glace with his splendid signature rushes.

After Antwerp, Goheen's career split into two phases: his continued time as an amateur and his jump to the pros, with the St. Paul Saints in 1925. He played a season in the ill-fated Central Hockey League and several in the American Hockey Association, a minor circuit with three Minnesota teams and others as far as Winnipeg, Detroit, and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Through it all, he kept a day job at Northern States Power - the utility, by coincidence, whose successor company Xcel Energy now sponsors the NHL Wild's arena.

| Pro career | Goheen's team | League | GP | G | A | PTS | PIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925-26 | St. Paul Saints | CHL | 36 | 13 | 10 | 23 | 87 |

| 1926-27 | St. Paul Saints | AHA | 27 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 40 |

| 1927-28 | St. Paul Saints | AHA | 39 | 19 | 5 | 24 | 96 |

| 1928-29 | St. Paul Saints | AHA | 28 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 39 |

| 1929-30 | St. Paul Saints | AHA | 36 | 9 | 8 | 17 | 47 |

| 1930-31 | Buffalo Americans | AHA | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

(Source: HockeyDB)

Goheen enjoyed his work, which was steady and paid well, and he used this logic to justify rejecting the NHL's frequent - and, for the period, lucrative - overtures. The Montreal Wanderers wanted to sign Goheen in 1917, the NHL's inaugural season, according to O'Coughlin, the author. A two-year offer worth $4,000 annually failed to convince him to join Toronto in 1925. The Bruins attempted to bring him aboard at the outset of 1928-29. Boston won the franchise's first Cup that March, but without Goheen, whose reported $12,000-a-year salary request proved too steep.

So resolute was Goheen's allegiance to his home state and to Northern States that he turned down the chance to play for the U.S. at the first Winter Olympics, at Chamonix, France, in 1924. Speaking to O'Coughlin many years later, Goheen's daughter-in-law connected his thinking to the conditions of his upbringing in White Bear Lake. Goheen grew up poor, she said, and he grew accustomed to retrieving coal chunks from the side of nearby train tracks to heat his childhood home. The adult Moose played with abandon between the boards, but away from the rink he shied from what he perceived to be undue risk.

"Moose's big thing was security," Bev Goheen said. "That had everything to do with the decisions he made in his life. When he got his job at Northern States Power, that paycheck meant everything to him."

Rather than teaming with marvelous St. Pats center Jack Adams or celebrating Boston's title with Shore, sticking in St. Paul made Goheen a hometown hero - and persona non grata in rival Minneapolis. Hostile away crowds always seemed to invigorate Goheen, one St. Paul news report waxed in 1923: "He plays such a hard game and causes so many spills that there is ample chance for fandom's ire." Yet when he retired and began to try his hand at officiating, Goheen proved supremely and surprisingly popular in the neighboring Twin City.

"Possibly because he has had plenty of chances to study hockey officials, Frank is our idea of what a good one really is," Minneapolis Star columnist Charles Johnson wrote in 1931. "He moves up and down the sideboards without most of the crowd seeing him, and he doesn't miss a thing. He steps into the spotlight only when absolutely necessary."

Old-timers from Goheen's generation went to the wall to defend him. They would have been joyed to see him inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame on Aug. 18, 1952, as part of the nascent museum's fifth class - and aggrieved had they come across Jack De Long's reaction column in the Vancouver Sun, in which De Long objected to the enshrinement of an amateur who hadn't played an NHL game.

Within a few days, De Long reported to his readers that he'd "just made contact (violent) with the Loyal Order of the Moose (Goheen) Society," members of which phoned him in droves to vouch for the defenseman's credentials. The GM of a local minor pro franchise said Goheen was a "swell fellow," and therefore Hall-worthy. One of De Long's friends was said to have presented a sounder argument: Goheen was the Babe Ruth of U.S. hockey.

The recognition Goheen received during and after his lifetime - he died at 85 in 1979 - could never compare to that of the Babe, but his legacy is watertight. He was the second American to enter the Hall after Baker, a charter inductee who starred in college at Princeton in the early 1910s. Baker never turned pro, and died mysteriously in France shortly after World War I ended. In his book on Goheen's St. Paul teams, Godin mused about the partnership they could hypothetically have formed: the lithe Baker acting as his decade's Wayne Gretzky, Goheen the equivalent of Mark Messier.

Goheen was elected to the Hall the very same year as one Ernie "Moose" Johnson, a fine two-way defenseman on west-coast teams in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, whose champions used to play for the Stanley Cup. The timing was apt, Goheen hinted in a speech in 1958, when he saw fit to reveal another layer of his story.

"I was never a moose, either, at 172 pounds," Goheen said, reflecting on his earliest years in the senior amateur ranks in St. Paul. "But Tony Conroy named me after Moose Johnson of Portland."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.