Why is the modern power play so effective?

Toward the end of a five-on-four power play Monday, Golden Knights defenseman Alex Pietrangelo curled behind his own net, gathered the puck, and skated out of the zone unbothered. With no opposing players applying pressure, Pietrangelo gently left the puck for a trailing teammate, Alex Tuch.

Tuch galloped through the middle of the ice before dishing the puck to William Karlsson for a smooth zone entry, and Karlsson shielded the puck until he could safely pull off a nifty backhand pass to Reilly Smith.

At the hash marks, Smith turned to face the net. He then sent the puck cross-ice, through a defender's legs, to Alec Martinez, who unleashed a wrist shot. The puck hit the top corner, short side, capping off a gorgeous sequence:

Goals, goals and MORE GOALS! 🚨

— NHL on NBC Sports (@NHLonNBCSports) May 4, 2021

Alec Martinez converts on the power play. #VegasBorn pic.twitter.com/wwBTyuL83f

That goal, Vegas' second in a 6-5 loss to the Wild, was one of those rare occasions where the Xs and Os relayed in a power-play meeting come to fruition - flawless entry, efficient puck movement, decisive shot.

It was also par for the course in today's NHL.

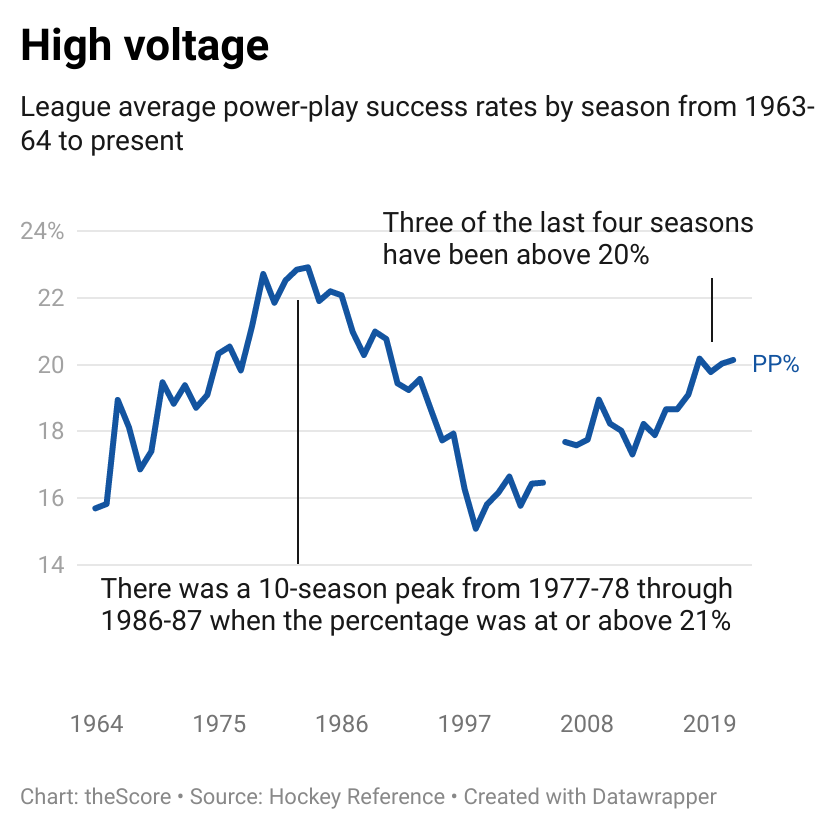

In this truncated regular season, power plays have been highly proficient. With 53 total games left, the league-wide power-play success rate is 20.11%.

The NHL began tracking PP% in 1963-64. Since then, only 18 seasons featured a league-average success rate of 20% or higher. The first 15 of those 18 seasons took place in the high-octane 1970s and '80s. The other three? This year, last year, and 2017-18. And power plays in 2018-19 and 2016-17 weren't far behind, clicking at 19.78% and 19.10%, respectively. (For reference, not a single season from 1993-94 to 2015-16 eclipsed 19%.)

The metric 5-on-4 goals for per 60 minutes measures power-play excellence more accurately than PP% by excluding five-on-threes and accounting for the duration of each power-play opportunity. Per Evolving Hockey, the past five seasons rank first (2017-18), second (2020-21), third (2019-20), fourth (2018-19), and tied for fifth (2016-17) in 5-on-4 GF/60 among the 14 seasons tracked.

So why has the modern power play produced such impressive numbers over the past five seasons?

The NHL was established more than a century ago, so virtually every power-play configuration and formation have been rolled out at some point in time. What's unique about the 2021 landscape is the near-universal adoption of one particular configuration - four forwards and one defenseman - and one particular formation: 1-3-1.

Coaches have taken the NHL's "copycat league" label to its logical extreme, as it's become increasingly rare to see multiple defensemen share the ice on the power play. In fact, according to the fantasy hockey website Daily Faceoff, the Coyotes and Sharks are the only clubs still using the three forward-two defenseman configuration with their first unit.

The same trend line applies to the ubiquitous 1-3-1 formation, where, inside the attacking zone, the defenseman quarterbacks the power play from the point. A "flank" on each side and a centrally located "bumper" guy occupy the middle level, and the unit's fifth member inhabits the messy netfront area.

"The D-men now are what impress me the most about today's power plays," Hockey Hall of Fame forward Dave Andreychuk, who bagged an NHL-record 274 power-play goals from 1982 to 2006, said in a recent interview.

"The D that has mobility at the top of the (penalty-killing) box, that can move around freely and handle the puck responsibly, I mean, that's a necessity now to have a good power play."

The NHL's love affair with the 4F-1D and 1-3-1 probably wouldn't have materialized - and league-wide power play rates probably wouldn't eclipse 20% - without the defenseman position undergoing a significant change in priorities and skill set over the past decade. The new-age blue-liner is incredibly agile and boasts a high tolerance for risk, traits that align perfectly with the favored power-play strategy.

Jeff Ulmer, a former longtime professional forward who worked in player development for the Coyotes from 2018-20, notes that teams like the Rangers and Avalanche essentially ice five-forward units. Young defensemen Adam Fox and Cale Makar can skate and handle the puck as well as any center or winger in the league, and their role in the 1-3-1 - that of a QB at the point - encourages creativity.

"Cale Makar walking the blue line is already dangerous," Ulmer said of Colorado's point-per-game playmaker. "Then you've got a guy on each flank taking shots. There's all these different variants now to defend against."

He added: "I don't think the point shot is going the way of the dinosaur, but I think teams are recognizing that the more shots you can get from closer to the net, the better. The flanks, the netfront guy, and even the bumper guy, who can move up and down, all offer that option."

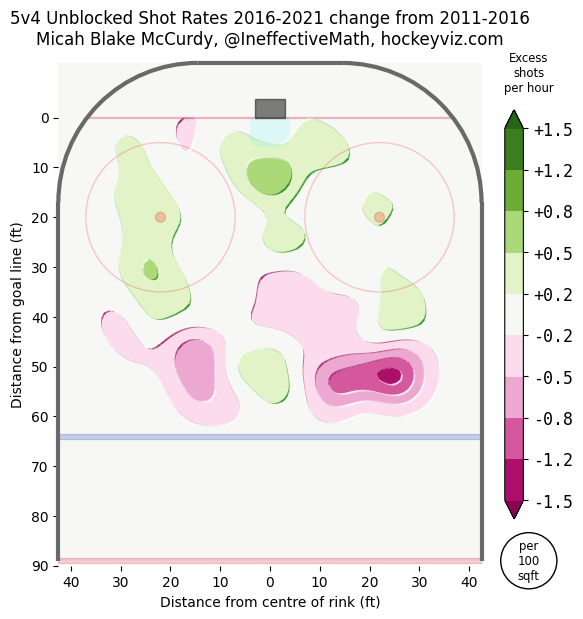

Ulmer's observation is spot-on. The data indicates five-on-four shots are being taken closer to the net than in years past. HockeyViz.com's Micah Blake McCurdy shared a visualization of this development with theScore for this story, comparing the change between two five-year periods:

The purple blobs represent decreases in five-on-four shot volume between 2011-16 and 2016-21; the green blobs represent increases. At the blue line, point shots have started to move to the middle and the overall volume favors shots from below the top of the circles.

McCurdy applauds the modern power play's aspirations to not only enter the offensive zone with possession of the puck - usually through the contentious neutral-zone drop pass - but also to use its initial possession wisely.

"If you take forever to get going, you're only going to get one or two shots (over two minutes)," McCurdy said. "When you look at rates, teams that are not taking a long time to set up look better, even when the shots they take aren't super impressive. Because if it all goes wrong, they have a chance to regroup and go again, maybe two or three or four times during a power play."

The Capitals, who this year rank third in the NHL in PP% and have iced a lethal power play for the bulk of Alex Ovechkin's career, launch a ton of power-play shots from the point (John Carlson), left circle (Ovechkin), and netfront (TJ Oshie). Washington's 1-3-1 has worked so well because the gravitational pull of the "Ovi Spot" creates shooting lanes elsewhere.

Good spacing, multiple options, and chemistry can help drive long-term results. "When you talk about sustainability, you probably need the players to be there and be in place for an extended period of time," Capitals head coach Peter Laviolette said. He later added: "They know where they're going to be, and they know where the outs are, and they know where to make plays and who's open."

The Jets' power play has cooled of late but over the season it's scored on nearly one in four opportunities (24.2%). "It's all about the rate of puck movement to open up 6 inches of ice and then a play gets made," Jets head coach Paul Maurice said.

"Take what's there, take what's given," he continued, "and get it simplified."

Some peripheral factors contributing to strong power plays include: players' skill levels being higher than ever before; continued advancements in stick technology, which give players extra zip on shots and passes; and the majority of first units, which tend to feature teams' top offensive talents, being leaned on heavily, sometimes staying out for the entire two minutes.

Ovechkin and Lightning sniper Steven Stamkos are themselves peripheral factors. The veterans' prolific power-play goal scoring has influenced a generation of triggermen, from bombers like Leon Draisaitl and Denis Gurianov to deceptive shooters like Auston Matthews and Kyle Connor. The Kings drafted Arthur Kaliyev 33rd overall in 2019 in part because of his Ovechkin-esque clapper from the right circle.

"Back in the day, how many guys really had a good one-timer? Brett Hull, and then not many others," Andreychuk said. "Now, every team's got two or three guys that they can rely on, guys who have that (dangerous) one-timer."

Meanwhile, the bumper guy has taken on greater importance in recent years. In the 1-3-1, he's first and foremost a support system for the four other power-play skaters, the teammate always nearby and ready for a quick give-and-go.

"It can cause a lot of confusion, especially if that bumper player is intelligent and understands where the pressure's coming from," said Mike Mottau, a former NHL defenseman who scouted for the Blackhawks from 2014-20. "That one little pass into the interior of the penalty kill causes the (killers) to pay attention to the bumper guy. He's in a prime scoring area."

Joonas Donskoi is the unheralded bumper on Colorado's stacked first unit. With Gabriel Landeskog in front, Mikko Rantanen and Nathan MacKinnon on the flanks, and Makar on the point, Donskoi retrieves loose pucks and relieves pressure to "get us to some open ice where we can get our heads up and use our skill to make plays," Avalanche head coach Jared Bednar said.

"He's very good at both of those aspects of the power play," Bednar added, "but one of the reasons I like him there is because he's a right shot and he pops into holes really well as a shooter. Teams tend to overcompensate or try to take MacKinnon away on his half-wall, and if Cale has to dump it back to Mikko, then he's got a shooter in there (with Donskoi)."

Here's some video evidence of bumper work by Donskoi (No. 72):

Cale Makar with the point blast! Second power play goal of the night for the Avs!#GoAvsGo pic.twitter.com/ZHUC5ggBje

— Hockey Daily 365 (@HockeyDaily365) May 1, 2021

Notice how Donskoi plays give-and-go with Makar, hustles back to support Rantanen, and then provides a high screen on Makar's shot from the point? That's the utility of the bumper and a surefire way to confuse penalty killers.

Interestingly, even the netfront guy's role has changed over time. He's popping below the goal line or into the corner to handle pucks, whereas Andreychuk - who's listed at 6-foot-4 and 220 pounds on HockeyDB - recalls being mainly stationary. And he absorbed plenty of abuse in the crease area.

"There was a time when you did need to support on the boards and go below the goal line, but you tried not to leave the front of the net," Andreychuk said. "If I could get position in front, it was going to be hard for the guy to move me. As soon as you did move to the goal line, it was a lot harder for me to get back to the front of the net, right? Now, they don't engage with that guy very often, compared to the past. You talk to goalies now, and that's his guy. That's the goalie's responsibility. It's not the defenseman's responsibility anymore."

All of this - the obsession with the 4F-1D and the 1-3-1 and the macro changes in and around the game - has altered a classic coaching metric. Years ago, you aspired to add up your team's power-play percentage (say, 20%) and penalty kill percentage (say, 80%) and hit that magical 100 mark.

"Now it's a little easier to hit 100," Ulmer said with a laugh.

Yes, heading into Thursday's slate of games, 15 teams were in the 100 club, with the Carolina Hurricanes sitting at a whopping 111.7 (26.6% plus 85.1%).

It's a different hockey world now, especially on the power play.

John Matisz is theScore's senior hockey writer. You can follow John on Twitter (@MatiszJohn) and contact him via email ([email protected]).