Mark Messier on leadership, Halloween parties, Cup journeys, and TV gig

Early in his NHL career, Mark Messier hatched an offseason ritual with his brother and a couple of friends: Spin a globe and fly to where his finger landed. Messier's crew rode motorbikes in Thailand, drank psychedelic tea at a Barbados hostel, and left a German nightclub as the sun rose to jet straight to Ibiza. The summer getaways rejuvenated him - how else could he have played 25 seasons? - and taught him things about the world.

"I was interested in the way people live. I was interested in different cultures and different ways of life and different practices and different spiritualities," Messier said. "I loved the adventure of the travel, but I also loved the education."

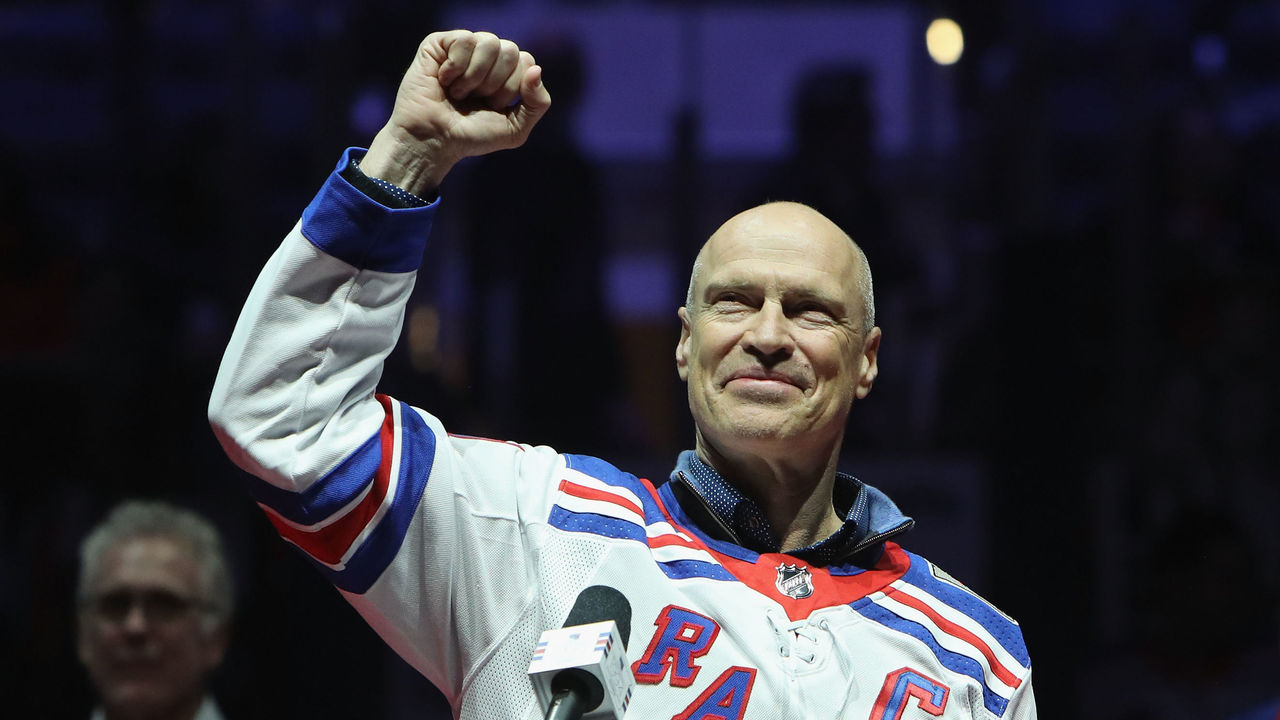

Messier reminisces about these trips in his new memoir, "No One Wins Alone," published Tuesday, which he wrote with sportscaster Jimmy Roberts. Elected to the Hall of Fame as soon as he became eligible in 2007, Messier remains hockey's consummate leader and power center. Few players scored and won so often. Between 1984 and 1990, he helped deliver five Stanley Cups to the Edmonton Oilers, the last of them after Wayne Gretzky was traded. In 1994, Messier captained the New York Rangers to their first title in 54 years.

His No. 11 is retired in Edmonton and Manhattan. Only Gretzky and Jaromir Jagr tallied more career points than his 1,887. He ranks third in games played (1,756) behind Patrick Marleau and Gordie Howe, the latter of whom Messier faced in the World Hockey Association when he was 17 and Howe was 51. Howe wheeling around the ice pregame, Messier wrote in his memoir, was the only sight in hockey that made him gulp.

Messier turned 60 last winter, and be it in print or on TV, he has memories, opinions, and wisdom to share. The book comes out two weeks into Messier's debut as a studio analyst at ESPN, the NHL's new lead U.S. broadcast partner. He's in the legend's chair that Gretzky similarly occupies at TNT, breaking down the game they used to dominate together.

Messier's travels, for business and for pleasure, have shaped his outlook on how to live and lead. He thinks that curiosity is powerful, that new and varied experiences enrich how people understand themselves. Within a team, Messier wrote, continuity and connectivity make winning possible. So does having leaders who inspire - players who preach selflessness to the rest of the group and then walk the talk.

"The overall purpose of writing the book was to give some insight into how powerful of an experience I had playing on a team," Messier said.

Messier spoke to theScore about a range of topics, including his TV job; the value of emotion, glue guys, and fall costume parties; and what he regrets about his late-career stint with the Vancouver Canucks. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: Broadly speaking, this book is about your career, about teamwork, and about your perspective on leadership. How would you define leadership in the NHL? In a dressing room, within a team, what is it that the best leaders do?

Messier: Leadership is so multifaceted. There are so many levels of leadership. Dealing with people. Getting people to believe in themselves. Setting an example. Being able to give correction without resentment. Establishing relationships.

It's one thing to go out on the ice and be a good hockey player and lead by example. There are just so many different elements of leadership that are important at the professional level because we're talking about livelihoods. We're talking about security for families. We're talking about the upheaval of families being traded if things don't go well. There's a huge responsibility. I don't think it should be heaped on some young player just because they're a good hockey player.

You won six Stanley Cups as a player.

I like to say we won six Stanley Cups. (Laughs)

Absolutely. One of your insights about winning struck me. A lot of players talk about the importance of staying even-keeled, of avoiding highs and lows. You believe the opposite: that you should feel high when you win and low when you lose. Why do you think that?

Hockey, and I think most sports, or anything you do with passion, is about emotion. You have to play the game with intensity. With that, there's going to be a fluctuation of state of mind. You're disappointed that you didn't play well. You're disappointed that you lost. You're disappointed that you made a mistake. You're disappointed that you made a decision off the ice that affected the team. And you're absolutely fired up and elated when you win - or when you played a great game, you scored a big goal, you made a great decision, you helped a teammate.

The ups and downs of a professional hockey player, it's not a flat-line sport. To try to quell that (emotion) is counterproductive, in my opinion.

Which of your championship journeys do you think about the most?

Now that I've been retired 17 years - 60 years old and thinking back on my career - it's all about the great and fun moments that we had in the dressing room. Those pressure-packed situations: We're in a 20-by-20 foot dressing room staring at each other before we take the ice. Getting dressed at the hotel in New York City and getting on a bus, walking out onto Park Avenue with our equipment on to go to practice.

The journey is the magic ingredient. Of course, you remember the seminal moment of the whistle blowing and hoisting the Stanley Cup and the banner being raised the next year. But it's all the special moments along the way, and the heartache and the heartbreak, and the great, uplifting moments.

After our first Stanley Cup, I'm not going to say there was an emptiness to it, but there was a little bit of a pause (where I thought), a week later, 'Geez, we're not going to the rink. That's where all the fun was.' You know what I mean? Not basking in the fact that we won. Of course, here we are years later and we can really relish the fact we won the Stanley Cup. But it's a whole year. How difficult it is, and how much you have to rely on each other, gave (the journey) such a big impact.

The book is called "No One Wins Alone." To make that point, you note that on your star-studded teams, a lot of guys contributed to the team effort - to winning - from the shadows. Who was an unsung hero of one of your Cup teams that people should know about?

It's always the role players - the players that you think are expendable at the end of the year, that you think you can replace easily - who are sorely missed. Not only because of what they're able to do as a role player, but what they brought off the ice into the dressing room, on the buses, when you traveled.

Those are the galvanizers. The glue guys on the team. They're not easy to replace. We're going to see that in Tampa Bay this year with the six players they lost because of the salary cap. (Blake Coleman, Barclay Goodrow, Yanni Gourde, Tyler Johnson, David Savard, and Luke Schenn all left the champion Lightning in the offseason.)

In the book, I talk about Mark Lamb, a guy who struggled to make it. Here he is (in 1990) playing between Esa Tikkanen and Jari Kurri. A journeyman who could barely stay in the league and here he is replacing Wayne Gretzky. You can't make that stuff up. He was such a great character guy and played such amazing hockey and was such a huge part of our championship team. Loads of character and grittiness and toughness.

Dave Brown - another guy who was an enforcer but was a huge part of our team (that post-Gretzky title season). I could list 50 guys right now who were important but never got the recognition they deserved.

I'm glad you mentioned Tampa Bay. To write about Edmonton's 1984 title, you brought up the experience and pride of the four-time champion Islanders and how hard it was to finally beat them. What do Tampa's opponents have to do this season to topple the champs?

(Tampa's) got the distinct advantage of having swum in the deep end now for a couple of seasons. When you win the Stanley Cup, it changes you. When you go back to back, it changes your knowledge of the game and how to win and how to prepare and what it takes.

Staying healthy will be a challenge for them. They're replacing guys that they lost who were great players, instrumental to their victories. Who's going to replace them? How are they going to bring (the new players) into the culture? How are they going to bring them up to speed, and (instill) the understanding and experience of what it takes to play in the playoffs?

It's not going to be easy. But it's not easy unseating anybody who's won a Stanley Cup.

It's remarkable what Tampa's done. Pittsburgh won back to back. A three-peat, history tells us it's not easy. There's been three organizations and five teams to ever do it. (The Toronto Maple Leafs in the 1940s and '60s, the Montreal Canadiens in the '50s and '70s, and the '80s Islanders.) It'll be interesting to see how that story unfolds.

Another belief you share in the book: The key to leading a successful hockey team is to throw a good Halloween party. Why is that?

When you come to training camp, you're super focused on getting acclimated to your team - even old players coming back again. Getting yourself ready for the season. It's a really intense, focused time for a team. You start the season with new players. You get through the first month of the season. (Halloween) always fell at a perfect time to let your guard down a little bit. Get away from the rink. Get the wives and girlfriends and the entire team together in an environment that's really fun and playful.

It brings out people's personalities. It's one of those things that you can all go back to the dressing room for the next couple of weeks and talk about. It's a team-galvanizing experience. Those shared experiences are critical to a team's success, in my opinion.

I want to ask about your arrival in Vancouver in 1997. You were named captain, replacing Trevor Linden, and you wrote that the way you handled the division in the locker room at the time was among your biggest mistakes in hockey. What do you wish you'd done differently?

Once you have a captain, you can't unseat a captain. It just doesn't work. I thought I was trying to do what was right by being a moderator (between cliques within the team). But in the end, it just wasn't the right thing to do. It didn't sit well with the fan base. It wasn't fair to Trevor. It just was a mistake. It was an honest mistake. It was something that I didn't do with any bad intentions. I was trying to help, but I was trying to help in the wrong way.

If I had to do it again, I would have tried to be in more of a support role for the players there and unify things from the rear. Leadership from the back is not a bad thing. It's very important. I had great leaders around me throughout my career. That's something I would have thought about doing differently.

You and Wayne Gretzky were born 10 days apart in 1961. You started in the NHL with the Oilers together. You wrote in the book that you're effectively family. Now he's analyzing games on TNT and you're working for ESPN. To what extent does that stoke your competitiveness?

I don't look at us as competitors so much. I look at us as a whole part of the ecosystem of the NHL. I think back to Saturday night at 6 o'clock, Hockey Night in Canada with Danny Gallivan and Dick Irvin and the great Foster Hewitt. Those people bringing the game right into our living rooms. I look at it as a chance to do what's been done so brilliantly for the last 60 years - of my life, anyway.

Hopefully, I'll be able to articulate some of the experiences that I had, some of the knowledge that I had, as a player. Articulate some of the challenges that the players face at different times. Hopefully, bring a perspective to the game that resonates with people.

What does it mean to get to do that at the same time as Wayne?

Our lives have revolved around the game of hockey. To have Wayne back in the game is great for everybody. To hear his perspective on the game, we're talking about the greatest, maybe, athlete of the century. The greatest hockey player of all time. To be hearing his insights, for me, as a fan, would be exciting.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- 5 key takeaways from Canada's hard-fought victory over Switzerland

- Report: Fiala to have season-ending surgery after Olympic injury

- Canada's Morrissey won't play vs. France, not ruled out of Olympics

- Finland rebounds with important win over rival Sweden

- McDavid, MacKinnon shine in Canada's win over Swiss