Set in stone: The history, beauty, and power of the Stanley Cup ring

Andy Moog was in a funk. It was the early 1980s and the Edmonton Oilers goalie found himself in a sour mood every time he set foot inside an arena. "Maybe I wasn't playing well. Maybe I was hurt, sick, tired - honestly, who knows," Moog says now.

One day, teammate Willy Lindstrom snapped. "Listen," he barked at Moog. "This is a once-in-a-lifetime chance. You're never going to get this again."

Lindstrom was talking about the satisfaction of victory, competing in packed buildings, team camaraderie. The NHL lifestyle vanishes in the blink of an eye.

"He made me really appreciate the moment, and I admire him for that," says Moog, a three-time Stanley Cup champion with those dynastic Oilers teams.

Moog tells this story over the phone while examining one of his three Cup rings. Two are locked inside a safety deposit box and stored at a bank, but he tends to keep his first - the smallest, plainest, and most meaningful - handy.

"There it is," the 62-year-old says as he describes his cherished 1984 ring. "You can put it on your hand and walk around. There's your connection to a Stanley Cup."

Moog is one of 1,452 players to be on a Cup-winning team, according to Hockey Hall of Fame records. Of those players, 844 have won one title and 608 have won two or more. Starting Monday, another crop of players will battle for the 2022 championship. Some of them, like Pittsburgh Penguins star Sidney Crosby, will be hunting a fourth Cup. Others, such as the Florida Panthers' 42-year-old Joe Thornton, will be chasing an elusive first.

Every year, the winning team's players, coaches, and staff pop champagne and celebrate the achievement, and the days-long party culminates with a city-wide parade. In the offseason, everybody gets the Cup for a full day, and their names will be eventually engraved onto pro sports' most iconic trophy.

Still, no single person owns the Cup. It travels back to the Hall of Fame after the offseason tour, and the cycle restarts each fall. Even memories of the Cup run can fade, losing their sharpness as the years and decades tick by.

The ring is what stands the test of time for individuals.

"It's the one tangible thing," Phil Pritchard, longtime caretaker of the Cup trophy, says of the ring's unique place in hockey culture.

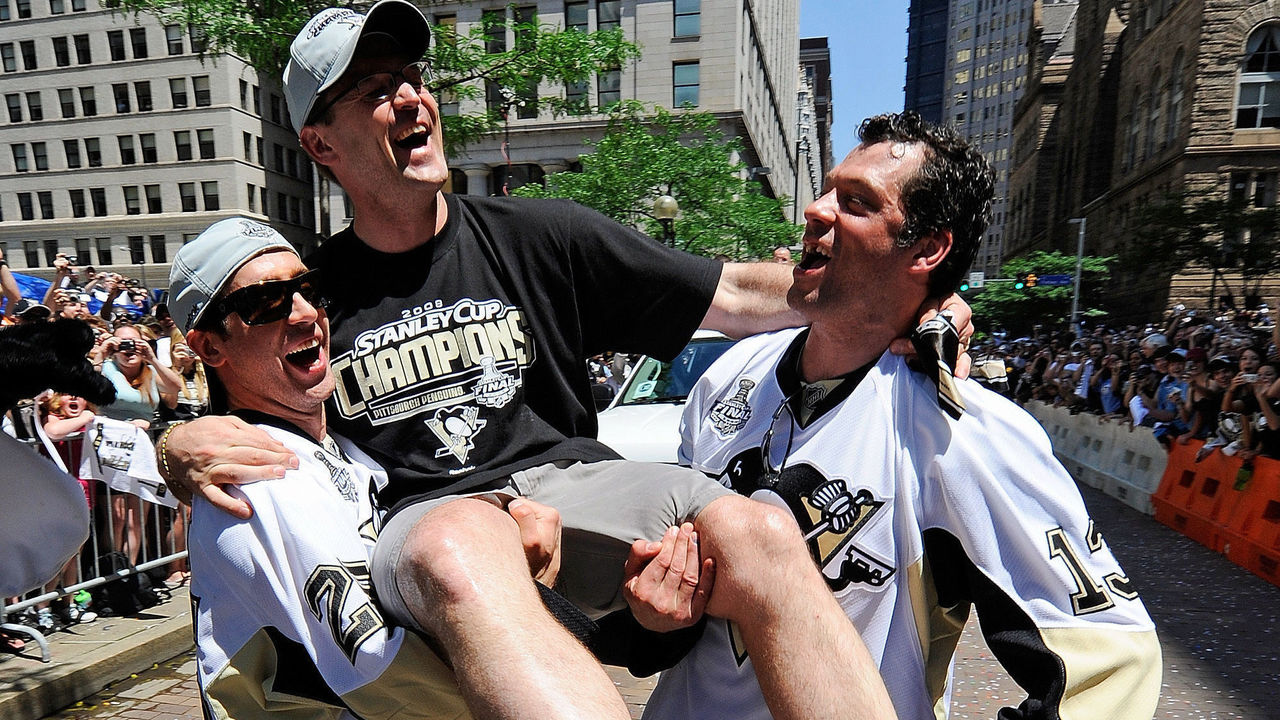

"You want to add that ring to your legacy, to your family tree, to who you are as a player or coach," adds Dan Bylsma, head coach of the 2009 Pittsburgh Penguins. "The ring is something you take with you forever."

The origins of the Cup ring can be traced back to the first Cup-winning team.

Seven players on the 1893 Montreal AAA hockey club are believed to have received a championship ring after finishing atop the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada standings with a 7-1-0 record. (The first Stanley Cup playoff games took place in 1894.)

A century later, in 1993, the daughter of forward Billy Barlow donated her father's ring to the Hall of Fame. The artifact has been on display ever since.

"It looks like a standard male wedding ring," says Pritchard, who runs the Hall of Fame's resource center. "It's basic. But what it represents is amazing."

Montreal players received watches for repeating in 1894, and again in 1902. In 1915, players on the Vancouver Millionaires got medallions. There isn't a complete database of Cup gifts; however, the Hall of Fame's working document lists the 1927 Ottawa Senators as the second team to issue rings.

The 1937 Detroit Red Wings were next to hand out rings, and in the 1940s, the Original Six club specially designed one so it could be used as a stamp ring.

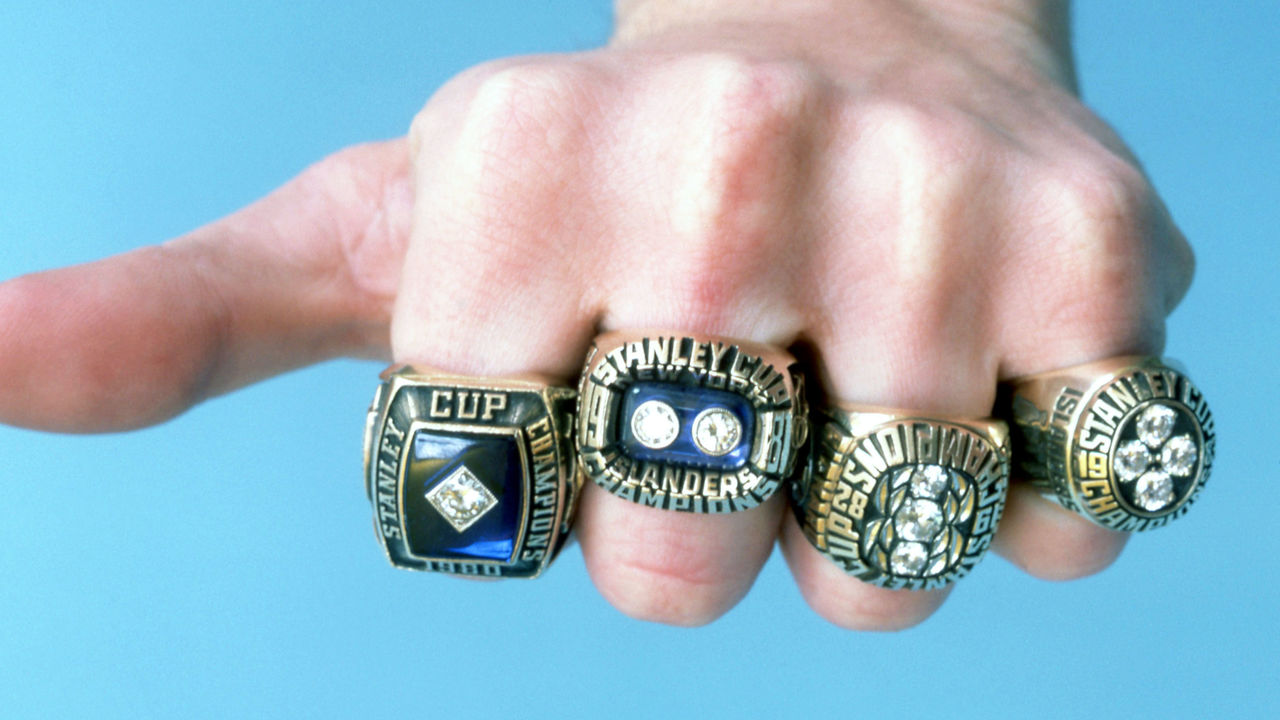

For the next few decades, teams rotated between presenting their players with gold rings and other gifts, such as cufflinks, pendants, and television sets. When owners did foot the bill for a ring, there were usually strings attached. Members of the 1960s Toronto Maple Leafs dynasty, for instance, received a single ring for all four Cups; instead of issuing multiple rings, the diamond on the original ring was enlarged each time Toronto won another title. (In 2014, the Leafs made amends to those players, issuing make-good rings.)

Rings finally became the standard during the 1980s. Now it's an unbreakable tradition; every Cup team creates a unique piece of bling.

The main difference between, say, 1981 and 2021 is aesthetics. As recently as the mid-1990s, Cup rings resembled a high school class ring - simple, elegant, wearable. Nowadays, they're closer to a trophy - extravagantly beautiful, intricately detailed, and utterly ostentatious in size.

"You need a shopping cart to move one of the new ones around," quips Jim Paek, a defenseman on the 1991 and 1992 Penguins. "Mine are tiny by comparison." Bylsma, owner of a modern ring, can confirm, noting: "It's not the easiest thing to cut a steak and have your ring on at the same time."

According to Miran Armutlu, the master jeweler at the ring-making company Jostens, the 2002 Red Wings "changed the industry." Early in the design process with Detroit, owner Marian Ilitch instructed Armutlu to "make my logo come to life" by coloring the iconic winged wheel with eye-catching rubies.

It was the first time custom-cut stones were incorporated into a pro team's logo, Armutlu says. "To this day, when people look at our collection of rings, it's one everybody's attracted to," he adds. "It's an unbelievable piece."

Jostens, which is headquartered in Minneapolis, has produced 15 of the last 19 Cup rings. Armutlu meets with team executives three or four times to hash out design elements before the manufacturing process begins. Common personal touches include a rundown of series scores, the name of the post-victory song, or the coach's top slogan.

The 2020 Tampa Bay Lightning wanted a "hidden story" on their ring, which carries 557 diamonds and 81 blue sapphires for a combined weight of 25 carats. The mini trophy at the center of the ring was specially configured so it could rotate sideways and reveal the word "STOCKHOLM" (for the site of the team's first two games of the year), two hockey sticks, and a black diamond representing a puck. The estimated retail cost per ring? A reported $66,000.

Players receive the highest-quality rings. From there, hundreds of other people - from coaches, athletic trainers, and equipment managers in hockey operations, to accountants, marketers, and salespeople in business ops - slot into tiers, and the caliber of their rings varies by level.

Owners often try to one-up one another - or, in the case of repeat champions, themselves. Rings have doubled in weight over the past two decades, Armutlu says, swelling from around 70 grams in the early 2000s to 140 grams, which is nearly a third of a pound.

"They've gotten to a point where we seriously try to talk the team away from making it bigger than the last one," Armutlu says. Asked if he foresees a time when the Cup ring reaches its maximum size and weight, the jeweler who's designed more than 100 different championship rings laughs.

"We're there," he says. "If it's going to get any bigger, I'm going to have to figure out how people are going to get two fingers through the ring."

Fresh off claiming the 1996 Cup, Mike Ricci and his Colorado Avalanche teammates were notified of an end-of-summer dinner at the last minute. Ricci figured the "mandatory" gathering had been called so management could deliver a lecture about turning the page and shifting focus to the year ahead.

Instead, the players were shown highlights of the '96 run on a giant screen, along with quotes from the movie "Rudy." A few minutes later, Daniel "Rudy" Ruettiger himself appeared. The event wasn't quite what Ricci had imagined.

"We actually got our rings from the real Rudy," he says.

Once a small, informal gathering, the ring reveal has evolved into a black-tie affair for players, coaches, staff, and significant others. The pomp and circumstance of the evening contribute to the ring's overall charm and aura.

Rick Tocchet, a forward on the 1992 Penguins, recalls looking at his ring for the first time during an event at LeMont, a five-star restaurant in Pittsburgh. In that moment, he felt fortunate. Acquired in a midseason trade, Tocchet had settled into his stall in a dressing room full of future Hall of Famers and lifted the Cup a few months later. Now he was sharing stories over drinks.

Tocchet owns two other rings (2016 and 2017) from his time as an assistant coach for the Penguins. When Tocchet gazes at that '17 memento, he pictures defenseman Ian Cole and his unmistakable post-Cup glow. Cole laid 13 body checks and blocked nine shots in third-pair minutes in the '17 Cup Final.

"He was a monster on the penalty kill to win the Cup. That's what I think about when I look at that ring," says Tocchet, now a TV analyst for TNT. "Sure, Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin, those guys were - and still are - phenomenal. But I think of the little guys and what they did to help us win."

For Ricci, the ring elicits a wide range of memories and emotions - the good days, the bad days, the elation, the dejection, and everything in between. And while the Avs swept the final, and the ring embodies that dominant four-game stretch, the fear of failure sometimes comes rushing back.

"Fear, and a hatred for the other team," he says. "That makes it even more special because it forced the group to come together and get really close. You realize it wasn't a guarantee; there are times when you were up against it."

When Ricci's wife sees the ring, she will ask, "Do you remember the bruise you had on your forearm?" Bruises fade, but the memories - and the ring -don't.

As for the current whereabouts of Ricci's beloved piece of jewelry ...

"If I told ya, I'd have to kill ya," he says dryly. "No, no, it's in a safe. I should answer that more truthfully: It's in a safe - I think."

All seven Cup winners interviewed for this story store their rings either in an easy-to-access spot - inside a medicine cabinet, for example - or behind lock and key in a safety deposit box at home or at a bank.

"It doesn't see the light of day much," says Max Talbot of the 2009 Penguins.

Given what it represents and the limited supply, a Cup ring carries tremendous monetary and sentimental value. This helps make them an easy target for theft, as evidenced by the pile of news reports about stolen rings.

Henri Richard, who played on a record 11 Cup-winning teams, was left with only one ring after getting robbed decades ago. When the burglar called Richard to offer his rings back in exchange for money, the Montreal Canadiens legend reportedly hung up in disgust. "No way I was going to pay for my own bloody rings," Richard, who died in 2020, recalled in a 2000 interview.

The vast majority of Cup winners find reliable storage within days of acquiring the ring. A select few aren't so cautious, and they tend to pay for it. Bylsma remembers one night a "management person" from the '09 Penguins joined the players' warmup routine and immediately regretted his jewelry choice.

"He threw the football and threw his ring right off with it," says Bylsma, now with the AHL Charlotte Checkers. "The ring was so heavy, it came right off with any motion. It ended up on the ground and had to be put back together."

Armutlu's heard all kinds of stories about lost or damaged rings. Jostens will issue a replacement, but only once "very strict protocol" has been followed. "We're not going to just make a ring because the player calls up and says it's broken," Armutlu says. "He needs to go to the team and get a letter from the president."

Rich Matthews, head equipment manager for the St. Louis Blues, lost his high school class ring a long time ago. He took it off one day and - poof - it was never seen again. "I don't want that to happen to one of my Cup rings because they're irreplaceable," says Matthews, who owns a ring from each of his three stops: the Dallas Stars (1999), New Jersey Devils (2003), and the Blues (2019).

The Stars ring could easily be gone too. As the family was moving from Dallas to New Jersey in the offseason of 2000, Matthews' wife convinced him to stash the '99 ring and the mini Cup that goes with it in his vehicle for the cross-country drive, just in case.

The moving truck carrying the family's belongings was involved in a multi-vehicle crash near Biloxi, Mississippi. The truck driver died in the crash and most of the family's cargo was unsalvageable. The fiery accident and the driver's death still haunt Matthews.

"I don't tell that story to too many people," he said.

The '99 ring is a memento of a thrilling, then difficult, part of their lives.

"I'm not a player, so it takes a lot more for those guys to win," says Matthews, who's been to six Cup Finals. "But it does take a lot out of us equipment guys too, being on the road and preparing and giving the players the best chance to win every night.

"Winning a Cup does mean a ton to us. You take the rings out every once in a while and reminisce. It brings back so many memories. It's all pretty cool."

On a tombstone somewhere within a Toronto cemetery, there's a picture of the Cup. In the photo, Pong Paek, the man signified by the tombstone, is raising the giant trophy proudly, his son Jim having just won the '92 Cup.

"I still remember giving that ring to my dad," says Jim Paek, his voice faltering during a phone interview on March 14 - the 10th anniversary of Pong's passing. "I get choked up thinking about it - how happy he was, the tears, him jumping for joy."

Paek's other ring ('91) went to his mom, Kyuhui, who now has Alzheimer's disease. Kyuhui used to wear it all the time, even while working at the duty-free shop inside the Toronto airport. "All of the referees and coaches would come in and buy their liquor, so she got to know a lot of the people," Paek says. "She would show off the ring. She was very proud of me."

Paek, the NHL's first Korean-born player, was a bubble guy, not a star. He says his parents' support had an incalculable influence on him reaching the best league in the world. Gifting them his rings was a no-brainer. "I truly believe I wouldn't have won those Cups if it weren't for my parents," he says.

Darrell Davis, the son of former NHL winger and amateur scout Lorne Davis, is in possession of one of his father's six Cup rings. Technically, the Canadiens didn't issue rings in 1953, but a jeweler managed to turn ownership's gift - a sparkling tie tack shaped in the team's logo - into a nice ring.

Lorne wore his wedding band on his left ring finger, and the Canadiens Cup ring on his right. In 2005, two years before he died, the Habs sent proper rings to members of the '53 team. Suddenly, Lorne had two of a kind - and the perfect Christmas gift for Darrell, a longtime sports reporter based in Saskatchewan.

"I broke down crying," Darrell, now 64, says. "I never asked him for it, he never told me he was going to give it to me, but I opened the box, and yeah, I was a little puddle in the corner."

Lorne Davis' rings are on the long-established succession plan: Keep it in the family tree. "What's the old credit card commercial?" Darryl says. "Yeah, it's priceless. It doesn't have a cash value in our minds. It has emotional value."

Talbot, who scored Pittsburgh's only two goals in Game 7 of the '09 Final, will pass his bling onto his kids, too. "There'll be a cage with the three of them, a lion, and the ring in the middle. We'll see who comes out with it," he jokes.

Talbot last played in the NHL in 2016, retiring from pro hockey in 2019. Of late, he's been reflecting on his career more often, with the gold ring and silver trophy front of mind. "It's a nice reminder because sometimes it feels like another life, even though I stopped playing four years ago," he says.

His coach for that Cup season - the first of Crosby's career - can relate.

"Occasionally," Bylsma says, "I'll get my ring out when I'm just by myself and having a glass of wine and reminiscing about being a Stanley Cup champion."

John Matisz is theScore's senior NHL writer. Follow John on Twitter (@MatiszJohn) or contact him via email ([email protected]).