How Ken Dryden remembers the Summit Series, 50 years later

When Hockey Hall of Fame goalie Ken Dryden was about 3 years old, he fell off a rickety bridge on a nature trail in his hometown of Hamilton, Ontario.

Fortunately, water broke his fall.

"Somebody had to dive in and rescue me," Dryden recalled.

This occurred in the early 1950s, so Dryden, who turned 75 in August, isn't sure his recollection is entirely accurate. "I feel like I can remember it," he told theScore in a recent phone interview, "except I remember it as if I am watching myself, as if I'm seeing myself distraught on the grassy edges of the stream. Everybody's milling around me."

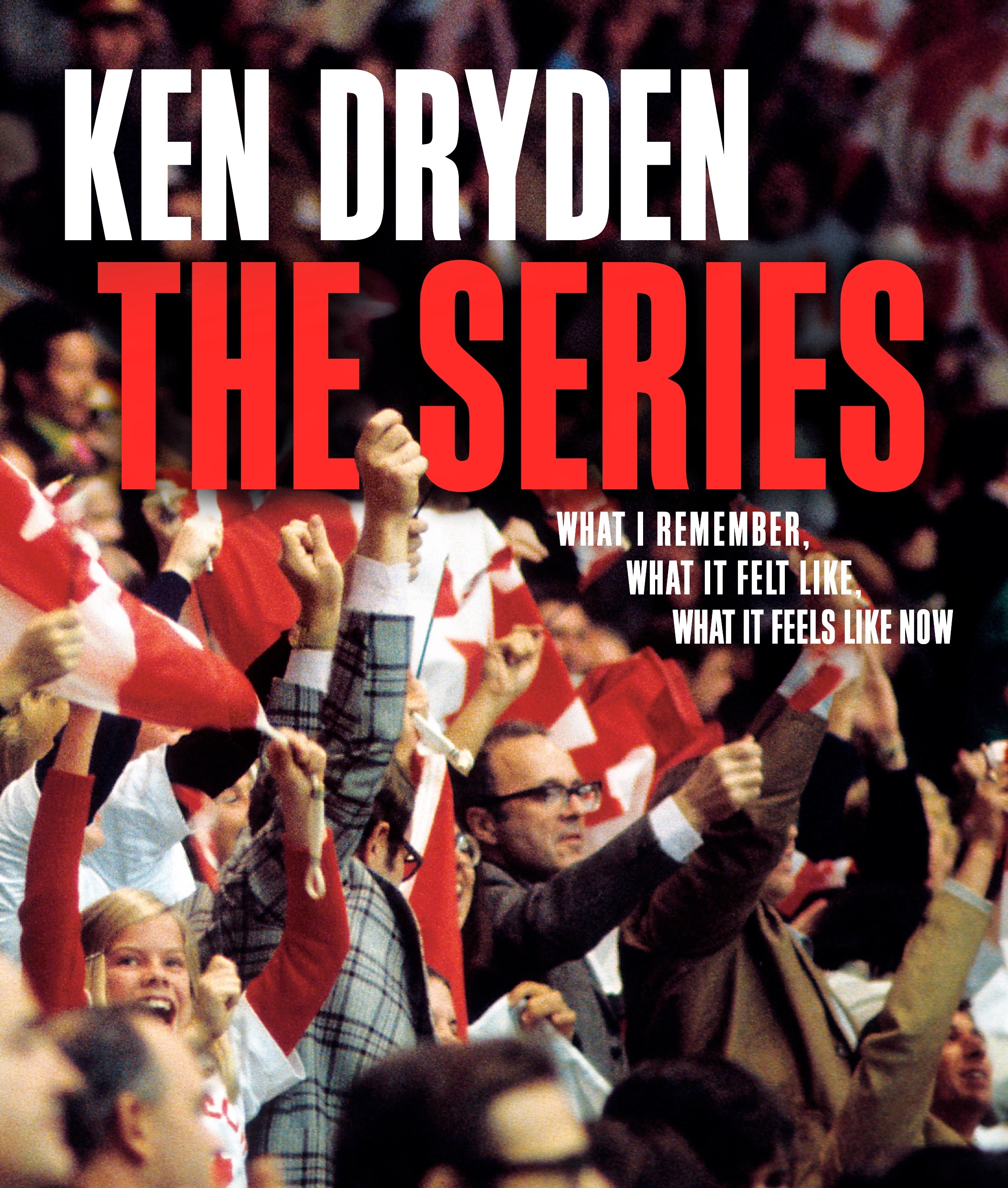

He places memory front and center in his new book, "The Series: What I Remember, What it Felt Like, What it Feels Like Now." Dryden immersed himself in law, politics, business, and publishing following a relatively brief but prolific NHL career with the 1970s Montreal Canadiens. Now he's finally tackled the 1972 Summit Series in depth after turning down multiple offers to do so over the past five decades.

Friday marks 50 years since the puck dropped on the eight-game showdown between Canada and the Soviet Union. The 1987 Canada Cup and 2010 Olympics are glorious events for Canadian hockey fans, but, as Dryden explains, nothing compares to the Summit Series. It was an inflection point for the sport, win or lose.

"Up until that moment, hockey was a Canadian game," Dryden said. "It happened to be played by some other people, but really it was a Canadian game. And because Canada's way was the best version of it, it meant it was essentially the only way to play. If you were somebody other than Canada, you were looking to replicate or fail. It was really at that moment - when another style of play showed it could compete at the top - that the mind started to open, and say, 'Well, if there's actually another way to play, then that means that there's a third way to play and a fourth and a fifth and a 10th way … '"

"The Series" doesn't rely on archival research or retrospective interviews with teammates like Phil Esposito and Bobby Clarke or a rival such as Vladislav Tretiak. It instead blends Dryden's own experiences playing for Canada with images from the early '70s, including black-and-white photographs and handwritten letters. Dryden wrote the 191-page book in a style that's similar to a diary or travel journal so the reader, regardless of age, can feel as if they are living the series for the very first time.

"What you're left with is the vivid stuff - the vivid wonderful, the vivid awful, the vivid strange, the vivid funny. It has to reach a certain level or it's probably going to fade away," Dryden said of accessing his memories. "That's why this series was so remarkable: 50 years later, it leaves a vivid path of memory."

Dryden strongly believes the final game - a 6-5 win to give Canada the 4-3-1 series victory - is the "most shared moment in Canadian history." It's hard to disagree considering the Cold War overtones of the matchup and the fact that a reported 73% of Canadians (from a population of 22 million) tuned in during the middle of a work/school day to watch Paul Henderson bag the winning goal ("Henderson! Has scored for Canada!").

"Want to know the definition of 'the country's stopped?'" Dryden said. "That's it - 16 out of 22 million. It stopped during a time it wasn't supposed to stop."

Dryden's most vivid Summit Series memory isn't Henderson's heroics, Clarke's controversial slash in Game 6, or Esposito's famous speech to an angry and frustrated hockey nation after Canada's best players were 1-2-1 in the four games in Canada. No, Dryden best remembers the 3,000 Canadians on the ground in Moscow for the final four games chanting, "Da da, Ka-na-da, nyet, nyet, So-vi-et!"

"There was no bucket-list thinking in 1972. Of those 3,000, I don't think there were many more than a couple of hundred where it was an easy ride for them financially to make it to Moscow for 10 days," he said. "Most of them didn't have a whole lot of money, but there was something about hockey and something about Canada and something about the connection between the two that meant they knew they had to be there. We experienced that feeling."

Dryden, a six-time Stanley Cup champion and five-time Vezina Trophy winner despite playing only eight NHL seasons, manned Canada's crease in Games 1, 4, 6, and 8, while Tony Esposito, Phil's brother, played the others. Virtually no one in North America - players, coaches, media, fans - had given the relatively unknown Soviets respect in the leadup to the series. Yet Canada found itself down 1-3-1 heading into Game 6.

The Soviets played a puck-possession style that was foreign to the Canadians. Tretiak was equally as adept at stopping pucks as Dryden and Tony Esposito, if not more. The pressure was on, and Dryden felt it physically.

"When I woke up the next morning, my legs felt like jelly," Dryden writes of the buildup to a do-or-die Game 8. Later, he adds, "I got nervous in my stomach. I never got nervous in my legs. I never got nervous two days before a game."

In one of the most revealing sections of "The Series," Dryden ponders an alternative ending. Five decades on, he still occasionally thinks about what would have happened if Henderson hadn't scored with 34 seconds left in the third period. What if the Soviets had snuck a puck past Canada's goal line instead? Would everything be different for Dryden, his teammates, Canada?

"All that vitriol from Vancouver and 10 times more would have come back at us," Dryden writes, referring to the booing that preceded Phil Esposito's emotional speech. "Fingers would be pointed. I might have been history's goat."

Dryden also admits a part of him wishes he wasn't on the Summit Series team. Not because he doesn't appreciate the experience - he's eternally grateful for his role - but because those who played in the final game missed out on the ultimate communal experience for Canadians of a certain age.

"A friend of mine told me a story about working as a manager for a moving company. This is late September, remember, and so much of moving happens in September. It's their busiest time of year," Dryden said.

"But they decided they were going to watch the final game. So what did they do? They looked around at all of the stuff that they were supposed to deliver and found the best TV. They brought it out, watched the game on it. Great story. And as an offhand comment at the end, my friend said, 'The phones never rang.' Isn't that amazing? At the time when the phones always ring, they never rang. That's what I missed. That's what all of us in Moscow missed."

John Matisz is theScore's senior NHL writer. Follow John on Twitter (@MatiszJohn) or contact him via email ([email protected]).