Why do players choke under pressure? For the same reason monkeys do

Players choke in every sport. They brick shots, botch kicks, muff passes, flub catches, blow coverages, forget assignments, and misread the scoreboard at the worst times. Some balk at handling the ball, dishing it off like a hot potato and placing the onus on a teammate to triumph or fail. Coaches perplex and enrage fans with the weird decisions they make as stress mounts and the clock tick, tick, ticks …

Certain kickers and fielders are best remembered for screwing up royally in the postseason. Some player is bound to make a costly mistake in the upcoming NBA Finals or Stanley Cup Final.

Choking is inescapable elsewhere in life too. Public speakers stammer. Test takers freeze. Even monkeys wilt under pressure. Scientists in Pittsburgh found those animals acted cautiously and consequently performed worse when the reward they were offered for nailing a complex reaching task became monumentally big.

Neuroscience explains this is inevitable: Brains are wired to choke.

"If you have a system that works optimally in the usual circumstance, it's going to work suboptimally in exceptional circumstances," said University of Pittsburgh bioengineering professor Aaron Batista, who was part of the research team that studied choking in monkeys.

Choking is a paradox. When the incentive to perform peaks, execution worsens. To probe the roots of this phenomenon, Batista and his colleagues devised a kinematic experiment.

The researchers trained monkeys to control a cursor on a screen, as if the animals were playing a Wii game, and reach when prompted for a small target that appeared somewhere beside, above, or below their hand's starting point. The monkeys were shown a cue that indicated the size of the reward - small, medium, large, or "jackpot," delivered in the form of sips of juice or water - they'd receive if they hit and held the target before a timer expired.

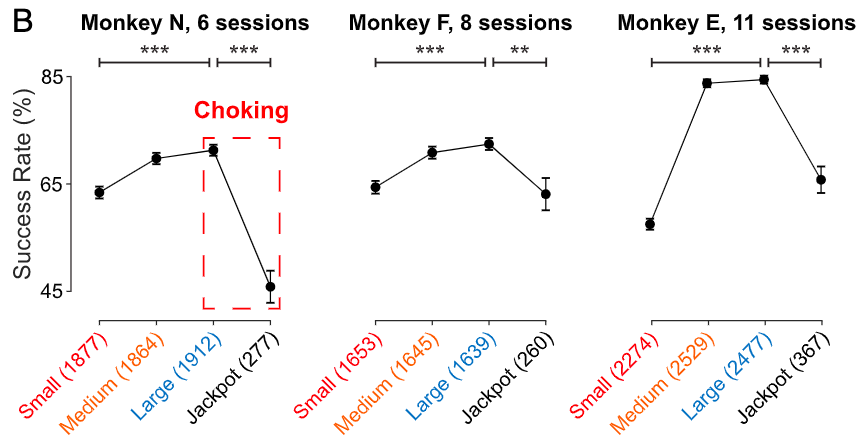

The monkeys' success rate over thousands of trials followed an inverted-U arc, the researchers first noted in the scientific journal PNAS in 2021. Each animal was imprecise with the small reward at stake, often overshooting the target seemingly out of carelessness. Locking in, the monkeys performed better when the medium reward was obtainable. They were maximally accurate with the large reward on the line.

The jackpot reward rattled the monkeys, though: The prize appeared for 5% of the trials, and when it did, their performance cratered. Suddenly, the motivation to succeed was debilitatingly high.

"There's a whole spectrum where incentives can help you dial in precise behavior," Batista said. "But at either end, things go awry."

Every monkey in the study showed the propensity to choke, said researcher Steven Chase, a biomedical engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University. They choked consistently, faltering at the beginning, middle, and end of sessions. The monkeys frequently didn't reach far enough on jackpot attempts, betraying their apparent overcaution, though they occasionally erred for other reasons.

"Some of them would try to cheat toward the target slowly. Some of them wouldn't be able to hold the target when those jackpot rewards came up. They were jittery at the end," said Adam Smoulder, a Carnegie Mellon biomedical engineering PhD candidate who was one of the study's lead authors.

"There were (these) weird little idiosyncrasies that we saw, which is something I like relating to humans."

Concluding that monkeys and people might share neural mechanisms that spur choking, the researchers set out to chart what happens in the brain when a huge reward is proffered.

They conducted more reaching trials, tracking how reward magnitude influenced the activity in a monkey's motor cortex. Their observations, posted online in April, have yet to be peer-reviewed by independent experts. The scientists posit that monkeys choke when reward cues cause a deficit in the information they use to plan their movements.

The researchers reported seeing neural activity conform to the same inverted-U arc as performance. The monkeys' brains processed more information about the target as the reward increased from small to medium to large.

That changed when the jackpot reward surfaced. Motivational signals appeared to overload the system, clouding the information the monkeys used to plan their reach, before they reliably undershot the target.

"On those jackpot reward trials, those planning signals are weaker. They have less information about what's about to happen than if the reward is just large," Chase said. "If the reward is large, those planning signals are as big as they get."

What does this mean for mankind - and for how we perceive chokers?

For one thing, maybe fans ought to be more lenient in their treatment of players who fold in the clutch. Their brains set them up to fail.

On the other hand, a key difference separates us from the animals: Monkeys always choke, but that isn't true of people. Some players, Chase said, seem to be able "to outwit the system - to think of strategies or ways to approach those high-pressure events that allow them to be calmer and succeed."

The scientists' choking research continues. They received grant funding to investigate if dopamine is the neurotransmitter that floods the motor cortex and inhibits motor planning. In the meantime, they'll applaud any athlete who enters the zone and is able to hit the jackpot.

"There's majesty and power and beauty to being someone who's managing all these feelings and still performing at the absolute top of their game," Batista said. As a viewer, he added, "It keeps you riveted."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.