How sport helped keep freedom alive in Czechoslovakia under Soviet rule

In the summer of 1983, Dominik Hasek - future Hockey Hall of Famer and six-time Vezina Trophy winner - learned he had been drafted into the NHL by happenstance after his traveling companion glanced at a newspaper while visiting France.

Not only was getting drafted a surprise but so too was the rookie contract he was later offered by the Chicago Blackhawks: five years and $1.2 million, which he had absolutely no intentions of accepting. Hasek, who was visiting France with his longtime Czechoslovakian national team teammate Frank Musil when he learned of the NHL's interest, could only relocate to the United States if he was willing to defect from the then Soviet-controlled nation, something hockey players had been tortured and imprisoned for attempting in the past.

Hasek eventually did play in the NHL, becoming one of the league's most celebrated goaltenders. In fact, a talented core of Czech and Slovak players put its mark on the NHL once the Soviet Bloc started to crumble in the late 1980s, including Hasek, Musil, Jaromir Jagr, Patrik Elias, Milan Hejduk, Petr Nedved, Bobby Holik, and David Pastrnak for the Czechs, while Marian Hossa, Marian Gaborik, Peter Bondra, and Zdeno Chara led the Slovaks. How hockey flourished there to become a pathway to the rest of the world is a story that began more than 75 years ago in 1946. It's a story detailed in Ethan Scheiner's newly released book, "Freedom to Win." It's a story that begins with Holik's father.

"By far the most important thing is what the men of that previous generation did for our generation to have opportunities," Holik said.

In 1948, on the heels of World War II, the Communist Party seized power in Czechoslovakia, heavily guided by Soviet influence. The regime was repressive from the outset, and dissent was out of the question.

These circumstances would color the childhood of Holik's father - Jaroslav Holik Jr. - who was born in 1942, just in time to fall in love with hockey in the brief lull between their Nazi occupiers and the rise of the Communist Party. It was Christmas morning in 1946 when he received his first pair of skates - money for which his parents had scrupulously saved from the proceeds of their small butcher shop that also doubled as the family's living quarters.

The idyll didn't last long. Two years later, the Communist government forced Jaroslav Sr. to sell the butcher shop at a price they named, and the future began closing in on the family, like most in the country at the time.

"We would never say, 'I want to do this with my life,'" said Bobby Holik, who was born into the repression in 1971. "We had no idea. Because, at any given moment, the government was so powerful that it could end any path."

But at the start of the Communist Party's rule, Bobby's grandfather - Jaroslav Sr. - imparted a fateful lesson about the future. He told his sons, "If you want to get anywhere in life, you have to play a sport. It won't happen any other way." It was their path out of tyranny.

In the late 1960s, Czechoslovaks were increasingly dissatisfied with their stalled economy, and signs of defiance grew, causing their new leader, Alexander Dubcek, to initiate the "Prague Spring" reforms at the start of 1968, which seemingly signaled a period of political transformation and increased civil liberties.

But those who dared to believe the era of Soviet dominance could be drawing to a close were disappointed. The Soviet Union was prepared for a show of military might, and on the evening of Aug. 20, 1968, it launched a full-scale invasion with four allied nations - the Warsaw Pact invasion - that sent shockwaves through the nation.

Initially, Czechoslovaks resisted. But as the Soviets clamped down, the avenues of resistance narrowed. That's where hockey comes into play.

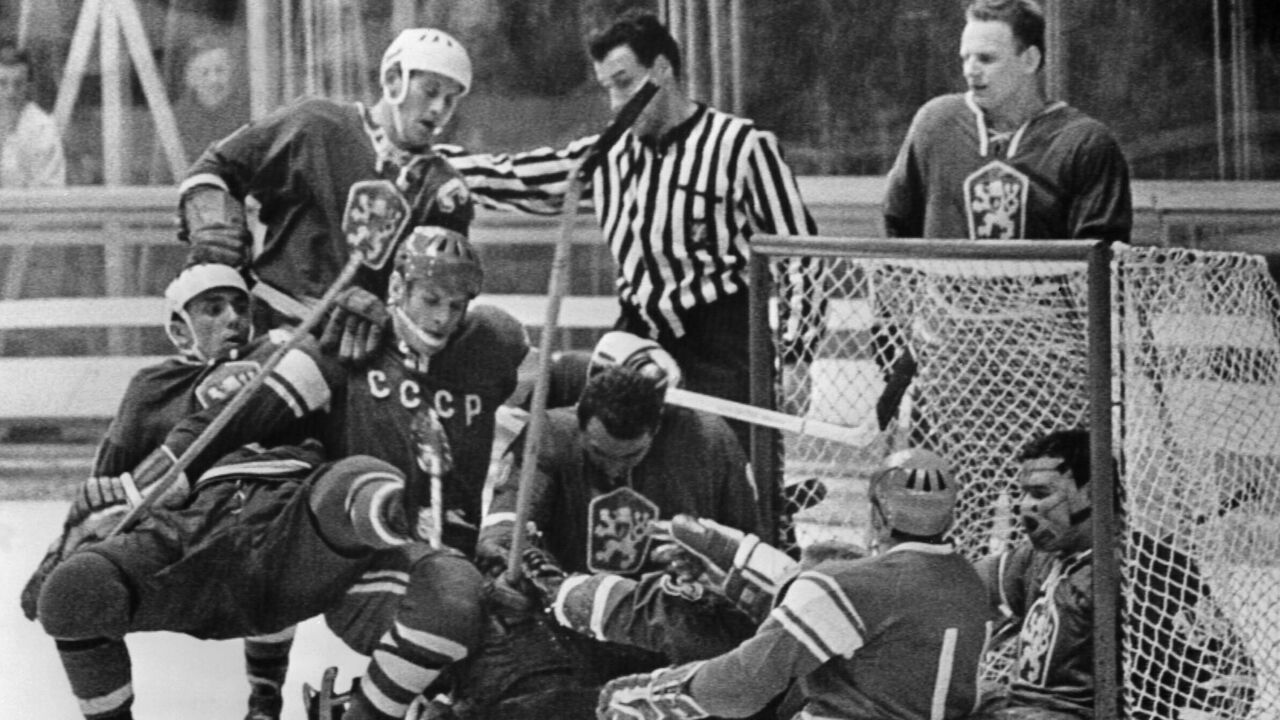

The occasion: The 1969 Ice Hockey World Championship. The event had been awarded to Prague, but organizers sought to avoid trouble and moved it to Stockholm. Czechoslovakia would have to wage its proxy battle against the Soviets on neutral ice.

"Sometimes you have no other outlet," said Scheiner, whose book delves into the Czechoslovakian team's two triumphs over the USSR at the tournament. "This was actually one of those cases where there was no other way for these people to get back at the Soviets or to express themselves in any way."

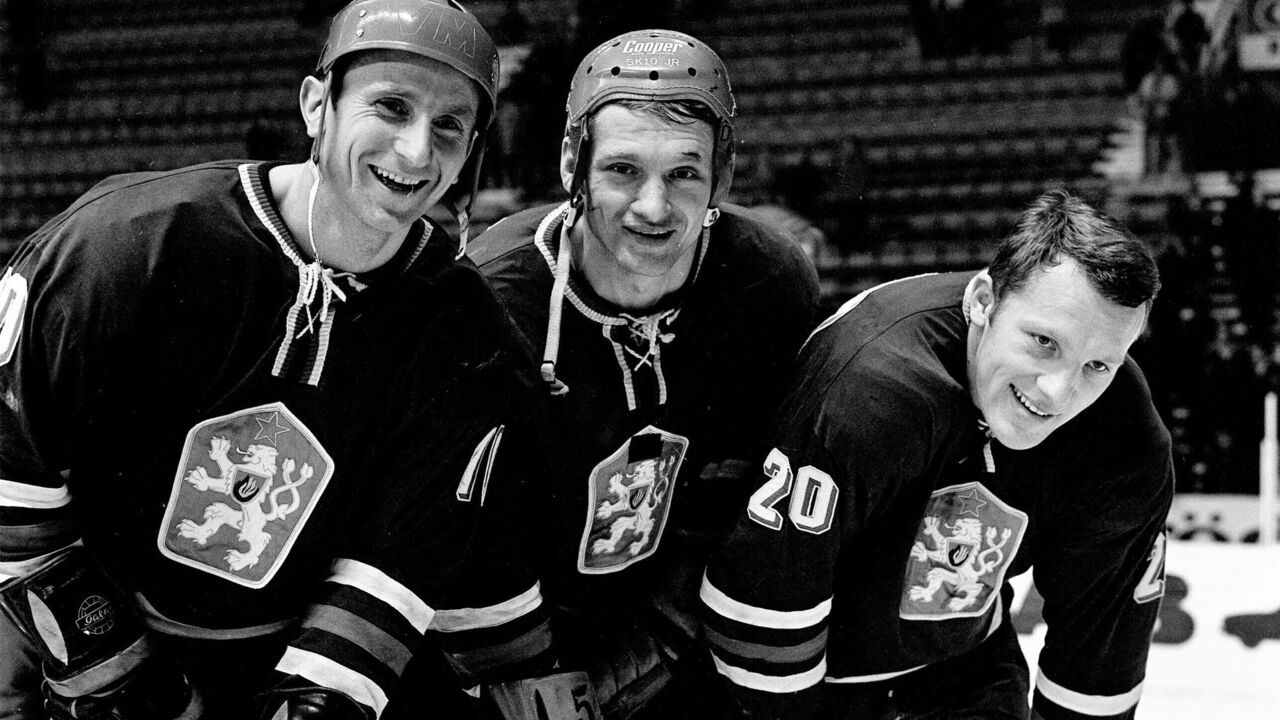

By then, Jaroslav Holik Jr., following his father's advice to create his future in sports, had made a name for himself as a dominant force on the ice. He had earned a spot on the national team, along with his brother Jiri, and they took their fighting spirit to the ice - something that took on a special weight for fans.

"Hockey was basically the national identity," Bobby Holik said. "We didn't have much at the time; we were occupied by the team that was far superior than we were. We were occupied by a country that had a hockey team that was the most superior hockey team in the world."

The Soviets came into the 1969 tournament having won the previous six world titles and the last two Olympics. The Czechoslovaks hadn't won a match against them since 1961. So prolific was their losing record that a rumor had circulated in the intervening years that they were forbidden from winning against the region's political masters.

That said, by 1968, the Czechoslovaks had improved greatly on the ice and managed a high-stakes win against the Soviets at the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble but ultimately placed second in the tournament after tying with Sweden in their subsequent matchup.

"Originally, the Soviet Union had no interest in competing with the West in these sports," Scheiner said. "But once they saw that they could get actual, real propaganda out of it, then they were really enthusiastic about doing it."

The Czechoslovaks sought to prove that while their country's liberalizing reforms might have been rolled back, at least on the ice, they would still dominate.

The 1969 tournament was a six-team affair that also featured Sweden, Finland, Canada, and the U.S. Each team would play the others twice in the round robin, with the title being decided by the team with the best overall record. Czechoslovakia would have two swipes at their tormentors.

"The situation just presented itself to make it stand," Holik said. "It wasn't politics. It was a national pride. It was national identity."

The first of their matchups fell on March 21. Czechoslovakia came into the game with a 3-1 record, having beaten Canada, the U.S., and Finland by at least three goals but losing 2-0 to Sweden. The Soviets had rolled to four straight wins over the same teams, scoring 34 goals and allowing just six. Half of those goals came in a 17-2 drubbing of the U.S.

The Czechoslovak players didn't let that bother them. In an intense battle - with the Swedish crowd adopting the Czechoslovaks as the hometown team - they secured a stunning 2-0 victory. Jaroslav Holik Jr. celebrated the first goal by ripping the net from the ice and tossing it toward the boards. Emotions were running so high on the Soviet side that coach Anatoli Tarasov suffered a heart attack before the final whistle blew.

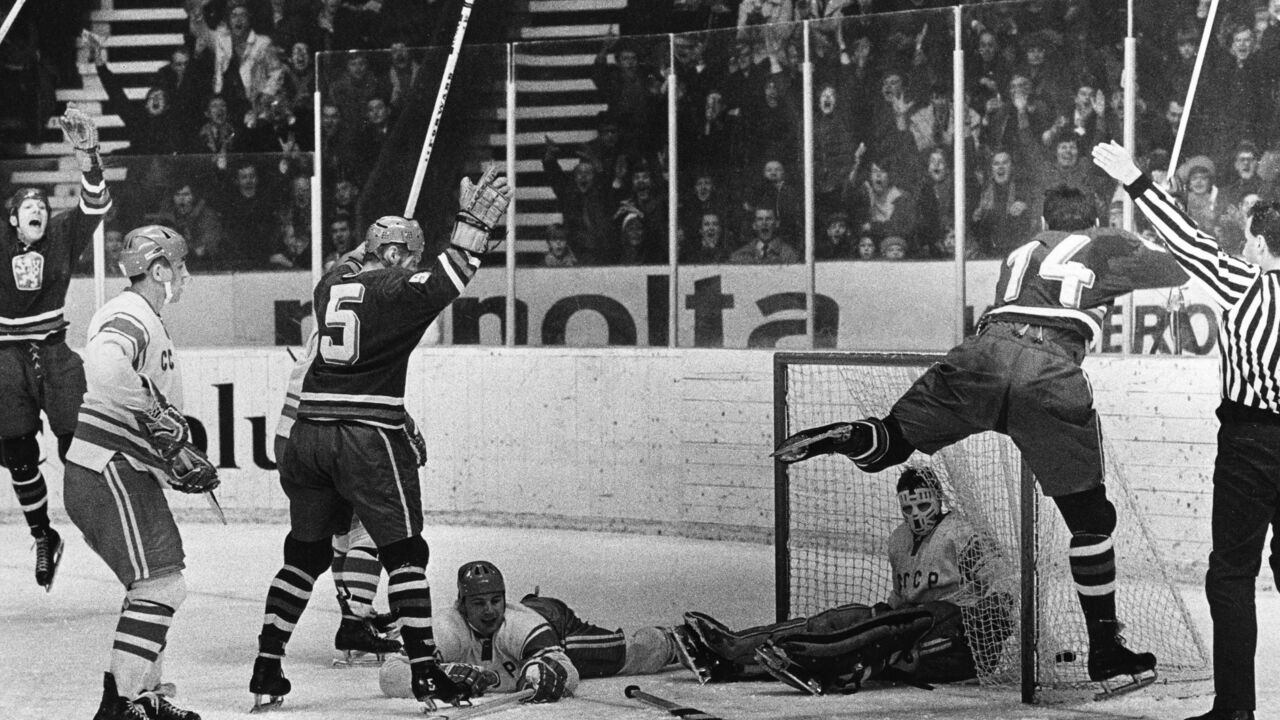

In their second encounter on March 28, the intensity ratcheted up another level. Both teams were 7-1 with two games left to play. Czechoslovakia drew first blood and secured a two-goal lead - the first goal of which was scored by Jiri Holik. But then the team faltered, giving up two before the end of the second period. Both teams remained locked in a stalemate until the middle of the third period when Czechoslovakia rallied with two goals - one of them by Jaroslav Holik Jr. - and held off a late Soviet rally to clinch an extraordinary 4-3 triumph.

The victory of the Czechoslovakian hockey team roused the nation to action. Half a million Czechoslovaks took to the streets in celebration that turned to defiance and protest. Not even Soviet military barracks were safe from the unleashed anger of the masses.

But the tournament and the protests didn't have a Hollywood ending. Czechoslovakia lost its final game to Sweden and was relegated to the bronze medal, while the Soviets earned gold. The protests also didn't result in any gains. "After these hockey matches, the repression got even worse in Czechoslovakia. That led to the reformist leader getting kicked out of power," Scheiner said.

With reform fully squashed, Jaroslav Holik Jr. did what he knew best, returning to hockey while passing down his father's nugget of wisdom to his own children: Sports were the only way out. Those children happened to be Bobby Holik and his peers, Musil and Hasek.

"One of my favorite parts of the story was all these boys who grew up in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and the 1980s. They were living in this horribly repressive society. But their parents would tell them, 'OK, in 1968, we were invaded by the Soviets. Their troops are still here. But, back in 1969, our hockey players were some of the few people who were able to fight back," Scheiner said.

The memory of that victory and its national importance spawned a generation of world-class hockey talent. A few defected: The Holiks' teammate Vaclav Nedomansky escaped in 1974; the Stastny brothers went out in 1980. Nedved was the last to go that route in 1989.

"It was just like, 'You have to be a really good athlete, and that will help you find your way out, or you're going to live in this country forever,'" Bobby Holik said.

Czechoslovakia would endure another two decades of Soviet rule before it successfully toppled the Communist Party regime through the Velvet Revolution in late 1989. While some hockey players - such as Musil, who defected in 1986 to play for the Minnesota North Stars - found escape routes during the Communist Party rule, other Czech and Slovak stars, such as Jagr, Holik, and Hasek, realized their NHL dreams following the fall of the regime. Jagr chose to wear No. 68 in the NHL in tribute to his grandfathers and the brief taste of freedom the country experienced that year.

In 1998, they did get their Hollywood ending. The Czechs bested the Russians 1-0 in the ice hockey final at the Nagano Winter Olympics to earn gold.

"There's no way (our parents) could change what happened or what was going to happen - the oppression that was going to be there. But they had an opportunity to just say, 'You know what, occupiers or not, we can still compete on the ice,'" Holik said.

Jolene Latimer is a video producer and feature writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- One big question for each Olympic men's hockey medal contender

- Matthews named Team USA captain: 'Honored' to play at Olympics

- Crosby named Canadian captain for Olympics with McDavid, Makar as alternates

- X-factors for top teams in Olympic men's hockey

- Germany adds Draisaitl 8 years after its top hockey achievement at Olympics