Revisiting the NHL's 1940s gambling scandal and the young star at its center

If things went right for Don Gallinger, he might have been remembered by history as a 17-year-old star who leapfrogged from Junior B to the NHL and became good enough to lead the Boston Bruins in scoring following World War II. But it's not how he entered the league that he's remembered for - it's how he left.

"There's absolutely no redemption in this story. But that's the real story," says hockey historian Fred Addis, who recently wrote "Gallinger: A Life Suspended," a book about Gallinger's fall from grace. "Once he fell off that pedestal, boy, he wasn't likable," Addis says.

In 1948, Gallinger was handed an indefinite suspension from the NHL when it was discovered he'd been betting on Bruins games, along with teammate Billy Taylor. That cloud followed Gallinger's name ever since.

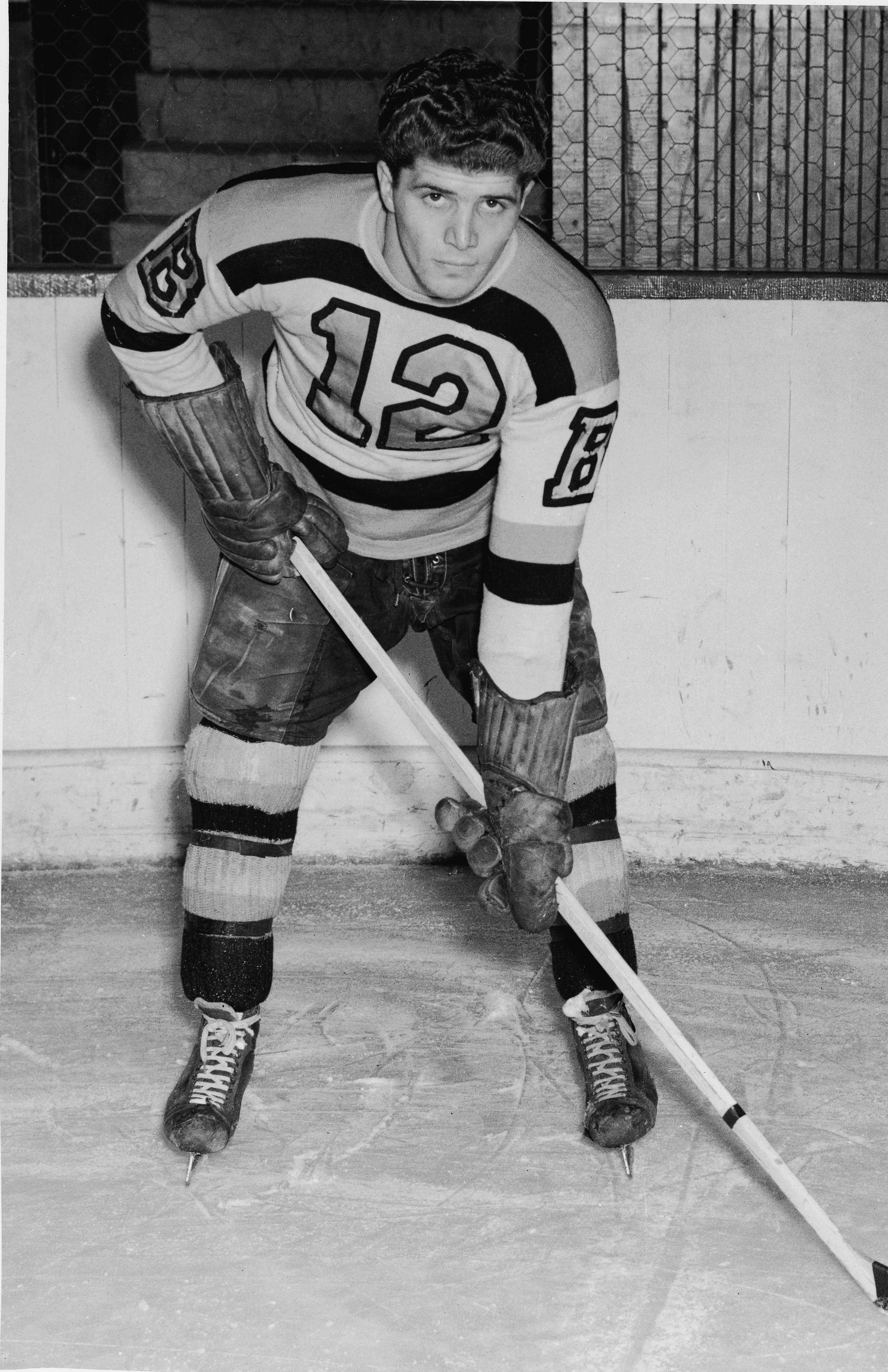

Initially, Gallinger had all the hallmarks of a hero. When he first laced up his skates and took the ice for the Bruins in 1942, he was the youngest player to ever skate in the NHL at 17 years, 6 months, and 22 days old. By the end of that season, he placed third in voting for the Calder Trophy as the league's best rookie. During the Bruins' playoff run, his overtime goal against the Montreal Canadiens earned him the record for youngest player ever to score in overtime during the NHL playoffs, a distinction he still holds.

Gallinger's hockey career was interrupted in 1944 when he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force and spent 22 months in military service, but he returned to the Bruins in 1945 and led the team in scoring.

That positive trajectory all came crashing down a few short years later when Gallinger played a role in a scheme that saw him bet on NHL games and also bet against his own team. In the fall of 1947, Taylor approached Gallinger with an offer: Taylor had a contact who'd guarantee 2-1 odds on any bet placed through him; in exchange, the two players needed to supply their contact with insider info on Bruins injuries and other intelligence not available to the public. The only catch: to prove the quality of their information, Gallinger and Taylor had to place bets on the Bruins themselves, even if it meant they'd be betting on the Bruins to lose.

It wasn't long before the plot was uncovered and Gallinger was suspended.

"I don't know that he would have turned out any differently. If he'd been given another chance on a reinstatement, he may have just gone right back and offended again. He was a confident, cocky person and it was hard to tell him just about anything," says Addis, the past president of the Society for International Hockey Research who's spent years digging deeper into Gallinger's fate.

Despite what he uncovered, Addis believes the NHL's handling of Gallinger's case was heavy-handed, and that the story is particularly relevant in today's sports betting environment. "The more I study this, the more I believe that Gallinger himself was predisposed to gambling. The higher the stakes, the better," he says. "It's easy to advocate for the hero; it's a little more difficult to suggest that someone who had a lot of trouble perhaps deserved a little bit more consideration."

theScore recently talked with Addis about Gallinger's story. (The interview's been edited for length and clarity.)

theScore: Out of all the stories you've come across in your work as a hockey historian, why did you write a book about this one?

Addis: I knew the subject. I knew Don Gallinger myself. I lived in a little town called Port Colborne in Ontario. And it was there that Gallinger played his minor hockey and then graduated to the NHL.

Gallinger was a larger-than-life story: his rocket ascent into the National Hockey League at the age of 17, right out of Junior B hockey, had never been done before. But you hear everything about a person in a small community. Some people said he was reckless, some people called him an idiot. Some people called him worse than that. This was all mostly based on the fact that he was suspended. But those that really knew him well spoke of him with a degree of respect, because they knew just how incredibly talented he was. And secondly, they knew all that he'd lost when he was suspended from the NHL.

The story of Don Gallinger was largely written by the NHL: he was a cheat and he got exactly what he deserved. But the story is much more nuanced and complex than that.

Q: Can you describe the type of player Gallinger was?

First of all, he was big: 6-foot-1. Especially hockey players in the '40s and '50s - there weren't many guys that were six-foot. He was incredibly fast. A heck of a playmaker, and probably one of the biggest assets that he possessed: he was supremely confident.

He was absolutely fearless and demonstrated that fearlessness right from the get-go, when he was at training camp with the Bruins at 17.

Q: Gallinger entered the league during World War II, when many players were serving in the armed forces overseas. How did he stack up against those who returned to the NHL after the war?

He made the club and he did extremely well in his first year. He scored an overtime goal in the Stanley Cup playoffs, Game 1 against Montreal. The following year, his season was interrupted when he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force. He enlisted in the service of his king and country and came back after the war in the '45-46 season and led the team in scoring.

This was after all of the greats of the team had returned from war service themselves. It was thought that these young players that came on during wartime as basically wartime substitutes wouldn't be able to make the grade when the other athletes returned from their war service, but Gallinger stuck with it, hung in there, and he not only stayed with the team, he led them in scoring.

Q: When did Gallinger get into betting on NHL games?

In September of 1947, his best friend and teammate Bep Guidolin was traded to the Detroit Red Wings for a gentleman by the name of Billy Taylor. Now, Taylor had come up through the Toronto Maple Leafs system and had been shipped off to Detroit, where he led them in scoring the year before. Almost out of the blue he was traded to the Bruins and moved right into the same rooming house as Gallinger. Taylor was 28 and Gallinger was 22 and somewhat impressionable.

Taylor had a reputation for being a gambler and Gallinger liked that about him and aspired to be the same thing. He basically was taken into Taylor's confidence, which included being introduced to one of Taylor's contacts from Detroit, James Tamer, who was a convicted bank robber out on parole. Tamer had organized a gambling syndicate in Detroit through a couple of restaurants that he owned, and some other entities.

Q: In order for the scheme to work, there were instances where Gallinger and Taylor had to bet against themselves and the Bruins. Was there any indication they wrestled with the ethics of that?

Gallinger and I never spoke about that directly before his death in 2000. He left some manuscript materials that suggested they weren't overly concerned about it. I was able to establish in the Boston media itself (that) there were a number of columns that said there's no problem with betting on yourself or betting on your own team. In fact, it was considered a mark of confidence on the part of an athlete.

Gambling was enforced at various levels in the various NHL cities of the day, and some police departments were a little more lenient, others were a little more heavy-handed. Certainly, in Boston, it wasn't considered a big deal.

Sports reporters were always complaining about gamblers basically hawking their wares at Fenway Park in Boston during baseball games and at the Boston Garden during Bruins games. So, I think you could say it was an accepted part of the sports culture. But as far as betting against your own team, I think everyone understood that would be considered crossing the line.

Q: How did the whole house of cards come crashing down on Gallinger?

In the fall of 1947, Taylor and Gallinger, then teammates on the Bruins, set up an arrangement whereby Taylor would place the bets for or against (the team). He would make those bets directly with Tamer in Detroit. So, he was the pipeline.

Early in February 1948, Taylor was traded to the New York Rangers, so that direct contact with Detroit no longer existed. But the next game that Boston played in Detroit, after the game in a restaurant, Tamer approached Gallinger and personally gave him his phone number and said, "Don't worry, nobody answers this phone but me."

With that number, a couple of weeks later, while the team was in Chicago, Gallinger placed the bet through Tamer, and - on the one and only time that Gallinger placed the bet - the Detroit police had Tamer's phone wiretapped.

Although it was never proven it was Gallinger on the other end of the line - in other words, he never identified himself, said his name, or gave any clue as to his identity - (NHL) president Clarence Campbell was so concerned about removing any specter of betting out of the game that he pursued a private investigation on behalf of the league.

The Detroit police and the governor of Michigan had absolutely no interest in prosecuting charges. As far as they were concerned, all the evidence against Gallinger and Taylor was entirely circumstantial, it would never stand up in the court of law. But of course, the NHL had no interest in taking the case to court. They were just going to keep these two individuals out of the game for as long as possible, and therefore, they were suspended.

Q: What was happening culturally at the time that made gambling such an important issue for the league?

It was postwar America and they were perhaps hyper-concerned with guaranteeing that the American way of life was preserved. This is what they fought the war for. This is why thousands of men had died overseas: to preserve the American perception of the good life and life in a democracy. Gambling had no place in that life.

It should be noted that the previous sentence or suspension for gambling in the NHL in Gallinger's time was to a gentleman by the name of Babe Pratt, who was at that time a defenseman for the Maple Leafs. He was suspended for betting on NHL games, though with a different NHL president, but he was suspended. He got six games and (a) nine days suspension, something like that. You might think, a year and a half later, Gallinger might reasonably expect to maybe get the rest of the season or the playoffs, something of that nature, maybe one season. But to have been suspended for more than 20 years, I think by anybody's definition, appears to have been draconian.

Q: Can you talk about the fallout in Gallinger's life after he was suspended?

It was immediate. He was suspended in March of 1948. Previous to that, in addition to playing hockey, he had tryouts with the Boston Red Sox and with the Boston Braves, as well as the Philadelphia Athletics, all Major League Baseball teams. They all wanted to sign him to minor-league contracts but Gallinger wasn't interested because he was making major-league money in hockey. That gives you a sense of the kind of athlete he was.

Taylor was suspended for life immediately but Gallinger's was an indefinite suspension until further investigation, so he was kind of in limbo. He thought naturally, 'Alright, if I can't play hockey, I'll play baseball.' But he found out pretty quickly that those offers dried up. Basically, he'd become a bit of a pariah. Nobody wanted to touch him with a 10-foot pole. So, he didn't know what he was going to do.

(Gallinger was eventually invited to play for and manage the Waterloo Tigers of the Intercounty Baseball League, a regional semipro league in southwestern Ontario.)

During that time, he appealed to the NHL for reinstatement. He had an in-person appeal with a lawyer present and they were almost certain to have had the suspension lifted had a vote been taken. But Campbell intervened when the directors looked like they were going to vote in favor of reinstating Gallinger and his reinstatement was squashed.

In 1963, Scott Young, the father of famous Canadian musician Neil Young, was writing for The Globe and Mail and ran a three-part series basically advocating for Gallinger and saying it was time his suspension be lifted. It was 15 years by that time, and still, the NHL hadn't budged.

It wasn't until 1970, after some inner turmoil in the NHL, that the suspension was lifted. Conn Smythe, who was by then the retired manager and owner of the Maple Leafs, (saw) his own son was in trouble with the police and it looked like he might be charged, in terms of charges relating to the shareholders of Maple Leaf Gardens. Smythe's son passed away before the charges were laid. Consequently, it was thought that Smythe, seeing what had happened to his own son, called the NHL office and said it's time to clear Gallinger and Taylor.

The suspension had gone on for 22 years. Gallinger had been married, had four children, and his marriage broke up as a result of it. He tried many different businesses. But always, the same thing happened when push came to shove: he just didn't have the capital and resources to carry through with them. He was considered somewhat of an outsider and an untouchable based on his reputation from the charges in the NHL. Eventually, he moved to California. No one knew where he was when the NHL tried to reinstate him. A letter was sent to one of his old employers in the hope they might be able to track him down. He was applying for a job in the classifieds in L.A. The person who he was calling said, 'Are you the same Don Gallinger who just had his suspension lifted by the NHL?' First time he'd heard of it.

Q: Why is Gallinger's story relevant today?

I think it's a story worth telling especially because of the prevalence of access to online gambling. It tells the story of someone who was hurt by their addiction to betting on sports.

I think one of the primary concerns is not the fact that there is gambling and sports betting - of course, that's part of our contemporary culture, that's never going to go away. I think the lesson is that, despite the broad spectrum of the population that appears to be interested in sports betting, we shouldn't lose sight of the fact that there are people who fall through the cracks and fall by the wayside. And consequently, some considerations should be made for them.

Jolene Latimer is a features writer at theScore.