Gerry McNamara finds his place again in Maple Leafs lore

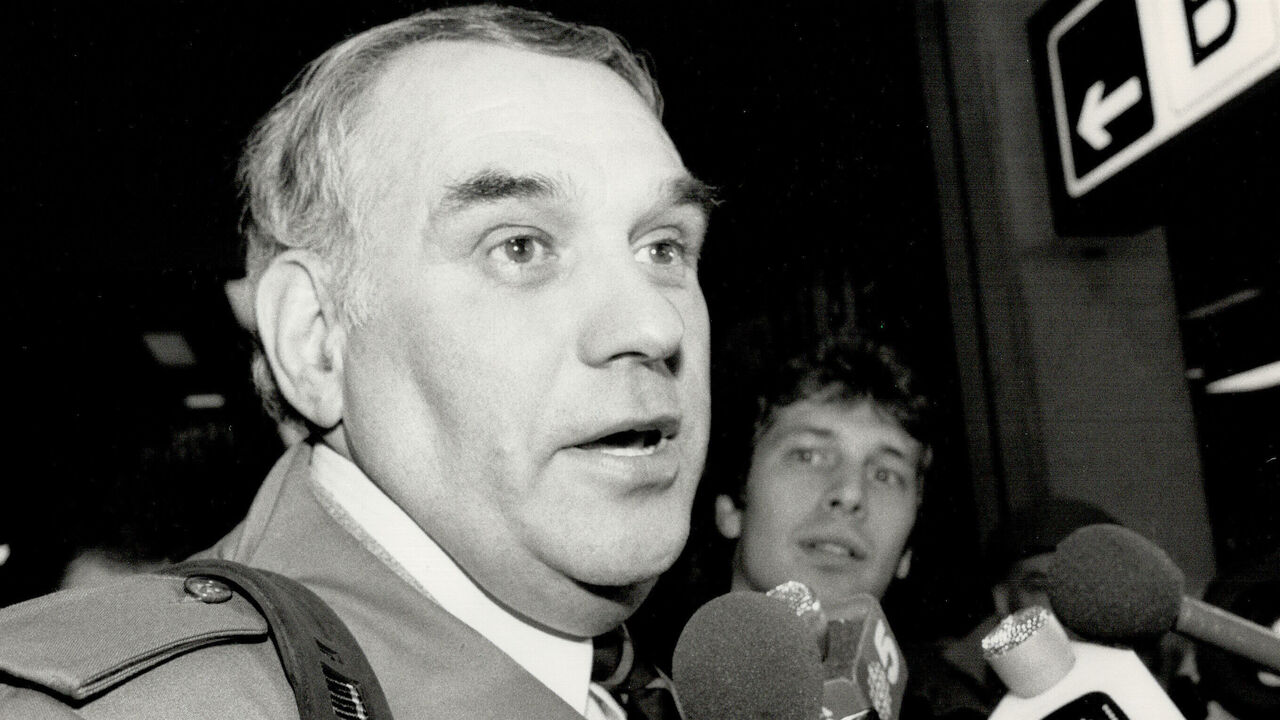

He instinctively knew the warning was true. It was Feb. 7, 1988, and Gerry McNamara, then general manager of the Maple Leafs, was in Hartford on the last stop of a three-game road trip when he received an urgent phone call. On the other end of the line was the Toronto Star's Milt Dunnell with a scoop, and not a good one.

"Gerry, you're going to be fired."

McNamara had been with the Leafs since 1960, beginning as a 26-year-old backup goalie before ascending the organization's scouting ranks. By 1988 he'd been general manager for seven years, but at the time was embroiled in a public battle with coach John Brophy; the frustrations were coming to a head.

"I was really upset," the 90-year-old McNamara remembers. "I knew the players hated the coach and I couldn't get rid of him. I kept going in to see Mr. Ballard and he said, 'You better get to like him, he's the coach.'"

Dunnell's information proved accurate. Hours later, Leafs owner Harold Ballard called McNamara at the team hotel to deliver the official blow. "Finally, he fired me. He didn't fire the coach," McNamara says.

Brophy wouldn't last much longer - he was replaced midway through the 1988-89 season - but that was hardly consolation for McNamara. Everyone around him could sense the depression he fell into after losing the GM job. Even his dog, Puck 2, an offspring of Ballard's dog Puck. "I came home, I sat in my chair and Puck 2 watched me, and he knew I wasn't myself," McNamara says.

His abrupt dismissal from the organization meant losing his job but also losing his identity. "The golf course I belonged to saved my life. I would go every day and play for hours," he says. "They knew I was hurting, and they didn't add to it. That's how I got through it."

McNamara went back to scouting for a few years, even earning a Stanley Cup ring with the 1989 Calgary Flames, but had trouble landing a permanent hockey job. He eventually distanced himself from the sport almost completely, only watching junior games his nephew played in. "When you lose something, it makes you feel bad," McNamara says. "I didn't want to torture myself, so I just forgot about it all."

The grudge against hockey persisted for decades. "I didn't care about the NHL," he says. Recently, that changed.

Building the game

McNamara was involved in the Leafs community for most of his life, starting in childhood as a fan. He still remembers getting a last-minute ticket from a St. Michael's Majors teammate to attend Game 5 of the Stanley Cup Final in 1951 when he was 16. It turned out to be a magical night at Maple Leaf Gardens, when Bill Barilko scored his famous overtime goal.

As an adult, McNamara played seven games in net for the Leafs over two seasons separated by nine years; with only six teams in the league until 1967, goalie jobs were highly competitive and having bad knees didn't help. After his playing career was over, he switched to scouting and then management, until he was fired at age 54.

To say McNamara made his mark on the Leafs organization as a scout is obscuring the success of his early career, which can be credited with having a role in shaping today's NHL.

"The biggest thing was going to Europe and getting (Borje) Salming and (Inge) Hammarstrom," hockey historian Paul Patskou says. "It turned the Leafs around. And it opened up the doors to more Europeans."

The story of finding Salming remains one of McNamara's favorites to tell. "It was a miracle," he says.

McNamara initially flew to Sweden in late 1972 to scout a goalie, who was injured throughout McNamara's trip. Instead, McNamara traveled over two hours from Stockholm to the town of Gavle, where the Barrie Flyers, an Ontario senior A team McNamara played against in the late 1960s, were facing off against a Swedish Division I team.

"I go to the game and it's blood and thunder," McNamara says. "They were spearing and slashing. The Canadian guys were thinking they'd run these guys off the rink. But Borje, he didn't back off.

"I said to myself, 'This guy's got moves I've never seen in hockey.' We didn't have anybody like that. We had to have him."

What happened next became part of Leafs lore, immortalized in the 2023 limited series "Borje," about Salming's life. Actor Jason Priestley played McNamara, while McNama himself was an advisor and appeared in a cameo role.

"With about two and a half minutes left, Borje got thrown out of the game," McNamara says. "I followed him back to the door of the dressing room. They went inside. I knocked on the door. The trainer came to the door, and I could see Borje sitting on the bench. I said I wanted to speak to him."

After talking his way into the dressing room, McNamara offered Salming an opportunity to play for the Maple Leafs. Salming didn't speak a lot of English, so they agreed to use Hammarstrom, who McNamara also wanted to sign, as an interpreter.

"I waited for the team to come off the ice, grabbed Inge, and he agreed to give me a call after the game. They called me at one in the morning." By the end of that call, McNamara had recruited one of the greatest defensemen to play the game.

There was only one other European in the NHL before Salming made his debut with the Leafs in 1973-74. The following year, Europe became the hot-spot destination for NHL scouts looking for fresh talent.

"Gerry knew talent," Patskou says. "It was probably pretty obvious that these guys were that good - but there was no one else there. Gerry went into the dressing room. He was so determined to get these guys and put them on a negotiation list. He was a hero for that. The next year the place was crawling with scouts because they then knew what was over there. He opened that door."

The influx of Europeans indeed changed the game and the league. Salming was the first European-born NHLer to play 1,000 games, and in 1996 became the first born-and-raised European in the Hockey Hall of Fame. Yet Salming wasn't the only significant contribution McNamara made to the Leafs during his tenure. As general manager, he used the No. 1 pick in the 1985 draft to select Wendel Clark.

"The scouts wanted me to take Craig Simpson. I saw Clark play, and I really liked him, but he was a defenseman. But he was up the ice all night," McNamara says. "I said to myself, 'I like this guy. I think he's going to be a power forward. He's not going to play defense for us.'"

McNamara followed his instincts. "I listened to what the scouts had to say, then I left the meeting. I'd made up my mind who I was going to take, but I never said anything," he says. "The chief scout came to me privately and said, 'The consensus is we're going to take Simpson.'"

The consensus didn't matter much. "It's my name. We're taking Clark," he says. Toronto indeed drafted Clark, who converted to forward, earned 330 goals and 564 points in 793 regular-season games over his 15-year career, and became one of the most popular modern-era Leafs.

Coming back into the fold

Patskou, who owns one of the world's largest private collections of archival hockey footage, is active in the hockey alumni community, organizing monthly alumni lunches in the Toronto area, producing the "Hockey Time Machine" podcast, and weekly Zoom calls for insiders interested in hockey history. McNamara was long on his list of alumni to engage with, but it wasn't easy at first.

"He didn't want to come to the lunches," Patskou remembers. "He was treated very poorly by the media when he was fired. And he probably took that to heart, and he just didn't want anything to do with it."

But Patskou eventually won McNamara over, even producing a video tribute for him at one of the alumni lunches. During the pandemic, McNamara found community by participating in the weekly Zoom calls. When the group later began meeting in person, McNamara was more comfortable joining the conversation.

"I got him up to talk in front of everyone and even interviewed him," Patskou says. "He was having a great time talking about it. And he started to really come out of his shell, and he started looking forward to everything."

McNamara now connects with the group of hockey history lovers weekly on Zoom, in addition to attending the monthly alumni lunches and other hockey history events, like the Sports Card Expo in Toronto earlier this season. He regaled visitors to the "Hockey Time Machine" booth with stories of his career.

"It completely changed my life," McNamara said about recent developments on one of the Zoom calls. "This 'Hockey Time Machine,' these guys who are on now, who are on every week, have become great friends of mine - I'd go to war with them. That's how much I feel about them. It's been a revelation to me because I was in hibernation for 20 years, where I hadn't heard from anybody. All of a sudden, this thing opened up."

"It 100% is the best thing that ever happened to him," his son David says. "Now when people ask, 'Hey, how's your dad?' I'm like, well, he does podcasts. He's 90 years old and doing podcasts!' Every night when I call, he answers and says he can't talk because he's doing an interview. When I listen to him, he's funny. He's got a quick wit. His stories are interesting. My friends are glued to listening to him."

Always a Maple Leaf

Still, there was one thing missing for McNamara: reconciling with the Leafs organization.

"Every time we tell the Salming story, Gerry's role in it has always been a part of it," says Mike Ferriman, the Leafs' director of alumni relations. "That part with Gerry going down to the dressing room and starting that conversation that eventually brought him here to Toronto - it's an amazing story."

But the Leafs had yet to reach out to McNamara personally. It was something Maple Leafs president Brendan Shanahan wanted to change. "Ever since I've come here, one of my focuses has been re-engaging with the alumni," Shanahan says. "I was trying to look a little bit deeper and say: what about coaches and managers? It's a little bit harder with coaches, because it's such a transient position in hockey. But managers tend to remain in the community. So, I was asking about who was still around, and that's when Gerry came to mind.

"I didn't even realize some of the feelings he was harboring, but he's a pretty honest person and tells you exactly what he thinks. I was glad that he did, because I had no idea that he had some hurt feelings still. I felt a lot of empathy for him, and I took it very seriously. My regret is that I didn't know how he was feeling sooner," Shanahan says. "Being scrutinized is part of the business we all accept, but we all handle and absorb it differently."

Shanahan made personal efforts to engage McNamara, inviting him to his annual golf tournament as his guest and encouraging him to attend Leafs games in the alumni box. "There's a saying in hockey that we like to hot stove it up. And Gerry's like that. He likes to be around, and the guys love to hear his stories," he says. "I think the first time he came around he felt he had to explain some things - why a certain trade happened or didn't happen. The people around him were sort of like, you've got nothing to explain. We're happy to have you back.

"The contributions that he made - you're talking about two of the most iconic Maple Leafs ever. It's pretty remarkable that he was able to see those things and get them done."

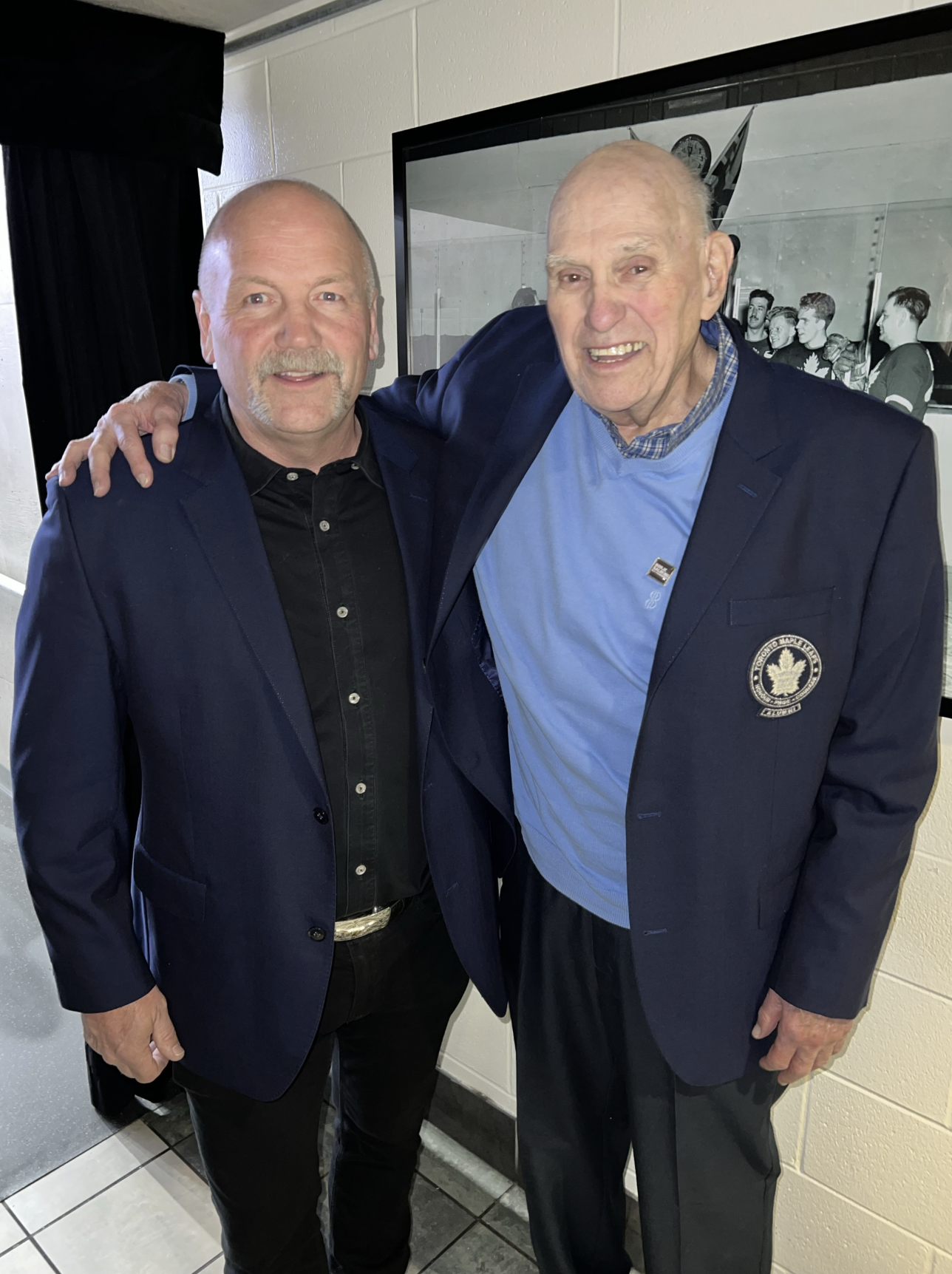

Shanahan also worked with Ferriman to have McNamara honored at center ice in Toronto with an alumni jacket, which was presented to McNamara by Clark last season in front of a full house at Scotiabank Arena.

"It was five minutes before the first period was over and Ferriman took me to the alumni lounge. Then he said, 'Stop here.' I stopped," McNamara remembers. "My back was against the wall. All of a sudden, a camera man was there. My picture appeared on the jumbotron. I didn't know they were doing this. And Clark came over with a blazer. It was an exciting night. It felt pretty good."

David McNamara recalls feeling overwhelmed when his dad arrived at his house the next day for a family dinner. "He wore his jacket to dinner and he was as proud as anything," David says. "I got emotional when he came in, and I get emotional now thinking about it."

Losing the hockey community is often painful for many alumni, regardless of the circumstances. "When you've grown up in hockey, whether you're a player or management, your whole life is about being part of a team. When you lose that, it's like a family has been ripped away," Shanahan says.

"Gerry made a comment to me after a game he attended that really stuck with me. He said that it had changed his life. It made me very happy, but it also made me think, why didn't I reach out sooner?" Shanahan says.

For McNamara, the journey back to hockey was a long time coming, but in the end felt as natural as coming home.

"It feels like I have a team again."

Jolene Latimer is a features writer for theScore