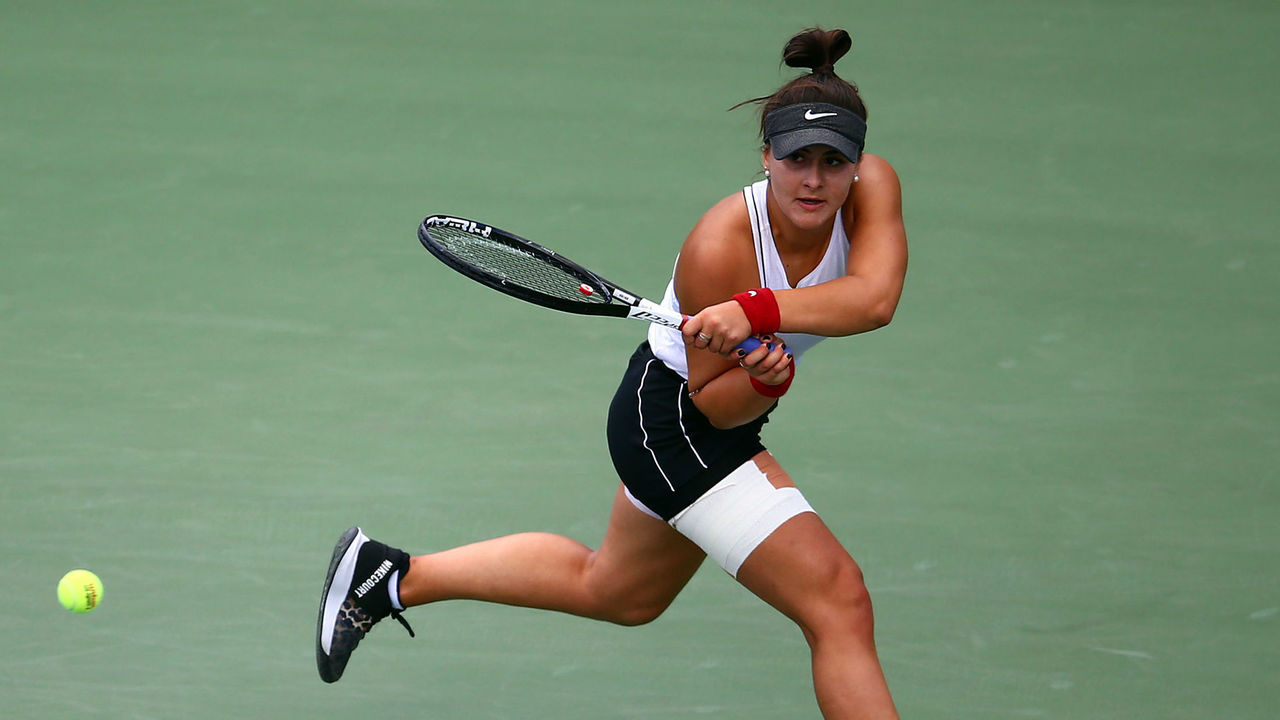

Bianca Andreescu's great tennis adventure is just beginning

Bianca Andreescu has a recurring nightmare. In it, she's transported back to January 2018, back to her first-round Australian Open qualifying match against Alexandra Dulgheru, which she lost 6-1, 6-1.

"That year, I was going through a rough time with my tennis, and a lot of things off the court, too," Andreescu told theScore a day after claiming the Rogers Cup title on home soil.

"I played the worst match of my entire life. Like, I forgot how to hit a tennis ball. And ever since that day, I've been getting nightmares. Of me not knowing how to play tennis. And sometimes when I step on court, that fear is in the back of my head. I have to realize I'm not the same person or the same tennis player I was back then. But there's always that fear."

It turns out Andreescu wasn't being entirely literal when she told reporters in Toronto last week that she's fearless on the court. But the 19-year-old wunderkind does seem to have a preternatural capacity to deal with whatever fear creeps into her mind. Watching her play this year, you'd never guess she was carrying an ounce of apprehension.

In 2019, she's compiled a 38-4 record, which includes going 15-3 in three-setters and 9-1 after dropping the first set. She's played seven matches against top-10 players, winning all seven. She's made a habit of battling back from the brink and refusing to blink in big moments, demonstrating a mental fortitude that belies her youth and inexperience.

Tennis can feel almost like an administrative task in the way it constantly forces you to manage things. Manage risk, manage nerves, manage energy, emotion, tactics, and pain. In the end, no one is impervious to the chest-tightening knowledge that you can't run out the clock, that there's no one to defer to, and that you alone have to close. It can exact an immense psychological toll.

Andreescu, who practices creative visualization, explains that she's able to manage her most stressful on-court moments in large part because she plays them out in her mind ahead of time. Familiarity is a great antidote to fear, so she tries to make those frightening situations seem as familiar as possible. She can arrive at a new challenge and feel like she's faced it already.

"I'll sometimes visualize myself in situations where I need to figure out something in order to come back," she said. "Or, I'll visualize myself doing really well and just keeping it up. So when I'm in the match, it's … I wouldn't say easy, but since I've been working on it for so long, I have this mental switch where I can just get into my zone.

"I basically try to visualize every scenario that can happen in a match. I don't do it all at one time. One day I'll do this, one day I'll do that. It's like, 20 minutes of … ." She stops herself. "I don't want to go into too much detail about it, because I think that's one of my secrets."

So often, we try to boil the margins of competition down to "who wants it more," which is one of the most disingenuous cliches in sports. It makes more sense to take for granted that both competitors "want it" equally, but that they go about dealing with that desire in their own ways. More than how badly she wants to win, it's Andreescu's ability to contain her desire - to not let it consume her in the highest-leverage moments - that has brought her so much early success.

One thing you realize when you talk to Andreescu is that she has an intensely analytical brain. She tries to sponge up as much knowledge and information as possible, whether it's from a book, from a docuseries like "Explained," or from a personal interaction.

"I love to read. I love to research on my own. I just love to learn, learn, learn," Andreescu said.

She added: "I love to read self-help books about the mind, how the mind works. Because the mind is an incredible tool. You basically can create your own reality with your mind."

On a tennis court, thinking too much can be your downfall, but Andreescu has seemingly figured out how to channel her thoughts in productive ways. She keeps a journal, sees a psychologist, and obsesses about preparation. She goes into every match with a game plan, drafted in consultation with coach Sylvain Bruneau and a tennis analytics platform that feeds them data on her opponents' tendencies. That level of preparation helps explain her precocious tennis IQ.

"She's an old soul," Serena Williams said shortly after retiring from the Rogers Cup final to hand Andreescu her second Premier-level title of 2019, and the first championship in half a century for a homegrown player at the prestigious Canadian tournament.

"She definitely doesn't seem like a 19-year-old in her words, on court and her game, her attitude, her actions," Williams added.

Andreescu began the year ranked 178th in the world after registering zero tour-level wins in 2018 while failing to qualify for a Grand Slam main draw. She's since climbed to No. 14, won the two biggest singles titles in Canadian tennis history, and earned the respect of the greatest player of all time.

Is that what creating your own reality looks like?

By her own estimation, Andreescu is a thrill seeker.

"I love to take risks," she said, before quickly clarifying, "to a certain point. Because I've taken risks that have plunged me downward. I'm never making that same mistake." She declined to elaborate.

Andreescu told me something similar back in February, shortly after her finals run in Auckland that kick-started this whole improbable surge. "I'm a really adventurous person," she said back then. "If someone would say, 'OK, let's go bungee jumping,' I'd definitely go. Or like, jumping out of a plane, I'll definitely do that."

When I asked what the most adventurous thing she'd done was, she laughed. "I've, uh, ziplined. I … rode in a helicopter once?" The point, she explained, was that she was open to doing pretty much anything.

Her tennis bears that out. Andreescu's play really does have an adventurous quality to it: daring, explorative, unpredictable, different. She's long said that she looks up to and emulates Simona Halep, with whom she shares Romanian roots, but while you can certainly see shades of Halep in her game - the swift horizontal movements, the prescient returning instincts, the ability to turn defense to offense on a dime - Andreescu hits with far more variety, and is a bit keener on playing inside the baseline and approaching the net. (She also admires Kim Clijsters, who represents a more apt stylistic analog.)

Really, nobody on tour plays quite like Andreescu, a tennis chameleon with an uncanny ability to exploit exactly what her opponent gives her. "Counter-puncher" doesn't quite do her justice, because she can throw instigative haymakers of her own. (For instance, she compiled 44 winners to only 16 for Angelique Kerber in the Indian Wells final in March.) Like a Looney Tunes character whose pockets contain a whole universe of props, Andreescu has an inexhaustible stockpile of shots in her bag that she can conjure up on a whim.

She cranks runaround forehands that she can take inside-in or inside-out, keeping you in suspense until the moment she strikes the ball. She opens up the court with short angles. She has magnificent touch on her drop shots. She gets way down low to hit crouching groundstrokes (a la Kerber or Agnieszka Radwanska) that allow her to hold the baseline, absorb her opponent's power, and dish it right back.

Andreescu can also get weird, and more than a little junky. She likes to hit a slice forehand approach that skids low and wide as she charges the net. She isn't too proud to loft the odd moonball to change the pace and muck up her opponent's rhythm - though she refuses to call it that. "I would say more of a deep, effective, high ball," she described it after last week's first-round match against fellow Canadian Eugenie Bouchard, in which that shot had proved particularly useful. "Sounds better."

From shot to shot, she'll vary the pace, the spin, and the height. She'll sky one of those deep, effective, high balls, and on the next one flatten it right out with a screamer down the line. As Kiki Bertens succinctly put it after falling to Andreescu in the third round of the Rogers Cup, "She can do everything with the ball."

The times she's seemed to struggle most have been against opponents who can use her own rhythm-busting tactics against her, as Daria Kasatkina did in the second round in Toronto. Boxing her own shadow seemed to make Andreescu uncomfortable.

"I was talking to my coach after the match, and I told him, 'Now I know how people feel when they play me,'" she said with a chuckle after the grueling three-set win. "It wasn't easy."

That subtle humblebrag aside, Andreescu doesn't make a habit of pumping her own tires. If anything, her conception of her own ability has seemed to lag behind reality. When she scored a landmark win over Kristina Mladenovic at her first-ever tour-level event in 2017, she said, "To be honest, I didn't think I could win that match." After beating Venus Williams in Auckland this year, she said it felt like she'd done "the impossible." And after winning the title at Indian Wells in March, she admitted that going into the tournament she hadn't believed she could do so. She also said multiple times that she came into the Rogers Cup with zero expectations. She still seems genuinely surprised by her success.

"I'm definitely surprising myself," Andreescu said after beating Sofia Kenin to reach the final in Toronto. "I don't realize the things I can do on the court. My coach is always telling me that I'm a champion within, but I guess - I don't know, maybe I am starting to realize that slowly. But at this point, I don't want to take anything for granted. I mean, there's going to be weeks where you're going to lose. Right now, I'm doing pretty well."

While she justifiably harps on the mental aspect of her game, Andreescu hasn't been quite as resilient on the physical side. She's already dealt with a handful of setbacks (though she prefers not to call them that) in her young career, including a back ailment last year and a shoulder injury this season that led to her playing just one match in the five months between late March and her arrival at the Rogers Cup.

As difficult as it was, that long layoff appears to have served her well. Andreescu came home to Toronto, spent time with family and friends, went to a bunch of Raptors games, and reimagined her diet and fitness regimen. She started working with a physiotherapist full time, which she called "one of the best investments I've made." (An investment surely made more palatable by the $2.2 million in prize money she's pulled in this year - about $2 million more than she'd previously made in her career.)

"I'm actually happy I did have a little break, because I played so much at the beginning of the year," she said. "It gave me time to reflect on everything. It's nice to just get out of the bubble of being a professional athlete and traveling around the world. It helps me stay grounded."

The challenge for Andreescu now that she's back and rolling again, is to navigate the push-and-pull between her will to compete and the need to listen to her body. It's a delicate balance, as she's discovered. You have to pace yourself and make sure you don't break down, but you inevitably weigh that caution against your desire to challenge yourself, be resilient, and prove that you can play through pain. It's your heart at war with the rest of your body. Succumb to the pain, and you might earn a reputation for being fragile, or get called names by an opponent. Push too hard, as Andreescu did by playing the Premier event in Miami after fighting through injuries to win at Indian Wells, and you might cost yourself five months.

In Toronto, she picked up a groin injury in her quarterfinal match against Karolina Pliskova, but insists she never had any intention of pulling the plug - not at such an important stage of such an important tournament.

"At this point, I know when something's bad and when something's okay to push through," Andreescu said. "But even when it's something bad, it's the toughest decision to tell yourself you can't play, like Serena had to do in the finals.

"I'm the most impatient person at times. But at my age, I want to try to have the longest career possible, so even if it's not the decision I want to make, I know I have to make the right one, or at least try to. I can't just think about now; I have to think about the long term."

We always romanticize youth in pro sports. Part of what makes the whole enterprise magnetic is that it provides such a tangible manifestation of individual progress, and young athletes leave the most room for our imagination. They appeal to our obsession with extrapolative projection. We tend to assume success will beget more success, which often ultimately proves to be a letdown.

"When you're that young, everything is so fun," Williams said before facing Andreescu in the Toronto final. "I mean, everything is still fun. But (at that age) everything is new and everything is a different challenge and there's not a ton of pressure."

After losing to 20-year-old eventual champion Jelena Ostapenko at the 2017 French Open, Timea Bacsinszky posited something similar: "She's 20 - not afraid of anything. She doesn't measure maybe what she's doing right now. She probably doesn't care. She's just hitting it the same."

But a handful of those audacious young hitters have recently grown disillusioned when faced with the heightened expectations they've created for themselves. Some have admitted to losing their love of the sport shortly after their greatest triumphs, when suddenly it's less about having fun than meeting those expectations.

Naomi Osaka won back-to-back Grand Slam tournaments at the age of 20, the most recent coming at this year's Australian Open. But before the start of the hardcourt swing, she wrote: "I can honestly reflect and say I probably haven't had fun playing tennis since Australia."

Denis Shapovalov hasn't come close to winning a Slam, but he exploded onto the scene as an 18-year-old with a run he hasn't quite been able to replicate. Two summers later, he told reporters: "I've been missing something else, something from inside. For me, it was the passion for the sport."

Andreescu came into 2019 with the modest goal of earning direct entry into the French Open. Now, she's harboring the objectives of cracking the top 10 and qualifying for the WTA Finals. (Last week's win put her into the eighth and final qualifying spot for now.) But she's adamant that she won't chafe under the yoke of her new reality, or join the ranks of the jaded.

"Definitely not," she said. "It's all heart when I'm out there. I'm dedicated 100 percent to this sport."

It's easy to believe her. She seems entirely self-possessed, exuding nary a shred of existential angst or doubt about the precarious, pitfall-laden path she's decided to walk.

When she does eventually slump - which, at some point, she will - maintaining her sense of equilibrium and perspective will be the real test. Though she considers herself a perfectionist, Andreescu doesn't see internal pressure being an issue. The external pressure, she acknowledges, can be a different story.

"It's hard not to focus on that because you don't only want to do it for yourself when you're out there, you want to do it for everyone who's supported you and everyone who's been with you since Day 1," she said.

"So sometimes when I lose, or when I don't put in my best performance, I tend to look at (the external) aspect of things. Sometimes it's not easy. But everyone's human, everyone loses, everyone plays a shitty match here or there. Right now I'm trying to focus on the positive."

Andreescu may have gone into Rogers Cup without expectations, but when it was over and she was standing at the final ceremony, delivering a championship speech, at the arena where she trains, 15 minutes from where she grew up, she allowed herself to get swept up in a dream of the future.

"This," she said, holding up her trophy, "is just the beginning."

HEADLINES

- Serena is soon eligible for tennis comeback. It's unclear if she'll do it

- Understated triumph: Rybakina wins Australian Open with calm precision

- Rybakina takes down No. 1 Sabalenka to win Aussie Open title

- Mertens and Zhang, Harrison and Skupski win Aussie Open doubles titles

- Gadecki, Peers repeat as Australian Open mixed doubles champions