How would an extra foot from mound to plate affect baseball's current trends?

Major League Baseball will test the most radical potential change to its playing dimensions in more than a century this summer on minor-league fields in small towns like Gastonia, North Carolina; Lexington, Kentucky; and Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

MLB announced Wednesday it will partner with the independent Atlantic League to conduct a couple of experiments in the coming months. They include two changes designed as possible remedies to unrelenting trends baseball views as bad for business - trends it has failed to reverse organically.

One of the two rules that'll be in place in the Atlantic League is dubbed the "double hook." The rule ties the designated hitter's in-game existence to the starting pitcher. When a starting pitcher leaves a game, that team loses its DH. MLB hopes the rule will incentivize increasing the length of starting pitching appearances, which have been decreasing. The rule would also likely diminish the use of openers, the practice of starting games with a relief pitcher who makes a short outing to serve a variety of strategic purposes.

The other rule change - the more dramatic one - is moving the pitching rubber from 60 feet and 6 inches away from the plate, a distance encoded since 1893, to 61 feet and 6 inches. Atlantic League teams will play the season's first half at the traditional distance, then use the longer distance, and MLB will compare the results.

These radical experiments are being tried because of how the game's evolved in recent years, resulting in fewer balls in play. MLB's concerned about what the increases in strikeouts and pitching changes mean for interest in watching the sport, in attracting and retaining customers.

Now that baseball is considering more radical experiments - and could potentially unilaterally implement them before a new CBA is signed - we're curious: what kind of effect might they have?

MLB was originally going to experiment with pushing the mound back to 62 feet and 6 inches last year in the second half of the Atlantic League season but the pandemic derailed those plans. The league said in its release that moving the mound back 1 foot is "the minimum interval needed to evaluate a change in mound distance."

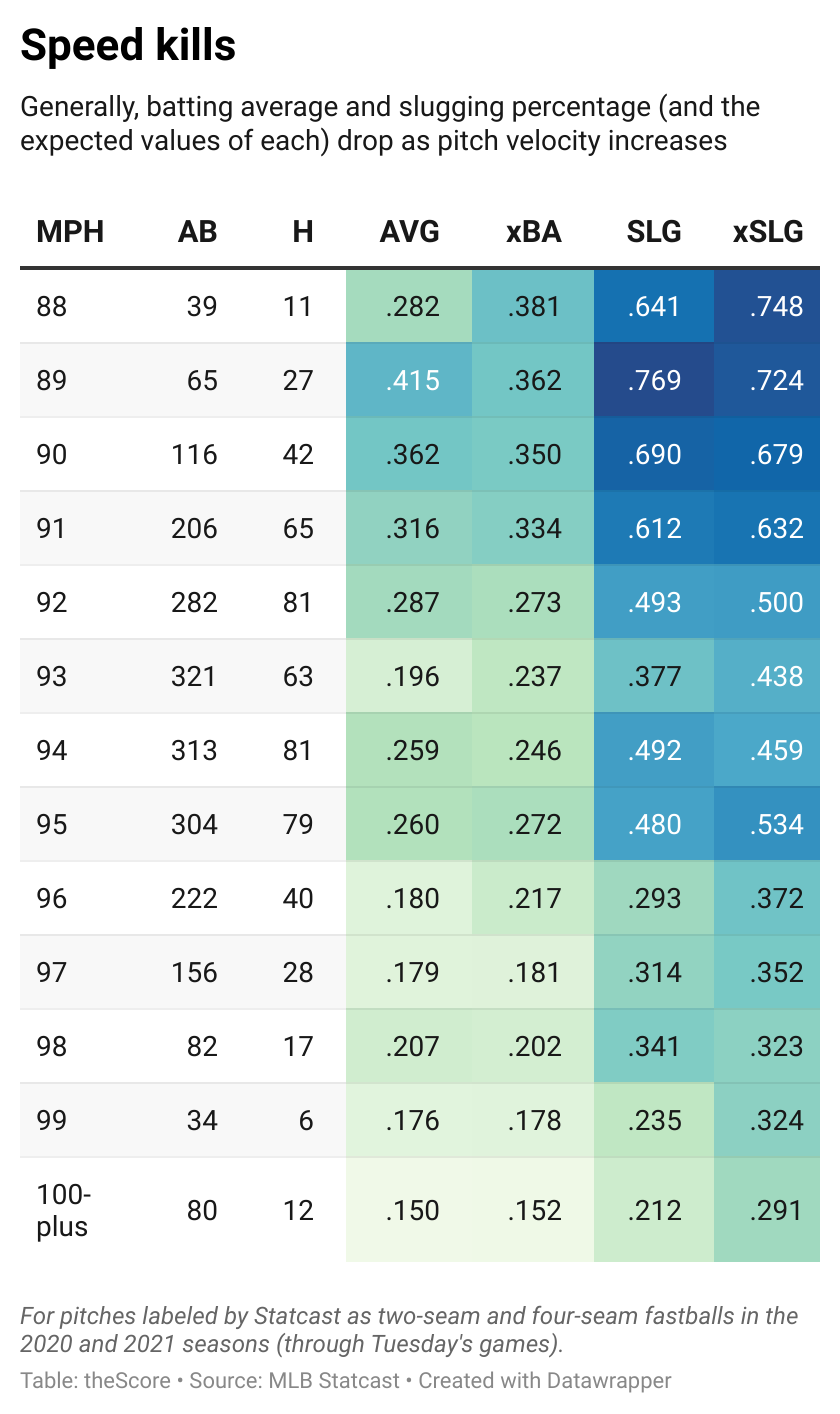

Baseball claims the change will make a 93.3 mph fastball from the standard distance the equivalent of a 91.6 mph fastball from 61.5 feet. During the pitch-tracking era, the average fastball has increased from 91.8 mph in 2008 to 93.5 last season.

The change that extra foot would provide would be significant.

Since the start of last season, MLB batters have an expected batting average of .237 against 93-mph two- and four-seamers, a .273 expected average against 92-mph fastballs, and a .334 expected average against 91-mph fastballs. Expected batting average uses exit velocity and launch angle to determine the likelihood of a batted ball becoming a hit based on past hits or outs with the same parameters. Expected slugging percentage jumped from .438 against 93-mph fastballs to .632 against 91-mph offerings.

I asked Rays starting pitcher Tyler Glasnow about the talk of moving the mound back last week, before the announcement of the experiment.

"I think that's the dumbest thing I have ever heard," said Glasnow, who was unaware of the 2020 experiment that was shelved. "I think there's obviously some logic in changing the game to try and keep up with the times, but it seems like it's all these shots out of left field. It seems like too much, too fast."

Glasnow noted pitchers have trained their entire careers to perform from one distance. To change the distance, he believes, would be unfair.

"One day to the next it changes? It seems people think it's easier than it really is," Glasnow said. "I think everyone should stop (messing) with the game. It's fine."

MLB's tried other measures.

It introduced a less lively ball this season - at least a ball that travels less distance on long fly balls - and released a memo to pitchers warning that it would be monitoring them to infer who might be doctoring the ball. It's an attempt to reduce spin rate, and by extension, strikeouts.

So far, those actions have done nothing to slow trends.

Strikeouts are up again. For the first time, a quarter of plate appearances are ending in strikeouts. And home runs continue to fly out of ballparks. The data and training tools to help players to achieve these outcomes had never been better. Thus, pitchers are incentivized to strike out batters, and batters are incentivized to hit home runs.

MLB has struggled to make the 2020s' game play like that of the 1980s or even the 2010s. Glasnow is a great example of that as the slider he's added with the help of a high-speed camera and spin-tracking technology has allowed him to reach another level early this season.

Entering play Wednesday, MLB batting average was .234, which would be the lowest on record dating back to the 19th century. The full-season record low is .237, set in 1968, which compelled baseball to lower the mound by five inches in 1969.

Batters slashed .237/.288/.340 in 1968 against pitchers standing 15 inches above the playing surface. In 1969, they slashed .248/.320/.369 when the mound was lowered to 10 inches.

However, baseball hasn't altered the mound distance since it did so several times in the late 19th century, according to research by MLB historian John Thorn.

"National League batting averages declined every year from 1877 to 1880, falling from .271 to an alarming .245. The number of strikeouts nearly tripled as pitchers perfected the curves and slants introduced only a decade before," Thorn wrote. "The league ERA was 2.37. The fledgling circuit, which in those years included franchises in such marginal sites as Troy, Syracuse, Worcester, and Providence, was losing money and in big trouble."

That situation sounds a bit familiar to baseball in 2021, though franchise values and MLB revenues are now in the billions.

"To the rescue came Harry Wright, the organizer of the Cincinnati Red Stockings and 'Father of Professional Baseball.' He perceived the threat as early as 1877 when, in the Red Stockings' final exhibition contest, he had the pitcher's box moved back 5 feet."

The mound would be moved back several times, finally to 60 feet, 6 inches, and a pitching rubber was added in 1893.

Glasnow said if he had to choose between lowering the mound or moving it back, he’d choose "neither."

Pressed on the issue, he made a choice between hypotheticals.

"If I had to choose one, I would say to lower the mound, but they already lowered the mound a long time ago," Glasnow said.

Rays pitching coach Kyle Snyder has his pitchers train off of various mound conditions. He said no mound is the same and by the time a reliever enters a game the mound is no longer 10 inches, with the surface having been compressed and altered to some degree, from landing spots to divots dug in front of the rubber.

"I'd rather push it back than lower it," Snyder said. "I think there is the potential to see more injuries. … This is just a theory of mine, but if we were to break the mound down another 5 inches, I think you would see a lot of earlier rotation due to a flatter arm and not getting an arm up."

In other words, that could cause injuries.

MLB said it studied biomechanics from a variety of mound distances, up to 63 feet, in a lab setting in 2019 and found no changes to those pitchers studied. But those were college arms not pitching in game conditions.

"There's been a lot of rule changes in my lifetime," Snyder said. "It's not going to stop. It's like technology and golf and the constant conversations they are having there."

The other rule, the "double hook," also targets pitchers: It's designed to keep them in the game. San Diego starter Blake Snell is probably all for this one.

In MLB's last full season in 2019, pitchers averaged 5.2 innings per start. Last season, that fell to 4.8 innings. Entering Tuesday, appearances averaged 5.0 innings. It's a far cry from the days when the game's best pitchers threw 300 innings in a year.

Since the start of 2019, 40% of all DH plate appearances have come after the fifth inning, including extra innings. Now, should the "double hook" be implemented, MLB teams may move their DH to different places in the batting order. For instance, the leadoff spot has had just 37% of its plate appearances occur in the sixth inning or later. Either way, a significant portion of plate appearances would be altered should pitchers keep exiting as early as they are.

The rule would certainly encourage teams to leave starting pitchers in games longer. But how aggressively will teams want to push pitchers in an era where injuries have generally been on the rise? Teams continue to make decisions guided by pitch counts and the "hook" rule might not be as much of a deterrent as the league hopes. Moreover, an independent minor league is probably going to value starting pitcher stress less stringently than a major-league club, which might have spent eight figures in salary on a prized arm for that season.

The experiments in the Atlantic League will not be a perfect comparison, but they'll be worth watching and examining as the inevitable march to more strikeouts and fewer balls in play continues this summer.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer. Follow him on Twitter at @Travis_Sawchik.